Starbucks a Strategic Analysis

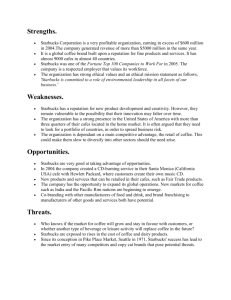

advertisement