arthur andersen and the temple of doom

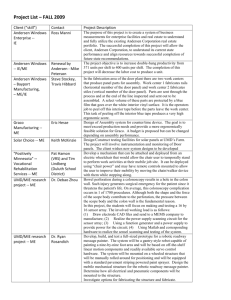

advertisement