Qualitative Study Examining the Effects of Polygyny - UW

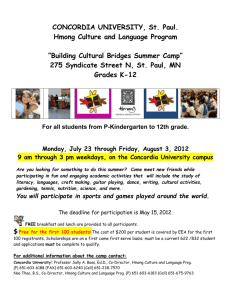

advertisement