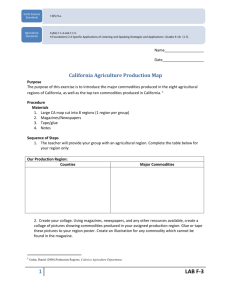

Open Research Online One thing leads to another commodities

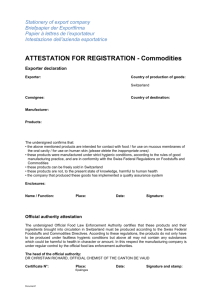

advertisement