Translation from Spanish to English

advertisement

Traductorado Público, Literario y

Científico-Técnico de Inglés

Translation from Spanish

to English

Profesor:

Douglas Andrew Town

Douglas Andrew Town

Translation from Spanish to English

1

Translation from Spanish to English

FOR MARISA

2

Translation from Spanish to English

Table of Contents

Preface

Part One: From Words to Text

1. Vocabulary in context

1.1

Las trufas - Isabel Allende

1.2

Vestir una sombra - Julio Cortázar

1.3

Emma Zunz – Jose Luis Borges

1.4

Estación de la mano- Julio Cortázar

Translation commentary on Estación de la mano

2. Translating different meanings of “se”

2.1

La Regenta - Leopoldo Alas, ‘Clarín’,

2.2

Corazón tan blanco - Javier Marías

3. Tense, aspect and mood

3.1

Corazón tan blanco - Javier Marías

Translation commentary on Corazón tan blanco

3.2

Continuidad de los parques - Julio Cortázar

Literary commentary on Continuidad de los parques

4. Explaining cultural items

4.1

Two extracts from John Hooper’s The New Spaniards

A Cult of Excess

The Taming of ‘The Bulls’

4.2

Caballos en el Corazón - Alberto Catena

4.3

El Oro Verde Conquista al Mundo - Fidel Euterpe

4.4

El sistema español de mediación y arbitraje – Unión Europea

5. Clarifying the syntax

5.1

Rewriting expository prose in clear Spanish

El debate sobre la reforma del Estado

5.2

Reducing “noise” in translation

Doce lecciones sobre Europa – Pascal Fontaine

5.3

Rewriting narrative prose in English

6. Information flow within the paragraph

6.1

Los Músicos del Plata

6.2

English for Technical Writing - Ruth Munilla

6.3

Ingredients of a successful paragraph

6.4

Detailed argumentative paragraphs - Melissa Hilton

6.5

The 5-paragraph essay

6.6

Recognising Language Functions

7. Parallel Strucure and Contrast

7.1

Las matanzas de indígenas – Daniel Feierstein

7.2

Libro de Guisados (1529)

3

Translation from Spanish to English

7.3

7.4

Emprendedores innovadores - Alejandro Gómez

Asados y Parrillas – Alberto Vázquez Prego

8. Concreteness vs. Abstraction

8.1

Doce lecciones sobre Europa – Pascal Fontaine

8.2

Evolution of family textile consumption

9. Paragraph Division

9.1

Caballos en el Corazón - Alberto Catena

9.2

Original or translated? Two texts about the Oedipus complex

9.3

Discourse Features of Written Mexican Spanish –

María Rosario Montaño-Harmon

10. Reader centred prose

10.1 Reader centred vs. Writer centred prose

10.2 Restructuring and expanding the writer centred

text to make it reader centred

11.Pragmatic functions

11.1 LKM website - Commissives

11.2 LKM website - Reducing pragmatic “noise” in a badly written text

11.3 LKM website - Matching discourse and pragmatic functions

11.4 Té literario - Juan Ramón Ribeyro

Politeness and modal verbs

12. Skopos

11.1

11.2

11.3

11.4

11.5

11.6

11.7

Córdoba

Hotel y Complejo Paihuen

Peter Pan – El Loco

Integrated Natural Resource Management

A Brief History of George Smiley – John Le Carré

Las Trufas - Isabel Allende

Fiebre Negra - Miguel Rosenzvit

Part Two. Annotated Passages for Translation

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Sobre la Ciudad

El Agro en la Argentina

Arte Español para el Exterior

Variación y Cambio en el Español

Las obras de Infraestructura

La Unión Permite Exportar

Entelman Peacemeakers

Part Three: Process and procedures

1.

2.

A Brief Summary of the Translation Process

More about Translation Procedures

4

Translation from Spanish to English

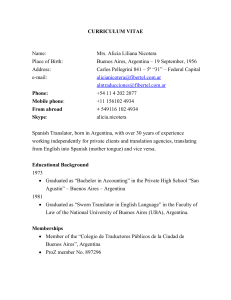

Preface

Argentinean translators have a long tradition of translating out of their native language

and demand for their services is growing steadily in all areas. Nevertheless, most training

programmes in Argentina still concentrate almost exclusively on legal, technical and

scientific translation. In contrast, other subject areas are dealt with less intensively and, on

the whole, there is little consensus about what to teach or how to teach it. This problem is

not exclusive to Argentina and has to do with differences in the subject matter and

professional status of different translation areas. Most specialised texts, such as contracts,

medical records and computer manuals, have clearly defined topics, purposes and readers

and so allow for systematic comparisons of layout, phraseology and terminology in the

source and target languages. Moreover, in areas such as law, medicine and technology,

where mistakes and ambiguities can lead to financial loss, injury or even death, courses are

expected to meet certain legal or professional standards.

In other areas of translation, however, a contrastive approach is more problematic.

Imagine that we wish to compare travel guides in Spanish and English. Now, the content

and style of a travel guide depends partly on its objectives – e.g. to provide information

about local landmarks and culture, to promote goods and services, to entertain the reader –

and partly on the age and socio-economic status of the target audience and the idiosyncrasies

of the author and/or publisher. But even if we collect a veritable corpus of guide books in

each language and classify them along these lines, it may still be difficult to match specific

texts about (say) Buenos Aires or Madrid with “equivalent” texts about London, New York

or Sydney. Despite the global tourist industry, each city is unique and, in any case, different

cultures inevitably make different assumptions about what is important, interesting, trendy

or sophisticated. Consequently, few translation schools are prepared to invest in research

into this or other areas of “general” translation, especially as there is no legal or professional

requirement to do so. Even so, this does not rule out a more systematic way of approaching

non-specialized translation than the trial and error method commonly used at present.

This book offers practice at undergraduate level in literary, general and semi-specialized

translation from Spanish into English. It is aimed at Spanish speakers with a good level of

English as a second language (Cambridge Advanced Certificate or higher) and is systematic

in that it integrates translation practice with translation and textual analysis, including

analysis of texts originally written in English. The tasks in Part One become increasingly

more complex as the focus shifts to larger units of language. The annotated passages for

translation in Part Two are similarly graded. In addition, I have included a number of

articles on Contrastive Rhetoric, extended paragraph writing and Technical Writing as well

as extended translation commentaries on various texts. The articles are intended to draw

attention to the rhetorical conventions of each language that work at the paragraph level and

beyond, while at least two of the commentaries focus mainly on problems at the sentence

level. There is also a literary analysis in Spanish on Julio Cortázar’s short story Continuidad

de los Parques.

Douglas Town

Buenos Aires, 2009

5

Translation from Spanish to English

Part One: From Words to Text

6

Translation from Spanish to English

1. Vocabulary in context

Task 1.1: Chose the most appropriate translation for the words and expressions

underlined. Give reasons for your choices.

Las trufas

Napoleón las comía antes de (1) enfrentarse con Josefina en las batallas (2) amorosas del

(3) dormitorio imperial, en las cuales, (4) no está de más decirlo, siempre (5) salía

derrotado... Los científicos — ¿cómo se les ocurren estos experimentos, digo yo?— han

descubierto que el olor del hongo activa una glándula en (6) el cerdo que produce las

mismas feromonas presentes en los seres humanos cuando son (7) golpeados por el amor.

Es un (8) olorcillo a (9) sudor con ajo que (10) recuerda el (11) metro de Nueva York.

Hace algunos años invité a cenar, (12 ) con intención de seducirlo, claro está, a un (13 )

escurridizo galán, cuya fama de buen cocinero (14) me obligaba a esmerarme con el menú.

Decidí que (15 ) una omelette de trufas (16) salpicada con una ( 17) nubecilla de caviar

rojo al servirla (el gris estaba lejos de mis posibilidades), constituía una (18) invitación

erótica obvia, (19 ) algo así como regalarle rosas rojas y el Kama Sutra. Busqué las trufas

(20 ) por cielo y tierra y cuando finalmente (21 ) di con ellas, mi modesto (22) presupuesto

(23) de inmigrante en tierra ajena (24 ) no alcanzó para comprarlas. El dependiente de la

tienda de delicatessen, un italiano (25) tan inmigrante como yo, me aconsejó (26 )

olvidarme de ellas.

From: Isabel Allende Afrodita (1997)

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

a.

b.

c.

d.

confronting

clashing with

facing

meeting

a.

b.

c.

d.

affectionate

amorous

cute

loving

a.

b.

c.

d.

alcove

bedchamber

bedroom

dormitory

a. it is no exaggeration to sa

b. it is worth pointing out

c. needless to say

a. came out beaten

b. wound up defeated

c. was despondent

6.

7.

8.

9.

a.

b.

c.

d.

the pig

pigs

pork

swine

a.

b.

c.

d.

infatuated

lovesick

pining

smitten by love.

a.

b.

c.

d.

odor

reek

smell

tang

a.

b.

c.

d.

garlicky perspiration

sweat and garlic

garlic with sweat

sweaty, garlic-tinged

7

Translation from Spanish to English

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

a.

b.

c.

d.

recalls

is redolent of

remembers

reminds

a.

b.

c.

d.

metro

subway

tube

underground

18.

19.

20.

a.

b.

c.

d.

in an attempt to

with intent to

with intentions of

with the aim of

21.

a.

b.

c.

d.

an evasive beau

a shifty pretender

a slippery suitor

a wild heartthrob

22.

a. forced me to outdo myself

b. made me do my best

c. obliged me go to a lot of trouble

a. a truffle omelet

b. an omelet with truffle

c. an omelet with truffles

a.

b.

c.

d.

peppered with

showered with

splashed with

sprinkled with

a. a dusting of red caviar

b. a cloud of red caviar

c. a red caviar garnish

23.

24.

25.

26.

a.

b.

c.

d.

call

invitation

overture

summons

a.

b.

c.

d.

like

similar to

something akin to

something like

a.

b.

c.

d.

far and wide

high and low

in every nook and cranny

up and down

a.

b.

c.

d.

come up with some

located some

met them

stumbled across them

a.

b.

c.

d.

budget

finances

funds

salary

a.

b.

c.

d.

in a land not my own

on alien territory

in foreign parts

on a foreign shore

a. could not manage to

b. failed to

c. would not stretch far enough to

a. as much an immigrant as I

b. an immigrant like me

c. who has migrated like me

a. to forget the truffles

b. to forget them

c. to forget about them

8

Translation from Spanish to English

Task 1.2: Chose the most appropriate translation for the words and expressions

underlined. Give reasons for your choices.

Vestir una sombra

Julio Cortázar

Lo más difícil es (1) cercarla, (2) conocer su límite allí donde (3) se enlaza con la penumbra

(4) al borde de sí misma. Escogerla entre tantas otras, apartarla de la luz que toda sombra

respira sigilosa, peligrosamente.

Empezar entonces a vestirla (5) como distraído, sin moverse demasiado, sin asustarla o

disolverla: operación inicial donde (6) la nada (7) se agazapa en cada (8) gesto. La (9) ropa

interior, el transparente (10) corpiño, las (11) medias que dibujan un ascenso sedoso hacia

los muslos. Todo lo consentirá en su momentánea ignorancia, como si todavía creyera estar

jugando con otra sombra, pero bruscamente se inquietará cuando la falda (12) ciña su

cintura y sienta los dedos que abotonan la blusa entre los (13) senos, (14) rozando la (15)

garganta que (16) se alza hasta perderse en un oscuro (17) surtidor. (18) Rechazará el (19)

gesto de coronarla con la peluca de (20) flotante pelo rubio (¡ese halo tembloroso rodeando

un rostro inexistente!) y (21) habrá que (22) apresurarse a dibujar la boca con (23) la brasa

del cigarrillo, (24) deslizar sortijas y pulseras para darle esas manos con que resistirá

inciertamente mientras los labios (25) apenas nacidos murmuran el (26) plañido inmemorial

de quien (27) despierta al mundo. (28) Faltarán los ojos, que han de (29) brotar de las

lágrimas, la sombra por sí misma completándose para mejor (30) luchar, para (31) negarse.

Inútilmente conmovedora cuando el mismo impulso que la vistió, la misma sed de verla (32)

asomar perfecta del confuso espacio, la envuelva en su (33) juncal de caricias, comience a

desnudarla, a descubrir, por primera vez su forma que vanamente busca (34) cobijarse tras

manos y súplicas, cediendo lentamente a la caída entre un (35) brillar de anillos que rasgan

en el aire sus luciérnagas (36) húmedas.

1.

2.

3.

4.

a.

b.

c.

d.

enclose

encircle

fence

surround

a.

b.

c.

d.

fix

identify

know

meet

a.

b.

c.

d.

connects with

fades into

joins

links up with

a.

b.

c.

d.

along its edge

along its border

on its own border

on the edge of itself

5.

6.

7.

8.

a.

b.

c.

d.

absentmindedly

carelessly

casually

distractedly

a.

b.

c.

d.

nonexistence

nothing

nothingness

the void

a.

b.

c.

d.

cowers

crouches

squats

lies

a.

b.

c.

d.

gesture

gesticulation

motion

move

9

Translation from Spanish to English

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

a.

b.

c.

d.

inner garments

lingerie

under clothes

underwear

a.

b.

c.

d.

bodice

bra

brassiere

corset

a.

b.

c.

d.

leggings

pantyhose

socks

stockings

a.

b.

c.

d.

is tight around

clings to

encircles

girds

a.

b.

c.

d.

bosom

breasts

bust

chest

a.

b.

c.

d.

brushing

grazing

rubbing against

touching upon

a.

b.

c.

d.

gorge

gullet

neck

throat

a.

b.

c.

d.

goes up

mounts

rises

soars

a.

b.

c.

d.

flowing water

fountain

jet

pump

a.

b.

c.

d.

decline

reject

repel

turn down

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

a.

b.

c.

d.

gesture

gesticulation

motion

move

a.

b.

c.

d.

floating

flowing

long

streaming

a.

b.

c.

d.

it behooves you

it is necessary to

you have to

you must

a.

b.

c.

d.

hasten

hurry

rush

work quickly

a.

b.

c.

d.

cigarette embers,

cigarette ash

cinders

fag ends

a.

b.

c.

d.

glide

run

slide

slip on

a.

b.

c.

d.

infant

neonatal

newborn

newly formed

a.

b.

c.

d.

crying

howls

lament

weeping

a.

b.

c.

d.

is aroused by

awakens to

wakes up to

wises up to

a.

b.

c.

d.

it will need

will be needed

will be missing

will be necessary

10

Translation from Spanish to English

29.

30.

31.

32.

a.

b.

c.

d.

be made from

flow from

spring up from

well up in

a.

b.

c.

d.

battle

fight

resist

struggle

a.

b.

c.

d.

cancel itself out

deny itself

negate itself

repudiate itself

a.

b.

c.

d.

appear

born

lean out

take shape

33.

34.

35.

36.

a.

b.

c.

d.

reed bed

rush patch

thicket

undergrowth

a.

b.

c.

d.

conceal

protect

take shelter

take cover

a.

b.

c.

d.

flash

glare

glimmer

glint

a.

b.

c.

d.

damp

glittering

glistening

moist

11

Translation from Spanish to English

Task 1.3: Chose the most appropriate translation for the words and expressions

underlined. Give reasons for your choices.

Emma Zunz

El catorce de enero de 1922, Emma Zunz, (1) al volver de la (2) fábrica de tejidos Tarbuch

y Loewenthal, (3) halló (4) en el fondo del zaguán una carta, (5) fechada en el Brasil, por

la que aupo1 que su padre había muerto. La (6) engañaron, a primera vista, el sello y el

sobre; luego, (7) la inquietó la letra (8) desconocida. Nueve o diez líneas (9) borroneadas

querían (10) colmar la hoja; Emma leyó que el señor Maier había (11) ingerido por error una

fuerte dosis de veronal y había fallecido el tres del corriente en el hospital de Bagé.z Un

(12) compañero de pensión de su padre firmaba la (13) noticia, un tal Fein o Fain, de Río

Grande, que (14) no podía saber que se dirigía a la hija del muerto.

Emma (15) dejó caer el papel. Su primera impresión fue de (16) malestar en el vientre y

en las rodillas; luego de ciega culpa, de irrealidad, de frío, de temor; luego, quiso ya estar

en el día siguiente. Acto continuo comprendió que (17) esa voluntad era inútil porque la

muerte de su padre era lo único que había sucedido en el mundo, y seguiría sucediendo sin

fin. Recogió el papel y se fue a su cuarto. Furtivamente lo (18) guardó en un cajón, como si

de algún modo ya conociera los (19) hechos ulteriores. Ya había empezado a (20)

vislumbrarlos, tal vez; ya era (21) la que sería.

En la creciente oscuridad, Emma (22) lloró hasta el fin de aquel día el suicidio de

Manuel Maier, que en los (23) antiguos días felices fue Emanuel Zunz. Recordó veraneos

en una chacra, cerca de Gualeguay,* recordó (trató de recordar) a su madre, recordó la

casita de Lanús6 que les (24) remataron, recordó los amarillos losanges de una Ventana,

recordó el (25) auto de prisión, el (26) oprobio, recordó los (27) anónimos con el (28)

suelto sobre «el desfalco del cajero»,…

José Luis Borges Emma Zunz

1.

2.

3.

4.

a.

b.

c.

d.

on returning home

on getting home

when she returned home

when she was coming

a.

b.

c.

d.

cloth factory

clothes factory

fabric mill

textile mill

a.

b.

c.

d.

came across

discovered

encountered

found

a.

b.

c.

d.

along the hallway

at the back of the hall

at the rear of the entrance hall

in the entrance

5.

6.

7.

8.

a.

b.

c.

d.

dated

posted

postmarked

stamped

a.

b.

c.

d.

cheated

deceived

deluded

misled

a.

b.

c.

d.

disturbed her

made her restless

made her anxious

made her uneasy

a.

b.

c.

d.

mysterious

strange

unfamiliar

unknown

12

Translation from Spanish to English

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

a.

b.

c.

d.

grubby

illegible

scrawled

scribbled

a.

b.

c.

d.

complete

cram

fill up

fulfill

a.

b.

c.

d.

accidentally swallowed

erroneously consumed

mistakenly

taken by mistake

a.

b.

c.

d.

accommodation

boarding house friend

fellow pensioner

roommate

a.

b.

c.

d.

letter

news

notification

piece of news

a.

b.

c.

d.

may not have known

cannot have known

had no way of knowing

was unable to know

a.

b.

c.

d.

dropped the sheet of paper

dropped the piece of paper

let go of the letter

let the paper fall

a.

b.

c.

d.

a sick feeling in her bowels

a weak feeling in her stomach

discomfort in her abdomen

unease in her belly

a.

b.

c.

d.

the will was useless

that wish was futile

her willingness was useless

her wistfulness was pointless

a.

b.

c.

d.

hid

guarded

kept

put away

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

a.

b.

c.

d.

hidden events

later deeds

subsequent facts

ulterior actions

a.

b.

c.

d.

discern

glimpse

make out

suspect

a.

b.

c.

d.

the one

the person

the woman

who

a.

b.

c.

d.

cried

mourned

sobbed

wept

a.

b.

c.

d.

happy old days

old happy days

good old days

bygone days

a.

b.

c.

d.

had been auctioned for them

had been auctioned off

had been publicly auctioned

had been put up for auction

a.

b.

c.

d.

the committal for trial

the court sentence

the prison van

the warrant for arrest

a.

b.

c.

d.

the disgrace

the dishonor

the ignominy

the opprobrium

a.

b.

c.

d.

anonymous authors

poison pen letters

ransom notes

unsigned articles

a.

b.

c.

d.

loose change

short item

newspaper’s account

release

13

Translation from Spanish to English

Task 1.4: Below is an extract from Julio Cortázar’s (1967) short story ‘Estación de la

mano’ – a tale of the unexpected that achieves its effect by combining the ordinary with the

literary and ‘scientific’. First, underline the literary and ‘scientific’ elements in the ST. Then

decide which of the idiomatic translations in the TT are also ‘explicitations’. Finally, read

the notes beneath the text.

‘Estación de la mano’

‘The Time of the Hand’

Le puse nombres: me gustaba llamarla Dg,

porque era un nombre que sólo se dejaba

pensar. Incité su probable vanidad olvidando

anillos y brazaletes sobre las repisas, espiando

su actitud con secreta constancia. Alguna vez

creí que se adornaría con las joyas, pero ella

las estudiaba dando vueltas en torno y sin

tocarlas, a semejanza de una araña

desconfiada; y aunque un día llegó a ponerse

un anillo de amatista fue sólo por un instante,

y lo abandonó como si le quemara. Me

apresuré entonces a esconder las joyas en su

ausencia y desde entonces me pareció que

estaba más contenta.

I invented names for It: the one I liked best

was Dg, because this was a name one could

only think, but not say.1 I tried to arouse its

suspected 2 vanity by leaving rings and

bracelets lying around on the shelves, while in

secret I observed its reaction constantly.3 On

one occasion I thought It was about to put on 4

the jewels, but It turned out to be merely

examining them, circling round and round

without touching them, just like a wary

spider.5 Once It did actually venture to put on

an amethyst ring, though only for an instant,

discarding it immediately as if it were red hot.

6

After that, I quickly hid the jewels while It

was away, and from then on I had the

impression that It was much happier.

Así declinaron las estaciones, unas esbeltas y

otras con semanas teñidas de luces violetas,

sin que sus llamadas premiosas llegaran hasta

nuestro ámbito. Todas las tardes volvía la

mano, mojada con frecuencia por las lluvias

otoñales, y la veía tenderse de espaldas sobre

la alfombra, secarse prolijamente un dedo con

otro, a veces con menudos saltos de cosa

satisfecha. En los atardeceres de frío su

sombra se teñía de violeta. Yo encendía

entonces un brasero a mis pies y ella se

acurrucaba y apenas bullía, salvo para recibir,

displicente, un álbum con grabados o un ovillo

de lana que le gustaba anudar y retorcer. Era

incapaz, lo advertí pronto, de estarse largo rato

quieta. Un día encontró una artesa con arcilla y

se precipitó sobre ella; horas y horas modeló la

arcilla mientras yo, de espaldas, fingía no

preocuparme por su tarea. Naturalmente,

modeló una mano. La dejé secar y la puse

sobre el escritorio para probarle que su obra

me agradaba. Era un error: a Dg terminó por

molestarle la contemplación de ese

autorretrato rígido y algo convulso. Cuando lo

escondí, fingió por pudor no haberlo

advertido.

Thus 7 the seasons came and went, some

gracefully, others with flickering weeks, 8

without disturbing our cosy routine. Every

afternoon the hand would arrive, often wet

with the autumn rain, and I would see her 9

lying on her back on the carpet, meticulously

drying one finger with another, and giving

little shivers of apparent contentment.10 On

cold evenings her shadow would take on a

violet hue. Then I would light a brazier 11 at

my feet and she would cuddle up to it, only

stirring half heartedly 12 to accept an album of

pictures to leaf through, or a ball of wool

which she enjoyed twisting and tangling. She

was, as I soon learned, incapable of staying

still for long. One day she came across a

trough full of clay which she fell upon avidly;

for hours and hours she went on moulding the

clay while I, with my back to her, pretended

not to notice what she was doing.13 Not

unexpectedly, she had sculpted 14 a hand. I let

it dry and placed it on my desk to show that I

liked it. This turned out to be a mistake:

looking at 15 her rigid and somewhat distorted

self-portrait soon came to irritate her. When I

hid the object, 16 she tactfully pretended not to

have noticed.

14

Translation from Spanish to English

Mi interés se tornó bien pronto analítico.

Cansado de maravillarme, quise saber,

invariable y funesto fin de toda aventura.

Surgían las preguntas acerca de mi huésped:

¿Vegetaba, sentía, comprendía, amaba? Tendí

lazos, apronté experimentos. Había advertido

que la mano, aunque capaz de leer, jamás

escribía. Una tarde abrí la ventana y puse

sobre la mesa un lapicero, cuartillas en blanco

y cuando entró Dg me marché para no pesar

sobre su timidez. Por el ojo de la cerradura la

vi cumplir sus paseos habituales; luego,

vacilante, fue hasta el escritorio y tomó el

lapicero. Oí el arañar de la pluma, y después

de un tiempo ansioso entré en el estudio. En

diagonal y con letra perfilada, Dg había

escrito: Esta resolución anula todas las

anteriores hasta nueva orden. Jamás pude

lograr que volviese a escribir.

Julio Cortázar, Los relatos: 2, Juegos (Madrid:

Alianza, 1976, pp. 57–8),

Soon my interest in the hand became

analytical. Tired of treating it 17 as an object of

wonder, I now wanted to know, which 18

always spells the inevitable and fateful end to

all adventures. I was plagued by questions

about my strange guest. Did it grow? Could it

feel? Could it understand? Did it love? 19 I set

up tests and devised experiments. I had found

out that the hand could read, and yet never

wrote. One afternoon, I opened the window

and placed a pen and some blank sheets of

paper on the table, and when Dg came in I

withdrew so as not to disturb the timid

creature. Through the keyhole I observed it as

it did its usual rounds of the room; then,

hesitantly, it approached the desk and took up

the pen. I heard the scratching of the nib, and

after an uneasy wait I entered the study.

Diagonally across the page, penned in a neat

hand, it had written: ‘This resolution cancels

all previous ones until further notice.’20 I could

never induce it to write again.

Thinking Spanish Translation Teachers’

Handbook

1 The TT departs from literal translation by expanding the rendering of ‘un nombre que sólo se

dejaba pensar’ by adding ‘but not say’, without which the TT would be incomprehensible. In our

view, the alternatives ‘a name which can only be thought’ or ‘a name which one can only think’

are almost ungrammatical, and are certainly obscure: the point made in the ST (which is the

suitability of an unpronounceable name for an extraordinary creature) has to be made more

explicit in the TT if it is to be grasped.

2 The more literal meaning of ‘probable’ is inappropriate to the context: the point is not that the

creature’s vanity is objectively probable, but that the narrator thinks it might be vain.

3 The more literal ‘with secret constancy/persistence’ has been rejected as translationese. Our

solution involves substantial grammatical transposition: the adjective ‘secreta’ is transposed to

the adverbial complement ‘in secret’ and the noun ‘constancia’ to the adverb ‘constantly’.

4 The more literal rendering ‘adorn itself with’ is rejected as translationese: despite the resulting

translation loss (see, in particular, the connection between ‘se adornaría’ and ‘su probable

vanidad’) the more neutral and colourless ‘put on’ is preferable.

5 The aptness of the simile is not fully appreciated until the subsequent context reveals that Dg

is really a disembodied hand; it is all the more important to ensure that the image of the spiderlike movements is clearly conveyed in the TT.

6 Using the phrase ‘red hot’, besides being idiomatic in context, avoids the need for further

repetition of anaphoric ‘it’; had we not used ‘It’ for denoting Dg, this sentence would have

become both cumbersome and potentially confusing as a result of too many occurrences of ‘it’,

some referring to Dg and some to the amethyst ring.

7 The degree of ‘purple style’ in this sentence justifies the use of the more formal connective

‘thus’, in preference to a more colloquial alternative such as ‘So...’.

15

Translation from Spanish to English

8 The more literally exact ‘tinged/tinted with violet lights’, while retaining the ‘purple’ style of

the ST, is felt to be unidiomatic to the point of translationese. We feel that this phrase contrasts

(note the structure ‘unas …y otras’, and the difference in phrase length introduced by each) with

the previous one to convey the different speeds with which time appears to pass, and we aim to

combine this and the image of light in our solution to retain the literary flavour of the ST

without jeopardizing TL idiomaticity.

9 The shift to anaphoric ‘she’ signals a change in the narrator’s attitude to Dg during this period

of ‘cosy routine’ (see our strategic comments above).

10 In describing the details of Dg’s behaviour literal faithfulness to the ST is far less important

than finding plausible ways of recreating in the TT the appropriate visual images: implicitly, the

creature is described as behaving like a pet, but there is a reminder of its unusual nature in

‘secarse prolijamente un dedo con otro’. We considered a TL collocation like ‘little jumps of

joy’ but ruled this out on the grounds that ‘cosa satisfecha’ maintains the note of weirdness

prevalent in the passage.

11 The reference is to a small charcoal heater of the kind often used in Spanish and Latin

American households. The object itself is culturally alien to the Anglophone reader, and no

serious translation loss would have resulted from describing it simply as ‘a heater’; the cultural

strangeness of ‘a brazier’ injects a slight degree of exoticism into the TT, which helps to

distance the narrative from ordinary experience.

12 The choice of ‘half heartedly’ represents a literally inexact, but idiomatically justified and

contextually apt rendering of ‘displicente’.

13 There is a substantial grammatical transposition in this solution, in order to avoid unidiomatic

nominal constructions in the TT: formulations like ‘pretended not to be preoccupied with its

activity’ would constitute conspicuous translationese.

14 Tense causes a problem of detail in the TT: in the context, ‘sculpted’, ‘was sculpting’ and

‘had sculpted’ are all plausible alternatives. We chose ‘had sculpted’ in order to pick up the

narrative at the point when the sculpture was finished.

15 The grammatical transposition (in particular the avoidance of an abstract nominal

‘contemplation’) necessary for producing an idiomatic rendering further suggests that

‘contemplating’ is too formal and pedantic in the context: we chose to replace it by the more

neutral and colloquial ‘looking at’.

16 Although anaphoric ‘it’ could be used here, the TT becomes clearer and more felicitous

through the insertion of ‘the object’, in particular through the contextually apt collocative echo

of the cliché ‘the offending object’.

17 The shift to anaphoric ‘it’ signals yet another change in the narrator’s attitude to Dg: this time

to treating it as an object of scientific curiosity (see strategic comments).

18 With the aid of punctuation the TT can be correctly construed as meaning that the quest for

analytical knowledge invariably puts an end to the romance of adventure. This construal is not

immediately obvious in the ST, which, if the function of the comma after ‘saber’ is ignored, can

be easily misconstrued by interpreting ‘invariable y funesto fin de toda aventura’ as the

grammatical object of ‘saber’.

19 The variation between ‘did it’ and ‘could it’ is justified purely by reasons of collocational

felicity in English.

20 Communicative translation is appropriate here: the written message must read like a plausible

official memo in English, hence the use of bureaucratic jargon in our TT.

Thinking Spanish Translation Teachers’ Handbook

16

Translation from Spanish to English

2. Translating different meanings of “se”

1 [seguido de otro pronombre: sustituyendo a le]: ya se lo he dicho (a él) -- I’ve already

told him; (a ella) I’ve already told her; (a usted, ustedes) I’ve already told you; (a ellos) I’ve

already told them;

el vestido tenía cuello pero se lo quité -- the dress had a collar but I took it off

2 (en verbos pronominales): se queja de todo -- « él/ella » he/she complains about

everything; -- « usted » you complain about everything;

¿no se arrepienten? -- « ellos/ellas » aren’t they sorry?; -- « ustedes » aren’t you sorry?;

el barco se hundió -- the ship sank;

se cortó (refl) -- he cut himself; se cortó el dedo (refl) -- he cut his finger;

(por accidente, sin intención) se me cayó - - I dropped it, it slipped out of may hand; se me

rompió – I broke it, it broke

se hizo un vestido (refl) -- she made herself a dress;

se hizo un vestido (caus) -- she had a dress made;

no se hablan (recípr) -- they’re not on speaking terms, they’re not speaking to each other;

se lo comió todo (enf) -- he ate it all, he ate the whole thing

3 a (voz pasiva):

se oyeron unos gritos -- there were shouts;

se estudiarán sus propuestas -- your proposals will be studied;

se publicó el año pasado-- it was published last year;

se habla inglés -- English spoken here

b (impersonal):

aquí se está muy bien -- it’s very nice here; aquí se come muy bien – the food is very good

se iba poco al teatro --people didn’t go to the theater very much;

ya se ha llegado a un punto en que … --we’ve/they’ve now reached a point where …, a

point has now been reached where …;

véase el capítulo X -- see Chapter X;

se los acusa de subversión --they are accused of subversion;

se castigará a los culpables -- those responsible will be punished

c (en normas, instrucciones):

¿cómo se escribe tu nombre? -- how is your name spelled?, how do you spell your name?;

se pica la cebolla bien menuda -- chop the onion finely; sírvase bien frío -- serve chilled

d (reportaje) se dice que ganaron mucha plata… it is said that they made a lot of money

(formal); they are said to have made a lot of money (journalese); I’m told that they (have)

made a lot of money (informal)

17

Translation from Spanish to English

Task 2.1: Examine the uses of ‘se’ printed in bold in the ST and consider what their

contextual communicative effect is. Compare the ST with the TT

De los periódicos e ilustraciones se hacía

más uso; tanto que aquéllos desaparecían

casi todas las noches y los grabados de

mérito eran cuidadosamente arrancados.

Esta cuestión del hurto de periódicos era de

las difíciles que tenían que resolver las

juntas. ¿Qué se hacía? ¿Se les ponía grillete

a los papeles? Los socios arrancaban las

hojas o se llevaban papel y hierro. Se

resolvió última-mente dejar los periódicos

libres, pero ejercer una gran vigilancia. Era

inútil. Don Frutos Redondo, el más rico

americano, no podía dormirse sin leer en la

cama el Imparcial del Casino. Y no había de

trasladar su lecho al gabinete de lectura. Se

llevaba el periódico. Aquellos cinco

céntimos que ahorraba de esta manera, le

sabían a gloria. En cuanto al papel de cartas

que desaparecía también, y era más caro, se

tomó la resolución de dar un pliego, y

gracias, al socio que lo pedía con mucha

necesidad. El conserje había adquirido un

humor de alcalde de presidio en este trato.

Miraba a los socios que leían como a gente

de sospechosa probidad; les guardaba

escasas consideraciones. No siempre que se

le llamaba acudía, y solía negarse a mudar

las plumas oxidadas.

Leopoldo Alas, ‘Clarín’, La

Regenta, edited by Juan Oleza

(Madrid: Cátedra, 1991, vol. 1, pp.

327–8), Cátedra, 1991.

More use was made of newspapers and

illustrated magazines. So much so, that the

former disappeared almost every night and

any prints of merit were carefully torn out of

the latter. The theft of newspapers was one

of the difficult questions to be resolved at

meetings. What was to be done? Chain the

papers up? The members would tear the

pages out or carry off both newspaper and

chain. In the end, it was resolved to leave

the newspapers unfettered, but to exercise

the utmost vigilance. It was to no avail. Don

Frutos Redondo, the richest of the

Americans, could not sleep at night without

first reading the Club’s copy of El Imparcial

in bed. And he was not going to transfer his

bed to the reading room. He took the

newspaper away with him. The five

céntimos which he saved in this way

smacked to him of glory. With regard to the

writing-paper, which also kept disappearing,

and was more expensive, it was resolved to

give one sheet to any member who made an

urgent request for it—and he could consider

himself lucky to get even that. The porter

had acquired the attitude of a prison warder

in these dealings. He regarded members who

were fond of reading as people of dubious

probity, and treated them with scant respect.

He did not always come when he was called,

and he often refused to replace rusty nibs.

Translated by John Rutherford

(Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1984, p.

127), Penguin, 1984.

Contextual information

La Regenta, by Leopoldo Alas, ‘Clarín’, was first published in 1885. The novel is a satirical

exploration of the mores of a dilapidated provincial town. The ST extract is part of an

extended scene set in the Casino, which is the regular meeting place and club of the town

worthies. The TT below is an extract from the Penguin Classics translation of La Regenta by

John Rutherford (1984). Rutherford is a British academic whose area of speciality includes

the works of Alas. His translation has been very well reviewed.

18

Translation from Spanish to English

Task 2.2: Translate the following passage into English.

No he querido saber, pero he sabido que una de las niñas, cuando ya no era niña y no hacía

mucho que había regresado de su viaje de bodas, entró en el cuarto de baño, se puso frente

al espejo, se abrió la blusa, se quitó el sostén y se buscó el corazón con la punta de la

pistola de su propio padre, que estaba en el comedor con parte de la familia. Cuando se oyó

la detonación, el padre no se levantó en seguida, sino que se quedó durante algunos

segundos paralizado con la boca llena, sin atreverse a masticar ni a tragar; por fin se alzó y

corrió hacia el cuarto de baño. Cuando llegó allí lo único que se veía desde la puerta fue los

pies de la suicida. El padre se echó a gritar.

(Adapted from Marías, 1992)

Hervey, S.; Higgins, I. y Haywood L. M. (1995): Thinking Spanish Translation, Londres:

Routledge

19

Translation from Spanish to English

3. Tense, aspect and mood

Task 3.1: The following extract is the beginning of Javier Marías, Corazón tan blanco

translated by Margaret Jull Costa. The Spanish text has been aligned with the translation to

make analysis easier but, in fact, there are no gaps in the original ST. Underline any

translation of tense, aspect or mood that strikes you as interesting. When you have finished,

read the Notes below.

No he querido saber, pero he sabido que una

de las niñas, cuando ya no era niña y no

hacía mucho que había regresado de su viaje

de bodas, entró en el cuarto de baño, se puso

frente al espejo, se abrió la blusa, se quitó el

sostén y se buscó el corazón con la punta de

la pistola de su propio padre, que estaba en

el comedor con parte de la familia y tres

invitados. Cuando se oyó la detonación, unos

cinco minutos después de que la niña

hubiera abandonado la mesa, el padre no se

levantó en seguida, sino que se quedó

durante algunos segundos paralizado con la

boca llena, sin atreverse a masticar ni a

tragar ni menos aún a devolver el bocado al

plato; y cuando por fin se alzó y corrió hacia

el cuarto de baño, los que lo siguieron vieron

cómo mientras descubría el cuerpo

ensangrentado de su hija y se echaba las

manos a la cabeza iba pasando el bocado de

carne de un lado a otro de la boca, sin saber

todavía qué hacer con él.

Llevaba la

servilleta en la mano, y no la soltó hasta que

al cabo de un rato reparó en el sostén tirado

sobre el bidet, y entonces lo cubrió con el

paño que tenía a mano o tenía en la mano y

sus labios habían manchado, como si le diera

más vergüenza la visión de la prenda íntima

que la del cuerpo derribado y semidesnudo

con el que la prenda había estado en contacto

hasta hacía muy poco: el cuerpo sentado a la

mesa o alejándose por el pasillo o también

de pie. Antes, con gesto automático, el padre

había cerrado el grifo del lavabo, el del agua

fría, que estaba abierto con mucha presión.

La hija había estado llorando mientras se

ponía ante el espejo, se abría la blusa, se

quitaba el sostén y se buscaba el corazón,

porque, tendida en el suelo frío del cuarto de

baño enorme, tenía los ojos llenos de

lágrimas, que no se habían visto durante el

I DID NOT WANT to know but I have since

come to know that one of the girls, when

she wasn't a girl anymore and hadn't long

been back from her honeymoon, went into

the bathroom, stood in front of the mirror,

unbuttoned her blouse, took off her bra and

aimed her own father's gun at her heart, her

father at the time was in the dining room

with other members of the family and three

guests. When they heard the shot, some

five minutes after the gift had left the table,

her father didn't get up at once, but stayed

there for a few seconds, paralysed, his

mouth still full of food, not daring to chew or

swallow, far less to spit the food out on to

his plate; and when he finally did get up and

run to the bathroom, those who followed him

noticed that when he discovered the bloodspattered body of his daughter and clutched

his head in his hands, he kept passing the

mouthful of meat from one cheek to the

other, still not knowing what to do with it. He

was carrying his napkin in one hand and he

didn't let go of it until, after a few moments,

he noticed the bra that had been flung into

the bidet and he covered it with the one

piece of cloth that he had to hand or rather

in his hand and which his lips had sullied, as

if he were more ashamed of the sight of her

underwear than of her fallen, half-naked

body with which, until only a short time

before, the article of underwear had been in

contact: the same body that had been sitting

at the table, that had walked down the

corridor, that had stood there. Before that,

with an automatic gesture, the father had

turned off the tap in the basin, the cold tap,

which had been turned full on. His daughter

must have been crying when she stood

before the mirror, unbuttoned her blouse,

took off her bra and felt for her heart with the

gun, because, as she lay stretched out on

the cold floor of the huge bathroom, her

eyes were still full of tears, tears no one had

noticed during lunch and that could not

20

Translation from Spanish to English

almuerzo ni podían haber brotado después de

caer sin vida. En contra de su costumbre y de

la costumbre general, no había echado el

pestillo, lo que hizo pensar al padre (pero

brevemente y sin pensarlo apenas, en cuanto

tragó) que quizá su hija, mientras lloraba,

había estado esperando o deseando que

alguien abriera la puerta y le impidiera hacer

lo que había hecho, no por la fuerza sino con

su mera presencia, por la contemplación de

su desnudez en vida o con una mano en el

hombro. Pero nadie (excepto ella ahora, y

porque ya no era una niña) iba al cuarto de

baño durante el almuerzo. El pecho que no

había sufrido el impacto resultaba bien

visible, maternal y blanco y aún firme, y fue

hacia él hacia donde se dirigieron

instintivamente las primeras miradas, más

que nada para evitar dirigirse al otro, que ya

no existía o era sólo sangre. Hacía muchos

años que el padre no había visto ese pecho,

dejó de verlo cuando se transformó o

empezó a ser maternal, y por eso no sólo se

sintió espantado, sino también turbado. La

otra niña, la hermana, que sí lo había visto

cambiado en su adolescencia y quizá

después, fue la primera en tocarla, y con una

toalla (su propia toalla azul pálido, que era la

que tenía tendencia a coger) se puso a

secarle las lágrimas del rostro mezcladas con

sudor y con agua, ya que antes de que se

cerrara el grifo, el chorro había estado

rebotando contra la loza y habían caído gotas

sobre las mejillas, el pecho blanco y la falda

arrugada de su hermana en el suelo. También

quiso, apresuradamente, secarle la sangre

como si eso pudiera curarla, pero la toalla se

empapó al instante y quedó inservible para

su tarea, también se tiñó. En vez de dejarla

empaparse y cubrir el tórax con ella, la retiró

en seguida al verla tan roja (era su propia

toalla) y la dejó colgada sobre el borde de la

bañera, desde donde goteó. Hablaba, pero lo

único que acertaba a decir era el nombre de

su hermana, y a repetirlo. Uno de los

invitados no pudo evitar mirarse en el espejo

a distancia y atusarse el pelo un segundo, el

tiempo suficiente para notar que la sangre y

el agua (pero no el sudor) habían salpicado

la superficie y por tanto cualquier reflejo que

possibly have welled up once she'd fallen to

the floor dead. Contrary to her custom and

contrary to the general custom, she hadn't

bolted the door, which made her father think

(but only briefly and almost without thinking

it, as he finally managed to swallow) that

perhaps his daughter, while she was crying,

had been expecting, wanting someone to

open the door and to stop her doing what

she'd done, not by force, but by their mere

presence, by looking at her naked, living

body or by placing a hand on her shoulder.

But no one else (apart from her this time,

and because she was no longer a little girl)

went to the bathroom during lunch. The

breast that hadn't taken the full impact of the

blast was clearly visible, maternal and white

and still firm, and everyone instinctively

looked at that breast, more than anything in

order to avoid looking at the other, which no

longer existed or was now nothing but

blood. It had been many years since her

father had seen that breast, not since its

transformation, not since it began to be

maternal, and for that reason, he felt not

only frightened but troubled too. The other

girl, her sister, who had seen the changes

wrought by adolescence and possibly later

too, was the first to touch her, with a towel

(her own pale blue towel, which was the one

she usually picked up), with which she

began to wipe the tears from her sister's

face, tears mingled with sweat and water,

because before the tap had been turned off,

the jet of water had been splashing against

the basin and drops had fallen on to her

sister's face, her white breast, her crumpled

skirt, as she lay on the floor. She also made

hasty attempts to staunch the blood as if

that might make her sister better, but the

towel became immediately drenched and

useless, it too became tainted with blood.

Instead of leaving it to soak up more blood

and to cover her sister's chest, she withdrew

it when she saw how red the towel had

become (it was her own towel after all) and

left it draped over the edge of the bath and it

hung there dripping. She kept talking, but all

she could say, over and over, was her

sister's name. One of the guests couldn't

help glancing at himself in the mirror, from a

distance, and quickly smoothing his hair, it

was just a moment, but time enough for him

to notice that the mirror's surface was also

splashed with blood and water (but not with

21

Translation from Spanish to English

diera, incluido el suyo mientras se miró.

Estaba en el umbral, sin entrar, al igual que

los otros dos invitados, como si pese al

olvido de las reglas sociales en aquel

momento, consideraran que sólo los

miembros de la familia tenían derecho a

cruzarlo. Los tres asomaban la cabeza tan

sólo, el tronco inclinado como adultos

escuchando a niños, sin dar el paso adelante

por asco o respeto, quizá por asco, aunque

uno de ellos era médico (el que se vio en el

espejo) y lo normal habría sido que se

hubiera abierto paso con seguridad y hubiera

examinado el cuerpo de la hija, o al menos,

rodilla en tierra, le hubiera puesto en el

cuello dos dedos. No lo hizo, ni siquiera

cuando el padre, cada vez más pálido e

inestable, se volvió hacia él y, señalando el

cuerpo de su hija, le dijo “Doctor”, en tono

de imploración pero sin ningún énfasis, para

darle la espalda a continuación, sin esperar a

ver si el médico respondía a su llamamiento.

No sólo a él y a los otros les dio la espalda,

sino también a sus hijas, a la viva y a la que

no se atrevía a dar aún por muerta, y, con los

codos sobre el lavabo y las manos

sosteniendo la frente, empezó a vomitar

cuanto había comido, incluido el pedazo de

carne que acababa de tragarse sin masticar.

Su hijo, el hermano, que era bastante más

joven que las dos niñas, se acercó a él, pero a

modo de ayuda sólo logró asirle los faldones

de la chaqueta, como para sujetarlo y que no

se tambaleara con las arcadas, pero para

quienes lo vieron fue más bien un gesto que

buscaba amparo en el momento en que el

padre no se lo podía dar. Se oyó silbar un

poco. El chico de la tienda, que a veces se

retrasaba con el pedido hasta la hora de

comer y estaba descargando sus cajas

cuando sonó la detonación, asomó también

la cabeza silbando, como suelen hacer los

chicos al caminar, pero en seguida se

interrumpió (era de la misma edad que aquel

hijo menor), en cuanto vio unos zapatos de

tacón medio descalzados o que sólo se

habían desprendido de los talones y una

falda algo subida y manchada – unos muslos

sweat) as was anything reflected in it,

including his own face looking back at him.

He was standing on the threshold, like the

other two guests, not daring to go in, as if

despite the abandonment of all social

niceties, they considered that only members

of the family had the right to do so. The

three guests merely peered round the door,

leaning forwards slightly the way adults do

when they speak to children, not going any

further out of distaste or respect, possibly

out of distaste, despite the fact that one of

them (the one who'd looked at himself in the

mirror) was a doctor and the normal thing

would have been for him to step confidently

forward and examine the girl's body or, at

the very least, to kneel down and place two

fingers on the pulse in her neck. He didn't do

so, not even when the father, who was

growing ever paler and more distressed,

turned to him and, pointing to his daughter's

body, said "Doctor" in an imploring but

utterly unemphatic tone, immediately turning

his back on him again, without waiting to

see if the doctor would respond to his

appeal. He turned his back not only on him

and on the others but also on his daughters,

the one still alive and the one he still couldn't

bring himself to believe was dead and, with

his elbows resting on the edge of the sink

and his forehead cupped in his hands, he

began to vomit up everything he'd eaten

including the piece of meat he'd just

swallowed whole without even chewing it.

His son, the girls' brother, who was

considerably younger than the two

daughters, went over to him, but all he could

do to help was to seize the tails of his

father's jacket, as if to hold him down and

keep him steady as he retched, but to those

watching it seemed more as if he were

seeking help from his father at a time when

the latter couldn't give it to him. Someone

could be heard whistling quietly. The boy

from the shop — who sometimes didn't

deliver their order until lunchtime and who,

when the shot was first heard, had been

busily unpacking the boxes he'd brought —

also stuck his head round the door, still

whistling, the way boys often do as they

walk along, but he stopped at once (he was

the same age as the youngest son) when he

saw the pair of low-heeled shoes cast aside

or just half-off at the heel, the skirt hitched

up and stained with blood — her thighs

22

Translation from Spanish to English

manchados –, pues desde su posición era stained too — for from where he was

standing that was all he could see of the

cuanto de la hija caída se alcanzaba a ver.

Como no podía preguntar ni pasar, y nadie le

hacía caso y no sabía si tenía que llevarse

cascos de botellas vacíos, regresó a la cocina

silbando otra vez (pero ahora para disipar el

miedo o aliviar la impresión), suponiendo

que antes o después volvería a aparecer por

allí la doncella, quien normalmente le daba

las instrucciones y no se hallaba ahora en su

zona ni con los del pasillo, a diferencia de la

cocinera, que, como miembro adherido de la

familia, tenía un pie dentro del cuarto de

baño y otro fuera y se limpiaba las manos

con el delantal, o quizá se santiguaba con él.

La doncella, que en el momento del disparo

había soltado sobre la mesa de mármol del

office las fuentes vacías que acababa de

traer, y por eso lo había confundido con su

propio y simultáneo estrépito, había estado

colocando luego en una bandeja, con mucho

tiento y poca mano – mientras el chico

vaciaba sus cajas con ruido también –, la

tarta helada que le habían mandado comprar

aquella mañana por haber invitados; y una

vez lista y montada la tarta, y cuando hubo

calculado que en el comedor habrían

terminado el segundo plato, la había llevado

hasta allí y la había depositado sobre una

mesa en la que, para su desconcierto, aún

había restos de carne y cubiertos y servilletas

soltados de cualquier manera sobre el mantel

y ningún comensal (sólo había un plato

totalmente limpio, como si uno de ellos, la

hija mayor, hubiera comido más rápido y lo

hubiera rebañado además, o bien ni siquiera

se hubiera servido carne). ……

Se dio cuenta entonces de que, corno solía,

había cometido el error de llevar el postre

antes de retirar los platos y poner otros

nuevos, pero no se atrevió a recoger aquéllos

y amontonarlos por si los comensales

ausentes no los daban por finalizados y

querían reanudar (quizá debía haber traído

fruta también). Como tenía ordenado que no

anduviera por la casa durante las comidas y

fallen daughter. As he could neither ask

what had happened nor push his way past,

and since no one took any notice of him and

he had no way of finding out whether or not

there were any empties to be taken back, he

resumed his whistling (this time to dispel his

fear or to lessen the shock) and went back

into the kitchen, assuming that sooner or

later the maid would reappear, the one who

normally gave him his orders and who was

neither where she was supposed to be nor

with the others in the corridor, unlike the

cook, who, being an associate member of

the family, had one foot in the bathroom and

one foot out and was wiping her hands on

her apron or perhaps making the sign of the

cross. The maid who, at the precise moment

when the shot rang out, had been setting

down on the marble table in the scullery the

empty dishes she'd just brought through and

had thus confused the noise of the shot with

the clatter she herself was making, had

since been arranging on another dish, with

enormous care but little skill — the errand

boy meanwhile was making just as much

noise unpacking his boxes — the ice-cream

cake she'd been told to buy that morning

because there would be guests for lunch;

and once the cake was ready and duly

arrayed on the plate, and when she judged

that the people in the dining room would

have finished their second course, she'd

carried it through and placed it on the table

on which, much to her bewilderment, there

were still bits of meat on the plates and

knives and forks and napkins scattered

randomly about the tablecloth, and not a

single guest (there was only one absolutely

clean plate, as if one of them, the eldest

daughter, had eaten more quickly than the

others and had even wiped her plate dean,

or rather hadn't even served herself with any

meat). She realized then that, as usual,

she'd made the mistake of taking in the

dessert before she'd cleared the plates

away and laid new ones, but she didn't dare

collect the dirty ones and pile them up in

case the absent guests hadn't finished with

them and would want to resume their eating

(perhaps she should have brought in some

fruit as well). Since she had orders not to

wander about the house during mealtimes

and to restrict herself to running between

23

Translation from Spanish to English

se limitara a hacer sus recorridos entre la

cocina y el comedor para no importunar ni

distraer la atención, tampoco se atrevió a

unirse al murmullo del grupo agrupado a la

puerta del cuarto de baño por no sabía aún

qué motivo, sino que se quedó esperando, las

manos a la espalda y la espalda contra el

aparador, mirando con aprensión la tarta que

acababa de dejar en el centro de la mesa

desierta y preguntándose si no debería

devolverla a la nevera al instante, dado el

calor.

Javier Marías, Corazón tan blanco

the kitchen and the dining room so as not to

bother or distract anyone, she didn't dare

join in the murmured conversation of the

group gathered round the bathroom door,

why they were there she still didn't know,

and so she stood and waited, her hands

behind her back and her back against the

sideboard, looking anxiously at the cake

she'd just left in the centre of the abandoned

table and wondering if, given the heat, she

shouldn't instead return it immediately to the

fridge

A Heart so White by Javier

Marías translated by Margaret Jull

Costa

.

Notes on syntactical and discourse issues arising from the translation of the extract from

Corazón tan blanco (Please note that the line numbers do not coincide with the texts above.)

1-2. Length and complexity of sentences, and preference for hypotaxis or parataxis

The first part of the ST (lines 1-23, 298 words) consists of 4 sentences, each containing at

least one subordinate clause. The second part (ST23-38, 161 words) comprises one long

sentence containing a number of subordinate clauses. In each part, there is a pause that could

have been punctuated with a full stop but is instead marked by a semicolon followed by ‘y’

(ST9-10 and 27), indicating continuity of sense and intonation. After the brisk, stark matterof-factness of the series of coordinated clauses in the first sentence (‘entró..., se puso..., se

abrió..., se quitó... y se buscó’), the effect of the remainder of the novel’s lengthy opening

paragraph (including the four pages omitted from the ST) is to slow down the action

drastically, and meticulously highlight incongruous details of various characters’ reactions

to the gunshot. Syntactical structures are deliberately extended, delayed and elaborated to

produce the stylized slow-motion effect. This is particularly marked in the second section of

the ST, in which each of the main elements of the sentence (‘la doncella ... había estado

colocando ... la tarta helada ... la había llevado hasta allí y la había depositado sobre una

mesa ...’) is qualified and expanded to a degree that impatient readers may find irritating, yet

without at any point losing syntactical cohesion or logical cogency.

In general, the TT carefully matches the length and complexity of the sentences, using the

same punctuation as the ST except for slight variation in the use of commas. There is one

clear example of a hypotactic ST structure being replaced by a paratactic one in the TT: ‘se

buscó el corazón con la punta de la pistola de su propio padre, que estaba en el comedor’

(ST4-5) > ‘aimed her own father’s gun at her heart, her father at the time was in the dining

room’ (TT4-5). This asyndetic construction in place of a relative clause is a conspicuous

departure from a translation strategy generally based on closely reproducing the hypotactic

nature of the ST, and the repetition of ‘her father’ is rather clumsy. The transposition is an

understandable result of the change of word order produced by the idiomatic rendering of

the first clause, but it would be possible to arrange the sentence in such a way as to have ‘her

24

Translation from Spanish to English

father’ at the end of the main clause followed by a relative clause (‘who was in the dining

room’).

By reproducing the discourse structure of the ST so closely, the translator has risked

creating a style that is more likely to be regarded as contrived, over-formal or even awkward

by TL readers than the style of the ST would be perceived by SL readers. However, there

are places where the TT wisely sacrifices some of the density and concision of the ST in

order to achieve a more communicative flow by means of expansion: ‘el cuerpo sentado o

alejándose por el pasillo o también de pie’ (ST19-20) > ‘the same body that had been sitting

at the table, that had walked down the corridor, that had stood there’ (TT20-21); ‘su propio y

simultáneo estrépito’ (ST24) > ‘the clatter she herself was making’ (TT26); ‘por haber

invitados’ (ST27) > ‘because there would be guests for lunch’ (TT29-30). The overall

carefulness and formality of social register indicated by the sentence structuring is also

markedly offset by the use of contractions, introducing a more informal style suggestive of

oral discourse: ‘wasn’t a girl ... hadn’t long been ... didn’t let go ... she’d just brought ...

she’d been told ... she’d carried ... hadn’t even served.’ Not all the opportunities for

contraction are taken up, though: ‘I did not want to know but I have since come to know ...

there would be guests ... would have finished.’

3. Flexibility of word order

The ST provides no examples of manipulation of word order for emphatic or tonal effect. Its

tendency to keep to unsurprising subject-verb-object sequences contributes to the overall

effect of careful, dispassionate dissection of the suicide and its aftermath.

The translator’s decision to transpose ‘Cuando se oyó la detonación’ (ST6) into ‘When they

heard the shot’ (TT6) — rather than the more obvious passive (‘When the shot was heard’)

— has the virtue of retaining the same word order, in line with the general strategy of

imitating the sentence structures of the ST.

5. Positioning of adjectives

The ST is sparing in its use of adjectives, since the focus is primarily on the narration of

actions and reactions. Most of the adjectives used are doing a straightforward defining job

and are therefore postpositioned and unmarked: ‘prenda íntima’ (ST17), ‘gesto automático’

(ST20), ‘fuentes vacías’ (ST23). In contrast, the phrase ‘su propio y simultáneo estrépito’

(ST24) draws attention to itself because of the positioning of both adjectives before the noun

(rather than ‘su propio estrépito simultáneo’), an effect compounded by the number of

syllables in ‘simultáneo’ and the contrived juxtaposition of two esdrújula words. The TT

reproduces the sense accurately and fluently (though leaving the notion of simultaneity

implicit), but does so in a more idiomatically normal way, without conveying any of the

stylistic peculiarity of the ST construction.

6. Use of nouns as attributive adjectives

The TT contains two more or less obligatory transpositions of this kind: ‘mesa de mármol’

(ST22-3) > ‘marble table’ (TT24) and ‘tarta helada’ (ST26) > ‘ice-cream cake’

TT29). The expansion of ‘chico’ (ST26) into ‘errand boy’ (TT27-8) is justified not only on

the grounds of clarification but also because the availability of compound nouns of this kind

in English means that speakers are likely to specify barman, shop girl, chambermaid,

cleaning lady or delivery boy where Spanish speakers may use a vaguer one-word term such

as chico/a, mozo/a or doncella.

25

Translation from Spanish to English

9. Markers of possession

The first part of the ST features a number of phrases in which possession (especially of

clothing and parts of the body) is indicated without an explicit possessive adjective: ‘se

abrió la blusa, se quitó el sostén y se buscó el corazón’ (ST3-4); ‘el padre ... la boca ... al

plato’ (ST7-9), and so on. These are sensibly translated with possessive adjectives:

‘unbuttoned her blouse, took off her bra and aimed ... at her heart’ (TT4-5); ‘her father

... his mouth ... on to his plate’ (TT7-9). In the case of ‘la prenda íntima’ and ‘del cuerpo

derribado y semidesnudo con el que la prenda había estado en contacto’ (ST17), on the other

hand, it is not so obvious that the possessives used in the translation (TT18) are

desirable. Here, the impersonality of ‘the underwear’ and ‘the fallen, half-naked body’

might be more in keeping with the stylistic effect of distancing that is created at this point in

the ST (the body is increasingly being treated as an object dissociated from the personality

of the daughter).

10. Omission of subject pronouns

In one or two of the places in which the ST avoids ambiguity by specifying the subject of a

verb with a noun phrase (‘la niña hubiera abandonado’ ST6, ‘el padre había cerrado’ ST20),

it would be possible, and perhaps more elegant, to achieve the same objective in English

with subject pronouns (‘she ... he’).

13. Use of ethic datives

The more oblique or surprising ethic datives tend to occur in types of discourse that are

more colloquial or spontaneous than the tightly controlled literary language employed here

by Marías. The ethic datives that do appear in the ST perform the common function of

marking possession and are translated with possessive adjectives, as noted above (see

section 9): ‘se abrió la blusa, se quitó el sostén y se buscó el corazón’ (ST3-4); ‘se echaba

las manos a la cabeza’ (ST12).

15. Variation in the form of adverbs

In line with normal usage in English, the TT shows minimal variation in the form of

adverbs, in contrast to the ST: ‘por fin’ (ST10) > ‘finally’ (TT10); ‘de cualquier

manera’ (ST31) > ‘randomly’ (TT34); ‘totalmente limpio’ (ST32) > ‘absolutely clean’

(TT35); ‘más rápido’ (ST33) > ‘more quickly’ (TT36). ‘Con mucho tiento y poca

mano’ (ST25) could also have been rendered with two ‘-ly’ adverbs, but the choice of ‘with

enormous care but little skill’ (TT27) has the valuable, slightly exoticizing effect of echoing

a distinctive feature of the ST’s style.

16. Range of tenses available

The ST sets up a complex set of relationships between three different points in time: a

narrative present in relation to which ‘he sabido’ is a recent occurrence; the suicide and

its aftermath, narrated in the past; and events and situations before and after the gunshot,

referred to in the pluperfect. Consequently, the text uses an unusually wide range of tenses:

perfect, preterite, imperfect, imperfect subjunctive, conditional perfect, pluperfect,

pluperfect subjunctive, and even the past anterior. Some of these are

unproblematically matched by corresponding tenses in the TT, but there are two places in

the ST where nuances conveyed by specific tense forms are difficult to capture in the TL.

Firstly, the perfect tense in ‘No he querido saber, pero he sabido’ (ST1). This provides a

striking opening for the novel, generating a slightly unsettling sense of temporal uncertainty

or complexity from the outset. ‘No he querido’ is not the same as ‘no quise’ or ‘no quería’,

26

Translation from Spanish to English

both of which are clearly past and could both be translated with the form used in the TT, ‘I

did not want to know’. In both Spanish and English, the perfect implies a link to the present

time in which the utterance is made: ‘ha salido’ and ‘she’s gone out’ imply ‘she’s not here

now’. In Spain, the perfect is sometimes also used to refer to very recent events that would

not be expressed with a perfect in English: for example, asking someone who has just tasted

something ‘¿Te ha gustado?’ > ‘Did you like it?’ (in most of Latin America, people would

tend to ask ‘¿Te gustó?’ in the same situation). The translator has recognized that English

speakers, especially in North America, are less likely to say something like ‘I haven’t

wanted to know’ (except perhaps in expressions such as ‘I’ve never wanted to know’) than

Spaniards are to say ‘no he querido saber’, but has wisely retained the perfect tense in the

second clause and reinforced its effect by the addition of ‘since’. While the loss of aspectual

precision in ‘did not want to’ may be justified by the general vagueness of the English tense

system in comparison with Spanish, alternative renderings that retain more of the specificity

of the ST phrase would be worth considering (especially for a British readership), for

example: ‘I’ve been anxious not to know, but I’ve come to know all the same.’

The second instance of a tricky tense in the ST is ‘cuando hubo calculado que en el comedor

habrían terminado el segundo plato’ (ST28). Once again, Marías is very precise in his use of

tenses and this precision is lost in the TT: ‘when she judged that...’ (TT31). Within the

sequence of events expressed in the pluperfect, the past anterior indicates an action

immediately followed by another (‘la había llevado hasta allí’), suggesting a degree of

exactness in the maid’s calculations — she may be clumsy but she knows how long they

usually take to eat each course. More radical transposition may help to convey the effect in a

different way: ‘Having prepared the cake and laid it out on the dish, and having worked out

exactly when the diners would have finished the second course.’

17. Marking of perfective/imperfective aspect

The ST distinguishes clearly between perfective actions (‘se puso ... se abrió ... se quitó

... se buscó ... se oyó ... se alzó ... corrió’ are instantaneous, and ‘se quedó’ is continuous but

explicitly limited in duration) and imperfective ones (‘era ... hacía ... estaba ...