THE BREAKOUT OE CHINA-INDIA STRATEGIC RIVALRY IN ASIA

advertisement

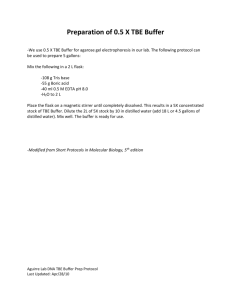

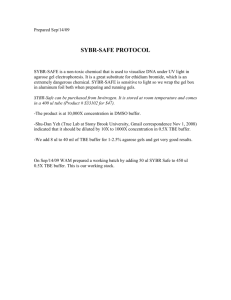

THE BREAKOUT OE CHINA-INDIA STRATEGIC RIVALRY IN ASIA AND THE INDIAN OCEAN Francine R. Frankel Submerged tensions between India and China have pushed to the surface, revealing a deep and wide strategic rivalry over several security-related issues in the Asia-Pacifie area. The U.S.-India nuelear deal and regular joint naval exercises informed Beijing's assessment that U.S.-India friendship was aimed at containing China's rise. China's more aggressive claims to the disputed northern border—a new challenge to India's sovereignty over Kashmir—and the entry of Chinese troops and construction workers in the disputed Gilgit-Baltistan region escalated the conflict. India's reassessment of China's intentions led the Indian military to adopt a two-front war doctrine against potential simultaneous attacks by Pakistan and China. China's rivalry with India in the Indian Ocean area is also displacing New Delhi's influence in neighboring countries. As China's growing strength creates uneasiness in the region, India's balancing role is welcome within ASEAN. Its naval presence facilitates comprehensive cooperation with other countries having tense relations with China, most notably Japan. India's efforts to outflank China's encirclement were boosted after Beijing unexpectedly challenged U.S. naval supremacy in the South China Sea and the Pacific. The Obama Administration reasserted the big picture strategic vision of U.S.-India partnership first advanced by the nuclear deal. Rivalry between China and India in the Indian Ocean, now expanded to China and the United States in the Pacific, is solidifying an informal coalition of democracies in the vast Asia-Pacifle area. T he past few years have seen a dangerous rise in mutual suspicion between India and China, propelling bilateral relations toward a deep and wide strategic rivalry. This article examines the security issues that have led to the open breakout of competition between India and China long implicit in their geographical proximity and their great power ambitions in neighboring areas and the Indian Ocean. New Delhi's perspective of Chinese policies that aim at the strategic encirclement of India, as well as Beijing's outlook on India's attempt to limit China's influence in South and Southeast Asia and its power projection into the Indian Francine R. Frankel is professor of political science and founding director of the Centerfor the Advanced Study of India (CASI) at the University of Pennsylvania. Journal of International Affairs, Spring/Summer 2011, Vol. 64, No. 2. © The Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York SPRING/SUMMER 2011 | 1 Francine R. Frankel Ocean, has overridden tbeir formulaic statements of shared interests as partners in strengtbening a multipolar world. Tbe new reality of rivalry is evident from tbe following security issues: (1) tbe escalation of the Sino-Indian border dispute; (2) tbe deepening of the strategic alliance between Cbina and Pakistan; (3) Cbina-India rivalry in Soutbeast Asia and tbe Indian Ocean; and (4) India's "Look East" policy to promote bilateral ties witb other countries that bave tense relations with China in the region, not least, tbe United States. New Delhi's china's long-standing dismissive attitude toward ivP of India's capabilities and great power ambitions was . shaken when tbe Bush Administration began prostrategic tracted negotiations with India in 2005 for entering encirclement into a long-term strategic partnersbip, sbortly after of India has tbeir defense ministers signed tbe bilateral New Framework for tbe U.S.-India Defense Relationsbip,' Tbe U.S.-India nuclear deal, approved by Washington and New Delbi in 2008, carved out an exception statements of for india from American law prohibiting commerce shared interests ^^ ^^^^^ nuclear energy with a non-signatory of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Tbe last i minute push of tbe Busb Administration to gain a an unconditional exemption for nuclear commerce world. with india from tbe Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) exacerbated China's suspicions tbat closer U.S.-India friendsbip was aimed at containing Cbina's rise. Between 2002 and 2010, India and tbe United States carried out fifty joint military exercises. Since 2008, India bas signed arms deals witb tbe United States worth $8,2 billion,^ Cbina's Ministry of Foreign Affairs pressed India for an explanation, even suggesting tbat an Asian NATO was in tbe offing. Tbis exaggerated response coincided witb a much more aggressive Chinese claim to the disputed northeast border along tbe McMabon Line on tbe Himalayan frontier and the Line of Actual Control (LAC). Bilateral agreements in 1993 and 1996 to demarcate the LAC and diminisb tbe prospect of border clashes similar to those tbat preceded tbe 1962 India-Cbina war bave yet to be implemented. Indian officials acknowledged in December 2009 tbat over a twenty to twentyfive year period, Chinese incursions across India's borders had resulted in tbe loss of a "substantial" amount of land along the LAC.^ Tbe precise area claimed by Cbina is unclear without Cbina having offered India official maps of tbe eastern sector. Cbina's vice minister of foreign affairs and otber senior officials defined Beijing's claim in 2001 as 125,000 square kilometers in the eastern sector, and tbe 2 I JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The Breakout of China-India Strategic Rivalry in Asia and the Indian Ocean area of "real conflict" as 95,000 square kilometers south of the McMahon Line."* A leading Indian security expert refers to China's occupation of nearly 48,000 square kilometers of Indian territory in the western sector of Aksai Chin in Ladakh, in addition to China's claims of 94,000 square kilometers in the eastern sector, the bulk of which forms India's state of Arunachal Pradesh, shown as part of China on its maps.^ A new challenge to India's sovereignty arose in August 2010 in the disputed western sector. Pakistan allowed between 7,000 and 11,000 Chinese troops to enter Pakistan-administered Azad (Free) Kashmir, referred to by India as Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir, or PoK, and the disputed Gilgit-Baltistan region to assist in the construction of a high-speed rail and road link from eastern China to the Chinese-built naval port of Cwadar in Baluchistan, east of the Persian Culf.^ Financed mainly by low-cost loans from China's Exim Bank, infrastructure projects to widen the Karakoram Highway and link roads, extend rail lines, construct bridges and hydropower dams and expand telecommunications coverage employ about 122 Chinese companies.^ China's renewed claims and its growing economic presence in PoK elicited sharp criticism from the Indian strategic community and the press, which in turn provoked combative responses from China. A senior Indian national security expert characterized Chinese protests in 2009 as a démarche, warning India not to forget 1962 and China's ability to occupy "southern Tibet." When Prime Minister Manmohan Singh countered China's aggressive stance by visiting Arunachal Pradesh during the state assembly elections in mid-October 2009, the Chinese foreign ministry made known that Beijing was "seriously dissatisfied." India's external affairs minister immediately restated the government of India's fixed position that Arunachal Pradesh is an integral part of India.^ This point was dramatized by permitting the Dalai Lama to visit the Tawang monastery in Arunachal Pradesh, the birthplace of the sixth Dalai Lama in the 17th century, and as the question builds about selecting a successor to the fourteenth Dalai Lama, a possible place to identify the next incarnation of Tibet's spiritual leader. China's legitimate rule over Tibet, after it was forced to become a part of China in 1950, continues to be questioned as Beijing increases the migration of Han Chinese to the region, and undermines Tibetan culture through bilingual educational reform that will make Mandarin Chinese the medium of instruction in primary schools by 2015, with Tibetan as a supplementary language.' The Dalai Lama, along with the more than 90,000 Tibetan refugees living in India, asserts his religious authority over all Tibetans. Traveling abroad and speaking up for the preservation of Tibetan culture, he keeps alive China's persistent concern that India could play the "Tibet card" to encourage uprisings in favor of Tibet's SPRING/SUMMER 2011 13 Erancine R. Erankel autonomy like those of 2008 in Lhasa. China's "core interest" lies in preserving full sovereignty over the resource-rich Tibetan plateau, without which "China would be but a rump and India would add a northern zone to its subcontinental power base."'" ESCALATION OF THE CONFLICT The China-India border dispute took on the character of a broader strategic conflict when the People's Daily attacked the stiff Indian position as evidence of "recklessness and arrogance" toward its neighbors. O n e current threat ^^^ near."" In a follow-up article, the People's Daily attributed New Delhi's intransigence to the notion ^j^^^ ^^g United States viewed India as a counter- ., tnat t J 1 and a foreign poUcy of "befriend the far and attack it, I COUiQ t a K e in 48 " weight to China and was willing to feed India's ambitions with arms sales. It repeated the warning that if India did not practice restraint "an accidental slip or go-off at the border would erode into a war."'^ The most pronounced recent pressure on New Delhi by Beijing derives from modification of the position it adopted in 1996, when former Chinese president Jiang Zemin signalled that the Kashmir issue should be settled by negotiations between India and Pakistan. India was unprepared for the Chinese government's refusal in 2008 to issue official stamped visas to Indian travelers from both Kashmir and Arunachal Pradesh, instead stapling entry papers to Indian passports. The government of India, which had earlier yielded to Premier Wen Jiabao's insistence in 2007 on a statement using the word "strategic" to describe India-China relations and agreed to regular high-level visits and bilateral defense exercises, informed China in October 2010 that no further defense talks would be held until China respects India's territorial sovereignty over Kashmir and grants official visas to Indian officials.'^ Informal discussions between China's foreign minister Yang Jiechi and India's external affairs minister S. M. Krishna in Wuhan in mid-November 2010 brought no change in China's policy and sharpened India's position. India, for the first time, drew a direct parallel between China's core concerns over Tibet and Taiwan and India's core concern over Jammu and Kashmir.''' One month later, Chinese premier Wen Jiabao, during his December 2010 visit to India, indirectly dismissed New Delhi's security concerns. Reverting to language frequently used in the 1950s, he called the boundary dispute a "historical legacy" that would not be easy to resolve and would "take a fairly long period of time."'^ The realities are that the border dispute will not be resolved through negotia- 4 I JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The Breakout of China-India Strategic Rivalry in Asia and the Indian Ocean tions in the foreseeable future. China's scarcely veiled warning of using its superior infrastructure of improved roads, rail and airfields on the Tibetan side of the border for rapid deployment of fighter aircraft and bulked up border defense troops is a stratagem of intimidation suggesting willingness to resort to its active defense strategy for fighting local wars with high-technology weapons. One current threat assessment suggests that China, with its well-equipped Rapid Reaction Forces, including airlift capacity, light weapons and high-tech communications equipment, could "take Arunachal in 48 hours."'* Memories ofChina's totally unexpected 1962 inva"-pi, T J « sion after a similar impasse in negotiations between A l i e lliu.la.ll Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Premier Zhou defense minister Enlai led India to take China's tough talk very seriasked the ouslv. The notion that India should not be seen in r , .. . , ^,. c • '•• •^. ' • competition with China ror another generation gave way to a new urgency in preparing the basics of a long-term strategy to manage xhallengès to its territorial, economic and energy interests. forces to prepare ^ ^ lOÏ" " tWO-irOnL war âPainSt China. anrl A TWO-FRONT MILITARY DOCTRINE The most significant change in India's assessment of China's intentions was demonstrated in the 2008 set of directives by the Indian defense minister to the armed forces asking them to preparé for a "two-front" war against China and Pakistan.''' This doctrine accords with the long-held belief of India's defense analysts that China is following a protracted strategy of containing India in the subcontinent, and that the core of this strategy revolves around the China-Pakistan alliance. The two-front doctrine requires the Indian Army, currently at I.I million men, to achieve combat superiority over Pakistan, and to deter, or if necessary defend, against an attack from China in the medium or long term, protecting India's extended geopolitical interests in the Indian Ocean region. In June 2010, India started work on a long-delayed project to build a 5-mile tunnel through the Pir Panjal mountain range. The tunnel is designed to bypass the dangerous Rohtang Pass in order to provide an all-weather route for supplying India's tens of thousands of army troops in strategically important remote regions, including mountain peaks close to Aksai Chin and the Siachen Glacier, areas contested by India and Pakistan.'^ The Indian Army is preparing to meet the threat of a possible two front war with China and Pakistan by raising four additional mountain divisions for a mobile strike corps of 64,000 troops that can move quickly over the Himalayas to attack in the northeast and northwest simultaneously.'^ Force requirements for the SPRING/SUMMER 2011 15 Francine R. Frankel Indian Air Force in order to neutralize Pakistan in a full-scale war and dissuade China from intervention are 44 squadrons, according to the defense ministry's Eleventh Plan, 2007-2012. This number rises to 55 squadrons to defend against simultaneous attacks by China and Pakistan.^^ The Indian Air Force, down to 32 squadrons from a sanctioned force of 39.5 combat squadrons, is reported to be building up its strength to 45 combat squadrons.^' The success of efforts to modernize India's land forces is dependent upon its acquisition of state of the art mechanized weapons platforms, artillery guns, air defense guns, guided missile systems, weapon locating radars, battlefield informadefense tion management systems, as well as weather surveilP at lance and night-fighting capabilities.^^ Q Q A buildup of this magnitude will stretch India's Z percent to ó resources for years ahead. During 2009-10 India's percent of its defense expenditure was 2.3 percent of its GDP is i n U . S . (against a ceiling of 3 percent), and projections to ovrvio r^r^vc 2014-15 show a decline in the defense share of GDP to less than Z percent."'^ Chma s defense spending, at than three times 2 percent to 3 percent of its GDP, is in U.S. dollar t h e size o f India's. terms more than three times the size of India's. Estimates of military expenditures by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) for 2009 in constant 2008 dollars places China in second place with an expenditure of close to $100 billion and India in ninth with an outlay of over $36 billion.2'' India's expenditure is focused on enhancing the operational capability of the Indian Army, integrating reforms in procurement and making command structure changes to create a lethal, agile and networked force, strengthened by air defense and deep strike capability rockets and cruise missiles, to meet challenges from Pakistan and China on both the western and eastern fronts.^' Gurmeet Kanwal, director of the Center for Land Warfare Studies in New Delhi, cites a recent KPMG report that states India is likely to spend up to $100 billion over the next ten years on purchases of military equipment. About 250 light helicopters, 1,500 howitzers, marine reconnaissance aircraft, "Super Hercules" transport aircraft and heavy lift aircraft for its Special Forces are in the pipeline.^* India is also committed to building a powerful naval presence in the Indian Ocean. It is constructing an indigenous aircraft carrier and has approved one more. Its first indigenously built nuclear-powered submarine, Arihant, was launched in July 2009; two more are being built. The Arihant is armed with fifteen missiles capable of delivering nuclear warheads at a range of 750 kilometers, to be replaced in the future with missiles having a 3,500-kilometer range.^^ China currently has 6 I JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The Breakout of China-India Strategic Rivalry in Asia and the Indian Ocean tbree nuclear powered ballistic missile submarines and is expected to build three more, each with twelve missiles and a range of more tban 7,200 kilometers (about 3,888 nautical miles),^^ India does not need to match Cbina, which tbe Pentagon believes aspires to displace U.S. influence in tbe Pacific. Wbat India does bave to do, as strategic affairs analyst C. Raja Mohan argues, is demonstrate its policy commitment and expanded capabilities for power projection far beyond India's sbores.^^ Navy officials are confident about the future. Tbey plan to bave two aircraft carrier strike groups by 2015, tbree by 2022 and expect to build or acquire six new submarines and tbirty-one new warships. Seven frigates will be equipped with state-of-the-art Aegis integrated combat systems.^" Nevertbeless, tbe current naval balance, using publisbed sources, sbows an advantage for Cbina in most categories. China is building its first aircraft carrier and may build a total of six over tbe coming years. Its submarine force totals sixty-two, including six nuclear powered attack submarines, three nuclear powered ballistic missile submarines and fifty-tbree diesel-electric submarines, and is expected to increase to about seventy-five submarines over tbe next ten to fifteen years. India's submarines, counting tbose being built, total about eigbteen. Cbina's destroyers and frigates bave increased at a remarkable rate and many have advanced anti-air warfare capability similar to tbe U.S.-made Aegis combat system,^' Cbina's destroyers and frigates total about thirty-five, compared to India's combined number of thirty-three, about fifteen of wbicb are still in the approved, trial or building stage.^^ T H E CHINA-PAKISTAN NUCLEAR PARTNERSHIP Concerns about India's military modernization plans will be discounted to some extent by Cbina's all-embracing relations with Pakistan. Tbe Beijing-Islamabad "proliferation nexus" began in tbe early 1980s wben Cbina provided Pakistan witb a tested blueprint of a 20-kiloton nuclear bomb, along witb weapons-grade uranium for two bombs, neutron initiators and otber materials.^^ In the 1990s, tbe Cbinese government transferred M-9 and M-11 ballistic missiles and components for the Sbabeen family of intermediate range ballistic missiles, while facilitating tbe acquisition by Pakistan of Nodong missiles from Nortb Korea. China's motive in assisting Pakistan's missile program was first and foremost aimed to "[belp] Pakistan balance India and [create] local nuisances tbat would keep India from becoming more than a bamstrung regional power."^'' In tbe 1990s, Cbinese nuclear assistance to Pakistan, witb the construction of a 40-megawatt (MW) unsafeguarded tbermal heavy water reactor at Kbusab to generate weapons grade plutonium, and its supply of tbe 300 MW pressurized water reactor (PWR) at Chashma, gave Pakistan tbe technological capacity to SPRING/SUMMER 2011 I 7 Erancine R. Frankel produce small, light and more powerful warheads that can be fitted to strategic 500-kilometer range cruise missiles under production and aimed at India. When China became a member of the NSG in 2004, it successfully claimed the right to build a second PWR at Chashma under the NSG's "grandfather" provisions by asserting Chashma 2 was covered under the earlier nuclear agreement with Pakistan. The Chashma 2 nuclear power plant, adjacent to the Khusab site, will be able to produce enough plutonium for forty or fifty nuclear weapons a year.^^ China continued its support to Pakistan's nuclear capabilities in March 2010 U.S. intelligence assessments in when one of Beijing's state companies signed an agreement to supply chashma 3 and 4, two PWRS of ^^^ ^ ^ capacity, arguing the sales were also "grand- y oni 1 January ZUl 1 fathered" by the agreements to build Chashma 1 and 2. Nuclear experts rejected this rationale as a "blatant COnclUd.eCl t h a t Pakistan has deployed nuclear disregard of international guidelines."^'' At the June ^^^^ meeting of the NSG in New Zealand, the United states urged China to get a formal exemption ^ ^ from the NSG for its sale to Pakistan, but without weapons and is now on course to b e c o m e t h e fourth success, instead, in September 2010, China officially communicated to the IAEA that it would go ahead ^'^'^ ^^^ ^^^^ °^ chashma 3 and 4 to Pakistan—a I , 1 idigv^oL xl^^^x^^a.L strategic tit for tat to counter U.S. success in getting ^^ unconditional exemption for India in the NSG, weapons state and to provide Pakistan with an opportunity to sta- of France. bilize the Indo-Pakistan equation.^'' U.S. intelligence assessments in January 2011 concluded that Pakistan has deployed nuclear weapons numbering in the range of the mid-90s to 110, overtaking India, and is now on course to become the fourth largest nuclear weapons state ahead of France.^^ The deepening of the China-Pakistan alliance in scores of bilateral accords, pacts and MOUs for cooperation in space, defense, technology, infrastructure and trade was on full display during Premier Wen Jiabao's December 2010 visit to Pakistan. Wen characterized the relationship as going beyond bilateral cooperation to exert influence on broader regional and international issues.^' CHINA-INDIA RIVALRY IN THE INDIAN OCEAN Pakistan is a valuable partner for China in its rivalry with India for influence in the Indian Ocean region. India's geographical position provides easy access to the major oil shipping routes from the Middle East to the Pacific, close to the navigational choke points of the Strait of Hormuz into the Persian Gulf, and the 8 I JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The Breakout of China-India Strategic Rivalry in Asia and the Indian Ocean Strait of Malacca at the entrance to the South China Sea and the Pacific Ocean. China's coastal area, by contrast, offers direct access only to the seas flowing into the Pacific after passage through the Strait of Malacca, through which ships must travel to reach Hormuz by crossing the entire Indian Ocean into the Arabian Sea. It is Gwadar, in Pakistan's southwestern Baluchistan province, that provides the optimal strategic location on the Arabian Sea—virtually continuous with the Strait of Hormuz and the Persian Gulf. In 2000, the Chinese accepted Pakistan's request to fund the development of a deepwater port at Gwadar, with docking and refueling facilities for China's the largest oil tankers. China's engineering feat in constructing the highest railway in the world over the Karakoram mountains to Tibet and the construction fiirp>Qt i^r\ T A' ^^ SeriOUS of modern roads and high-speed rail links to Gwadar, COUld with plans for pipelines carrying natural gas and oil, could serve the strategic interests of both Pakistan and China, connecting the Middle East, Pakistan, China and Central Asia into a 21st century version of the silk route. China's construction of a pipeline from India's _ íntluentíal '\1[ Gwadar port would substantially reduce its dependence on the narrow Malacca Strait for oil supplies from the Middle East. Construction of a pipeline and rail lines from the historic Silk Road town of Kashgar to Gwadar can help develop a trading hub to deepen China's links with Central Asia. Robert Kaplan cautions that this is unlikely to materialize in the foreseeable future because of political turmoil across the region, including the Baluch insurgency, instability in Afghanistan and the threat to Pakistan itself from the Pakistani Taliban.''° India, meanwhile, has hedged against the long-term success of Gwadar by building an $8 billion giant naval base in the adjacent area at Karwar south of Goa on its own Arabian Sea coast, which can berth forty-two ships, including submarines, to prevent any efforts by Pakistan and China to block its entrance into the Gulf of Oman and the Strait of Hormuz. Nevertheless, China's strategic threat to India is serious and could displace India's position as the main influential power in neighboring countries. In 2007, China responded to requests from Sri Lanka for construction of the state-of-theart Hambantota port project at the juncture of the Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal. It is also constructing the deep sea port of Kyauk Phyu in the western Rakhine State of Myanmar near the Shwe gas fields, counted among the world's largest natural reserves. Myanmar has already started work on an oil pipeline and railway from Kyauk Phru to southwestern China's Yunnan province. Chinese, Japanese SPRING/SUMMER 2011 19 Erancine R. Erankel and Korean companies are also expected to invest in the multibillion dollar Dawei Development Project awarded by the Myanmar government to a Bangkok based conglomerate, and which will supply energy to Thailand."" Bangladesh has also received assurances from China of support to build a deep sea port at Sonadia and a Chittagong-Kunming Highway via Myanmar. India's presence can counter China's increasing influence in Myanmar and Thailand, as well as what some fear is the Chinese aspiration for a "bamboo curtain" in Southeast Asia."*^ India is hoping to develop the Rakhine port of Sittwe to construct Delhi's '-^*-' pipelines, one running north through Myanmar >. • 1 and Bangladesh to Kolkata, and the second tran. siting around Bangladesh on Indian territory to bring dU-VlöUlö energy to its northeast states, an area of insurgen- a realistic that India cies suspected by India's external intelligence agency °^ being supplied with weapons through contacts involving Chinese arms companies."*^ Indonesia, with cannot compete ^ ,^. ,„^„ .,,. ^ . . , .. , ten to twenty a population or 240 million, sits where the Indian and Pacific Oceans are linked by the Strait of Malacca. It is a major oil and gas producer, a potential economic giant and a secular democracy—and it is being pressured by China. In 2005, Indonesia signed a strategic partnership with Beijing and, in 2007, an agreement years. to collaborate on defense matters. China Offshore Oil Wltn venina economically •within t h e nP>rt Corporation is its largest offshore oil producer. With its very small defense budget, Indonesia is uneasy about China's rising power. Kaplan believes that there is a dislike and a "quiet fear of China" in most countries of Southeast Asia, and that "all these countries hope that a continued American naval presence combined with the use of the Indian and other navies such as Japan's and South Korea's will serve to balance against China's power."'*'' OUTFLANKING CHINA'S CHALLENGE New Delhi's national security advisors hold a realistic view that India cannot compete with China economically within the next ten to twenty years. China's sustained trend of 9 to 10 percent annual growth since 1978 was first matched by India in the period from 2005 to 2008, three consecutive years in which it experienced over 9 percent annual growth; India's economic growth trend was subsequently broken by the world financial crisis.''^ Its rebound to 8.9 percent in the first half of 2010-11 suggests growth rates close to those of China may become sustainable."** Nevertheless, the current gap between India and China is stark. China's GDP 10 I JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The Breakout of China-India Strategic Rivalry in Asia and the Indian Ocean in 2010 of over $5 trillion slightly exceeded that of Japan, maldng it the world's second largest economy and eclipsing India's GDP of $1.43 trillion.'*'' China's large industry sector of almost 47 percent of GDP has powered its export growth to become the world's second largest trading country surpassing Germany. India's industry sector is 28.6 percent of a much smaller GDP, while services, at 55 percent, constitute the dominant sector."*^ In 1991, India's Look East policy was adopted to strengthen economic, political and security interactions with Southeast Asian and East Asian countries. The policy offers the promising option to outflank China's encirclement. India enjoys equal status in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as a full dialogue partner, along with China, Japan and South Korea. ASEAN, founded in 1967 by Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand to promote economic cooperation and regional peace at a time of U.S. and Chinese enmity in Indochina and Southeast Asia, aimed at closer diplomatic and economic cooperation to prevent external intervention. The 1976 Treaty of Amity and Cooperation (TAC) in Southeast Asia committed its ratifying members to settle all disputes by peaceful means. ASEAN's core membership expanded to ten states, which retained all decisionmaking powers, but spawned a variety of forums to broaden ASEAN's reach to countries outside Southeast Asia.""' During the 1990s, ASEAN became a free trade area (FTA) with an architecture of ASEAN Plus Three Dialogue partners, China, Japan and South Korea, for better integration of these economies. China's rapid export surge and import expansion from its role in the processing form of trade—linking production networks in ASEAN countries to China-based foreign firms for final assembly of products exported to the United States and the EU—overtook ASEAN's growth trends.^° An ASEANChina FTA came into full effect on 1 January 2010, alongside ASEAN FTAs with South Korea and Japan. India became a full Dialogue Partner in 1995, which was an anomaly given its relatively low percentage of world exports (0. 95 percent) and global imports (1.2 percent) in 2005.^' Nevertheless, ASEAN was receptive to negotiating an India-ASEAN FTA with an emphasis on trade liberalization in services and investments, so far ratified by four of the ten member countries. Apart from economic integration with ASEAN, India seeks bilateral ties with countries in the region that have tense relations with China.'^ Vietnam received investments from India for the exploration and production of oil in deepwater blocks, and will provide assistance in the maintenance and repair of Indian naval ships. India and Malaysia have agreed on a Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement.^^ A Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement with South Korea came into effect in January 2010 and elevated India-Korean relations to a "strategic partnership" with an emphasis on naval cooperation.^"* A major breakthrough in SPRING/SUMMER 2011 U Francine R. Frankel October 2010 was tbe Comprehensive Economic Partnersbip Agreement between India and Japan to expand trade in goods and services and Japanese FDI into India, especially in tbe infrastructure sector.^^ Tbe free-trade agreement signed by tbe two governments on 16 February 2011 will remove tariffs on 94 percent of trade between India and Japan over ten years and make tbem each otber's biggest free trade partners.'^ A political opening to curb Cbina's influence in ASEAN surfaced after differences between Japan and Cbina emerged over tbe ASEAN decision to bold an East Asia Summit (EAS) in 2005 and over bow to plan for the goal of an East Asian Community. Cbina wanted ASEAN Plus Three to remain tbe core group reflecting its view of a China-centered Asia. According to tbe People's Daily, Japan was trying to "drag countries outside tbe region such as Australia and India into tbe community to serve as a counterbalance to Cbina... and draw in tbe United States, New Zealand and Australia to build up U.S. Japan-western dominance."^'' The conditions set by ASEAN for membership were: (1) substantive relations witb ASEAN; (2) full status as a dialogue partner; and (3) accession to TAC. ASEAN alone retained the authority to decide future members of subsequent summits "to ensure tbat ASEAN remains in the driver's seat of tbe EAS process."^^ India bad signed TAC on 8 October 2003, followed by Australia and New Zealand, who signed tbe Treaty before tbe first EAS meeting on 14 December 2005. Japan and India continued to press tbeir view tbat tbe EAS sbould be tbe focus of tbe longterm goal to build an East Asian Community. Tbey appeared to bave prevailed at tbe fifth meeting of tbe East Asian Summit in Hanoi on 30 October 2010, wben tbe United States and Russia attended and were invited to join as members at tbe sixtb EAS meeting. U.S. secretary of state Hillary Clinton had signed tbe Instrument of Accession to the TAC Treaty on 22 July 2009, on the ground that "tbe United States must bave strong relationships and a strong and productive presence here in Soutbeast Asia."'^ India bad moved into the inner group of Asian countries eager to balance Cbina's power. "No INTERFERENCE W I L L BE TOLERATED" An unexpected series of aggressive maritime moves by Cbina, cballenging disputed claims over islands in tbe South Cbina Sea and adjacent waters, bas pusbed the Obama Administration to shift its emphasis from the engagement to the balancing side of U.S.-Cbina relations. Tbis sbift was accompanied by moves to reinforce alliances witb Soutb Korea and Japan and bring tbe disputed Senkaku Islands under tbe protection of tbe U.S.-Japan alliance.^" Tbe United States was forced to focus on tbe scope of Cbina's ambitions once Beijing suspended all military talks in early 2010 to protest President Obama's 12 I JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The Breakout of China-India Strategic Rivalry in Asia and the Indian Ocean tneeting with the Dalai Lama and Washington's arms sale to Taiwan of $6.7 billion. A few months later, China asserted its right to regulate foreign military activities in its 200-nautical mile maritime Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), and pressed its claim to most of the South China Sea as a "core national interest." Visiting U.S. officials were informed that no interference within this vast area of 1.2 million square miles would be tolerated. The warning was so stark because a third of global maritime commerce and more than half of Northeast Asia's oil supplies pass through these waters and U.S. naval forces routinely travel the seas between the Pacific and Indian Oceans. China also opposed the conduct of military exercises between China's the United States and South Korea in the Yellow Sea j • , • J u T^ r, , ,*n , between Chtna and the Korean Península. When the exercises were held in September 2010, the Chinese charged the United States with "tight encirclement of China."*' China's new strategy of "far sea defense," its submarine base on Hainan in the South China Sea, modernization ^^ Q i r e C t e Û a t displacing U. S. inflllPTirP i n i -r» • rt h p I il PI FT r* cn^ixn^ aSSerting S t a t U S aS a and claims to exclusive rights in international waters challenging U.S. Navy supremacy led to redeployment of U.S. naval forces from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The rapid buildup of China's warships, submarines and the development of the game-changing anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs) to act as an "anti-access" force against U.S. intervention in a conflict involving Taiwan, persuaded the Pentagon that China's military modernization was directed at displacing U.S. influence in the Pacific and asserting China's status as a major world power. The U.S. message to China, conveyed by Secretary Clinton during a speech at Hanoi to the ASEAN Regional Forum on 23 July 2010, was direct: the "United States like every nation, has a national interest in freedom of navigation, open access to Asia's maritime commons, and respect for international law in the South China Sea."''^ The American chief of staff Admiral Mike Mullen flew to Delhi in July 2010 for talks about ensuring stability in the vital Pacific and Indian Ocean regions. President Obama's three-day visit to India in November 2010 was part of a big push for enhancing U.S.-India strategic cooperation at the center of the nuclear deal. The President's address to a Joint Session of the Indian parliament on 8 November 2010 drew an implicit equivalence between India and China, asserting India is not an "emerging" power, but one that has already emerged. President Obama went on to state, "my firm belief that the relationship between the United States and India—bound by our shared interests and our shared values—will be SPRING/SUMMER 2011 I 13 Erancine R. Erankel one of the defining partnerships of the 21st century." He assured India that the United States looks ahead to a reformed UN Security Council that includes India as a permanent member, and announced his administration would remove the Indian Space and Research Organization (ISRO) and the Defense Research and Development Organization (DRDO) from the "Entities List" in order to open up trade in dual-use and strategically sensitive materials. The United States will also work with India to accomplish New Delhi's full membership in the four multilateral export control regimes, including the NSG.^^ CONCLUSION Overlapping claims for influence in South and Southeast Asia and within the Indian Ocean, long understated by both China and India, have surfaced in a far-ranging strategic rivalry. China's asymmetrical economic strength and military power will put great pressure on India's resources to meet the challenge. Nevertheless, precisely for the reason that India is the weaker and less threatening of the two Asian powers, it has been welcomed as a partner by smaller countries apprehensive about China's rapid rise. Aggressive territorial claims by China in the Pacific that challetige the security interests of Japan and the United States have provoked powerful support for a balancing strategy that includes India. What started as a strategic rivalry between China and India in the Indian Ocean, and then expanded to China and the United States in the Asia-Pacific, suggests a pan-Asia challenge by China with consequences that are difficult to predict. Discussions between President Obama and President Hu during his state visit to the United States in January 2011 aimed at stabilizing the relationship as one of cooperation, but also of "friendly competition." Premier Wen had used similar language in New Delhi to describe China-India relations as partners, not rivals. Yet, the rhetoric runs up against inconvenient realities that have arisen from a reassessment of China's intentions. A coalition of democracies—the United States, India, South Korea and Japan—is solidifying to balance the expansive ambitions of China in Asia. The hedging policies of India, or for that matter those of the United States, focus on possible arenas of conflict; namely, India's military commitment to meet contingencies of sharp, short border wars and two-front wars alongside the Pentagon's plan to step up investment in a range of weapons and technologies in response to the Chinese military buildup in the Pacific.^'' '^ NOTES ' Susan L. Shirk, "One-Sided Rivalry: China's Perceptions and Policies Toward India" in The IndiaChina Relationship, What the United States Need to Know, ed. Francine R. Frankel, Harry Harding (New 14 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The Breakout of China-India Strategic Rivalry in Asia and the Indian Ocean York: Columbia University Press and Wasbington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2004). ^ S. Prasannararajan and Sandeep Unnitban, "Tbe Two Faces of Obama," India Today International 4 November 2010, 13. •^ "India Loses 'Substantial Land' in 20-25 years alone LAC to Cbina," Econotnic Times, It lanuarv 2010. "* Autbor's interview and worksbop meetings in Beijing, July 2001. ^ Jasjit Singb, "Security Concerns and Cbina's Military Capabilities: Tbe Eagle, tbe Dragon and tbe Elepbant" in Power Alignments in Asia, China, India and the United States, ed. Alyssa Ayres, C. Raja Moban (New Delbi: SAGE Publications India Pvt. Ltd., 2009), 125. * "Pak Handing over De-facto Control of Gilgit Region to Cbina," Zee News, 28 August 2010, bttp:// w\vvv.zeenews.com/news65I367.btml. ^ "Wide Presence of Cbinese cos in POK Worries India," Economic Times, 29 October 2010. ^ "Govt Says Arunacbal Integral Part of India after Cbinese Protest," Times of India, 13 October 2009, bttp://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Govt-says-Arunacbal-integral-part-of-India-afterCbinese-protest/articlesbow/5118757.cms. ^ Saransb Sebgal, "Mandarin education plan riles Tibetans," Asia Times, 4 November 2010, bttp:// www.atimes.com/atimes/Cbina/LK04Ad02.btml. '° Robert D. Kaplan, "Tbe Geograpby of Cbinese Power: How Far will Beijing Reacb on Land and at Sea?" Foreign Affairs 89, 3 (Spring 2010), 26. ' ' "Indian Hegemony Continues to Harm Relations witb Neigbbors," People's Daily, 14 October 2009, bttp://englisb.peopledaily.com.cn/90001/90780/91343/6783357.btml. '^ M. K. Bbadrakumar, "Tbe Dragon Spews Fire at tbe Elepbant," Asia Times, 17 October 2009, bttp://www.atimes.com/atimes/Soutb Asia/KJ17DfO2.btml. '^ "Being Assertive witb Cbina - Witbout Fuss," Daily News and Analysis, 26 October 2010, bttp:// www.dnaindia.com/opinion/editorial being-assertive-witb-cbina-witbout-fuss_ 1457918. '"* Siddbartb Varadarajan, "India Tells Cbina: Kasbmir is to Us Wbat Tibet, Taiwan are to You," Tlte Hindu, 15 November 2010, bttp://www.tbebindu.com/news/national/article886483.ece. '^ "Wen Backs Greater International Role for India," The Hindu, 16 December 2010. '* Suman Sbarma, "Cbina's War Plan," Open Magazine, 10 April 2010. ''' Sandeep Unnitban, "Tbe Cbipak Tbreat," India Today International, 1 November 2010, 2t. '^ Lydia Polgreen, "India Digs Under tbe Top of tbe World to Matcb a Rival," Nei<i York Times, 1 August 2010. " Kaveree Bamzai and Sandeep Unnitban, "Hidden Dragon Croucbing Lama," India Today International, 14 February 2011, 13. 20 Unnitban (2010), 20-24. ^' Kaveree Bamzai and Sandeep Unnitban (2011). 2^ For an analysis of tbe cballenges faced by tbe Indian army in developing tbe capabilities to figbt sbort and sbarp conflicts on two fronts, see Colonel Harinder Singb, "India's Emerging Land Warfare Doctrines and Capabilities" (RSIS Working Paper No. 210, Singapore, 13 October 2010). ^^ Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis, IDSA Comment, Laxman K. Bebara, "Budgeting for India's Defence: An Analysis of Defence Budget 2010-11 and tbe Likely Impact of the 13tb Finance Commission on Future Defence Spending," 3 Marcb 2010. ^'' Stockholm International Peace Researcb Institute, SIPRI Yearbook 2010: Armaments, Disarmament and International Security (Stockbolm: Stockbolm International Peace Researcb Institute, 2010). ^^ "Army to be Letbal, Agile Force witb Two-Front War Capability," Tiiaindian News, 14 January 2011, bttp://wvvw.tbaindian.com/newsportal/uncategorized/army-to-be-letbal-agile-force-vvitb-twofront-war-capability_100488015.btml. '^'^ Gurmeet Kanwal, "Wbere is tbe Strategy?" Indian Express, 27 November 2010, bttp://vvww.indi- SPRING/SUMMER2011 I 15 Francine R. Frankel anexpress.com/newsAVhere-is-the-Strategy/716649. ^'' M. Shanisur Rabb Khan, "The Strategie Significance of Arihant," Institute of Peace & Conflict Studies, 31 August 2009, http://www.ipcs.org/article/navy/the-strategic-significance-of-arihant-2960. html. ^^ Ronald O'Rourke, "China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy CapabilitiesBackground and Issues for Congress," 26 August 2010 (Congressional Research Service 7-5700 RL33I53), 19. ^^ C. Raja Mohan, "India and the Changing Geopolitics of the Indian Ocean" (Eminent Persons Lecture Series, National Maritime Foundation, New Delhi, 19 July 2010). •^^ Robert D. Kaplan, Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power (New York: Random House, 2010), 127. 3' O'Rourke, 17-18,21-24. ^^ Indian Navy, "Currently Active Fleet Strength and Details," Bharat Rakshak, 20 January 2009, http://www.bharat-rakshak.com/NAVY/Ships/Active/198-Fleet=Strength.html. ^^ Ahmed Rashid, Descent into Chaos: The United States and the Failure of Nation Building in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Central Asia (New York: Viking, 2008), 287. ^'* Francine R. Frankel and Harry Harding, ed., Tlte India China Relationship: Wlmt the United States Needs to Know, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 200. ^^ "Khusab Plutonium Plant Can Produce 50 Bombs per Year," Times of Kabul, 6 October 2010, http://www.timesofkabul.com/?p=290. ^^ Glenn Kessler, "Questionable China-Pakistan Deal Draws Little Comment from U.S.," Washington Post, 20 May 2010, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/05/19/ AR2010051905471.html. 3'' Tanvi Kulkarni, "Sino-Pak Nuclear Engagement-1: The Big 'Deal'" (IPCS China-Articles #3303, Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, 29 December 2010), http://www.ipcs.org/article/Pakistan/sinopak-nuclear-engagement-i-thebig-deal-3303%20html. ^^ David E. Sänger and Eric Schmitt, "Pakistani Nuclear Arms Pose Challenge to U.S. Policy," Neyv York Times, 31 January 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/201 l/02/01/world/asia/olpolicy.html?_r=2&.hp. -*' K. Alan Kronstadt, "Pakistan-U.S. Relations" (Congressional Research Service Report for Congress 7-5700, Washington, DC, 6 February 2009), http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL33498.pdf. '*'' Kaplan, 128. Much of the following discussion about China-India rivalry in the Indian Ocean draws on Kaplan's work. "*' International Herald Tribune, "Unblemished Coastline in Myanmar Awaits a Shower of Development," New York Times, 28 November 2010, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9 801E3D6I23CF93BA15752C1A9669D8B63. '*2 Kaplan, 219. '*^ Saikat Datta, "The Great Claw of China," Outlook, 7 February 2011, http://wwvv.outlookindia. com/article.aspx?270223. "*'* Kaplan, 273. "•5 Interim Budget 2009-2010, Pranab Mukherjee Speech, 16 February 2009, http://www.hindu. com/nic/interimbud09.htm. ''^ Ashok Dasgupta, "Mid-Year Analysis Projects 9% Growth," The Hindu, 8 December 2010, http:// www.hindu.com/2010/12/08/stories/2010120862952000.htm. "*' "China Overtakes Japan as World's Second-Biggest Economy," Bloomberg News, 16 August 2010, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2010-08-I6/china-economy-passes-japan-s-in-second-quarter. '*^ India Economy 2011, 2011 CIA World Factbook and Other Sources, http://vvww.theodora.com/ wfbcurrent/india/india_economy html. "*' Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam subsequently joined. ^^ Nicholas R. Lardy, "The Economic Architecture of China in Southeast and Central Asia" in Power 16 I JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The Breakout of China-India Strategic Rivalry in Asia and the Indian Ocean Realignments in Asia: China, India and the United States, ed. Alyssa Ayres, C. Raja Mohan (Location: SAGE, 2010), 25-33. ^' ASEAN Secretariat, "Merchandise Imports and Trade Balances of ASEAN, China and India" (Studies Unit Brief, Studies Unit Paper No. 11-2006, December 2006), 3. ^^ "India for ASEAN Alliance to Counter 'Aggressive' China," Hindustan Times, 14 October 2010, http://www.hindustantimes.com/StoryPage/Print/612589.aspx. ^^ Panchali Saikia, "Manmohan Singh in Southeast Asia," Institute of Peace &. Conflict Studies, 27 October 2010, http://www.ipcs.org/article/southeast-asia/manmohan-singh-in-southeast-asia-3267. html. ^'' Harsh V. Pant, "Rise of China Prods India-Korea ties," Japan Timts, 7 September 2010, http:// search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/eo20100907aLhtml. ^^ Press Information Bureau, Government of India, Prime Minister's Office, 25 October 2010. ^^ Andrew Monahan, "Japan, India Sign Free-Trade Pact," Wall Street Journal, 16 February, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10000142405274870440999004576145942204415406.html. ^^ "East Asia Summit: In the Shadow of Sharp Divisions," People's Daily Online, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/200512/07/eng20051207_226350.html (emphasis in the original). ^^ "Foreign Ministers from ASEAN, Japan, China, S. Korea Begin Talks," Peoples' Daily Online, 7 May 2005, http://english.people.com.cn//200505/07/eng20050507_183847.html. ^^ "United States Accedes to the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia," U.S. Department of State, 22 July 2009, http://www.state.gOv/r/pa/prs/ps/2009/july/126294.htm. ^'^ Jacque de Lisle, Foreign Policy Research Institute Conference (distributed via email to author, 8 January 2011), 12. *' "China Shows Sterner Mien to U.S. Forces," New York Times, 12 October 2010. ^2 Hillary Rodham Clinton, "Remarks at Press Availability" (Hanoi, Vietnam, 23 July 2010), 2, http://www.state.gov/secretary/rm/2010/07/145095.htm. ^^ Jeff F. Smith, "The U.S. is Walking the Walk," The Hindu, http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/ op-ed/article890250.ece. ^'' Elisabeth Bumiller, "U.S. Will Counter Chinese Arms Buildup," New York Times, 9 January 2011. SPRING/SUMMER 2011 I 17 Copyright of Journal of International Affairs is the property of Journal of International Affairs and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.