WORKING PAPERS IN ECONOMICS & ECONOMETRICS The state

advertisement

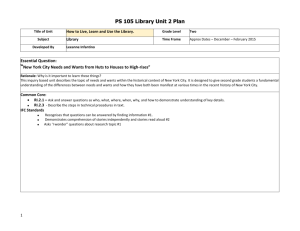

WORKING PAPERS IN ECONOMICS & ECONOMETRICS The state and scope of the economic history of developing regions Stefan Schirmer University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa Latika Chaudhary Scripps College, USA Metin Cosgel University of Connecticut, USA Jean-Luc Demonsant University of Guanajuato, Mexico Johan Fourie Stellenbosch University, South Africa Ewout Frankema Utrecht University, the Netherlands Giampaolo Garzarelli University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa John Luiz University of the Witwatersrand Business School, South Africa Martine Mariotti (Australian National University) Martine.mariotti@anu.edu.au Grietjie Verhoef University of Johannesburg, South Africa Se Yan Peking University, China JEL codes: N01 Working Paper No: 517 ISBN: 086031 517 6 April, 2010 The state and scope of the economic history of developing regions1 ş STEFAN SCHIRMER2, LATIKA CHAUDHARY3, METIN CO GEL4, JEAN‐LUC DEMONSANT5, JOHAN FOURIE6, EWOUT FRANKEMA7, GIAMPAOLO GARZARELLI8, JOHN LUIZ9, MARTINE MARIOTTI10, GRIETJIE VERHOEF11 AND SE YAN12 Abstract This paper examines the state and scope of the study of economic history of developing regions, underlining the importance of knowledge of history for economic development. While the quality of the existing research on developing countries is impressive, the proportion of published research focusing on these regions is low. The dominance of economic history research on the North American and Western European success stories suggests we need a forum for future research that contributes to our understanding of how institutions, path dependency, technological change and evolutionary processes shape economic growth in the developing parts of the world. Many valuable data sets and historical episodes relating to developing regions remain unexplored, and many interesting questions unanswered. This is exciting. Economic historians and other academics interested in the economic past have an opportunity to work to begin to unlock the complex reasons for differences in development, the factors behind economic disasters and the dynamics driving emerging success stories. Keywords: Africa, China, Cliometrics, developing countries, development, India, institutions, Latin America, Middle East, new economic history JEL: N01 1 Draft version. Prepared for the June 2010 issue of Economic History of Developing Regions. University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa 3 Scripps College, USA 4 University of Connecticut, USA 5 University of Guanajuato, Mexico 6 Stellenbosch University, South Africa 7 Utrecht University, the Netherlands 8 University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa 9 University of the Witwatersrand Business School, South Africa 10 Australian National University, Australia 11 University of Johannesburg, South Africa 12 Peking University, China 2 1 1. INTRODUCTION During the past 50 years important developments in Economic History have enhanced our understanding of the role institutions, path dependency, technological innovation and evolutionary processes play in determining economic growth. This intellectual endeavour has mostly focussed on the economic histories of developed countries and regions. The studies of developing regions that have been undertaken have played a major role in furthering our understanding of the longevity of institutions, the importance of trade and education for growth, and the social and economic consequences of colonialism. Yet, despite this contribution, the proportion of articles focused on developing countries remains low. On average, less than 20% of all submissions between 2004 and 2008 to the Journal of Economic History have been on topics outside Western Europe, the United States and Australia/New Zealand. The same is true for related journals.1 Table 1: Submission topics by region to the Journal of Economic History 2004‐ 2005‐ 2006‐ 2007‐ 2005 2006 2007 2008 Africa 2 3 1 1 Asia 16 7 12 17 Australia and New Zealand 2 3 2 2 Eastern Europe 3 2 4 7 Great Britain 20 14 16 12 Latin America 5 7 9 9 Middle East 5 5 2 6 Non‐Spanish speaking Caribbean 0 0 0 0 United States 65 57 38 72 Western Europe 37 38 44 43 Not applicable 6 5 5 9 Developing regions 31 24 28 40 Total 161 141 133 178 Percentage 19.3% 17.0% 21.1% 22.5% Source: Hoffman and Fishback (2009) During the past decade major articles and books on Latin America, Asia, Africa and the Middle East have been written by leading scholars (Pomeranz 2000; Sokoloff and Engerman 2000; Acemoglu, Johnson et al. 2001; Acemoglu, Johnson et al. 2002). Their focus has largely been on explaining the differences between Europe and North America on the one hand and specific developing regions on the other. These are, it must be said, extremely valuable contributions that have stimulated fruitful debates and energised the study of economic history. It is, furthermore, equally encouraging that there is an increasing flow of work coming out of the leading universities that use history to enhance our understanding of the development process (La Porta et al. 2008; Nunn 2008; Dell 2010). The emergence of rich 1 Of the 29 papers published in 2009 by Elsevier’s Explorations in Economic History, only five dealt with topics outside Europe, the U.S. and Japan, four of them in a special edition on heights and human welfare. The proportions are similar for the Journal of Economic History, published by Cambridge University, with only six of the 32 papers published in 2009 covering topics on developing regions, and for the Economic History Review, published by Wiley-Blackwell, seven papers of the 37 published. 2 data sets and the digitalization of these, the pervasive presence of English as academic lingua franca, combined with more research graduates from developing countries at the top Western institutions specialising in economic history have brought to light a vast new research field formerly restricted to isolated departments of history and development studies. The search for natural experiments in history – the economist’s laboratory – has also redirected the attention of established scholars to such episodes in the developing world (Diamond and Robinson 2010). The outcome of all this is that the economic history of developing regions is taking off. At the same time, major shifts are taking place in the methods used to analyse the economic past. In a useful summary Nunn (2009) points out that rather than simply relying on (possibly spurious) correlations between historical events and present‐day outcomes, better estimation techniques and richer data sets have allowed a shift towards better identification of the mechanisms by which historical events shape future outcomes.2 Nunn (2009) predicts that future work in economic history will become more confined and specific in scope, using micro‐data to identify ‘finer causal factors and more precise mechanisms’. This implies a reemergence of historical enquiry into each growth episode. The Economic History of Developing Regions aims to encourage this trend. Besides the more familiar cliometric approach, another, younger method for neatly designed micro and comparative studies is the analytic narrative (Bates et al. 1998). As the name implies, the analytic narrative combines the traditional historical account or story with rational choice reasoning. In its simplest manifestation the analytic narrative may be formal but not highly rigorous: it may simply combine the economic logic of calculation at the margin with historical narration. In its more rigorous manifestation, the analytic narrative employs formal modelling, particularly game theory, to historical narration. The couching of the particular historical episode in terms of the more general logic of the economic actor is the quintessence of the analytic narrative. The Economic History of Developing Regions also welcomes the formal and rigorous analytic narrative approach to economic history as it welcomes the cliometric one. As economic history research tends to become more specialised, there is also a growing need for studies that tie the results of increasingly diversified strands of research together. Certainly, many economic history journals claim to focus on such overarching questions as to why some countries and regions have grown rich, while other stayed poor. But substituting a South‐South perspective for the conventional North‐South perspective will lead to new insights. It will stimulate scholarly debate and, ultimately, improve our explanation of the determinants of wealth and poverty. By offering a new forum for neatly designed micro‐studies as well as broader comparative studies on the economic history of developing regions, we aim to address the skewed spatial distribution of economic historical research, and to stimulate the search for deeper insights into the determinants of growth and development. The ever increasing number of scholars working on developing regions will result in an increased demand for publication space. Economic History of Developing Regions builds on the proud 24 year history of the South African Journal of Economic History which it replaces. The latter has played a significant role in keeping the study of economic history alive both in 2 Interestingly, nearly all the papers cited by Nunn (2009) dealing with the economic history of developing regions have been submitted or published in economics journals and not economic history journals. 3 South Africa and the African continent. It made seminal contributions in a number of areas. However, globalisation has increasingly meant that we need to look beyond our own immediate borders and to examine how we fit into the complex puzzle of developing countries. The lack of a journal specialising in the economic history of developing regions spurred us to action and we look forward to seeing, amongst others, comparative studies which explore intra‐ and interregional similarities and differences and contribute more broadly to our understanding of development in a historical context. It is our hope that Economic History of Developing Regions will become a forum for high quality economic history research and, ultimately, a leading journal in the field of economic history. 2. THE ECONOMIC HISTORY OF DEVELOPING REGIONS In a recent rallying call, Hopkins (2009) petitions historians to ‘re‐engage … in the study of Africa’s economic past not least because it is relevant to Africa’s future’. This statement is not only true for Africa but for all developing regions of the world. Understanding the process of economic change is necessarily linked to the past. Thus, exploring the economic history of the developing world must shed light on the causes of stagnation, and speed along the process of development. As noted above, the existing research on developing countries’ economic histories has already been informative. This section highlights some of those contributions. 2.1 Africa Despite enjoying a period of vibrancy stretching from the 1960s to the 1980s (Hopkins 1973), African economic history has, with a few notable exceptions (Austin 2005; Austin 2008) gone into decline. According to Hopkins (2009:157), ‘it is now more than twenty years since [economic] historians themselves produced big arguments attempting to understand Africa’s long‐run economic development and continuing poverty’. But a revival has been stimulated by leading economists. Although the 1990s economic growth literature ventured to explain Africa’s underperformance, Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson’s (AJR) seminal contribution at the start of the new millennium set a new research agenda that economic historians of Africa are beginning to embrace (Acemoglu et al. 2001; Acemoglu et al. 2002). They argue that colonies with a less deadly disease environment attracted greater European settlement which facilitated growth promoting institutions, namely, property right‐protecting ones. Where European mortality was high (and settlement low), colonisers established extractive rent‐seeking institutions that were detrimental to development. The empirical instrumental variables (IV) technique the authors use first estimates a strong negative relationship between initial settler mortality and institutional quality today and, in the second stage, finds that domestic institutions exert a strong positive effect on per capita income. The AJR contribution ignited interest in explaining the impact of African colonial history on current performance, exploiting newly available data. Nathan Nunn’s (2008; 2010) contribution to the new African economic history combines data from historic shipping records and constructs estimates of the number of slaves shipped during four African slave trades: the trans‐Atlantic, Indian Ocean, Red Sea and trans‐Saharan. He finds that those areas from which the largest numbers of slaves were taken are today the poorest regions in Africa. Nunn and Wantchekon (2009) extends this to a theory of mistrust, postulating that the impact of the slave trade works through factors that are internal to the individual, such as cultural norms, beliefs, and values . The slave trade also resulted in Africans moving into 4 areas that were more rugged, putting large numbers of people in areas with low growth potential (Nunn and Puga 2009). Bolt and Bezemer (2009) use data on colonial human capital and find a strong link with long‐run growth. They argue that education explains growth better and shows greater stability over time than do the measures of extractive institutions posited by AJR, and that the impact of settler mortality is through education rather than institutions. Using household surveys from the 1990s, Huillery (2009) finds a positive relationship between early colonial investments in education, health and infrastructure on current levels of schooling, health outcomes, and access to electricity, water, and fuel at the district level. Her detailed microdata also allows for advanced estimation techniques to determine the differences in outcome of neighbouring regions only, thus keeping all other variables constant. More examples of a combination of African archival records and modern estimation techniques that provide new insights, are now beginning to emerge (Buelens and Marysse 2009; Fafchamps and Moradi 2009; Moradi 2009; Nunn 2009; Fenske 2010). Other economic historians have criticised some of these new approaches. Austin (2008), for example, has been critical of the ‘reversal of fortune’ thesis because of insensitivity to diversity and context and for the compression of history. Although Hopkins acknowledges that AJR have been instrumental in “reopening lines of enquiry that are important for understanding both precolonial and colonial history” (Hopkins 2009:177), he shares Austin’s concerns. Hopkins is correct in questioning the ‘sweeping’ or ‘broad brush’ collating effect of the early econometricians’ methodology in researching the economic history of Africa. Hopkins suggests that research needs to “…proceed cautiously on a case‐ by‐case basis and abandon the attempt to formulate one prescription for a large and diverse continent.” The use of both quantitative and qualitative microdata in region‐specific settings and more recent techniques of identification and falsification are increasingly used by both economists and historians (Fedderke and Schirmer 2006; Green 2009; Mariotti 2009; Boshoff and Fourie 2010; Fourie and von Fintel 2010). Such region‐specific case studies pave the way for further interdisciplinary collaboration which is essential in broadening our understanding of Africa’s economic past, present and future. 2.2 China In recent years there has been great interest among economists and historians in the long‐ run development of China. Much of this interest can be traced back to a very famous question raised by a renowned British sinologist Joseph Needham, known as “The Needham Question”: Why did the West overtake China in science and technology, despite the latter’s early successes? Economic historians have extended this question: why did the industrial revolution take place in Britain instead of China? Elvin (1973) and a few prominent scholars propose a demand side explanation to this question, arguing that one major factor preventing China from advancing as an industrialised economy was a high labour‐to‐land ratio limiting the incentive to invent new technologies in ancient China. In comparison, Lin (1995) attributes ancient China’s technological stagnation to the supply‐side. He argues that the long‐standing Imperial Civil Service Examination system in ancient China was the main channel through which bureaucratic officials were selected in a fair and impartial way. However, because the civil service examination system focused only on Confucianism and literary skills, most talented Chinese were fully devoted to either this examination or research of the humanities and lacked the incentives to accumulate knowledge in science. As a result, a scientific revolution was unlikely to spontaneously take place in China, even though China had satisfied many of the accepted crucial conditions for industrialisation as early as the twelfth century. 5 Although the explanations of China’s failure to industrialise are completely different, these studies share the same view: they attribute this divergence to some unique features in ancient Chinese society that made China intrinsically different from Europe. Philip Huang and quite a few traditional Chinese historians and demographers further advance this “pessimistic” view and argue that the Chinese economy was weighed down by overpopulation, and that a process Huang terms “involution”, resembling what others might characterise as a Malthusian trap, which prevented China from realising any progress in economic growth well into the 20th century. Since the end of the last century, this assessment has been challenged by Ken Pomeranz, R. Bin Wong, James Lee, and others, who have argued that China was doing much better than has been appreciated, especially in coastal areas, rivaling Europe in per capita income as late as the end of the 18th century. This more sanguine outlook, based on detailed (if also controversial) comparisons of China and Europe, suggests that conditions in pre‐modern China were much more favorable, both as regards living standards and prospects for sustained growth, than scholars had previously thought. This group of economic historians, many of whom are affiliated with the University of California (and thus usually categorised as the California school), believes that there were essentially no such China‐specific factors that made ancient China “inferior” to Britain or Europe. For example, Pomeranz (2000) attributes the divergence between Europe and China to the role of “geographic accidents” such as the proximity of coal deposits to early British centers of industrial production and the easily exploitable natural resources of the Americas. Their studies overthrow the ingrained Eurocentric growth model and have also been espoused by prominent European economic historians such as Jared Diamond, Greg Clark and Robert Allen (Diamond 1997; Clark 2008; Allen 2009; Clark and Cummins 2009; Allen et al. 2010). The California school has inspired more scholars to increasingly adopt the methodology of “horizontal” research, which frames the experience in China from the perspective of world economic history. They construct gauges of economic performance, such as output, real income and productivity, for regions of China and base comparisons between regions, and especially between them and regions or countries of Europe. Moreover, the traditional view that China was stagnating has not been subjected to much in the way of systematic empirical tests, either for the pre‐modern or modern periods. A scarcity of data has long plagued scholars of China, and prevented them from constructing a reliable record of Chinese economic development over the long run. With the recent movement toward the opening of archives in China, and the greater ease of collecting information made possible by advances in the power and portability of computers and scanners, the opportunities for scholars have expanded enormously. Carol H. Shiue, Debin Ma and Se Yan are three scholars who have conducted excellent research by combining economic theory and econometric methods with original data sets collected from Chinese historical archives. Trade expansion and market development have long been considered preconditions for industrial revolutions and sustainable economic growth. Therefore, examining development of the market in pre‐modern China would shed light on the causes of China’s failure to industrialise. Shiue (2002) uses regional grain price data collected by the Qing government, combined with historical weather data, to study the inter‐regional correlations of grain prices, which is used as an indicator of market integration. She finds that the overall level of market integration in China was higher than previously thought and that those inter‐ temporal effects are important substitutes for trade. Both factors reduce the importance of trade as a unique explanation for subsequent growth. More recently, Shiue and Keller 6 (2007) compare market integration in Europe and China on the eve of the Industrial Revolution, finding little difference, although somewhat better performance in England than in the Yangzi Delta. Debin Ma has assembled wage data of various types of laborers in different regions of China and, with historical price data, estimates the real income of these people from the eighteenth to the twentieth century (Ma 2008). The data are used to compare the standard of living in major Chinese cities to their counterparts in Europe, India, and Japan. Ma and his co‐authors (Allen et al. 2010) find that in the eighteenth century, the real income of building workers in Asia was similar to that of workers in the backward parts of Europe and far behind that of workers in the leading economies in northwestern Europe. Industrialisation led to rising real wages in Europe and Japan. Real wages declined in China in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and rose slowly in the late nineteenth and early twentieth. The income disparities of the early twentieth century were due to long‐run stagnation in China combined with economic development in Japan and Europe. The painstaking efforts made by Shiue, Ma and other economic historians to collect data for pre‐modern China are paving the way for a deeper understanding of China’s economic performances in that era. Studying pre‐modern China is crucial for a better understanding of the Great Divergence. However, the study of the economic developments of modern China (1842‐1949) is equally interesting. Until the 1840s, China was largely a closed, agrarian economy; however, pressure from Great Britain and other foreign powers led China to open its economy to international trade and later to foreign direct investment. Although the scarcity of data makes it virtually impossible to construct annual time series of GDP or other major economic indicators, scholars, such as John Chang, Ta‐chung Liu, and Thomas Rawski, have compiled various estimates of the speed and magnitude of industrial expansion and economic growth (Brandt and Rawski 2008). While this view of China’s accelerating economic change is shared by many historians and economists, its impact on people’s real income and standard of living has been poorly measured. In his doctoral dissertation, Se Yan (2008) compiles the first systematic evidence of patterns in real wages and living costs for China from 1858 to 1936. He constructs nominal wage series from the records of employees in the China Maritime Customs (CMC) service for nearly fifty Chinese cities. He also constructs group‐specific cost of living indices from price data and household budget information contained in CMC trade statistics and surveys. With these new nominal wage series and cost of living indices, Yan estimates the long‐run trends in real wages and in the ratios of wages for the skilled to unskilled workers and for highly skilled to unskilled workers. He finds that the skill premium rose rapidly during the first three decades of industrialisation, but began to level off and decline from the mid 1910s. Yan (2008) and Mitchener and Yan (2010) further find evidence suggesting that the reversal of the skill premium is possibly driven by two factors. First, the trade boom in China during the early twentieth century benefited unskilled workers relative to skilled. Second, educational progress increased the supply of skilled workers, thereby reducing the skilled wage. Of course, this cannot be a complete introduction of recent academic studies in this field. Many outstanding researchers have contributed to the progress in Chinese economic history. A more recent example is Zelin’s book, the Merchants of Zigong (2005), which has received much scholarly attention. All these concerted efforts have made China one of the most vibrant areas for the study of economic history. 7 2.3 India Over the last decade, the Indian colonial experience has entered broader conversations within the economics literature on the “Great Divergence”, the relationship between colonialism and institutional development, and the persistence of institutions. Furthermore, Indian economic history has embraced cliometrics. Researchers have constructed new district‐level datasets on railroad penetration (Donaldson 2008), educational spending (Chaudhary 2010) and communal violence (Jha 2008) to name a few examples. Economic theorists have used the East India Company operations to better understand the nature of contract enforcement (Hejeebu 2005) and the microeconomics of exports (Kranton and Swamy 2008). By adopting the cliometrics approach, Indian economic history has enhanced the ability to answer specific questions about the Indian context and general questions of interest to other economists. We focus here on a few recent studies and their implications for colonial rule in India. This is far from a comprehensive overview, but rather a description of recent advances. For a detailed overview, we recommend the reader to the Cambridge Economic History of India (Kumar 1983) and Roy (2000; 2002; 2004). While older studies suggest the divergence in economic development between Europe and Asia began only after the 19th century (Parthasarathi 1998; Pomeranz 2000), recent studies drawing on Indian wages, incomes and market integration find evidence of diverging standards of living well before 1800 (Broadberry and Gupta 2006; Studer 2008; Roy 2010). A stronger understanding of when India fell behind has important implications for how we view the colonial experience. If India was diverging from Europe in the early modern period, colonialism alone cannot be held accountable for the slow pace of Indian development in the 19th and 20th century. Several recent micro‐studies of individual sectors of the Indian economy also support a nuanced reading of colonial policies and their effects on the economy. For example, education spending under the Raj was low relative to other countries at comparable levels of development and the Indian Princely States. But, local factors such as a high degree of social heterogeneity and a strong preference for secondary education among Indian elites were important barriers to the spread of mass primary education (Chaudhary 2009). A study of late 18th century Bengal finds remarkable stability in income per‐capita in spite of the transition to colonial rule (Roy 2010). However, another novel study finds large and persistent effects of colonial land tenure systems on post‐independence agricultural productivity (Banerjee and Iyer 2005). Within infrastructure, the study of railways has enjoyed a recent resurgence. According to Andrabi and Kuehlwein (2010) railways had limited effects on price convergence between districts, but Donaldson (2008) finds large and positive effects of railways on price convergence and agricultural incomes using a sophisticated model and an original dataset from 1861 to 1930. Moreover, railways also appear to have reduced the severity of famines in colonial India (Burgess and Donaldson 2010). On the industrial organisation side, government ownership of Indian railways lead to significant productivity gains unlike other countries where efficiency declined following nationalisation (Bogart and Chaudhary 2010). The consequences of colonial policies, thus, range from no effects as in the case of 18th century Bengal to positive effects in the case of railroads. Given the diverse findings, we need more research studying the effects of colonial rule disaggregated by region, sector and time period. How did specific policies interact with local conditions? Why did colonial 8 policies succeed in some places and in some time periods? Why were some policies a complete failure? Can we attribute the negative effects to an extractive colonial state? Or, was colonial rule constrained by local factors? Detailed micro‐studies are essential to answering such questions and assessing the net macro effect of colonial rule in India. 2.4 Latin America The lion’s share of recent economic historical research on Latin America revolves around two closely interconnected questions. First, what explains Latin America’s growth retardation as compared to the West and, to a lesser degree, East Asia? Second, why is national income so unequally distributed in the majority of Latin American and Caribbean countries? With the exception of Haiti and Nicaragua all Latin American countries are nowadays classified as middle‐income countries, which basically means that these countries have sufficient ability to eradicate poverty entirely. Still, about one quarter of the region’s population lives at, or even under, the World Bank’s definition of the poverty line (Frankema 2009). Indeed, many of the scholarly debates that have emerged in recent years are in search of explanations of this peculiar feature of Latin American development (Bulmer‐Thomas et al. 2006). Adopting a very long term perspective, the conventional view is that policies of social repression, resource extraction and trade monopolisation have generated various forms of social, economic and political inequality that have hampered the development of markets and political order far into the post‐independence era. Catholicism, Caudillismo and the authoritarian nature of Iberian colonial rule have often been contrasted with the principles of cooperative government, free trade and Protestantism to explain the increasing income gap with the former British possessions in North America (Landes 1998; North et al. 2000). Engerman and Sokoloff (2000) have argued that the origins of institutional divergence are related to exogenous conditions such as Latin America’s population heterogeneity and natural resource abundance, rather than Iberian institutions and culture per se. Yet, an even newer strand of literature goes further, by arguing that Spanish institutions may have been different, but not necessarily inefficient or ‘bad’ for long term economic development (Elliot 2006). The presumed ‘absolutism’ of the Spanish Crown and the ‘myth of relentless extraction’ is contested on the basis of new empirical evidence revealing extensive fiscal bargaining procedures and a sophisticated system of imperial revenue transfers, which allocated collective goods across the Spanish American empire, while outright confiscation was limited. Effective fiscal institutions, so it is argued, do a much better job of explaining why the Spanish American empire ultimately proved to be more viable than the British American empire, (Marichal 2007; Irigoin and Grafe 2008). This debate intertwines with recent studies questioning the widely‐held belief that Latin American inequality has been persistent from colonial times onwards. A number of recent studies have shown impressive changes in wage differentials, wage‐rental ratio’s, labour income shares as well as Gini and Theil‐coefficients of income distribution over the past two centuries (Williamson 1998; Arroyo Abad 2008; Bértola et al. 2008). In view of this new evidence several scholars have argued that fluctuations in Latin American inequality have been driven by a combination of path dependent conditions and new, time‐specific determinants, which are not necessarily rooted in colonial history, nor ossified in the region’s future (Prados de la Escosura 2005; Frankema 2009). Moreover, some recent backward extensions of real wage and income distribution studies into the colonial era do not produce immediate evidence for extraordinary low living standards, nor for 9 exceptionally high levels of inequality (Milanovic et al. 2008; Dobado and Garcia 2009). Because most of the empirical picture still has to be reconstructed , this line of research is likely to continue for many years to come (Coatsworth 2008; Edwards 2009; Williamson 2009). A third debate even more directly connects the past with the present by addressing the effects of globalisation. Although the study of globalisation ‐ more narrowly defined as global or Atlantic market integration (and disintegration)‐ has a strong tradition in the famous Dependencia school, these recent studies are embedded in modern trade theory and largely neglect the once so influential Prebish‐Singer hypothesis (Prebish 1962). How do the causes, characteristics and consequences of the first wave of globalisation during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century compare to those of the current wave of globalisation that has emerged after the breakdown of import‐substitution policies? (Taylor 2006; Arroyo Abad and Santos‐Paulino 2009). The first wave seems to have spurred growth and inequality, but what about the second wave? What are the chances of a repeated resource curse? And does it matter that the former Atlantic market has now become a global market, including the new Asian giants? In the meantime, current rates of catch‐up growth in Brazil and the impressive pace of democratisation in Chile, indicate that the socio‐economic and political outlook of Latin America changes very rapidly. If this pace of change continuous and spills‐over to an increasing number of LACs, there is a good chance that these questions and interpretations soon have to be reformulated in order to keep up with recent developments. 2.5 The Middle East The economic history of the Middle East has recently experienced significant growth in both the volume and scope of scholarship. Until the late twentieth century, research on this region had been hampered by numerous obstacles, including linguistic barriers, government censorship, restrictions on access to archival resources, and lack of external demand and institutional support. Undeterred by these obstacles, prominent historians such as Gabriel Baer, Ömer Lütfi Barkan, Charles Issawi, Halil İnalcık, and André Raymond pioneered pathbreaking research programs, but progress in the field was slow and lagging behind that of other parts of the world. As these obstacles gradually waned and some of the significant historical questions of the Middle East and the Islamic world gained widespread attention, scholarship on the region has improved tremendously. The first decade of the twenty first century has witnessed the rise of economic history of the Middle East to a mature subfield, research being marked by the creative utilisation of primary sources, innovative application of sophisticated tools of quantitative analysis, and skilful employment of the recent methodological and theoretical developments in modern economics. As archival material has become more available and researchers have mastered innovative ways of using the available data, a proliferation of quantitative studies has taken place. Continuing a long established line of research, some historians have focused on specific regions and assembled information from various sources to identify how the resource profile, production patterns, size and composition of the population, and general economic outlook of the region has changed over time. These studies have typically used Ottoman tax registers as primary sources (Coşgel 2004). Other researchers have completed large gaps in our knowledge of how the Middle Eastern economies have performed in comparison with other parts of the world, providing reliable estimates of such macroeconomic indicators 10 (measured in standard units to facilitate comparisons) as money, prices, incomes, agricultural productivity, and anthropometric measures (Pamuk 2000; Özmucur and Pamuk 2002; Coşgel 2007 ; Stegl and Baten 2009). Another recent line of research has been to use data for not just estimating regional variables but for quantitative analysis of larger economic and historical questions, such as how risks and transaction‐costs shaped public finance and how military activities of the Ottomans affected intra‐European feuds (Coşgel and Miceli. 2005; İyigün 2008). Borrowing insights from new theoretical developments in modern economics, researchers have also brought new light to some of the longstanding puzzles of the region's history and introduced new questions invoked by these developments. For example, adopting a New Institutional approach and comparing Western and Middle Eastern institutions, they have identified the reasons why the Middle East adopted distinct institutional arrangements from the West and how the institutional rigidities of the Islamic Middle East have caused the economic underdevelopment of the region (Kuran 2004; Balla and Johnson 2009; Rubin 2010). Similarly applying developments in the political economy literature, they have studied where dictatorial rulers have obtained political power and how their search for legitimacy through agents has affected their choice of technology (Coşgel et al. 2009a; Coşgel et al. 2009b). Judging by recent trends in this field, future contributions to the economic history of the Middle East will most likely continue as increasingly more creative and sophisticated utilisation of primary sources, economic theory, and quantitative analysis. 3. CONCLUSIONS The regional accounts of economic historical research provided in the previous section are certainly not meant to be exhaustive. They are rather intended to motivate the potential value added of this new journal. Indeed, these short surveys suffice to derive a considerable number of common themes which are particularly suitable for exploration from a South‐ South perspective. These themes are central to the long term economic development of developing regions, but much less so to the development of the industrialised North. First of all, the term ‘developing region’ embodies the idea that economic growth and development has been hampered in the past, although it gives no clue as to the extent of underdevelopment. Unsurprisingly, section 2 points out that explaining the determinants of growth retardation is a central topic in the economic history literature of all these areas. There are some more specific issues involved when we start comparing the various developing regions’ growth trajectories. The twentieth century development paths have diverged enormously across the developing world, much more so than across the developed world. Comparative studies focusing on developing regions can greatly benefit from the wealth of variation in growth and development experiences, without running into the problem of comparing different development paths in different historical periods. The observation of diverging growth trajectories further begs the question when a region (or country) actually ceases to be a ‘developing region’. Economic History of Developing Regions offers a fruitful comparative framework to address this important question. Secondly, and directly related to the above, is the notion that developing regions have faced (and are facing) fundamentally different global economic and political conditions than the early industrialising nations were facing two centuries ago. It is probably fair to say that globalisation has a much deeper impact on both the economic constraints as well as the economic opportunities of developing regions. And it is not just a matter of being tied into 11 the global economy in a more encompassing way; developing regions also deal with the rather ‘exogenous force’ of an industrialised part of the world which exerts economic and military supremacy (at least until the end of the twentieth century). Whereas the research on the economic history of developing regions naturally takes this region and time‐specific global context into account, conventional studies on the developed world often takes this context for granted. The economic history of colonialism offers a rather specific, but by no means unimportant, example. As the accounts in section 2 point out, the perceived nature and consequences of former colonial rule play a central role in the economic history literature of Latin America, Africa, India and the Middle East. A similar conclusion applies to East and South East Asia (Booth 2007). And although China has never been a formal colony, its economic history has undoubtedly been shaped by foreign influences as well. But it matters a great deal whether discussions about colonial legacies are dictated by a metropolitan point of view (e.g. did empire place a burden on British taxpayers?) or by a local, developing region, point of view (e.g. what were the consequences of British fiscal policies for African state formation?). Finally, and again related to the above, is the question to what extent the historical process of market development in the North really set(s) a blueprint for market development in the developing regions. To the extent it does, all historical comparisons and reflections including the North are fruitful. To the extent that it does not, a South‐South perspective can fill an important gap. Many of the institutions guiding the long term evolution of factor and commodity markets are embedded in local history and culture. Some of these institutions may be ineffective because they do not reflect supposedly growth‐promoting values such as democracy, liberalism or individualism. But they may also be effective precisely because they are well‐embedded in local tradition. Economic history research still has a long way to go to disentangle the relationship between institutions and growth in developing regions and the aim of this new journal is to contribute to that objective. While the quality of the existing research on developing countries is impressive, the proportion of published research focusing on these regions is low.. The dominance of economic history research on the Northern ‘success stories’ suggests we need a forum for future research that contributes to our understanding of the way institutions, path dependency, technological change and evolution shape economic growth in the developing parts of the world. Many valuable data sets relating to developing regions remain unexplored, and many interesting questions unanswered. This is exciting. Economists, historians and other academics interested in the economic past have an opportunity to work to begin to unlock the complex reasons for differences in development, the factors behind economic disasters and the dynamics driving emerging success stories. We hope that Economic History of Developing Regions will help nurture a new generation of economic historians to show how the economic history of the developing countries can add to our understanding of economic theories, and, by learning from the lessons of the past, contribute to improving the state of many of the world's poorest economies. 12 4. REFERENCES Acemoglu, D., S. Johnson, and J. Robinson (2001). "The colonial origins of comparative development: an empirical investigation." American Economic Review 91: 1369-1401. Acemoglu, D., S. Johnson and J. Robinson (2002). "Reversal of Fortune: Geography and Institutions in the Making of the Modern World Income Distribution." Quarterly Journal of Economics 117(4): 1231-94. Allen, R., J.-P. Bassino, D. Ma, C. Moll-Murata and J-L. van Zanden (2010). "Wages, Prices, and Living Standards in China,1738-1925: in comparison with Europe, Japan, and India." Economic History Review forthcoming. Allen, R. C. (2009). "Agricultural productivity and rural incomes in England and the Yangtze Delta, c.1620-c.1820." Economic History Review 62(3): 525-550. Andrabi, T. and M. Kuehlwein (2010). "Railways and Price Convergence in British India." Journal of Economic History forthcoming. Arroyo Abad, A. L. (2008). Inequality in Republican Latin America: Assessing the Effects of Factor Endowments and Trade. GPIH Working Papers no. 12. Arroyo Abad, A. L. and A. U. Santos-Paulino (2009). Trading Inequality? Comparing the Two Globalization Waves in Latin America. mimeo. Davis, University of California, Davis. Austin, G. (2005). Labour, Land and Capital in Ghana: From Slavery to Free Labour in Asante, 1807-1956. Rochester, NY, University of Rochester Press. Austin, G. (2008). "Resources, Techniques and Strategies South of the Sahara: Revising the Factor Endowments Perspective on African Economic Development, 1500-2000." Economic History Review 61(3): 587-624. Austin, G. (2008). "The "Reversal of fortune" thesis and the compression of history: perspectives from African and comparative economic history." Journal of International Development 20(8): 996-1027. Balla, E. and N. D. Johnson (2009). "Fiscal Crisis and Institutional Change in the Ottoman Empire and France." Journal of Economic History 69(3): 809-845. Banerjee, A. and L. Iyer (2005). "History, Institutions and Economic Performance: The Legacy of Colonial Land Tenure Systems in India." American Economic Review 95(4): 1190-1213. Bates, R., A. Greif, M. Levi, J-L. Rosenthal, B. Weingast. (1998). Analytic Narratives. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 13 Bértola, L., C. Castelnovo, J. Rodríguez and H. Willebald (2008). Income distribution in the Latin American Southern Cone during the first globalization boom, ca: 1870-1920. Working Papers in Economic History, WP 08-05. Madrid, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. Bogart, D. and L. Chaudhary (2010). Private to Public Ownership: A Historical Perspective from Indian Railways. Working paper. Bolt, J. and D. Bezemer (2009). "Understanding Long-Run African Growth: Colonial Institutions or Colonial Education?" The Journal of Development Studies 45(1): 24-54. Booth, A. E. (2007). Colonial Legacies. Economic and Social Development in East and Southeast Asia. Honolulu, University of Hawai´i Press. Boshoff, W. H. and J. Fourie (2010). "The significance of the Cape trade route to economic activity in the Cape Colony: a medium-term business cycle analysis." European Review of Economic History Forthcoming. Brandt, L. and T. G. Rawski, Eds. (2008). China's Great Economic Transformation , Cambridge University Press Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Broadberry, S. and B. Gupta (2006). "The early modern great divergence: wages, prices and economic development in Europe and Asia, 1500-1800." Economic History Review LIX(1): 2-31. Buelens, F. and S. Marysse (2009). "Returns on investments during the colonial era: the case of the Belgian Congo." Economic History Review 62(S1): 135-166. Bulmer-Thomas, V., J. H. Coatsworth, R. Cortés Condes Eds. (2006). The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America. Cambridge Cambridge University Press. Burgess, R. and D. Donaldson (2010). Can Openness Mitigate the Effects of Weather Fluctuations? Evidence from India’s Famine Era. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings. Chaudhary, L. (2009). "Determinants of Primary Schooling in British India." Journal of Economic History 69(1): 269-302. Chaudhary, L. (2010). "Taxation and Educational Development: Evidence from British India." Explorations in Economic History forthcoming. Clark, G. (2008). "In defense of the Malthusian interpretation of history." European Review of Economic History 12(2): 175-199. 14 Clark, G. and N. Cummins (2009). "Urbanization, Mortality, and Fertility in Malthusian England." American Economic Review 99(2): 242-247. Coatsworth, J. H. (2008). "Inequality, Institutions and Economic Growth in Latin America." Journal of Latin American Studies 40(3): 545-569. Coşgel, M. M. (2004). "Ottoman Tax Registers (Tahrir Defterleri)." Historical Methods 37(2): 87-100. Coşgel, M. M. (2007 ). "Agricultural Productivity in the Early Ottoman Empire." Research in Economic History 24: 161-187. Coşgel, M. M., T. Miceli and R. Ahmed (2009). "Law, State Power, and Taxation in Islamic History." Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 71(3): 704-717. Coşgel, M. M., T. J. Miceli and J. Rubin (2009). Guns and Books: Legitimacy, Revolt and Technological Change in the Ottoman Empire. Working papers: 2009-12. Connecticut, University of Connecticut, Department of Economics. Coşgel, M. M. and T. J. Miceli. (2005). "Risk, Transaction Costs, and Tax Assignment: Government Finance in the Ottoman Empire." Journal of Economic History 65(3): 80682. Dell, M. (2010). "The Persistent Effects of Peru's Mining Mita." Econometrica forthcoming. Diamond, J. (1997). Guns, Germs and Steel: the Fate of Human Societies. New York, Norton. Diamond, J. and J. Robinson (2010). Natural Experiments of History. Cambrige, MA, Harvard University Press. Dobado, R. and H. Garcia (2009). Neither so low nor so short! Wages and Heights in Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries Colonial Latin America. Working paper presented at the workshop "A Comparative Approach to Inequality and Development: Latin America and Europe". Madrid, Universidad Carlos III. Donaldson, D. (2008). Railroads of the Raj: Estimating the Impact of Transportation Infrastructure. Working paper. Edwards, S. (2009). Latin America's Decline: A Long Historical View. NBER Working Paper No. 15171. Elliot, J. H. (2006). Empires of the Atlantic World. Britain adn Spain in America 14921830. New Haven, Yale University Press. 15 Elvin, M. (1973). The Patterns of the Chinese Past. Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press. Fafchamps, M. and A. Moradi (2009). Referral and Job Performance: Evidence from the Ghana Colonial Army. CEPR Discussion Papers 7408, C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers. Fedderke, J. W. and S. Schirmer (2006). "The R&D performance of the South African manufacturing sector, 1970-1993." Economic Change and Restructuring 39(2): 125-151. Fenske, J. (2010). Does land abundance explain African institutions? New Haven, Yale University. Fourie, J. and D. von Fintel (2010). "The dynamics of inequality in a newly settled, preIndustrial society: Evidence from Cape Colony tax records." Cliometrica 4(3). Frankema, E. H. P. (2009). Has Latin America Always Been Unequal? A comparative study of asset and income inequality in the long twentieth century. Leiden, Boston, Brill. Green, E. (2009). "A lasting story: Conservation and Agricultural Extension Services in Colonial Malawi." Journal of African History 50(2). Hejeebu, S. (2005). "Contract Enforcement in the English East India Company." Journal of Economic History 65(2): 1-27. Hoffman, P. and P. Fishback (2009). "Editor's Notes." The Journal of Economic History 69(1): 303-311. Hopkins, A. G. (1973). An economic history of West Africa. London, Longman. Hopkins, A. G. (2009). "The New Economic History of Africa." The Journal of African History 50(2): 155-177 Huillery, E. (2009). "History Matters: The Long-Term Impact of Colonial Public Investments in French West Africa." American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1(2): 176-215. Irigoin, M. A. and R. Grafe (2008). "Bargaining for Absolutism: A Spanish Path to Nation-State and Empire Building." Hispanic American Historical Review 88(2): 173209. İyigün, M. (2008). "Luther and Suleyman." Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(4): 1465-1494. Jha, S. (2008). Trade, institutions and religious tolerance: evidence from India. Research Paper No. 2004. Cambridge, MA, Stanford GSB. 16 Kranton, R. and A. Swamy (2008). "Contracts, Hold-Up, and Exports: Textiles and Opium in Colonial India." American Economic Review 98(3): 967-989. Kumar, D., Ed. (1983). The Cambridge Economic History of India Vol. 2 c.1757- c.1970. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Kuran, T. (2004). "Why the Middle East is Economically Underdeveloped: Historical Mechanisms of Institutional Stagnation." Journal of Economic Perspectives 18(3): 71-90. La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes and A. Shleifer (2008). "The Economic Consequences of Legal Origins." Journal of Economic Literature 46: 285-332. Landes, D. S. (1998). The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor New York, W.W. Norton & Company. Lin, J. Y. (1995). "The Needham Puzzle: why the industrial revolution did not originate in China." Economic Development and Cultural Change 43(2): 269-292. Ma, D. (2008). "Economic Growth in the Lower Yangzi Region of China in 1911-1937: A Quantitative and Historical Analysis." Journal of Economic History 68(2): 355-392. Marichal, C. (2007). Bankruptcy of Empire. Mexican Silver and the Wars between Spain, Britain and France, 1760-1810. Cambridge MA, Cambridge University Press. Mariotti, M. (2009). Labor Markets During Apartheid in South Africa. Working Papers in Economics and Econometrics. Canberra, Australian National University. Milanovic, B., P. H. Lindert and J. Williamson (2008). Measuring Ancient Inequality. NBER Working Paper No. 13550. Mitchener, K. J. and S. Yan (2010). Globalization, Trade & Wages: What Does History Tell us about China? NBER Working Paper 15679 Cambridge, MA, National Bureau of Economic Research. Moradi, A. (2009). "Towards an Objective Account of Nutrition and Health in Colonial Kenya: A Study of Stature in African Army Recruits and Civilians, 1880-1980." The Journal of Economic History 69(3): 719-754. North, D. C., W. Summerhill and B.R. Weingast (2000). Order, Disorder and Economic Change: Latin America versus North America. Governing for Prosperity. B. Bueno de Mesquita and H. L. Root. New Haven, Yale University Press. Nunn, N. (2008). "The Long Term Effects of Africa's Slave Trades." Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(1): 139-176. Nunn, N. (2009). Christians in Colonial Africa. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University. 17 Nunn, N. (2009). "The Importance of History for Economic Development." Annual Review of Economics 1(1): 65-92. Nunn, N. (2010). Shackled to the Past: The Causes and Consequences of Africa's Slave Trade. Natural Experiments of History. J. Diamond and J. Robinson. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press: 142-184. Nunn, N. and D. Puga (2009). Ruggedness: The Blessing of Bad Geography in Africa. NBER Working Papers 14918. Cambridge, MA, National Bureau of Economic Research. Nunn, N. and L. Wantchekon (2009). The Slave Trade and the Origins of Mistrust in Africa. NBER Working Papers 14783. Cambridge, MA, National Bureau of Economic Research. Özmucur, S. and Ş. Pamuk (2002). "Real Wages and Standards of Living in the Ottoman Empire, 1489-1914." Journal of Economic History 62(2): 293-321. Pamuk, Ş. (2000). A Monetary History of the Ottoman Empire. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Parthasarathi, P. (1998). "Rethinking wages and competitiveness in the eighteenth century: Britain and south India." Past and Present 158(1): 79-109. Pomeranz, K. (2000). The Great divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy. Princeton, Princeton University Press. Prados de la Escosura, L. (2005). Growth, Inequality and Poverty in Latin America: Historical Evidence, Controlled Conjectures. Working Papers in Economic History, WP 05-41. Madrid, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. Prebish, R. (1962). El Desarrollo Económico de América Latina y Algunos de Sus Principales Problemas, in: , . Boletín Económico América Latina. Santiago de Chile, CEPAL-UNCLA. Roy, T. (2000). The Economic History of India 1847-1947. Delhi, Oxford University Press. Roy, T. (2002). "Economic history and modern India: redefining the link." Journal of Economic History 16(3): 109-130. Roy, T. (2004). "Flourishing branches, wilting core: research in modern Indian economic history." Australian Economic History Review 44(3): 221-240. Roy, T. (2010). "Economic Conditions in Early Modern Bengal: A contribution to the Divergence Debate." Journal of Economic History forthcoming. 18 Rubin, J. (2010). "Bills of Exchange, Interest Bans, and Impersonal Exchange in Islam and Christianity." Explorations in Economic History forthcoming. Shiue, C. H. (2002). "Transport Costs and the Geography of Arbitrage in Eighteenth Century China." American Economic Review 92(5): 1406-1419. Shiue, C. H. and W. Keller (2007). "Markets in China and Europe on the Eve of the Industrial Revolution." American Economic Review 97(4): 1189-1216. Sokoloff, K. L. and S. L. Engerman (2000). "History Lessons." Journal of Economic Perspectives 14(3): 217-232. Sokoloff, K. L. and S. L. Engerman (2000). "History Lessons: Institutions, Factor Endowments, and Paths of Development in the New World." Journal of Economic Perspectives 14(3): 217-232. Stegl, M. and J. Baten (2009). "Tall and Shrinking Muslims, Short and Growing Europeans: The Long-Run Welfare Development of the Middle East, 1850-1980." Explorations in Economic History 46(1): 132-148. Studer, R. (2008). "India and the Great Divergence: Assessing the Efficiency of Grain Markets in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century India." Journal of Economic History 68(2): 393-437. Taylor, A. M. (2006). Foreign Capital Flows. The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America: The Long Twentieth Century. V. Bulmer-Thomas, J. H. Coatsworth and R. Cortés Conde. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. II. Williamson, J., G. (1998). Real Wages and Relative Factor Prices in the Third World 1820-1940: Latin America Discussion Paper Number 1853, Harvard Institute of Economic Research Williamson, J. G. (2009). History Without Evidence: Latin American Inequality Since 1491. NBER Working Paper Series Yan, S. (2008). Real Wages and Skill Premia in China, 1858 to 1936. Department of Economics. California, UCLA. Zelin, M. (2005). The Merchants of Zigong, Industrial Entrepreneurship in Early Modern China. New York, NY, Columbia University Press. 19