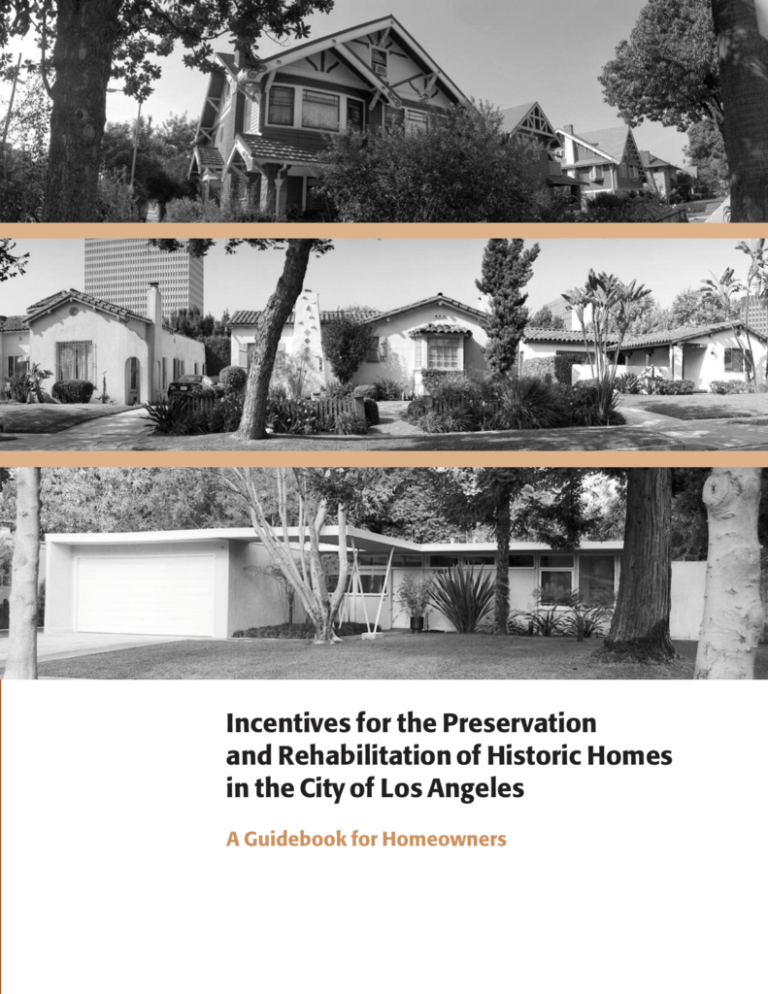

Incentives for the Preservation and Rehabilitation of Historic Homes

advertisement