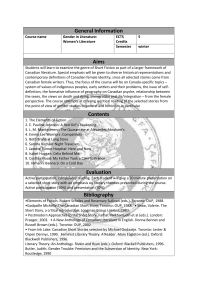

AFRICAN CANADIAN LEGAL CLINIC Canada's Forgotten Children

advertisement