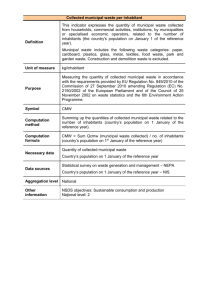

Municipal Energy Planning – Scope and Method Development

advertisement