Final Report: NJSBA School Security Task Force

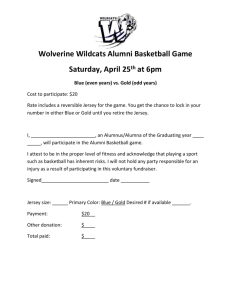

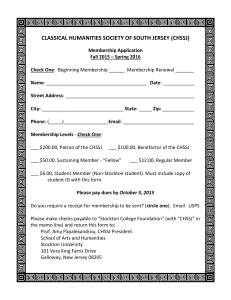

advertisement