Inflationary cosmology

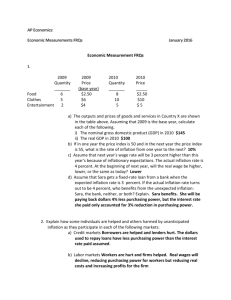

advertisement