A Pioneering Experiment in Assessing Advertising Effectiveness

advertisement

A Pioneering Experiment

in Assessing

Advertising Effectiveness

THOMAS E. COFFIN

According to this article,

there are only two basic

dimensions to the effectiveness of advertising: (I) size

of audience, and (2) depth

of impact.

The advertising industry

has been spending most of

its research dollars in measuring the audience component, with the result that

we can now measure this

dimension reasonably well.

Dr. Coffin believes it is now

time to spend more dollars

in assessing the dimension

of impact—for it is this

area which, for the future,

promises the greatest improvement in advertising

evaluation and sound media

comparisons.

there are only two basics. There are many variINantsadvertising,

of each, and many levels at which each can be described

and measured. But fundamentally these all reduce to two issues:

1. "How many peoj>le you reach"—audience size.

2. "How hard you hit them"—depth of impact.

These two basics apply whether the advertising in question

is a single advertisement, a campaign of advertisements, or a

medium of advertising.

True, there are many refinements and elaborations upon each.

Various qualifiers may be appended to the "how many" question.

For example, it may be decided that certain kinds of people are

more valuable to veach than others—this is "quality" of audience.

But this refinement is easily dealt with by differential weighting

in the audience counts. Heavy product users, for instance, can he

given more weight than light users or nonusers.

And the "how many" can be measured at various levels: circulation, readership, viewership, exposures, noting, sponsor identification, for example. Moreover, the measurement can he elahorated to include the frequency, the duplication, the cumulation,

the gross reach, and the net reach. But all such measures are

still asking basically, "How many?"

Obviously audience is the first dimension of advertising, and

much time and effort has been spent in improving the various

measures of it. But audience figures should be the starting point,

not the stopping point, in advertising measurement. Time and

effort now should he devoted to measurement of the second dimension, the depth-of-impact factor. Until both factors are included,

the advertising industry will continue to be without a proper

measure of the effectiveness of its product.

This is important for all advertising. Growing advertising

budgets are leading top management to press with increasing

urgency the question of advertising's effectiveness. And with the

advent of computers in the media-selection process, the practical

need is becoming more acute for input data on the impact as well

as the audience of media.

The industry tries to answer management's question by pointing

to how many the advertising has reached, of what quality, and with

what frequency. Likewise, this is the principal type of data thus

far at hand to feed into the computer. But in each instance

audience is only half the answer.

Three Historical Stages

Most people in the advertising business have been curiously

reluctant to "face up" to the second half of the question. This

has been evident both on the primary issue of measuring adver-

Journal of Marketing, July, 1963

tising effectiveness per se, and on the subordinate

question of measuring the comparative effectiveness

of different media. Looking back, the industry has

gone through three interesting stages;

Phase 1. For many years, tke accepted view was

to deny that it is possible to measure advertising effectiveness. Concerning advertising, per

se, the cliche was, "There are too many variables." Concerning the comparison of media,

"You can't compare apples and oranges; they

differ too much." But pressure from management continued, eventually leading to Phase 2.

Phase 2. Hesitant agreement that further measurement is needed. But with continued reluctance to address the "effectiveness" issue directly, the measurement became diverted into

amplifications of qualitative attributes: preoccupation with kinds of audiences, numbers of

exposures, reading days, page openings, frequency breakdowns, quintile analyses. This

was the diversionary phase, pursuing attractive

bypaths while avoiding the main issue.

Phase 3. The period of acquiescence. With pres-

sure from top management more intense and

with increasing concern over the "profit

squeeze"—plus the arrival of the computers,

generating additional pressures with their

appetite for explicit figures—industry opinion

is at last swinging toward an affirmative interest in the measurement of advertising effectiveness. Four recent publications have clearly

pointed up this trend.*

A Point of Perspective

Under this changing climate of opinion it may

be wise to inject a cautionary note oi historical

perspective. It has taken audience researchers

some three decades and upwards of a hundred

million dollars spent on audience research of all

varieties to arrive at the point where they can

produce reasonably accurate answers to the question of "how many." It would seem likely that it

may take nearly as long, and as many dollars, to

make comparable progress on the more difficult

question of "how hard."

With this frame of reference, it is evident that

the following case-history is not regarded as representing perfected techniques or ultimate

Toward Better Media Comparisons, A Report of the

Audience Concepts Committee of the Advertising

Research Foundation {New York: Advertising Research Foundation, Inc., 1961). Russell H. Colley,

Defining Advertising Goals for Measured Advertising Results (New York: Association of National

Advertisers, Inc., 1961). Harry Deane Wolfe, James

K. Brown, and G. Clark Thompson, Measuring Advertising Results (New York: National Industrial

Conference Board, 1962), Darrell Blaine Lucas and

Steuart Henderson Britt, Measuring Advertising

Effectiveness (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1963).

answers. Growing out of a long-standing interest

in the assessment of advertising effectiveness and

successive attempts at improving the methods

employed,^ this study represents an experimental

investigation which a few years ago undertook to

extend our efforts into the as yet untried area of

inter-media effectiveness comparisons.

The methodology outlined may prove of interest

and provide some stimulation for further exploration, while revealing some of the problems encountered in assessing advertising impact and

some attempts which have been made to deal with

them.

An Experimental Study

This experiment was a 2-wave panel study, in

which the same individuals were reinterviewed at

two points in time three months apart. The sample

was a prelisted probability sample, representing a

typical medium-sized midwestern market; 91%

of the original respondents were recovered on

Wave II.

The respondents were male and female household heads, with a final sample size of 2,441. The

study covered 22 brands advertised both on network TV programs and in weekly Magazine A,

representing 11 different product categories:

Beer

Canned soup

Cigarettes

Gasoline

Headache remedies

Deodorants

Home permanents

Packaged cheese

Packaged desserts

Razor blades

Toothpaste

Thomas E. Coffin, Tke Hofstra Study: A Measure

of the Sales Effectiveness of TV Advertising (New

York: National Broadcasting Company, Inc., 1950).

TV Today: Its Impact on People and Products (New

York; National Broadeasting: Company, Inc., 1951).

Why Sales Come In Curves (New York: National

Broadcasting Company, Inc., 1954). Strangers Into

Customers: Tke Fort Wayne Study (New York:

National Broadcasting Company, Inc., 1955).

• ABOUT THE AUTHOR. Thomas E.

Coffin is Director of Research of the

National Broadcasting Company, Inc.

The concepts in the present article have

been developed in the course of analyzing a series of major studies into the

effectiveness of television advertising,

conducted by NBC over the past several

yea rs.

Prior lo joinrng NBC tn 1949, Dr.

Coffin was Professor of Psychology and

Chairman of the Psychology Department at Hofstra College. He

received his M.A. and Ph.D. in Psychology from Princeton

Vnlvers'dy.

Jack 8. Landis, formerly Manager of Research Projects at

NBC and now Executive Director of Marketing Evaluations,

has contributed greatly to the development of the ideas and

technicfues described in this article.

A Pioneering Experiment in Assessing Advertising Effectiveness

For each of these categories the respondent was

questioned as to what brands he or she had "personally bought in the last four weeks." The "buying figures" to follow, therefore, represent the

percentage of the total sample (or specified subgroup) who claimed to have bought the advertised

brand in the last four weeks.

In the TV viewing question, a list of programs

was shown and the respondent was questioned

ahout his personal viewing of each in the last

four weeks. In the case of weekly magazines, a

list was also used, with the questioning directed

toward the last four issues. "Readers" or "viewers" here are those who claimed to have read one

or more of the last four weekly issues or watched

one or more of the last four broadcasts. Thus, in

the following sections the unit of exposure is the

advertising vehicle, rather than the commercial or

advertisement.

To maintain comparability, the same questionnaire wordings and sequences were employed on

both waves of the study. To minimize any possibility of the buying responses being infiuenced by

the media questions, these topics were separated

as widely as possible, so as to obtain the information about buying before asking about media exposure, with a number of other questions intervening.

Moreover, several additional products, programs, and magazines were included in the lists,

in order to divert attention further from the

questions of special interest and to lessen the

chance of producing a spurious relationship

between a particular product and a program or

magazine. Careful analysis of previous studies

has shown that such precautions have been effective in minimizing the possibility of inadvertent

"reversal" of cause and effect or of "conditioning"

the responses on Wave II by prior questioning on

Wave I.-^

Results

All of the figures to be reported represent the

unweighted averages of the 22 brands studied. Inspection of the individual brands indicates that

these averages properly reflected the experience

of the majority of the individual brands; about

75% of the individual brands showed the same

patterns as those pictured by the averages, while

25% of the brands deviated from the average

pattern in one way or another.

As shown in Table 1, the first overall finding

of the study was that, on a total sample basis,

there was remarkably little difference between

the buying levels for Wave I and Wave II. The

3 Why Sales Come In Curves (New York: National

Broadcasting Co., Inc., 1954), pp. 51-52. Strangers

Into Customers: The Fort Wayne Study (New

York: National Broadeasting Co., Inc., 1955), p. A-7.

TABLE 1

SOME RELATIONSHIPS OP BUYING

TO OVERALL ADVERTISING EXPOSURE

1. Overall results of survey

Total sample. Wave I

Total sample. Wave II

% buying in

past 4 weeks

19.4

19.6

2. Relationship of buying to advertising exposure

% buying,

Wave II

Exposed to advertising (TV and/or

magazine)

20.5

Not exposed to advertising

16.9

3. Relationship of buying to degree of exposure

% buying,

Wave II

Not exposed to advertising (TV and/or

magazine)

16.9

1 unit of exposure (TV and/or

magazine)

18.9

2 units of exposure. <TV and/or

magazine)

20.1

3 units of exposure (TV and/or

magazine)

21.8

4 units of exposure (TV and/or

magazine)

24.0

percentage buying the "average brand" in the

last four weeks was 19.4 for Wave I and 19.6 for

Wave II, three months later. It might seem that

nothing is happening. This appears to support

the view that "you cannot relate advertising to

sales," since a good deal of advertising for these

brands occurred in this period.

This pattern, of minimal change in overall levels

from one period to another, is a common finding

in panel studies. However, if we start breaking

the total sample apart into its component groups,

we begin to find evidence that something is going

on. For example, if we break out those who are

exposed to advertising for these brands (any type,

either television or magazine) as compared with

those not exposed, we note an appreciable difi^erehce in their buying levels on the second wave:

20.5% va, 16.9%.

And going further, if we analyze the exposed

group by degree of exposure, we begin to see a

trend. The more units of advertising a group la

exposed to, the higher its buying level on Wave II

(where exposure to one medium at one period

equals one unit). By Wave II, there was a 42%

spread between the levels of the least-exposed and

most-exposed groups.

Changes in Exposure

One of the most useful features of true panel

data, where the same individuals are interviewed

over successive periods of time, is the opportunity

they afford for "dynamic analysis," the study of

change. The possibility of detecting significant

Journal of Marketing, July, 1963

relationships is enhanced when people are observed in the process of change.

In the present case, analysis of respondents in

terms of changes in their advertising exposure

revealed that changes in exposure were associated

with changes in buying. Respondents who experienced an increase in exposure (to either form of

advertising) showed an increased level of buying;

with no change in exposure, there was no change

in buying level; and with decreased exposure came

decreased buying. See Table 2.

The Increased Exposure group consisted of those

respondents who reported more units of exposure

on the second interview than on the first. The No

Change group were those who reported the same

numbers of units both times. The Decreased

Exposure group were those who reported more

units on Wave I than on Wave II; thus, at the

time they were more heavily exposed, their buying level was higher, and when they became less

exposed, their buying level became lower.

A Master Table presenting the detailed breakdowns of all results, together with the number of

cases in all subgroups, is given in Table 7, page

9. There the Increased Exposure groups have been

further broken down into groups C, I, K, L, and O.

The No Change groups are A, D, G, J, M, P. The

Decreased Exposure groups are B, E, F, H, N.

Buying Dynamics

Dynamic analysis may be applied to the dependent as well as the independent variable. Examination of the "buying dynamics" enables us not only

to measure changes in levels, but to perceive the

mechanism whereby these changes come about.

Those who were buying on Wave I can be divided

into two components. Some were still buying the

same brand on Wave II three months later; they

may be termed the "continue buying" group. Others

reported not buying this brand on Wave II; these

are the "stop buying" group.

Likewise, among those who were not buying the

brand on Wave I, some will be found buying it on

Wave II ("start buying") ; and others are still not

buying it ("nonbuyers").

Do these buying dynamics bear any relation to

changes in advertising exposure? They certainly

do, in a most interesting pattern—see Table 3.

Among those whose exposure to advertising increased, more people started buying than stopped.

TABLE 2

RELATIONSHIP OP BUYING TO

CHANGES IN ADVERTISING EXPOSURE

Increased exposure

No change in exposure

Decreased exposure

% Buying

Wave I Wave II

19.6

21.0

20.3

20.4

21.0

19.4

Relative

change

+7%

0

-8%

TABLE 3

BUYING DYNAMICS AND CHANGES IN EXPOSURE

Increased exposure

No change in exposure

Decreased exposure

% stop

buying

% con

tinue

buying

% start

buying

8.0

8.1

9^

11.6

|l2.2

11.6

|9.4

8.2

7.8

Indeed, this group showed the strongest tendency

of any of the three groups to "start buying." Those

with no change in exposure were marked by a

somewhat higher rate of "continuing" to buy. And

the most notable tendency among those with decreased exposure was to "stop buying"; in fact,

they stopped buying at a 20% greater rate than

they started. (Note that these figures are additive.

Checking back with Table 2, it will be seen that

the Stop plus Continue percentages add back to the

buying level on Wave I, while the Continue plus

Start figures add to the Wave II level.)

These relationships are highly suggestive of the

double functions of advertising: "generation" and

"preservation." Often advertising is thought of for

its value in inducing people to start buying a brand,

generating new customers; but the figures above

suggest its value additionally in persuading present

buyers to continue, thereby preserving old customers

and reducing the number of "lost customers."

Thus, in a situation where the overall buying

levels appeared static, it is seen that intriguing

dynamic changes—stopping, starting, switching—

were going on beneath the surface, and that these

buying changes had a meaningful relationship to

concurrent changes in advertising exposure. The

dynamic associations between shifts in exposure

and shifts in buying, while not "proof" of a causeand-effect sequence, strongly suggest an interrelationship between the two processes. They suggest

that advertising "works" and imply something of

"how" it works.

Relationships to Individual Media

Thus far the analysis has been in terms of exposure to advertising per se, regardless of type. It

may be useful to pursue this further, examining

some of the relationships to individual media.

The reminder is again in order that the following figures should be regarded as being of methodological rather than substantive interest. Their

purpose is not to represent a thoroughgoing attempt

at assessment of the relative effectiveness of the

two media, but simply to suggest some of the possible analytical approaches for such comparisons.

A number of limitations in the present study prevent it from being considered a full-scale inter-

A Pioneering Experiment in Assessing Advertising Effectiveness

media comparison: the study is restricted to a

single market; it covers only two types of advertising, without reference to other media which may

have been used; the measures of exposure and buying are on a verbal-report basis, without verification by pantry-checks or more elaborate audiencemeasurement techniques; no attempt has been made

to relate results to the costs of advertising; and the

study covers only a cumulative series of exposures,

making no effort to determine the effects of a single

advertisement or single broadcast, nor to assess the

effects of varying frequencies of exposure.

Some of these limitations have been successfully

attacked in other studies by the National Broadcasting Company.^ They are not insurmountable in

future research, but their presence should be kept

in mind.

"Before" and "After" Exposure

With tbese cautions in mind, it is of interest to

examine some of the ways in which a 2-wave panel

survey can be analyzed to yield indications of media

effectiveness.

The most interesting analyses are those whieb

take advantage of "turnover," that is, the changes

which are continually going on in the audience to

any medium. Here we apply to audience the same

kind of "dynamic analysis" previously applied to

the buying process.

Let us start with the population of people not

exposed to a given medium (for example, a television program) at the time of the first survey. These

same individuals can then be followed through on

Wave II. Thanks to the phenomenon of audience

turnover, it will be found that some of them were

in tbe exposed category at the time of Wave II

(that is, they have "begun viewing").

This is a particularly significant group, because

they provide cases on which we now have buying

records "before" and "after" exposure. And since

The Advertising Impact of TV Specials (New York:

National Broadcasting Company, Inc., 1957). Hardgoods and the Impact of Television (New York:

National Broadcasting Company, Inc, 1960). Introducing New Cars on Television (New York:

National Broadcasting Company, Inc., 1960).

tbe group is made up of precisely tbe same people

both times, all variables of a personal and demographic nature which might influence the buying

process are held constant.

Similarly, the remaining segment of the population not exposed on Wave I is a very useful group:

they comprise the people who did not "begin viewing," thus serving as a control for those wbo did

begin viewing.

The comparison of these two groups is especially

significant in that botb of them came from the

same population on Wave I. Starting from the

same condition of nonexposure, we can then follow

them as one group becomes exposed and the otber

does not—what happens to their buying?

Table 4 shows these buying levels. Taking, for

example, the case of television viewing, tbe first

two lines give the ieveis for all those who were not

exposed on Wave I. Of these, the ones who "began

viewing" showed an increase of 10% in the number

buying the brand advertised on the program they

began viewing (again, this is the average of 22

brands, each tabulated against the viewing of its

own program). Those who also started as nonviewers but remained nonviewers showed no change

in buying.

Tbe converse of the foregoing analysis is also of

interest. If we start with all those who were exposed to a given medium on Wave I and trace

them through, we find that audience turnover occurred in this group also. Thus, some of the group

were in the exposed category on Wave II as well as

on Wave I (that is, they "continued viewing").

And others were in the nonexposed grOup the second time (they "stopped viewing").

So again we have available two subgroups derived from the same Wave I population. Both were

viewers (or readers) at a given point in time. Some

continued, and some did not. What happened to

their buying behavior?

Certain hypotheses can be formulated as to what

might be expected under these conditions. Given a

group which is exposed to begin with, and continues its exposure, it would be a reasonable hypothesis that if advertising is effective, such a group

should show a high initial level on the first wave

TABLE 4

"BEFORE" AND "AFTER" EXPOSURE TO SPECIFIC MEDIA

% Buying

Wave I

Television: Nonviewers who . . .

. . . became viewers

. . . remained nonviewers

Magazine: Nonreaders who . . .

. . . became readers

. . . remained nonreaders

Wave II

Relative

change

18.7

18.0

20.6

18.0

-M0%

20.5

19.2

21.0

19.8

+3%

+3%

0

Journal of Marketing, July, 1963

TABLE i5

MAINTAINING VERSUS REDUCING EXPOSURE TO SPECIFIC MEDIA

9;? Baying

Wave II

Wave I

Television: Viewers who . . .

. . . continued viewing

. . . stopped viewingMagazine: Readers who . . .

. . . continued reading

. . . stopped reading

(associated with its Wave I exposure) and maintain this high level on the second wave (in keeping

with its sustained exposure). As shown in Table 5,

this is in fact what happened in the case of the

viewing group.

Similarly, the hypothesis would be that a group

which is initially exposed, but subsequently ceases

its exposure, should again start at a high level

(under the condition of exposure) but drop to a

lower level (when no longer exposed). This, too, is

what happened to the viewing group.

This phenomenon of a drop in buying level associated with a reduction in advertising exposure distresses some in the advertising field, on the ground

that it seems to have "negative" implications. Quite

to the contrary, it is important evidence of advertising effectiveness.

If one hypothesizes that buying levels should

rise under increasing advertising pressures and remain high under continuing- pressures, then he

must also hypothesize that under decreasing pressures, they will fall. The latter is a necessary corollary of the former. And the more effective is the

medium, the greater should be the decline if its

pressure is reduced. Consequently, in investigating

the effectiveness of advertising this test rounds out

the full circle of testable hypotheses.

Indeed, as a practical matter, if this did not

prove to be true, why should anyone, once he had

achieved a satisfactory level, continue to advertise?

A 16-Fold Analysis

The above analysis is capable of still further

improvement. Each medium was treated above as

though it were independent of the other. But in actual fact some of the "viewers" were also "readers,"

and some of the "readers" were "viewers." Hence,

the analysis must cope with the phenomenon of

audience duplication.

Possible Advertising Strategies: A Model

To approach the problem systematically, let us

start by laying out all the possible conditions which

may be encountered in dealing with two different

media at two different points in time.

Taking one of the media first (for example, maga-

23.0

21.6

23.2

19.2

21.7

19.9

20.9

19.4

Relative

change

+ 1%

-11%

-4%

zines), there are four—and only four—conditions

of exposure which can obtain across two points in

time. Using a plus sign to signify exposure and a

minus sign for nonexposure, the four possibilities

are:

f- Not exposed on I, exposed on II

("start reading")

+ -\- Exposed on both occasions

("continue reading")

+ — Exposed on I, not on II

("stop reading")

~ — Not exposed either time

("non-reading")

The same four exposure groups—and no more—

can be laid out for the other medium. We have

already examined these four groups for each medium taken separately (Tables 4 and 5).

But when the two media are considered simultaneously, it is evident that there are 4 times 4, or 16,

possible exposure conditions. In conjunction with

each one of the TV groups (for example, "start

viewing") it is possible to have any one of the four

magazine-exposure situations ("start," "continue,"

"stop," or "no" reading), and vice versa.

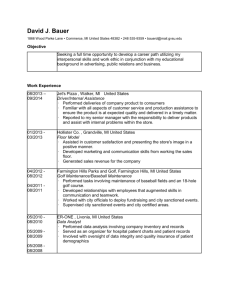

These 16 possible situations are represented in

Figure 1. An intriguing aspect of this chart is that

it also turns out to be a systematic layout of all the

possible advertising strategies that could be followed—a "model," as it were, of all the possible

decisions which could be made by an advertising

manager under the restriction of two media at two

points in time.

The data from a 2-wave survey can be analyzed

according to this model. Since each respondent will

be found to fall into one, and only one, of the 16

exposure groups (and these 16 groups account for

all respondents), the 16 groups can be broken out

and their buying levels and changes tabulated.

For completeness, this "master table," setting

forth the full results of the present survey, is shown

in Table 7. However, in the interests of simplicity

some of the more meaningful comparisons are presented for easier examination in Table 6. Each

group in Table 6 is keyed by letter to the corresponding line in Table 7.

A Pioneering Experiment in Assessing Advertising Effectiveness

Magazine Compaign

_

I

Start

start

Both

-+ +StortTV

Keep Mag.

+ + - + + -I- + +

S

Keep TV

Start Mag.

Continue

Switch from

Mag. to TV

Switch from

TV to Mag.

__ __

„

^

Keep TV

StopAlag.

No TV

Start fAag.

None

FIGURE

5top

Both

Stop TV

KeepA\ag.

-"

-I- +

No TV

Keep Mag.

Start TV

No fAa^.

++ +- + +

Keep

Both

+ - + + + - -HStop

None

+-

-+ - +

„ , , I.

Stop

Continue

Start

_

.^

Keep TV

No Mag.

+Stop TV

No Mag.

1, .

No TV

Stop Mag.

No

Advg.

1. Possible advertising strategies: A model-

Possible Advertising Strategies:

Their Relationship to Buying

Following are some of the more interesting comparisons which can be drawn from the complete

breakout of results of such a 2-wave, 2-media survey. Such comparisons not only take proper account

of but even take advantage of the duplication and

nonduplication between media, as well as of the

changes in exposure to the media (stops, starts,

and switches) in order to raise for examination

various hypotheses regarding the effectiveness of

advertising in general, and of the two media in

particular.

To render the exposure symbolism somewhat

more meaningful, each of the groups is tagged with

a descriptive phrase indicating the "advertising

analog" which it represents. Thus, each group can

be thought of as representing, in a sense, a "simulation" of an interesting advertising strategy. However, there are definite limitations to such analogies, in that here the exposure-condition is brought

about by self-selection on the part of the respondent, rather than having been experimentally imposed from without by the investigator.

Moreover, the principal focus is not on the substantive content of the figures themselves, which

represent only the findings of a single study done

a few years ago in a single market, but on illus-

trating one possible approach to the investigation

of advertising effectiveness and intermedia comparisons.

For each group in Table 6 are shown the buying

levels on Waves I and II and the change from I to

II, plus the "buying dynamics" which generated

these levels. As a visual aid in noting points of

special interest, all comparisons showing a spread

of 2 or more percentage points are enclosed.

Thus, in the first comparison the most noteworthy difi'erence is that the group exposed to

TV-only both times showed an unusually high

"continue-buying" rate, plus a higher "start-buying" rate than the magazine-only group. However,

in the second comparison the group which switched

from TV to magazine exposure showed more "continue-buying" than those who switched from magazine to TV exposure.

By pairing the appropriate groups, it is possible

to set up a comparison in which one medium remains constant, while the other is varied. Comparison 3, for example, brings together the two groups

who maintained exposure to one medium while reducing exposure to the other. Reduced exposure to

TV seemed to have more effect on the buying level

than reduced magazine exposure; this resulted from

the fact that with reduced TV went a lower rate of

"starting" to buy and a higher rate of "stopping."

Journal of Marketing, July, 1963

TABLE 6

EELATIONSHIPS OP POSSIBLE ADVERTISING STRATEGIES TO BUYING

Group TV

Magazine

1

Advertising analog

1. A continuing campaign in a single medium

D

+ +

A continuing TV-only campaign

M —_

+ +

-A. continuing Magazine-only campaign

2. Switching campaigns from one medium to another

Switch from Magazine to TV

J

- + -]—

G + - + Switch from TV to Magazine

3. Dropping a cwm-paign

B

- ! - + + _

Keep TV but drop Magazine

Keep Magazine but drop TV

E

-H + -H

4. Starting a campaign

O

++ Start Magazine campaign, no TV

L - +

• — Start TV campaign, no Magazine

K

- 4- - -1-1- Start campaign in both

5. Extremes of change in advertising strategy

K

— •\- — -f

Start campaign in both media

F

+ — + _

Drop all advertising

6. Extremss of advertising weight

A

+ +

+ 4 - Continuous advertising in both media

P

No advertising in either

Comparison 4 presents the reverse case, comparing the two groups who remained nonexposed to one

medium, while increasing, their exposure to the

other. Increased exposure to TV seemed to have the

greater effect, due chiefly to the greater rate of

"start-buying" in this group. However, the greatest change of all is observed in the group which

increased exposure to both media. Here the buying

level increased markedly, again principally as a

result of more "start-buying."

Comparison 5 contrasts the extremes of change

in advertising exposure, comparing those who

"started" both media with those who "stopped"

both. When both media were working together the

"starts" went up (due to high "start-buying"),

and the "stops" went down (due to high "stopbuying").

The final comparison contrasts the extremes of

advertising pressure: full exposure to both media,

compared with absence of exposure. Here, witb

relatively constant advertising exposure, one does

not hypothesize change in buying, but differences

in levels of buying. And that is what happened. The

continuously exposed group was buying at a continuously higher level—and the difference was due

to their much higher rate of "continuing to buy,"

with this group showing the highest percentage of

"loyal customers" of all 16 exposure groups.

Thus, the analysis seems to "make sense," and to

document the value of advertising in terms which

management could readily appreciate. Although on

% buy brand

//

Change

Buying dynamics

Continue

Stop Start

21.8

19.3

23.0

18.7

1.2

-.6

14.2

11.9

7.6

7.4

8,8

6.8

18.6

22.5

18.8

20.8

.2

-1.7

9.4

12.4

9.2

10.1

9.4

8.4

22.2

23.2

23.0

19.8

-3.4

13.8

12.7

8.4

10.5

9.2

7.1

17.7

18.1

17.6

18.0

20.9

21.7

.3

2.8

4.1

9.9

11.1

10.2

7.8

7.0

7.4

8.1

9.8

11.5

17.6

19.7

21.7

17.6

4.1

-9.A

10.2

9.9

7.4

9.8

11.5

7.7

23.7

16.0

24.0

16.9

.9

16.1

9.3

7.6

6.7

7.9

7.6

.8

an overall, total-sample basis the buying levels

appear to remain static and little seems to be

happening, on breaking out the interrelationships

between exposure and buying, it is found that

movement and change is going on.

And these changes relate to advertising exposure

in meaningful ways. Under increasing exposure,

more people start buying, and buying levels rise.

Under decreasing exposure, more stop buying, and

buying levels fall. Under continuing' advertisingpressure, more continue buying, and levels remain

high. And finally, different media can be examined

to see which are associated with these effects to a

greater and which to a lesser degree.

Further Improvements Desirable

We have carried the analysis of this case-history

through several successive levels of refinement, each

of which has considerably improved it. However,

the process of improvement is not by any means

complete.

The fundamental objective in all "effects" comparisons is to confront what did happen in a given

circumstance (for example, under the influence of

a given advertising strategy) with what would have

happened, if that circumstance had not obtained.

The difference, all other things being equal, is the

"effect" of that circumstance. Since the "did happen" is known, the problem is always to find the

"would have happened."

In the present case, for example, there may still

A Pioneering Experiment in Assessing Advertising Effectiveness

TABLE 7

MASTER TABLE, SHOWING COMPLETE RESULTS FOR BOTE[ WAVES*

Exposure

Group TV Magazine

24.0%

23.0

23.3

23.0

16.1%

13.8

13.7

14.2

23.2

Keep Magazine, drop TV

Drop all advertising

19.7

Substitute Magazine for TV campaign 22.5

No Magazine, drop TV

21.0

19.8

17.6

20.8

18.5

12.7

9.9

12.4

11.3

10.5

9.8

10.1

9.7

7.1

7.7

8.4

7.2

70

55

49

147

7.8

9.4

11.5

9.8

60

39

56

137

analog

A

E

C

D

-j- -{-

+

-t—

—

+

—

+

—

Continuous advertising in both media

Keep TV but drop Magazine

Add Magazine to TV campaign

Continuing TV-only campaign

E

F

G

H

-f —

+

-f

—

—

+

—

+

—

I

J

K

L

^

M

— —

N

0

P

23.7%

22.2

24.2

21.8

+ +

-1

— +

— —

Add TV to Magazine campaign

Substitute TV for Magazine campaign

Start campaign in both media

Start TV-only campaign

20.5

18.6

17.6

18.1

21.0

18.8

21.7

20.9

13.2

9.4

10.2

11.1

7.3

9.2

7.4

7.0

+

+

—

—

Continuing Magazine-only campaign

No TV, drop Magazine

Start Magazine-only campaign

No advertising in either

Total (weighted)

19.3

18.8

17.7

16.0

19.4%

18.7

18.2

18.0

16.9

19.6%

11.9

10.4

9.9

9.3

11.5%

7.4

8.4

7.8

6.7

7.9%

+

—

-i—

Start No. in

Stop

buying

7.6%

8.4

10.5

7.6

Advertising

% buy' brand Continue

Wave I Wave II buying

buying

1.9%

9.2

9.6

8.8

6.8

7.8

8.1

7.6

8.1%

group

158

86

101

290

228

151

197

617

2441

* Each figure is the average of the corresponding figures for 22 different brands.

remain some variance between the groups being

compared, due to differences in their composition

and makeup (that is, "all other things" are not yet

equal). In the search for further methodological

improvement in future studies, one of the most

promising, tools with which to attack this problem

might be multiple regression analysis, with large

numbers of variables handled simultaneously.

Implications

It was our initial thesis that there are two basics

in advertising, reach and impact.

The significance of this observation, however,

goes well beyond the mere naming of two factors.

If each of these factors could be measured and reduced to a number, and if these two numbers were

multiplied together, the resulting product would

be a third number which would have the highly

significant property of being a true measure of the

total effectiveness of the advertising in question.

Thus, the two factors of audience and impact

represent far more than simply different emphases

in evaluating advertising. They represent the two

necessary and sufiicient conditions for performing

a true measure of advertising effectiveness.^ As

such, they are capable of formulation in a simple

but powerful equation. The total effectiveness of

advertising is the product of size of audience multiplied by impact per member of the audience:

E = A X I

See Thomas E. Coffin, '"Total Effect' Concept in

Media Comparisons," Media/scope Vol. 3 (February, 1959), pp. 44-48 and 52.

This equation is applicable both to the problem

of measuring the effectiveness of any single advertisement or campaign, and to that of properly comparing different advertising media. In the latter

application, it effectively solves the "apples-andoranges" dilemma in media comparison.

It is indeed true that a "reader" and a "viewer"

may be worth different values and should not be

compared. But if the impact per reader could be

measured, and multiplied by the number of readers,

the product would represent the total effect of the

reading. By putting each medium through the same

process, all would be converted to the same terms

and become comparable. Thus, the end-products of

the effectiveness equation are comparable, although

the separate components are not.

The effectiveness equation also has the property

of being self-adjusting for differences in the level

at which the audience factor is measured. Thus, if

a "loose" definition of audience is used, audience

size will be large; but due to the inclusion of many

"lightly-exposed" people, the impact per person will

be small. The product of these two will be similar

to that obtained from a "tight" definition, yielding

a smaller audience but a correspondingly higher

impact factor. Since a key problem in the comparison of media has been how to define their audiences

with equal "tightness," this self-adjusting property

of the effectiveness equation is a major benefit.

A great deal remains to be done, of course, before

such an ideal procedure can become a matter of

daily practice. "Audience times impact" yields a

true measure of total effectiveness, but the precision

10

Journal of Marketing, July, 1963

of final figure is a direct function of the precision

with which each of its components is measured. At

present, the precision of audience measures far exceeds that of impact measures.

The advertising industry has been spending most

of its research dollars in measuring the audience

component, with the result that we can now measure this dimension reasonably well. It is now time

to start spending more dollars in pursuing the

measurement of impact, for it is this area which

in the future promises the greatest improvement of

overall efficiency in advertising evaluation.

MARKETING MEMO

Factors Leading To Inventiveness . . .

Inventiveness appears to emerge from situations where personal and social conditions of the following types are encountered: high drive (ambition); frequent marginalism; high relationism; and high operationalism. By high drive is meant that

cultures and individuals of high inventiveness make strong demands of their environment, have high hopes and expectations,

and value persistence in endeavors. By frequent marginalism, we

mean that uncommon views, deviant personality types, and conflicting Weltanschauung are endemic in the inventive culture and

express themselves through inventive individuals. Relationism

is defined as the ability to perceive connections of all kinds among

things and events; it is needed in greater degree for newly combining relations, the salient feature of the invention. High operationalism denotes the strong tendency to regard fulfillment of an

idea as requiring- its expression in activity.

—Alfred de Grazia, "Elements of Social

Invention," The American Behavioral

Scientist (December, 1961) p. 8.

Reprints of every article in this issue are available (as long as supply lasts) at

the following prices:

Single reprint

Two reprints

Three reprints

$1.00

1.50

l.SO

Four to 99, each

First 100

Additional lOO's

$ .50

40.00

20.00

Quantity Discount

Special prices for large quantities.

Send your order fo:

SAMUEL N. TURIEL & ASSOCIATES, INC.

333 North Michigan Avenue, Chicago 1, liiinois

Duplication, reprinting, or republication of any portion of the JOURNAL OF

MARKETING is strictly prohibited unless the written consent of the American

Marketing Association is first obtained.