To Talk or not to Talk

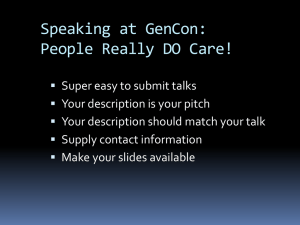

advertisement

To Talk or not to Talk Tactical Communication and Behaviour in Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games by Clas Olson Master Programme in Game Design School of Engineering Blekinge Institute of Technology Karlshamn, Sweden 2009-03-28 To Talk or not to Talk: Tactical Communication and Behaviour in MMORPGs Abstract This study is about finding out whether it is more efficient in combat in MMORPGs (Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games) to use your voice for communication than the text chat function that is usually provided by the game, and my hypothesis was that it is so. Test players have been brought in to play an instance in WORLD OF WARCRAFT twice under different communication conditions. The result was that even with an experienced team of players that have worked together for several months, though there is not much communication between them, it can still lead to failure and bad performance in combat if the only way to communicate is through text. Since this is the only way of communication provided in the game itself (other than the even slower mail system), it is assumed that the developer thinks that voice communication is not essential enough to the game to be provided, which this study says is incorrect. The behaviour of the players have also been analysed, and behavioral schema types have been constructed to visualise the standard behaviour of player playing different roles in MMORPGs. Keywords: World of Warcraft, MMORPG, multiplayer games, Ventrilo, communication, chat, voice, schemas, combat. 2 Clas Olson Table of Contents Introduction 4 Background 4 Related Work 4 The Game 4 Goals and Basic Game Play 5 The Experiments 5 Information Gathering 5 Obstacles 6 Learning from Mistakes 6 The Purpose and Use of the Experiments 6 Analysis 7 Definitions 7 Method 7 Variables 8 Kinds of Communication 9 Results 11 Roles, Training, and Professionalism 11 Combat Schemas 13 The purposes of text versus voice communication 16 Why does not everyone use voice? 18 The importance of communicating in combat 18 Conclusion 19 Future Studies 19 References 20 Appendix A: Experiment Design 23 Appendix B: Transcriptions 29 Appendix C: Timelines 31 3 To Talk or not to Talk: Tactical Communication and Behaviour in MMORPGs Introduction The intention of this study was to shine a light on the fact that in order to be efficient in combat, you have to communicate via your voice, and not through the only means of communication that usually is provided in an MMORPG (Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game), a text chat. It also includes a description of likely behavioral schemas (that is, thought patterns and methods) of individuals and parties in combat. Since an important part of such a game is spent in combat, and the preferred way to do combat is together in small groups, communication is very important in this kind of game. More effort should then be placed on the developer’s part to facilitate easier and more efficient combat communication. Due to a lack of experimental data (see Obstacles, under The Experiments) the statistical value of this report is less than it could be. It should be perceived as an exploratory study, and something that should be continued upon in the future. Background The study was part of a 10-week project in the Masters Programme for Game Design on Blekinge Institute of Technology. I have often seen that mistakes are made in co-operative games, not only computer games, that have their source in lack of or misunderstood communication. This is in most ways not limited to playing games, but it is easily explored there, and the fact that players of multiplayer games can often be located in disparate locations of the world make the efficient use of communication via voice or text extremely important for success in games. Related Work Few, if any, other works have been published about the need or importance of communication in games, though there have been several texts concerning digital communication in general (for example [1 and 13]) and for military applications[2]. ”Alone Together”[7] is related to the subject of WORLD OF WARCRAFT, but is largely a mathematical study, and does not bring up communication specifically, and not tactical communication, that is communication in or related to combat, at all. About MMOGs (not necessarily roleplaying games) in general, there are a large amount of studies, which is understandable considering their popularity. Most of them are centred around game design[13-18], economics[19-22], or psycho-social studies[23-37]. There is however, in my opinion, a great need for these kinds of evaluations, since the whole purpose of playing computer games online is to either compete or co-operate toward a common goal, and the means to do that is through communication. The Game As a massively multiplayer online game, WORLD OF WARCRAFT enables thousands of players to come together online and battle against the world and each other. Players from across the globe can leave the real world behind and undertake grand quests and heroic exploits in a land of fantastic adventure. WORLD OF WARCRAFT (commonly acronymed as WOW) is a massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG). It is Blizzard Entertainment's fourth released game set in the fantasy Warcraft universe, which was first introduced by WARCRAFT: ORCS & HUMANS in 1994. WORLD OF WARCRAFT takes place within the world of Azeroth, four years after the events at the conclusion of Blizzard's previous release, WARCRAFT III: THE FROZEN THRONE. Blizzard Entertainment announced WORLD OF WARCRAFT on September 2, 2001. The game was released on November 23, 2004, celebrating the 10th anniversary of the Warcraft franchise. 4 Clas Olson The first expansion set of the game, THE BURNING CRUSADE, was released on January 16, 2007. On August 3, 2007, during the 2007 BlizzCon event, Blizzard announced a second expansion set, WRATH OF THE LICH KING, which was released on November 13, 2008. With more than 11 million monthly subscribers, WORLD OF WARCRAFT is currently the world's largest MMORPG in those terms, and holds the Guinness World Record for the most popular MMORPG. In April 2008, WORLD OF WARCRAFT was estimated to hold 62% of the massively multiplayer online game (MMOG) market. Goals and Basic Game Play The goal of the game is based upon each player’s preferences. If the player is interested in player versus player combat, or PvP for short, he or she may focus on this part of the game. But if the player is more interested in co-operation and to overcome the challenges the game designers have created, also known as player versus environment or PvE, he or she may instead spend more time in different dungeons and specific group-challenges where five or more players have to communicate and co-operate to overcome each challenge they face together. There are three archetypes of characters in WORLD OF WARCRAFT; the Tank is the damage-taker and will ideally be the one targeted and damaged by enemy AI. The Damage Dealer is as it states a character that does damage to enemies while the Tank keeps the enemy’s or enemies’ attention. Lastly is the Healer who, as stated earlier, can give the Tank health back at the expense of mana. There are many other features in WORLD OF WARCRAFT, but it is only player versus player combat and player versus environment combat that is of main interest since the game is a Role playing game where players have to battle and kill enemies to gain experience and to level-up. Many people are interested in role playing as well, but in the end they usually have to fight monsters to level up and gain a higher status among the other role players. The Experiments The experiments are the most vital part around which this study has been based, and the main provider of information, but they were also the main source of problems in the project. In the texts the word ”instance” is used, as the place where the experiments are performed. In instance is an area in WORLD OF WARCRAFT which is isolated from the rest of the world. When a party enters an instance a unique copy of that area is created, in which only the members of the party and no other can enter. If someone else would enter the portal that is the entrance to the instance, a separate copy of the instance would be created. There are at the time of writing over 80 different instances, some of which are only available to one the different factions (Horde and Alliance). Information Gathering The analysis of the importance of communication with others in MMORPGs have been done by recording several play sessions of the game WORLD OF WARCRAFT (henceforth called WoW) by Blizzard Entertainment[3]. More information about that game can be found in Appendix A: The Experiment Design. The players have communicated by voice using the program Ventrilo[4], and these communications, where they occurred, have been recorded and later analysed. I have also had the participants answered questions at the end of each play session about their opinions of the different kinds of communication (text chat and voice), and how they thought these affected their play. More information about the experimental procedures can be found in Appendix A. 5 To Talk or not to Talk: Tactical Communication and Behaviour in MMORPGs Obstacles The main obstacle during this entire project has first been to get participants to do the experiments. Previous experience in earlier experiments in the master programme (which only has four students) has been that it is very hard to acquire participants in the environment I am currently working in. The second obstacle has been the need for individual convenience among the participants. Not only has the experience of few participants been mine, but also among the staff at the GAMALab (Game And Media Arts Laboratory) before the programme started, so I could draw upon their knowledge when trying to get participants. Netport Karlshamn were involved to provide funding for incentives, which had worked in previous experiments at the Lab, and a wide call for participant was made to all the students at Blekinge Institute of Technology, as well as on a junior high and high school in Karlshamn. Later in the project I also put up posts on two Swedish internet forums for WoW players, worldofwar.se and warcraftguide.se. The fact that WoW is a game and almost always played for fun, makes most people not want to play more than one session in the same instance, if they are not interested in the scientific procedures behind the experiment themselves. They much rather play an instance once, and then go on to some more enjoying endeavour, inside or outside the game. The second obstacle was caused by the inherent structure of WoW. When you first create a character, you choose which of Blizzard’s WoW-servers to place the character on. That character can then only interact with other character on that server, not with any other. There are at time of writing over 260 servers only in Europe, containing many thousands of players each, and as the player base increases the number of servers also increases. This means that it will probably be very difficult to acquire two random participants that happens to play on the same server with compatible allegiances and levels of experience, which is a requirement for doing the same instance which is challenging. I were therefore forced to let the participants find their own groups and parties in which they could do the experiments in, which increased my dependency on them and my ability to work within the time constraints. On the other hand, it removed the need for me to acquire 50 participants for the ten experiments that I preferred to make, and it also removed some administrative pressure. Learning from Mistakes In hindsight, the main problem to getting enough participants was probably the structure and strictness. Based upon response and critique from those potential participants who actually did not perform the experiments, future experiments of this kind probably need to be a bit different. Since WoW is a game intended only for entertainment, and most players do indeed play it in that way, putting as many constraints on the play as I have done can be very unattractive. And since all potential participants only need to play at their own convenience, that is there is no obligation at all to participate, the need to perform two instances immediately after one another, though it provides good data, is something that few people would do for entertainment. One could get good data from experiments with only one experiment, using the same experimental design and only one set of questions after the session, though one would lack the clear comparison between the two almost identical session. But if one then would get many more experiments, one could normalise and adapt the results to take into account the different instances, different players, and different equipment. The Purpose and Use of the Experiments This study uses both qualitative and quantitative data. Quantitative data is derived from the measurements by objective instruments, such as, in my case, the time stamp from the recording of the video in order to ascertain whether one battle is more efficient than 6 Clas Olson another. Qualitative data is collected from subjective data, such as the answers of questions. Both of these kinds of data has their merits, and to get the best information out of a study, a combination of both is best used. Practical information about what people actually do in an MMORPG (as opposed to just asking people questions) is probably the best way to get high quality, and qualitative, information, and people might not actually remember every detail about a play session afterward, when asked about it. But probably the best method to use is to get both qualitative and quantitative data, as I do when I record video and audio from the sessions and ask the players questions afterward with an online survey. The experiments are performed in an instance in the game (see Appendix A for an explanation of instance). This means that the environment is very controlled; no other players in the game can come and disturb the players or the results of the experiments, and the sessions will have a definite start and end. Instances are also a very common way to spend your time in WoW, especially among the more experienced players questing for special items that can only be acquired in that specific instance. The experiments have been designed to have two sessions under different conditions, either allowing communication using voice, text chat, or no communication at all. The last condition is used as a control to determine weather success in combat requires communication in any complex manner at all. In a previous experiment very little communication were needed, as the members of the party already knew their roles in combat (they were what Björk et al.[2] call ”experts”), and thus there are expectations on what each party member is supposed to do in combat. The conditions among the different experiments will be as randomised as possible, so that the order of the conditions does not affect the result of the experiments. Analysis The purpose of this study has been to find out weather it is more effective in combat in an MMORPG to communicate with your party members using voice, as opposed to any other kind of communication. To find out if this is true or not, you need a good definition of what good combat performance is, and you need good methods to gather the information from the gaming sessions. Definitions For the purposes of this study, the definition of efficiency in combat has been the time it takes to defeat each boss in the instance, the time to finish the instance as a whole, if some of the party members died in the instance, and if the party failed in a boss fight, and had to start it over. The less time it takes to do the battles and finish the instance, the more efficient it is judged to be. The times and the possible amounts of deaths in the party are compared between the two sessions that each party plays. The two sessions are played by the same party members and players, with the same equipment, and in the same instance, so they are comparable. The time of the individual boss fights are usually better to compare than the duration of the whole instance, since there may be several pauses which are not related to the game itself, such as players leaving their keyboards or checking over their skills at the request of someone outside of the instance. Method To come up with results I will listen to the conversations during sessions with voice communication, as well as read the conversation in tests with text communication only, and correlate those conversations to the events that are currently happening in the game. 7 To Talk or not to Talk: Tactical Communication and Behaviour in MMORPGs The questionnaires are then used to understand the opinions of the players, and how they perceived the different styles of play. The questionnaires can be read in the end of Appendix A. The method which I will use to analyse the material that comes from the experiments is partly derived from COMMUNICATION IN EXPERT TEAMS[2], Fig. 1: The text chat window though that method will be adapted to better fit the needs of an MMORPG and not a pure military application. That method is also largely focused on words and manner in the communication itself, and not its effectiveness in a specific application. This will more be the purpose of my methods on analysis. As time is a good definition of effectiveness in combat, especially when comparing two sessions whose only difference is the communication conditions, this has been the main focus when developing methods for analysis. The video material of each session will be recorded to an avi file, and thus it is easy to know at which time different events happen, and thus easy to measure the time it takes for a party to defeat a certain boss, or finish the instance. The boss fight times and times to full completion of the instance will be placed into a timeline, and the two timelines from the two game sessions will be compared to each other, to see the differences. Since there is a tendency to be more efficient the second time one plays through the same instance, especially if the instance is new to you (you then know the abilities of the bosses and which way to go in the sometimes labyrinthine paths of the instance), that has to be taken into account when analysing the data. This is also why the experiment are as varied as possible, for example one group may play their first session using only text communication, and the second with only voice communication, while another group will play their sessions the other way around, forts voice then text. This eliminates some of the effects of learning the instance for the second play through, but it still has to be taken into account. Variables WoW players differ from each other in many ways, and almost no two characters or players behave in the same way. There are therefore many variables to be taken into account when analysing the data, and most of them are listed here. • • • • • • • • Player experience with WoW Player experience with voice communication in games Player age Character level Character equipment Character talents Computer performance Computer Internet connection Most of these variables are revealed in the questionnaire which is filled in between the play sessions, except for the equipment that the character carries, but that would be too complex a subject to bring up, as equipment is the most extensive variation of a WoW character. Several pages would be needed to list each of a characters items, and they are not deemed as important for the performance and efficiency of the players in the instance as communication and the players actually performing their respective roles. The players’ 8 Clas Olson levels are not answered in the questions, but can be seen in the interface in the video recording. The performance and Internet connection of the various participants’ computers are variables that not only lies out of my control, but in the case of the latter also outside of the control of the player. Concerning the former, all players are assumed to have computers that correspond to the minimum system requirements, as stated in Appendix A. If there are reports of connection or performance problems during the sessions, it will be taken into account, if the problems affect the performance of the party. Kinds of Communication Just as is described by Björk et al.[2], there are different kinds of messages in WoW, and here are some of them listed, with their purposes in the game.The categories are not exactly similar to those mentioned by Björk et al. but their purposes meanings are the same. • Information about tactics The sender, usually the leader of the party, gives information about how the party is going to perform. This can be before the party enters the instance, and is then usually about general tactics and procedures. Information can also come immediately before battle, and then it is usually about special tactics in this specific battle. Example: P1: “Well, we just go as usual, then?” This simple statement by the group leader is enough so that everyone will know what to do, no new procedures or tactics is to be implemented during the instance. It was stated in the immediate start if the instance. • Information about the enemy’s abilities The sender, usually the leader of the party or the one most knowledgeable of the instance, gives information of the capabilities of the enemy. This can be any special abilities or spells, but also how the enemy tends to move and choose targets, or if it is particularly tough or has special sensitivities. Example: P1: “Does anyone remember what this guy did?” P2: “Yeah, he started to fire lightning over a large area, and then there was some sort of laser beam thing that followed us and that we should stay away from.” P1: “OK, let’s go then.” • Information about the player’s abilities The Sender informs the other members of the party about how one or more of the sender’s abilities work and how it affects the battle, usually in the response of a question. Example: P1: ”How about these dragons, are there any difference between them?” P2: ”Yeah, later they will get some special abilities, but this one is a Tank, that one is a DPS, and that one over there is a Healer.” A more experienced player explains the abilities of some dragons that the players will ride upon and use throughout the instance. • Information about map layout and routes The sender, usually the one most knowledgeable of the instance, gives information about how the instance is made up geographically, as this can affect tactics and eventual escape routes if a battle goes badly. In labyrinthine instance it is also good to find your way around as efficiently as possible. Example: 9 To Talk or not to Talk: Tactical Communication and Behaviour in MMORPGs P1: ”Which way is it now?” P2: ”Your quest is to the left, the rest of the instance is to the right. You go, we wait.” At this point the group has come to an intersection in the caverns of the dungeon. P1 has a quest in which he must talk to a person to the left, a quest of which P2 knows. The rest of the party then waits for P1 to talk to the person before they all continues on with the instance. • Information about events There are sometimes certain events in an instance that players need to be aware of, for example that the enemy might teleport away if it reaches a certain health level. The players need to be aware of such events and plan their actions and limited resources accordingly. Example: P1: “Wait” P1: “Adds” ”Adds” is an abbreviation of “additionals”, which means that more opponents are coming in from outside the battle. This particular message was stated during the fight with the last boss, sadly it came too late. P1 observed the adds a bit late, and the fact that everyone concentrated on the fight with the boss and did not read the message early enough, led to the death of all the characters. • Orders These are orders, usually from the party leader, and is usually only given in larger combats, and to distribute personnel resources to different areas of combat, especially when facing multiple enemies. Example: P1: “Hex on Star!” P2: “OK.” Hex is a spell that the Shaman can cast that turns an opponent into a frog, which then cannot hurt anyone. The Star is an icon that the group leader can place above an enemy to mark him out before others. There are several different looking icons that help a leader to direct the battle, and concentrate the damage on certain individuals. • Banter Small talk and jokes to relieve tension and to inform about events outside of the instance and even the game. Also conversations about items received from monsters. Example: P1: “Everybody’s got their health bar above their heads now =P” P2: “We’re all gonna die ><” P1: “I’m afraid of that ^^” P3: “P1 pays repairs” P4: “We’d best keep ahead of you then :P” P1: “Yup ^^” This was in the immediate beginning of the session. P1 (Healer) had changed the healing interface. This was a remarkably accurate prediction by P2. Note the smileys (=P, ><, and ^^) to simulate facial expressions. Some playful banter but also a comment of tactics, as the players need to keep in front of the healer so that he/she can se how much health they have left. 10 Clas Olson Fig. 2: The players encounter a Boss Results Because of the lack of interested participants there have been only three full experiments done for this project. The results published in this report is thus more focussed on a few sessions and interviews with players outside of instances, than extensive empirical studies of many gaming sessions. Roles, Training, and Professionalism There is a distinct difference in communicating in WoW once players have reached a certain level of experience in the game. As they play more and more, talk about combat with other players, and search for tactical information about how to best perform in combat, they learn that there are distinct roles in combat that are almost ubiquitous in most MMORPGs similar to WoW. These are the Healer, the Damage Dealer, and the Tank (described more thoroughly under Combat Schemas, below), and this is how most people define themselves when they do battle (as opposed to race such as Night Elf and Human, or class such as Warrior or Shaman). There are also some people who are not so specialised in a single role, but perform several roles, a so-called ”hybrid”. When a character and player is trained in this role he/she knows what to do in combat, and his/her comrades know what to expect of him/her. In other words, player develop schemas of playing[6], discussed further below. These roles, which originated in the role-playing game DUNGEONS & DRAGONS[12], started to be developed for the computer games in EVERQUEST[9], which was released in 1999. They were not explicitly named thus in the game, but were developed by the players themselves, and the tactics and roles were then spread among the gaming population through in-game means, but also outside the game through internet chats and forums. These roles then easily transferred to other later games which has a similar class structure. 11 To Talk or not to Talk: Tactical Communication and Behaviour in MMORPGs Most of these games (such as WARHAMMER ONLINE[10] and WORLD OF WARCRAFT) do not mention the classes explicitly in the game; this is something that the player have to figure out on his own. One exception that does mention the roles is LORD OF THE RINGS ONLINE[11]. What happens then, when playing with experienced players, is that they do not communicate with each other during the combat itself, instead performing the duties of their roles. An example combat situation might look like this: The party consists of five people (1 healer, 1 tank, 3 damage dealers). They see the monster they are to defeat in the distance (see Fig. 2). If this is some kind of powerful monster or boss with special abilities these might be discussed, and tactics for this particular monster is brought up. Players who have already faced this monster share their experience, but most of the players probably already have well-practised schemas [5,6] which they go through when facing enemies. The Tank then asks everyone if they are ready, and then rushes into combat before anyone else, as it is his/her role to attract all the damage the monster can deal onto him-/ herself. From this point on there is usually no communication whatsoever. Everyone performs their duties as decided by their role, and everyone expects that everyone knows what to do. The Healer can see whether the Tank’s life is low, and then heals him/her. The only time where communication is needed is when there is some new important event happening, such as more enemies rushing in to support the monster (called “adds”). The other members might be concentrating heavily on the fight with the big monster and thus not see the adds. Communication is then necessary so that the party is not surpriced by flanking manoeuvres. Experienced players know what to do in such a situation, and once more there is no communication. After a battle there might be a discussion on tactics, a debrief, when better ways to fight the monster or boss is suggested, for there is a high probability that the party might redo the instance at least once more. Below is a table describing a common procedure when experienced and professional players communicate in a battle situation: Pre-Battle Communication Actions Battle Post-Battle Discussing the tactics and methods best used to defeat the monster(s). Usually none. If important events is observed by some, this is brought to the attention of the others. Revising the tactics and methods best used to defeat the monster(s) next time. Loose banter between players to relieve the stress of battle. Looking through the abilities of your character. Performing your role (Tank, Healer, Damage Dealer). Looking through and getting the spoils and awards the monster gives the characters. Fig. 3: Common communication procedures among experienced groups When players are more unfamiliar with themselves, their own abilities, and one another, for example if they just met in the game world and decided to do an instance together, they have a much greater need to communicate with each other in a more obvious way. If they are already well-versed in the tactics of their role this will be much easier, since the roles are common not only in WoW but also in other similar games. Almost everyone who has played such an MMORPG for more than a month knows what a 12 Clas Olson Tank, a Healer, and a Damage Dealer (or DPS) does, and knows how best to co-operate with them. There might though be more discussion about how different players behave in combat, some Tanks are more careful than others who just rush into combat; some Healers prefer to concentrate on evenly distributing their healing power among several players. Every player has their different set of experiences when playing the game, and communication is important so that everyone knows what is going to happen, and how they are going to act, before the combat starts. Ducheneaut et al.[7] proposes that WoW is not very social when it comes to the actual activities you perform as a group together, that is explicit social interaction, and this might also be a reason why communication in general is so low in combat situations. The general lack of social interaction in groups may discourage a more active communication in combat, but in my experiments there were a greater prevalence of banter and casual communication when using voice compared to text, but also when using only text communication, time was spent to tell jokes and talk about events outside the instance, or even outside the game. Explicit social interaction does exist but it may not be as common as in real life, or as important to success in the game as sometimes proposed, as Ducheneaut et al. also states. Björk et al.[2] mentions implicit, or non-verbal, communication, that the fighter pilots’ (in my case the characters’) actions is in itself a form of communication. This may very well also be the case in WoW, as every member in the party studies the actions of the other players, in order to plan their own actions. Often it is the Tank that is the origin of actions, as it is he/she that is attracting the enemy’s attention, he/she then often leads the combat, and the other players observe him/her first. Combat Schemas Lindley and Sennersten discusses schemas for developing cognitive operations for game play[6], and it is obvious from observations of the experiments and from the answers of the questionnaire, that players quickly develop schemas for how to perform at their best in combat in a party. These schemas are different depending on which role you have in the party. Below are schema types for players in general (characters perform general + role schema in combat) and the different roles (Tank, Healer, and DPS) in different situations (before combat and during combat). These were developed based upon the experiments, and interviews with some of the participants. Also described are game play schema types that are used for the entire party during instances. General Behaviour Before Combat During Combat During Movement 1. Inform party of incoming enemies from outside combat. 1. Discuss abilities and tactics of the enemy. 2. If needed, remind players of their roles and the 1.1. Revise partyʼs tactics to increase tactics of the party. effectiveness. 3. Keep visual contact with other party members. Immediately before combat 1. Check personal buffs, and that you abilities are in order. Fig. 4: General behaviour before and during combat 13 To Talk or not to Talk: Tactical Communication and Behaviour in MMORPGs Tank Behaviour Before Combat During Combat During Movement 1. Stay ahead of party. 2. Observe enemy. Inform party members of enemyʼs type and position. Immediately before combat 1. Make sure all characters are ready for combat. 2. Inform party members of impending charge. 3. Charge into combat. 1. Keep close contact with enemy (when an enemy is selected, it is automatically attacked when the character is close enough). 2. Make sure enemy is attacking Tank. 2.1. If not, use abilities designed to draw the enemyʼs attention to Tank. 3. If health reaches critical levels, call for healing. Fig. 5: The Tankʼs behaviour before and during combat Healer Behaviour Before Combat During Combat During Movement 1. Stay away from potential enemies. 2. Make sure all characters have appropriate buffs. Immediately before combat 1. Take position at the back of the party. 2. Get mentally prepared for combat (rehearse tactics, establish healing priorities, and so on). 1. Monitor the health levels of party members. 1.1. If health reaches low levels, administer healing (frequency of casting healing spells must be adjusted according to the abilities of the Healer, and the priorities of the party members; Tanks are prioritised higher than DPS:s). 2. Update short-duration buffs that are soon ending. 3. Stay away from all enemies. 4. If enemies attack Healer, use abilities designed to reduce the enemyʼs aggression towards Healer. Fig. 6: The Healerʼs behaviour before and during combat DPS Behaviour Before Combat During Combat During Movement 1. If mêlée DPS, keep close contact with enemy. else 1. Make sure to be able to quickly reach the enemy, if ranged DPS, keep within range of your but let the Tank reach it first. weapons and spells, and stay out of contact with Immediately before combat the enemy. 1. If mêlée DPS, charge as soon as the Tank has 2. Concentrate on dealing as much damage to the got the attention of the enemy. enemy as possible. 3. If enemies attack DPS, use abilities designed to reduce the enemyʼs aggression towards DPS. 4. If health reaches critical levels, call for healing. Fig. 7: The DPSʼs behaviour before and during combat 14 Clas Olson Party Behaviour Before Combat During Combat During Movement 1. Maximise damage on the enemy while minimising damage to party. 1. Do not attract the attention of monsters the party 2. If additional monsters (adds) come during a boss do not intend to fight. fight, distribute resources to deal with them. Immediately before combat 2.1. If the collective danger of the adds is greater 1. Make sure as few additional monsters as than the boss, greater resources (including possible will get involved in the combat. main Tank) is distributed to adds. 2. Eliminate potential additional monsters before a 2.2. Otherwise, the main Tank remains with the boss fight. boss, and one or several DPS deal with the 3. If possible, perform Draw tactic. (This is a adds. common tactic when one character, usually either (Adds are usually weaker enemies that the Tank or a fast moving character, act as lure attack en masse, and thus often are more and approaches the enemy/-ies and draw their dangerous than the boss. But since the attention. The other characters then ambush the individuals have less health, the offensive enemies. A large group of enemies can in this power of a group can be quickly decreased, way be piece by piece reduced in number and as opposed to the boss, which will retain its finally defeated.) offensive power until killed.) Fig. 8: The Partyʼs behaviour before and during combat The Tank and the DPS always try to stay in combat as much as possible, while the Healer usually does not attack the enemy at all, instead spending all his time concentrating on the health and status of his comrades. If he would start attacking, not only would he draw more attention to himself, he would also probably neglect his healing duties, possibly to the death of the entire party. The DPS, as opposed to the Tank, always try to stay away from harm’s way much like the Healer, while still be able to attack his enemy. He can reduce the attention that he draws with his attacks by using special abilities, or by making sure the tank gets more attacks on the enemy, but the latter is usually the DPS’s role. The Tank is the only one in the party that is trying to get in harm’s way, and thus save the others in a stereotypical heroic way. In this sense he is similar to the Healer, but he prevents damage to his comrades, instead of healing damage already done. Fig. 9 describes these relations, and the roles that are connected by lines are good prospect for combinations in hybrid roles. For example, a Damage Dealer would be a good combination with a Healer, because both stay away from harms way, and a Tank might also consider doing a lot of damage at the same time as drawing the attention of the enemy. 15 To Talk or not to Talk: Tactical Communication and Behaviour in MMORPGs Fig. 9: The relation between the different roles There are many different classes in WoW, and many of these can be utilised in many of the roles mentioned above. But no matter what class a character is in, it will usually confer to these schemas, as it is these that are expected in the WoW community. The druid class, for example, is a class that can perform well in all roles, depending on the skill set that the player has chosen for his/her character. Even if he is ”specced” (that is, ”specialised”) for a certain role, he could perform the other two roles if the effort is not that large. But for challenging instances it is recommended that every party member perform his/her role exclusively, in order not to lose that role’s resources. This is especially true in 5-man instances, while in 40-man raids this rule is more loose, for there usually are someone who can step into another one’s role. These schemas are learned from experience with playing in a party, and from the instructions of other more experienced players. The latter is something that is seldom seen in a single-player game, and only then if you make contact with people which play the same game, and are willing to share their knowledge. In an MMORPG like WoW all party members have a need for everyone to perform at their best, so they will often inform less experienced players of how to best play their role in the party. The purposes of text versus voice communication I have compared the uses of voice communication and text communication during combat situations in WoW, and in general voice was considered the preferred medium to communicate. Using text requires that the players use both their hands for typing, and this essentially freezes them in combat and they lose precious time. It also takes the attention from the combat itself if the player cannot write on a keyboard and at the same time look on something else on the screen (see Fig. 10). 16 Clas Olson Fig. 10: Divided attention The receiver of the text message (in this case the whole party) must also divert their attention toward the text chat window now and then to see if there are some new messages and this also means a distraction from the battle itself. It may also take a long time before the player actually looks in the text chat window, up to a minute (the average length of a boss fight), and thus miss the urgency of such a message. When using voice the player can still concentrate his/her visual attention on the battle, while still receiving the information via his/her ears, and it will be received at the same time as it is sent. The voice communication usually fits better in with combat situations, where information must be transmitted quickly and effectively, and all the intended receivers must hear it immediately. Text communication on the other hand is by many considered to be a “calmer” medium, where you can communicate at your leisure in an unhurried way. It can also, since it is integrated into the game, be used to communicate with other players who are not on the Ventrilo server, enabling easy commerce and communication between the hundreds of players in an area covered by the text chat. Information about items and quests (so called linking) can also be performed, when a person drags something to the chat bar, and everyone receiving can read about the item, character or quest. To read and describe such a thing would be tedious and only be shared with your fellows in the Ventrilo server. There is also a difference in language when people are speaking instead of writing. Because of the awkwardness of writing text messages are by necessity kept short and to the point, and it helps of course if the party members are aware of the meaning of terms such as “adds”, “hex”, “buff”, and so on, but that vocabulary is easily learned in a couple of weeks of play. The utility of these short words in text is obvious, but they are also used in spoken work, while using Ventilo for voice communication. Most likely this is due to the 17 To Talk or not to Talk: Tactical Communication and Behaviour in MMORPGs utilitarian nature of the words, but voice communication has an advantage in that it is easy to add more information and clarification. There is also clearly more “loose” communication and banter between the players when using voice instead of text, that is, more talk which is not related to combat or even to the game at all. This further emphasises the ease of communication via voice instead of text. Why does not everyone use voice? Voice communication may be the most efficient tool for communicating with party members in combat, short of actually being in physical proximity and earshot of each other, but most people still do not use it often while they play together. There may be many reasons for this, some more social ones are brought up by Clive Thompson[8], who argue that when using voice, the veil of anonymity is lifted, and many preconceptions about age, gender, nationality, and even race hinders people from revealing something as personal as their voice. A major fact would probably be that, while the voice communication software is free, the physical equipment usually is not. There are a few computers (commonly laptops and Macintoshes) that have internal microphones, but these are usually of low quality and located far from the mouth of the player. The best sound quality would then come from a headset, or a separate microphone and earphones. This also has the advantage that the microphone can easily be exchanged if it is broken, which one can not do with the internal microphones. Commonly, casual computer players do not have headsets, or might not even know of voice communication software at all. It is also not very convenient and easy to start up a conversation using voice. Since you have to use third party software, a separate program must be run, which have to be the same program and version that the other players use, and the group must have access to a server which provides the communication hub. The address and maybe also the password to this server must then be passed around to all the members of the party so they can log in. Players who play with each other often, such as members of the same guild, have an easier time doing this, since they can plan ahead and prepare themselves, but people who have just met in the world and want to play an instance have more trouble with this. If the voice communication software were included in the software of the game, this could be redeemed, and while people may not have microphones, they would be encouraged to acquire one if WoW tells you that it is easy to use and talk to others in the game, using no other software but WoW itself. The importance of communicating in combat The hypothesis that I established in the experimental design was this: “ A group of people will perform better in co-operative combat in MMORPGs if they communicate via voice instead of text.” As stated above, experienced players rarely communicate during battle, and only a little before or after a battle. But the communication they perform is often of vital importance, especially if someone in the group has not faced this particular challenge before. And mistakes are always made by everyone, so communication is necessary to effectively perform in combat situations in an MMORPG. It is also apparent from the experiments that voice communication is much more efficient than text communication, since the latter often involves a distraction both to send and receive, and is usually brought to the attention of the receiving player much later than if the same message had been transmitted via voice. Though there was a very small difference in game time for the two sessions of an experienced group, the fact that the group failed to defeat the last boss of the instance, and this was due to slow communication as shown in the later questionnaires, proves the point that voice communication is better in combat than text communication. 18 Clas Olson I would thus say that game developers should be more aware that voice communication is so important in battle, that they should include such software in their games in order to encourage better performance in one of the most important parts of most such games, combat. A simpler thing to do, as a start, would be to implement the possibility of having an auditory signal to sound upon receiving a text message, so that the players can direct their attention towards the text chat window only when needed. Conclusion Despite the experimental sample being smaller than hoped for, much interesting data have been gathered during the analysis. Surprisingly, one a player have reached a certain development of his/her skills and learned the schemas of his/her role in combat, quite little communication is needed in combat. One only continues the battle in the same routine as always, and only when something unexpected happens and something changes, is communication needed. But it is clear that during those events, clear and fast communication is crucial, and there vocal communication has an advantage over text, as shown by the death of one of the experimental parties in a text session. Future Studies Communication being a very important part of co-operative game play, there is a great potential for further studies. Apart, of course, from extending this study with more of the same; more participants in the experiments and more statistically solid data. For example, linguistic studies of the difference of language in combat and in more calm situations, or the difference between text language and voice language, and the development of new terms and expressions in the virtual gaming world. One could extend this study a bit more by not allowing any communication whatsoever, and see how different groups, experienced and inexperienced, perform in stressful combat. There could be studies in different MMORPGs (or even other completely different multiplayer games), and these could be used to determine the difference of communication between the different types and genres of games. 19 To Talk or not to Talk: Tactical Communication and Behaviour in MMORPGs References [1] Anolli, Luigi, Ciceri, Rita, and Riva, Giuseppe; SAY NOT TO SAY : NEW PERSPECTIVES ON MISCOMMUNICATION; 2002 (IOS Press; Amsterdam, Netherlands) [2] Björk, Jenny, Furberg, Bibbi, Granåsen Magdalena, Johansson Katarina, Lange, Andreas, Wallqvist, Elin, Berggren, Peter, and Nählinder, Staffan; COMMUNICATION IN EXPERT TEAMS: PILOT - A METHOD OF ANALYSIS; 2003 (Swedish Defence Research Agency; Lindköping, Sweden) [3] World of Warcraft Europe Website - http://www.wow-europe.com/ [4] Ventrilo Website - http://ventrilo.com/ [5] Mandler, Jean Matter; STORIES, SCRIPTS, AND SCENES: ASPECTS OF SCHEMA THEORY; 1984 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Hillsdale, New Jersey, USA) [6] Lindley, Craig and Sennerström, Charlotte; GAME PLAY SCHEMAS: FROM PLAYER ANALYSIS TO ADAPTIVE GAME MECHANICS; 2007 (Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlshamn, Sweden) [7] Duchenaut, Nicolas, Yee, Nicholas, Nickell, Eric, and Moore, Robert J.; ”ALONE TOGETHER?”: EXPLORING THE SOCIAL DYNAMICS OF MASSIVELY MULTIPLAYER ONLINE GAMES; 2006 (Palo Alto Research Center; Palo Alto, California, USA) [8] Thompson, Clive; VOICE CHAT CAN REALLY KILL THE MOOD ON WOW; 2007 (Wired Web Magazine, http://www.wired.com/gaming/virtualworlds/commentary/games/2007/06/ games_frontiers_0617) [9] Everquest on Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Everquest [10] Warhammer Online Website, http://www.warhammeronline.com/ [11] Lord of the Rings Online Website, http://lotro.turbine.com/ [12] Dungeons & Dragons Website, http://www.wizards.com/default.asp?x=dnd/ welcome&amp;dcmp=ILC-DND062006FP [13] Wiklund, Mats; GAME MEDIATED COMMUNICATION: MULTIPLAYER GAMES AS THE MEDIUM FOR COMPUTER BASED COMMUNICATION; 2005 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) [14] Glas, René; PLAYING ANOTHER GAME: TWINKING IN WORLD OF WARCRAFT; 2007 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) [15] Koivisto, Elina M. I.; SUPPORTING COMMUNITIES IN MASSIVELY MULTIPLAYER ONLINE ROLE-PLAYING GAMES BY GAME DESIGN; 2003 (Digital Games Research Association, http:// www.digra.org) [16] Koivisto, Elina M. I. and Wenninger, Christian; ENHANCING PLAYER EXPERIENCE IN MMORPGS WITH MOBILE FEATURES; 2005 (Digital Games Research Association, http:// www.digra.org) [17] Montola, Markus; DESIGNING GOALS FOR ONLINE ROLE-PLAYERS; 2005 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) 20 Clas Olson [18] Eladhari, Mirjam and Lindley, Craig A.; PLAYER CHARACTER DESIGN FACILITATING EMOTIONAL DEPTH IN MMORPGS; 2003 (Digital Games Research Association, http:// www.digra.org) [19] Kujanpää, Tomi, Manninen, Toni, and Vallius, Laura; WHAT’S MY GAME CHARACTER WORTH – THE VALUE COMPONENTS OF MMOG CHARACTERS; 2007 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) [20] Lin, Holin and Sun, Chuen-Tsai; CASH TRADE WITHIN THE MAGIC CIRCLE: FREE-TOPLAY GAME CHALLENGES AND MASSIVELY MULTIPLAYER ONLINE GAME PLAYER RESPONSES; 2007 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) [21] Alves, Tiago Reis and Roque, Licínio; BECAUSE PLAYERS PAY: THE BUSINESS MODEL INFLUENCE ON MMOG DESIGN; 2007 (Digital Games Research Association, http:// www.digra.org) [22] Lee, Yu-Hao and Lin, Holin; AN IRRATIONAL BLACK MARKET? BOUNDARY WORK PERSPECTIVE ON THE STIGMA OF IN-GAME ASSET TRANSACTIONS; 2005 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) [23] Boman, Magnus and Johansson, Stefan J.; MODELING EPIDEMIC SPREAD IN SYNTHETIC POPULATIONS — VIRTUAL PLAGUES IN MASSIVELY MULTIPLAYER ONLINE GAMES; 2007 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) [24] Lin, Holin and Sun, Chuen-Tsai; THE ‘WHITE-EYED’ PLAYER CULTURE: GRIEF PLAY AND CONSTRUCTION OF DEVIANCE IN MMORPGS; 2005 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) [25] Galarneau, Lisa; SPONTANEOUS COMMUNITIES OF LEARNING: LEARNING ECOSYSTEMS IN MASSIVELY MULTIPLAYER ONLINE GAMING ENVIRONMENTS; 2005 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) [26] Myers, David; SELF AND SELFISHNESS IN ONLINE SOCIAL PLAY; 2007 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) [27] Whang, Leo Sang-Min and Kim, Jee Yeon; THE COMPARISON OF ONLINE GAME EXPERIENCES BY PLAYERS IN GAMES OF LINEAGE & EVERQUEST: ROLE PLAY VS. CONSUMPTION; 2005 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) [28] Seay, A. Fleming, Jerome, William J., Lee, Kevin Sang, and Kraut, Robert; PROJECT MASSIVE 1.0: ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT, SOCIABILITY AND EXTRAVERSION IN MASSIVELY MULTIPLAYER ONLINE GAMES; 2003 (Digital Games Research Association, http:// www.digra.org) [29] Taylor, T. L.; POWER GAMERS JUST WANT TO HAVE FUN?: INSTRUMENTAL PLAY IN A MMOG; 2003 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) [30] Adams, Suellen; INFORMATION BEHAVIOR AND THE FORMATION AND MAINTENANCE OF PEER CULTURES IN MASSIVE MULTIPLAYER ONLINE ROLE- PLAYING GAMES: A CASE STUDY OF CITY OF HEROES; 2005 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) [31] Salazar, Javier; ON THE ONTOLOGY OF MMORPG BEINGS: A THEORETICAL MODEL FOR RESEARCH; 2005 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) [32] Payne, Matthew; ONLINE GAMING AS A VIRTUAL FORUM; 2005 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) 21 To Talk or not to Talk: Tactical Communication and Behaviour in MMORPGs [33] Yee, Nick; MOTIVATIONS OF PLAY IN MMORPGS; 2005 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) [34] Lee, Ichia, Yu, Chen-Yi, and Lin, Holin; LEAVING A NEVER-ENDING GAME: QUITTING MMORPGS AND ONLINE GAMING ADDICTION; 2007 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) [35] Pargman, Daniel and Ericsson, Andreas; Law, Order And Conflicts Of Interest In Massively Multiplayer Online Games; 2005 (Digital Games Research Association, http:// www.digra.org) [36] Kücklich, Julian; MMOGS AND THE FUTURE OF LITERATURE; 2007 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) [37] Lin, Holin, Sun, Chuen-Tsai, and Tinn, Hong-Hong; EXPLORING CLAN CULTURE: SOCIAL ENCLAVES AND CO-OPERATION IN ONLINE GAMING; 2005 (Digital Games Research Association, http://www.digra.org) 22 Clas Olson Appendix A: Experiment Design Introduction This experiment will demonstrate the need for vocal communication in combat situations in most Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games. It is part of a 10-week project in the Master Programme in Game Design. I will record the communication between the group members while they are playing a session of WORLD OF WARCRAFT and will be listening to them at the same time. They will the answer questions about their experience with and without vocal communication, and describe their opinions about the differences. Hypothesis A group of people will perform better in co-operative combat in MMORPGs (Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games) if they communicate via voice instead of text. The Game As a massively multiplayer online game, WORLD OF WARCRAFT enables thousands of players to come together online and battle against the world and each other. Players from across the globe can leave the real world behind and undertake grand quests and heroic exploits in a land of fantastic adventure. WORLD OF WARCRAFT (commonly acronymed as WOW) is a massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG). It is Blizzard Entertainment's fourth released game set in the fantasy Warcraft universe, which was first introduced by WARCRAFT: ORCS & HUMANS in 1994. WORLD OF WARCRAFT takes place within the world of Azeroth, four years after the events at the conclusion of Blizzard's previous release, WARCRAFT III: THE FROZEN THRONE. Blizzard Entertainment announced WORLD OF WARCRAFT on September 2, 2001. The game was released on November 23, 2004, celebrating the 10th anniversary of the Warcraft franchise. The first expansion set of the game, THE BURNING CRUSADE, was released on January 16, 2007. On August 3, 2007, during the 2007 BlizzCon event, Blizzard announced a second expansion set, WRATH OF THE LICH KING, which was released on November 13, 2008. With more than 11 million monthly subscribers, WORLD OF WARCRAFT is currently the world's largest MMORPG in those terms, and holds the Guinness World Record for the most popular MMORPG. In April 2008, WORLD OF WARCRAFT was estimated to hold 62% of the massively multiplayer online game (MMOG) market. Goals and Basic Game Play The goal of the game is based upon each player’s preferences. If the player is interested in player versus player combat, or PvP for short, he or she may focus on this part of the game. But if the player is more interested in cooperation and to overcome the challenges the game designers have created, also known as player versus environment or PvE, he or she may instead spend more time in different dungeons and specific group-challenges where five or more players have to communicate and cooperate to overcome each challenge they face together. There are three archetypes of characters in WORLD OF WARCRAFT; the Tank is the damage-taker and will ideally be the one targeted and damaged by enemy AI. The Damage Dealer is as it states a character that does damage to enemies while the Tank keeps the enemy’s or enemies’ attention. Lastly is the Healer who, as stated earlier, can give the Tank health back at the expense of mana. There are many other features in World of Warcraft, but it is only player versus player combat and player versus environment combat that is of main interest since the game is a Role playing game where players have to battle and kill enemies to gain experience and to 23 To Talk or not to Talk: Tactical Communication and Behaviour in MMORPGs level-up. Many people are interested in role playing as well, but in the end they usually have to fight monsters to level up and gain a higher status among the other role players. Apparatus Every player is assumed to have at least the minimum requirements for his or her computer. The minimum and recommended requirements for PC and Macintosh are as follows: Minimum requirements: • Windows XP (Service Pack 3), Windows Vista (Service Pack 1) • Intel Pentium 4 1.3 GHz or AMD Athlon XP 1500+ • 512 MB RAM (1GB for Vista users) • 3D graphics processor with Hardware Transform and Lighting with 32 MB VRAM such as an ATI Radeon 7200 or NVIDIA GeForce 2 class card or better • DirectX-compatible sound card or motherboard sound capability • 15 GB free hard drive space • A keyboard and mouse are required. Input devices other than a mouse and keyboard are not supported. • You must have an active broadband Internet connection to play • • • • Mac OS X 10.4.11 or newer PowerPC G5 1.6 GHz or Intel Core Duo processor 1 GB RAM 3D graphics processor with Hardware Transform and Lighting with 64 MB VRAM such as an ATI Radeon 9600 or NVIDIA GeForce Ti 4600 class card or better • 15 GB free hard drive space • A keyboard and mouse are required. Input devices other than a mouse and keyboard are not supported. • You must have an active broadband Internet connection to play. Recommended Specifications: • Windows XP (Service Pack 3), Windows Vista (Service Pack 1) • Dual-core processor, such as the Intel Pentium D or AMD Athlon 64 X2 • 1 GB RAM (2 GB for Vista users) • 3D graphics processor with Vertex and Pixel Shader capability with 128 MB VRAM such as an ATI Radeon X1600 or NVIDIA GeForce 7600 GT class card or better • DirectX-compatible sound card or motherboard sound capability • Broadband Internet connection. • Multi-button mouse with scroll wheel recommended. • • • • Mac OS X 10.4.11 or newer Intel 1.8GHz processor or better 2 GB RAM 3D graphics processor with Vertex and Pixel Shader capability with 128 MB VRAM such as an ATI Radeon X1600 or NVIDIA 7600 class card or better • Multi-button mouse with scroll wheel recommended. Stimuli The play sessions will be played out in an instance in the game. An instance is a dungeon where a group of up to five players can join together to fight a series of battles and journey through an environment, until they reach the end boss, and the final fight ensues. The instance is a private area; the moment the group enters the instance, which is represented 24 Clas Olson as a portal in the public world, they are transported the their own, private, version of the instance. No other players can get into their instance unless they join the group, and they thus have the whole dungeon for themselves. Participants For each pair of sessions, I will use a group of four or five participants. None of these need be physically present, as they will record their sessions themselves for convenience. They will also answer the questions on an online survey. Procedures In the beginning of the experiment the test subjects will be asked to fill in the pre-test questionnaire, which is located online. Then they will play through the instance one time, and after that is finished, they will answer the questions for the first session. Then they play through the same instance again, under different conditions of communication, and after that they answer the questions for the second session. Method For all the experiments, I will vary the conditions as much as possible. For each session there are three alternatives; communicating using only voice, only text, or no communication at all, which is used as a control test. These alternatives, and the order in which they come, will be changed for each experiment. During the voice sessions, all participants will have the possibility to communicate by voice, using headsets or microphones and headphones. The software we will use will be Ventrilo, a common voice chat program similar to Teamspeak. I will listen in on the communication between the players, and will also be recording the communications. The session will last until the group complete the instance. Then there will be a pause for answering questions. After that, the second session will begin. Now the same instance is played, but this time under different circumstances. The participants will be asked the questions described in Appendix A1: Questions for the Participants after each session of play. Expected Result I expect that it will take a shorter time to play through the instance, and thus the players will perform better in battle, while using voice to communicate with each other. I also expect that the participants will be more comfortable, and find it more helpful, to use voice instead of text to communicate. They will probably forego using the keyboard to type in the middle of combat in favour of concentrating on the battle, thus losing the ability to communicate. 25 To Talk or not to Talk: Tactical Communication and Behaviour in MMORPGs Sub-appendix A1: Questions for the Participants Before starting the first play session: 1. Name:______________________________________________________ 2. Age:_________ 3. Gender: Male 4. For how long have you been playing computer games? Less than 3 years More than 10 years 5. Female 3-5 years For how long a time have you been playing World of Warcraft? Less than 3 months 3-6 months 12-24 months More than 24 months 6. 5-10 years 6-12 months How long have you used voice chat software (Ventrilo, Teamspeak, Skype, etc.) in games? Never used More than 3 years Less than 1 year 26 1-3 years Clas Olson After the first play session: 1. Have you used text/voice to communicate during combat in World of Warcraft any time previously? Yes No 2. Did you communicate with your team-mates using text/voice during this session? Yes No 3. If yes, did you chat/talk during all encounters with the bosses? Yes No, only these:___________________________________ 4. Did you find it helpful to chat with/talk to your team-mates during combat? (0 = Not helpful, 4 = necessary) 0 1 2 3 4 Further comments: __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ 5. Was chatting/talking necessary for you to perform your role (healer, tank, DPS, as opposed to overall combat performance) effectively in combat? Yes Not necessary, but helpful No, I did not need it Further comments: __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ 6. Did you lose, or perform badly in, a battle because of lack of communication? Yes No Further comments: __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ 7. Other comments: __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ 27 To Talk or not to Talk: Tactical Communication and Behaviour in MMORPGs After the second play session: 1. Have you used text chat/voice to communicate during combat in World of Warcraft any time previously? Yes No 2. Did you communicate with your team-mates using text chat/voice during this session? Yes No 3. If yes, did you chat during all encounters with the bosses? Yes No, only these:___________________________________ 4. Did you find it helpful in combat to chat with/talk to your team-mates? Yes No Further comments: __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ 5. Was chatting/talking necessary for you to perform your role (healer, tank, DPS, as opposed to overall combat performance) effectively in combat? Yes Not necessary, but helpful No, I did not need it Further comments: __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ 6. Did you lose, or perform badly in, a battle because of lack of communication? Yes No Further comments: __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ 7. Which method of communication (voice or text chat) do you find most helpful in combat? Voice Text chat Further comments: __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ 8. Other comments: __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ 28 Clas Olson Appendix B: Transcriptions Here is transcribed examples of important comments and conversations that the players made during the gaming sessions in the experiments. All players will only be referenced by a number (P1, P2, P3, …). It may not be the same player referenced by the same number in different conversations. Voice Communication Session P1: “Well, we just go as usual, then?” This simple statement by the group leader is enough so that everyone will know what to do, no new procedures or tactics is to be implemented during the instance. It was stated in the immediate start if the instance. P1: “How about these dragons, are there any difference between them?” P2: “Yeah, later they will get some special abilities, but this one is a Tank, that one is a DPS, and that one over there is a Healer.” A more experienced player explains the abilities of some dragons that the players will ride upon and use throughout the instance. P1: “I am new to this, I have aggro down here.” “Aggro” means that the player has attracted the aggressive attention of some monsters, usually something the Tank in a group intends to do, while the others try to stay out of harm’s way and hurt the monsters as much as possible. The fact that this player (which is a Damage Dealer) was new to the instance was the reason that he died while trying to get away from the monsters he had attracted. P1: “Hex on Star!” P2: “OK.” Hex is a spell that the Shaman can cast that turns an opponent into a frog, which then cannot hurt anyone. The Star is an icon that the group leader can place above an enemy to mark him out before others. There are several different looking icons that help a leader to direct the battle, and concentrate the damage on certain individuals. P1: “Does anyone remember what this guy did?” P2: “Yeah, he started to fire lightning over a large area, and then there was some sort of laser beam thing that followed us and that we should stay away from.” P1: “OK, let’s go then.” This was before one of the bosses, where they discuss the abilities of the boss, and how to counter them. P1 is the Tank in this case, and it is always the Tank that takes the initiative and running into battle, forewarning his/her comrades that he/she is about to do so. P1: “We can try and stand behind him and see if we still are affected.” This was later in the same battle as above, one of the few conversations during a battle. It was a test to see if the boss’s shower of lightning bolts extended around his back. P1: “Let’s stand back here so I can explain to XXX how this guy works. He casts some spell that freezes the ground clockwise around the ring, so we have to kite around to stay away from it. Then he teleports to the middle and casts some kind of big Arcane Explosion just like in Sethekk Halls. We have to stand behind these pillars because it’s line of sight.” P2: “He only casts the freezing thing on me, so I can stand still and you can remain where you are.” 29 To Talk or not to Talk: Tactical Communication and Behaviour in MMORPGs P1: “Oh, so that’s how it works.” P2: “OK, so everyone ready? I go.” This is a more detailed discussion about tactics around a more complex boss than the ones before. P1 explains what the boss does and what they should do to counter it, but P2 (the Tank) comes in and corrects P1 about a misunderstood ability. Once again, the Tank makes sure that everyone is ready to fight before rushing in. Text Communication Session P1: “Everybody’s got their health bar above their heads now =P” P2: “We’re all gonna die ><” P1: “I’m afraid of that ^^” P3: “P1 pays repairs” P4: “We’d best keep ahead of you then :P” P1: “Yup ^^” This was in the immediate beginning of the session. P1 (Healer) had changed the healing interface. A remarkably accurate prediction by P2. Note the smileys (=P, ><, and ^^) to simulate facial expressions. Some playful banter but also a comment of tactics, as the players need to keep in front of the healer so that he/she can se how much health they have left. P1: “Snowflake on me” A Snowflake is a kind of monster, and it attacked P1 (Healer). In order to everyone to be aware that someone is attacking the Healer, which is relatively defenceless, they have too look down in the text chat window now and then, and stop concentrating on the battle for a short while, if they does not see it in the world themselves. The delay between when the message is sent and received can be long enough so that the healer can be disabled and stopped from doing his/her job, and thus the Tank will lose health quickly. P1: “Just try to keep together now” P2: “Just run away from the beam” The Healer did most of the conversation during this session, and here he/she advises the others to keep together, so that he/she can see their health bars easier. P2 reminds everyone to run away from the beam that the boss creates that follows the players around. P1: “Wait” P1: “Adds” ”Adds” is an abbreviation of “additionals”, which means that more opponents are coming in from outside the battle. This particular message was stated during the fight with the last boss, sadly it came too late. P1 observed the adds a bit late, and the fact that everyone concentrated on the fight with the boss and did not read the message early enough, led to the death of all the characters. P1: “All right, better clean out all the adds beforehand.” Revised tactics before fighting the final boss the second time. 30 Clas Olson Appendix C: Timelines 31 To Talk or not to Talk: Tactical Communication and Behaviour in MMORPGs 32