yale senior thesis

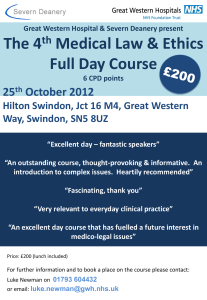

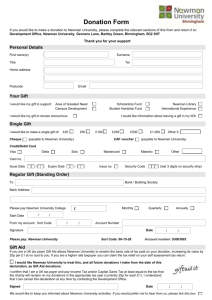

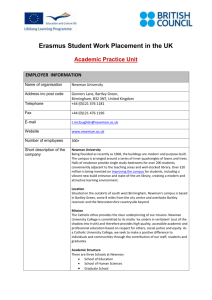

advertisement