Chem 1721 Brief Notes: Chapter 20 Chapter 20: Nuclear Chemistry

advertisement

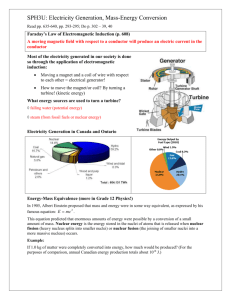

Chem 1721 Brief Notes: Chapter 20 Chapter 20: Nuclear Chemistry nuclear reactions vs. “typical” chemical reactions types of radioactive decay; writing balanced nuclear reactions (and predicting products) nuclear stability and the n:p ratio kinetics of nuclear decay fission vs. fusion the differences between nuclear reactions and chemical reactions: 1. chemical reaction: break and form bonds between atoms but elements remain the same – nuclei are unchanged nuclear reaction: changes in the nucleus of atoms frequently resulting in transformation to new elements 2. different isotopes of an element typically have about the same reactivity in a chemical reaction but very different reactivity in a nuclear reaction 3. rate of a nuclear reaction is not affected by T, P, or addition of a catalyst 4. energy considerations ⎯ much larger quantities of energy associated with nuclear change ex. combustion of 1.0 g of CH4: CH4 (g) + 2 O2 (g) CO2 (g) + 2 H2O (g) releases 56 kJ of energy nuclear transformation of 1.0 g 235U releases 8.2 x 107 kJ of energy quick review of atomic structure: subatomic particles common to the internal structure of all atoms include protons (p), neutrons (n), & electrons (e ) ⎯ particle proton, p neutron, n electron, e ⎯ mass 1.67 x 10 27 kg 1.67 x 10 27 kg 9.11 x 10 31 kg ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ charge +1 0 ⎯1 protons and neutrons are in the nucleus – called the nucleons the nucleus is the center of mass and positive charge (holds the heavier and positively charged particles) the nucleus is very small (imagine a fly on the 50-yard line of a football field; the fly is the nucleus, the field is the atom) an atom is mostly empty space electrons are outside of the nucleus in orbitals with specific energy, shape, orientation relative number of protons and electrons determines the charge of the species if #p = #e the atom is neutral ⎯ if #p > #e the ion is negatively charged (i.e. an anion) ⎯ if #p < #e the ionis positively charged (i.e. a cation) ⎯ ion formation occurs with the loss or gain of electrons an atom of an element is identified by its atomic number and mass number atomic number = # protons in the nucleus; this does not change for atoms of a specific element i.e. every atom of calcium has 20 protons in the nucleus if the number of protons changes the identity of the element changes mass number = # protons + # neutrons; mass number can change because the number of neutrons can be variable i.e. an atom of calcium – 42 (42Ca) has 20 protons + 22 neutrons in the nucleus vs. an atom of calcium – 44 (44Ca) has 20 protons + 24 neutrons in the nucleus isotopes: atoms with the same number of protons (∴ same atomic number, same element) but different number of neutrons (∴ different mass number) are isotopes of one another ex. 42 Ca vs 44Ca note: isotope nomenclature involves naming the element and indicating the mass number i.e. calcium – 42 or calcium – 44 isotope symbols show the mass number superscripted in front of the element symbol; may or may not be combined with the atomic number subscripted in front of element symbol i.e. 42 Ca, or 4420Ca the nucleus of a specific isotope is called a nuclide Nuclear Reactions: Radioactive Decay Processes scientists have known since 1896 that many nuclides are radioactive – they spontaneously decay and emit radiation there are 4 common emission processes + electron capture 1. alpha emission, α, 42He an alpha particle is a helium nucleus: 2 p, 2 n, 0 e⎯ alpha particles are positively charged α-emission is common for heavier radioactive isotopes ex. 238 U 92 234 Th + 42He OR 238 90 U 92 234 Th + α 90 note: a balanced nuclear equation demonstrates conservation of atomic number and mass number i.e. Σmass # left = Σmass # right and Σatomic # left = Σatomic # right mass #: 238 = 234 + 4 atomic #: 92 = 90 + 2 note: we are not concerned with charge considerations in nuclear reactions because they do not affect the reactivity or the transformation products i.e. 2. 4 2 He NOT 4 2 He2+ beta emission, β, 0 1e ⎯ a beta particle is an electron: 0 p, 0 n beta emission occurs when a neutron is converted to a proton and an electron (emitted from nucleus) n p + e ; note: a new proton is formed ∴ the atomic number increases by 1 ⎯ ex. 3. 131 I 13154Xe + 0 1e 53 ⎯ 131 OR I 13154Xe + β 53 positron emission, β+, 01e a positron has the same mass as an electron, but is positively charged: 0 p, 0 n positron emission occurs when a proton is converted to a neutron and a positron (emitted from nucleus) p n + β+; note: a proton is lost ∴ the atomic number decreases by 1 ex. 4. 40 K 4018Ar + 01e 19 OR 40 K 4018Ar + β+ 19 gamma emission, γ, 00γ gamma emission has no mass and is not affected by magnetic or electric fields (no charge characteristics) gamma emission is electromagnetic radiation of high energy, short wavelength (λ = 10 11 to 10 14 m) stream of high energy particles; emission frequently accompanies other emission processes as a mechanism of energy release ⎯ ⎯ gamma emission is often not included in nuclear equations because it doesn’t change mass or atomic number 5. electron capture occurs when the nucleus “captures” an inner-shell electron 0 1e + p n; note: a proton is lost ∴ the atomic number decreases by 1 ⎯ 197 ex. Hg + 0 1e 19779Au 80 ⎯ Summary: process α - emission β - emission β+ - emission γ - emission electron capture symbol α, 42He β, 0 1e β+, 01e γ, 00γ 1e as reactant ⎯ 0 ⎯ Δ atomic number (Δ#p) ⎯2 +1 ⎯1 0 ⎯1 Δ mass number ⎯4 0 0 0 0 Δ#n ⎯2 ⎯1 +1 0 +1 some examples: ex. write the balanced nuclear equation describing α - emission from curium-242: 242 ex. Cm 96 4 2 He + _________ 238 answer: 28 0 1 ⎯ e + 28 Al 13 Th 90 210 Ra + _________ answer: α - emission 88 Nuclear Stability nuclear stability defined in terms of a measurable (or not) half-life (t1/2) Why do some but not all nuclei decay radioactively? Why do some decay by α-emission and other β-emission? nuclear stability is related to the n:p ratio in the nucleus; neutrons are the “glue” holding the nucleus together band of nuclear stability number of neutrons Mg 12 What type of decay occurs with the transformation of thorium-214 to radium-210? 214 1:1 neutron:proton ratio number of protons the higher the # of protons, more neutrons required for a stable nucleus; minimize p – p repulsions Pu 94 write the balanced nuclear equation describing β - emission that forms aluminum-28: _________ ex. answer: can use the n:p ratio to help predict more or less likely decay processes high n:p tend to decay by β-emission (n p + β so n:p ratio decreases) low n:p tend to decay by α, β+, or electron capture (p n + β+ or e + p n so n:p ratio increases) ⎯ kinetics of nuclear decay nuclear decay processes follow 1st order kinetics rate ∝ [ ], OR rate ∝ N where N = number of radioactive nuclei in the sample rate law: rate = kN rate = decay rate, k = decay constant with units t 1, N = # of radioactive nuclei ⎯ ln(N/N0) = ⎯kt and t1/2 = 0.693/k note: 1st order kinetics so the half-life is constant ex. 32 P is a radioisotope used in the treatment of some forms of leukemia. What % of radioactive nuclei remain after 35.0 days? For 32P, t1/2 = 14.28 d. answer: k = 0.0485 d 1; 18.3% remain after 35 days ⎯ Fission vs. Fusion heavy nuclei gain stability when they fragment into midweight elements and release energy; FISSION light nuclei gain stability when they fuse together and release energy: FUSION fission – more detail usually initiated by some sort of bombardment, i.e. neutrons hitting 235U fission doesn’t occur exactly the same way each time can get a series of fragmentation steps – decay process i.e. 1 0 n + 23592U 91 Kr + 14256Ba + 3 10n 36 result: a chain reaction that can continue with external supply of neutrons amount of material required to get a self-sustained chain reaction is the critical mass ex. controlled nuclear fission is the process in nuclear reactors and power plants control rods absorb and regulate neutron flow U fuel in containment vessel surrounded by coolant energy released by fission heats coolant steam drives turbine electricity fusion – more detail occurs in the upper atmosphere and outer space; reactions that power the sun and stars 1 1 3 3 1 H + 11H 21H + 01e 1 H + 21H 32He 2 He + 32He 42He + 2 11H 2 He + 11H 42He + 01e ex. fusion is attractive as a potential alternative power source H isotope fuel is cheap and plentiful; reaction products are nonradioactive and nonpolluting; “cold fusion” BIG area of research temperature of 40 billion K required to initiate fusion