CHAPTER 4 THE RISK MANAGEMENT PROCESS

advertisement

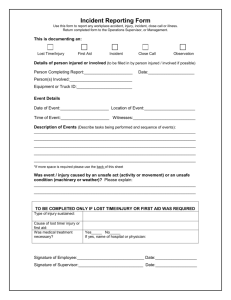

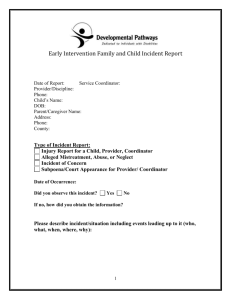

CHAPTER 4 THE RISK MANAGEMENT PROCESS TR-4-1 THE RISK MANAGEMENT PROCESS 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Determination of objectives Identification of risks Evaluation of risks Consideration of alternatives - selection of the tool Implementing the decision Evaluation and review TR-4-2 DETERMINATION OF OBJECTIVES The first step in the risk management process is the determination of the objectives of the risk management program. • Despite its importance, determining the objectives of the program is the step in the risk management process that is most likely to be overlooked. • Many of the defects in risk management programs stem from an ambiguity regarding the objectives of the program. MEHR AND HEDGES PRE-LOSS AND POST-LOSS OBJECTIVES TR-4-3 Mehr and Hedges suggest that risk management has a variety of objectives, which they classify as pre-loss objectives and post-loss objectives Post-Loss Objectives Pre-Loss Objectives Survival Continuity of operations Earning stability Continued growth Social responsibility Economy Reduction in anxiety Meeting externally imposed obligations Social responsibility TR-4-4 VALUE MAXIMIZATION OBJECTIVES Neil Doherty has argued that the ultimate goal of risk management is the same as that of other functions in a business—to maximize the value of the organization. • This is a view with which it is difficult to disagree and seems consistent with the objectives suggested by Mehr and Hedges. • The value maximization objective is relevant primarily to the business sector. For nonprofit organizations and government bodies it is not particularly meaningful. 137 THE PRIMARY OBJECTIVE OF RISK MANAGEMENT TR-4-5 The primary goal of risk management is not to contribute directly to the other goals of the organization—whatever they may be. • It is to guarantee that the attainment of these other goals will not be prevented by losses that might arise out of pure risks. • The primary objective of risk management—like the first law of nature—is survival. THE PRIMARY OBJECTIVE OF RISK MANAGEMENT TR-4-6 The primary objective of risk management is to preserve the operating effectiveness of the organization; that is, to guarantee that the organization is not prevented from achieving its other objectives by the losses that might arise out of pure risk. TR-4-7 RISK MANAGEMENT POLICY Major policy decisions related to pure risks should be made by the highest policy-making body in the organization—such as the Board of Directors. Once the objectives have been identified, they should be formally recognized in a formal risk management policy. A formal risk management policy statement provides a basic for achieving a logical and consistent program by providing guidance for those responsible for programming and buying the firm's insurance. RISK IDENTIFICATION IN HEALTH SERVICES ORGANIZATIONS Much as other organizations, HSO’s must establish mechanisms by which they can identify potential risks including near misses, actual loss-producing events, and risks that may lead to future losses. The early identification of organizational risks is important for a number of reasons: (1) Allows for prompt investigation while event(s) are most current and likely to be recalled with accuracy (2) Allows for consideration of early intervention(s) to reduce or eliminate the risk/loss (3) Allows for improved planning for risk financing/transfer (more accurate reserves establishment, litigation management, etc.) 138 SYSTEMS FOR RISK IDENTIFICATION IN HSO’s Such systems may be formal and/or informal. Formal systems for risk identification within HSO’s are established by organizational policies and procedures, typically as required pursuant to insurance contracting, accreditation guidelines, and/or regulatory statutes. Formal risk identification systems include the following: (1) Incident reporting (2) Sentinel event tracking (3) Occurrence reporting (4) Occurrence screening INCIDENT REPORTING SYSTEMS An incident is defined as any happening that is not consistent with the routine care of a particular patient or an event that is not consistent with the normal operations of a particular organization. The most useful output of incident reporting systems is the incident report. The contents and format of such reports will vary somewhat from HSO to HSO. The most common data elements included in an incident report includes: (1) Demographic Information – name, address, telephone number of affected person(s). Medical record number if patient involved. (2) Facility Information – Patient admission date/visit date, patient name/room number, admission diagnosis/principal complaint (3) Socio-Economic Information – age, gender, marital status of affected person(s), employment, insurance status. (4) Incident Description – Location of incident, type of incident (medication error, therapeutic error, diagnostic error, etc.), extent of patient/person injury, result(s) of physical examination, pertinent environmental findings. Though common to most larger HSO’s, the overall efficacy of incident reporting systems has been shown to be poor. Research by Berwick, for example, showed that voluntary incident reporting systems failed to identify t he large majority of “true” adverse events within a sample of hospitals. 139 The most commonly identified obstacles that inhibit the success of such systems include the following: (1) Time constraints on staff (lack of time to complete formal incident report) (2) Low perception of value among staff due to lack of RM feedback on outcomes of such reports (3) Staff fear of disciplinary action/lawsuit from such reporting (4) Staff fear/apprehension of reporting adverse events associated with MD activities (5) Staff failure to recognize a true incident (lack of understanding) In order to improve the efficacy of incident reporting as a risk identification device, most RM experts recommend increasing/improving staff education with regard to what a true incident is and why it’s important to report, and establishing detailed policies and procedures to facilitate / formalize such reporting. OCCURRENCE REPORTING / SCREENING A more active (mandatory) system of risk identification within HSO’s (true surveillance system), mandated by JCAHO. A number of adverse events / incidents are defined as “mandatory reports” via such systems by JCAHO (Exhibit 8-1 and 8-2): (1) Diagnosis occurrences ( missed diagnoses, misdiagnoses) (2) Surgical occurrences (wrong patient, wrong body part) (3) Therapeutic / procedure-related occurrences (4) Blood-related occurrences (5) IV-related occurrences (6) Medication-related occurrences (7) Falls (8) Other adverse events (nosocomial infections, decubitus) Occurrence screening involves the concurrent screening for potential adverse events / risk factors for adverse events. Traditionally considered a QA function, risk management makes use of such data, where available, for data trending of risk factors and root-cause studies. 140 INFORMAL RISK IDENTIFICATION SYSTEMS Committee meeting minutes (CQI, QA, safety, infection control, P&T) Historical insurance claims data (industry vs. HSO loss data for benchmarking) Accreditation survey reports (JCAHO, CARF, OSHA, etc.) Floor rounds with staff, patients, physicians, etc. CURRENT TRENDS IN INCIDENT / OCCURRENCE REPORTING/TRACKING The use of computerized systems of risk identification has become more and more commonplace within HSO’s. Increasingly, larger HSO’s have invested in the development of dedicated risk management information systems (RMIS), which are used to collect and analyze data on risk exposures and adverse events, including benchmarking analyses and the production of customized risk management reports. The compatibility of RMIS with other HSO information systems (financial, clinical) is critical. JCAHO SENTINEL EVENT REPORTING JCAHO developed and implemented a series of policies and procedures / guidelines for mandatory reporting of sentinel events effective 1/1/1999. A sentinel event is defined as any unexpected occurrence involving patient death or serious physical / psychological injury, or the risk thereof (i.e. any process variation for which a recurrence would carry a significant chance of a serious adverse outcome). JCAHO guidelines require the following to be reported / documented for all such events as defined: (1) Completion of a formal root cause analysis of the event (2) Development of a formal action plan to address the specific root causes of the event by implementing specific process changes to reduce / eliminate risk and monitor the effectiveness of such changes post hoc. Under current accreditation guidelines, JCAHO also encourages HSO’s to voluntarily self report sentinel events to JCAHO. At a minimum, all accredited HSO’s must provide JCAHO with the documentation of their root cause analysis results and action plan to address all sentinel events, whether self-reported to JCAHO or not. 141 TR-4-11 EVALUATING RISKS Evaluation implies some ranking in terms of importance, and ranking suggests measuring some aspect of the factors to be ranked. In the case of loss exposures, there are two facets that must be considered; • the possible severity of loss • the possible frequency or probability of loss A PRIORITY RANKING BASED ON SEVERITY TR-4-12 Criticality analysis attempts to distinguish truly important things from the overwhelming mass of unimportant things. • Certain risks, because of the severity of the possible loss, will demand attention prior to others. • In most instances there will be a number of exposures that are equally demanding. A PRIORITY RANKING BASED ON SEVERITY TR-4-13 Any exposure that involves a loss that would represent a financial catastrophe ranks in the same category, and there is no distinction among risks in this class. Rather than ranking exposures in some order of importance such as "1, 2, 3, ... etc.," it is more appropriate to rank them into general classifications: • Critical risks include all exposures to loss in which the possible losses are of a magnitude that would result in bankruptcy. • Important risks include those exposures in which the possible losses would not result in bankruptcy, but would require the firm to borrow in order to continue operations. • Unimportant risks include those exposures in which the possible losses could be met out of the existing assets or current income of the firm without imposing undue financial strain. A PRIORITY RANKING BASED ON SEVERITY TR-4-14 Assigning individual exposures to one of these categories requires determination of the amount of loss that might result from a given exposure and also requires determination of the ability of the firm to absorb such losses. Determining the ability to absorb the losses involves measuring the level of uninsured loss that could be borne without resorting to credit, and the determining the maximum credit capacity of the firm. TR-4-17 PROBABILITY AND PRIORITY RANKINGS Although the potential severity is the most important factor in ranking exposures, an estimate of the probability may also be useful in differentiating among exposures with relatively equal potential severity. 142 • Other things being equal, exposures characterized by high frequency should receive attention before exposures with a low frequency. • Exposures that exhibit a high loss frequency are often susceptible to improvement through risk control measures. TR-4-18 PROBABILITY AND PRIORITY RANKINGS Even broad generalizations about the likelihood of loss may be useful. One suggested approach is to classify probability as • almost nil (meaning that, in the opinion of the risk manager, the event is probably not going to happen), • slight (meaning that while the event is possible, it has not happened and is unlikely to occur in the future), • moderate, (meaning that the event has occasionally happened and will probably happen again), and • definite (meaning that the event has happened regularly in the past and is expected to occur regularly in the future). CONSIDERATION OF ALTERNATIVES AND SELECTION OF RISK TREATMENT DEVICE Once risks have been identified and measured, a decision must be made regarding what, if anything, should be done about each risk. TR-4-19 Several approaches have been suggestion as strategies for these decisions and some have proven more productive than others. DECISION THEORY AND RISK MANAGEMENT DECISIONS TR-4-21 The most appropriate approaches to risk management decisions are drawn from decision theory and operations research. The types of problems addressed by the decision theory approach to decisionmaking are those for which there is not an obvious solution, the situation that characterizes many risk management decisions. The decision theory approach aims at identifying the best decision or solution to the problem. TR-4-24 EXPECTED VALUE Decision theory suggests three classes of decision-making situations, based on the knowledge the decision-maker has about the possible outcomes. • Decision-making under certainty: the outcomes that result from each choice are known (and therefore cost-benefit analysis is appropriate). • Decision-making under risk: the outcomes are uncertain but probability estimates are available for the various outcomes. • Decision-making under uncertainty: the probability of occurrence of each outcome is not known. 143 TR-4-25 CRITERIA FOR DECISION-MAKING UNDER RISK In decision-making under risk, where the probability of different outcomes can be predicted with reasonable precision, expected values can be computed to determine the most promising choice. • A decision or choice is described in terms of a payoff matrix, a rectangular array whose rows represent alternative courses of action and whose columns represent the outcomes or states of nature. • The expected value for a particular decision is the sum of the weighted payoffs for that decision. The weight for each payoff is the probability that the payoff will occur. EXPECTED VALUE AS A CRITERIA FOR DECISION-MAKING UNDER RISK TR-4-27 In some situations, the expected value criterion that is used in decision-making under risk can be used as a strategy for risk management decisions, such as the choice between retention and the purchase of insurance. State 1 No Loss State 2 Loss Occurs Expected Value Insure –$1,500 X .99 –$1,500 X .01 $1,500 Retain $0 X .99 –$100,000 X .01 $1,000 Expected value is an appropriate strategy when the results will be repeated over a large number of trials. Expected value strategy will always suggest retention over insurance, due to the fact that actual cost of any insurance against any financial loss will always be more than the expected loss due to the presence of insurance loading charges. EXPECTED VALUE AND RISK MANAGEMENT STRATEGY TR-4-29 There are two problems with the expected value model for risk management decisions. • The first is that the expected value model requires that the decision-maker have accurate information on the probabilities, which is not available as often as desired. • Even when accurate probability estimates are available, actual experience may deviate from the expected value. • Although the long-run expected value of the retention strategy is -$1,000, a loss of $100,000 could occur. • If a $100,000 loss is unacceptable to management, the long-run expected value is irrelevant. 144 TR-4-30 PASCAL’S WAGER The defects in the expected value strategy suggested the need for a different strategy in some situations. Blaize Pascal, a Seventeenth Century mathematician considered the situation in which the probability of an outcome is not known, and in which there is a significant difference in the possible outcomes. The question about which Pascal was concerned was the existence of God. According to Pascal, one believes in God of one does not. There is no way to estimate the probability or likelihood that God exists. The decision, therefore, is not whether to believe in God, but rather whether to act as if God exists or does not exist. The choice, in Pascal’s view, is, in effect, a bet on whether or not God exists. • If one bets that God exists, he or she will lead a good life. • A person who leads an evil life is wagering that God does not exist. TR-4-32 PASCAL’S WAGER If God does not exist, whether you lead a good life or a bad one is immaterial. But suppose, says Pascal, that God does exist. • If you bet against the existence of God (by refusing to lead a good life) you lose and suffer eternal damnation • the winner of the bet that God exists has the possibility of salvation. • Because salvation is preferable to damnation, for Pascal the correct decision is to act as if God exists. TR-4-33 PASCAL’S WAGER Pascal’s Wager introduces two significant principles for decision-making. • There are some situations in which the consequence (magnitude of the potential loss) rather than the probability should be the first consideration. • These are situations in which one of the outcomes is so undesirable that its possibility is unacceptable. • Even when dependable probability estimates are not available, decisions made under conditions of uncertainty can be made on a rational basis. TR-4-34 MINIMAX REGRET STRATEGY In modern decision theory, the equivalent of Pascal’s strategy is known as minimax (standing for minimize maximum regret). 145 In the minimax regret strategy, the decision maker attempts to minimize the maximum loss or maximum regret. For problems such as those in risk management, in which costs are to be minimized, the maximum cost of each decision for each possible outcome is listed and the minimum of the maximums is selected as the appropriate choice, which gives rise to the term "minimax." TR-4-35 State 1 No Loss State 2 Loss Occurs Maximum Loss Insure –$1,500 –$1,500 –$1,500 Retain $0 –$100,000 –$100,000 TR-4-36 Minimax Regret is an appropriate strategy when the maximum cost associated with one of the outcomes is unacceptable to management. DECISION THEORY AND RISK MANAGEMENT DECISIONS TR-4-37 Note that the expected value strategy will always suggest retention over insurance. Note also that the minimax regret strategy will always suggest transfer (insurance) over retention. The question, then, is when is which strategy appropriate? The answer was suggested in three rules set forth in the first textbook on risk management (by Mehr & Hedges). TR-4-38 THE RULES OF RISK MANAGEMENT Don't Risk More Than You Can Afford to Lose Consider the Odds Don't Risk a Lot for a Little 146 RISK CHARACTERISTICS AS DETERMINANTS OF THE TOOL TR-4-39 TR-4-43 High Frequency Low Frequency High Severity Avoid Reduce Transfer Low Severity Retain Reduce Retain TR-4-44 THE SPECIAL CASE OF RISK REDUCTION 1. A technique or tool should be used when it is the lowest cost approach for the particular risk. 2. Humanitarian considerations and legal requirements sometimes dictate that risk control be used when it is not the lowest cost approach. 3. OSHA requires employers to incur expenses that might not be justified based on a marginal-revenue/marginal cost analysis. 4. Building codes impose similar mandates. TR-4-46 IMPLEMENTING THE DECISION Once the decision is made as to how a particular risk will be addressed, action must be taken to implement the decision. • Avoid • Reduce • Retain • Transfer TR-4-47 EVALUATION AND REVIEW Evaluation and review must be included in the program for two reasons. • Things change: new risks arise and old risks disappear. The techniques that were appropriate last year may not be the most advisable this year, and constant attention is required. • Mistakes are sometimes made. Evaluation and review of the risk management program permits the risk manager to review his decisions and discover his mistakes, hopefully before they become costly. 147 EVALUATION AND REVIEW AS MANAGERIAL CONTROL TR-4-49 The evaluation and review phase of the risk management process is the managerial control phase of the risk management process. Control requires: (1) setting standards or objectives to be achieved; (2) measuring performance against those standards and objectives; and (3) taking corrective action when results differ from the intended results. EVALUATION AND REVIEW AS MANAGERIAL CONTROL TR-4-50 A disastrous loss need not occur for performance to deviate from what is intended. Because risk management deals with decisions under conditions of uncertainty, adequate performance is measured not only by whether the organization survives, but whether it would have survived under a different set of circumstances. • The existence of an inadequately addressed exposure with catastrophic potential represents a deviation from the intended objective. • It is this type of deviation from objectives that the risk management control process is intended to address. QUANTITATIVE PERFORMANCE STANDARDS TR-4-51 Ideally, standards should be quantified whenever possible. • The cost of risk is the total expenditures for risk management, including insurance premiums paid and retained losses, expressed as a percentage of revenues. • Although the cost of risk may fluctuate because of factors over which the risk manager has no control, it is a useful standard when properly interpreted. QUANTITATIVE PERFORMANCE STANDARDS TR-4-52 Quantitative performance standards are more prevalent in the area of risk control than for risk financing functions. • Standard injury rates reflecting frequency and severity are available as benchmarks for measuring performance in the area of employee safety. • Similarly, motor vehicle accident rates and other frequency and severity rates are useful benchmarks in measuring risk control measures. TR-4-53 RISK MANAGEMENT AUDITS Although evaluation and review is an ongoing process, the risk management program should periodically be subjected to a comprehensive review called a risk management audit. 148 A risk management audit is a detailed and systematic review of a risk management program, designed to determine • if the objectives of the program are appropriate to the needs of the organization, • whether the measures designed to achieve the objectives are suitable, and • whether the measures have been properly implemented. TR-4-54 RISK MANAGEMENT AUDITS While risk management audits may be conducted by an external party, they may also be performed internally. The benefits of internal audits will be maximized to the extent that they are conducted—to the extent possible—in the same way as an external audit. 149