the cognitive-style inventory

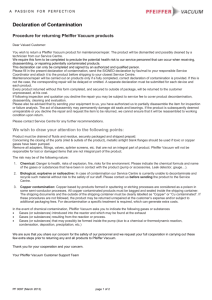

advertisement