The Loss of Chance in Civil Law Countries: A

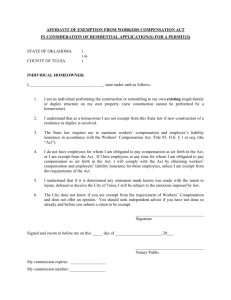

advertisement

THE LOSS OF CHANCE IN CIVIL LAW COUNTRIES: A COMPARATIVE AND CRITICAL ANALYSIS Rui Cardona Ferreira*1 ABSTRACT Bearing in mind the judgments recently given by the Portuguese Supreme Court, which have recognized the right to be compensated for loss of chance for the first time, this article sets out to discover the actual legal framework for this type of damage. In order to do so, the evolution of loss of chance within French and Italian law – the two mainland systems in which this damage has been generally accepted – will be analysed. This will be followed by a critical evaluation of the results accomplished. Dissatisfied with the traditional framework of loss of chance, alternative proposals will be sought, especially those formulated by some German scholars, given the proximity of Portuguese civil law to German civil law. The consequence is, on the one hand, the need to take into consideration the normative framing and the nature of the final damage for which the compensation for loss of chance is a substitute and, on the other hand, the need to include loss of chance, when qualified as an economic loss, in a system of civil liability with limited mobility and permeability as to value judgements. Keywords: loss of chance; civil liability; causation; autonomous damage §1. INTRODUCTION Despite the theme not being extensively addressed by Portuguese scholars, and the mainstream orientation being towards the inadmissibility of compensation for loss of chance as an autonomous damage, in 2010 the Portuguese Supreme Court of Justice * 56 PhD candidate, Law Faculty of Lisbon New University. Senior Associate at Sérvulo & Associados law firm, Lisbon. I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editorial staff of the Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law for their useful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. 20 MJ 1 (2013) The Loss of Chance in Civil Law Countries: A Comparative and Critical Analysis delivered two judgments in which the claimants were granted damages based on this theory. The judgment issued on 28 September 2010 (Proceedings 171/02), in a case of civil liability in the exercise of the legal profession, granted the plaintiff the right to compensation as a result of failure to timely submit the defence, without the court having assessed the probable degree of success in the stance to be upheld in the relevant proceedings by the plaintiff.1 In a judgment of 16 December 2010 (Proceedings 4948/07) the plaintiff was granted compensation for loss of professional earnings as a result of a road traffic accident, although the plaintiff was not performing any regular professional activity at the time of the accident. With regard to civil liability due to medical malpractice, however, a field in which the loss of chance theory has been accepted in other European laws, the Supreme Court of Justice has unvaryingly refused the patients’ right to be compensated for loss of chance.2 Although originally similar to French Napoleonic law, Portuguese civil law became structurally akin to German private law through the 1966 Civil Code, a notable example being the institution of a civil liability system aligned with the German Civil Code prior to the 2002 reform. Consequently, a useful contribution for the Portuguese debate on the theme of loss of chance and the respective legal framework must take into consideration the existing data in other mainland laws – in particular, French and Italian law, in which the loss of chance theory has been more developed –, but the critical analysis carried out by some German scholars must not be neglected. This article constitutes a summary of such legal research and aims to identify, to the extent possible, a framework for loss of chance that does not rely upon specific normative terms of French and Italian civil liability systems and may therefore be acceptable under Portuguese law and other continental laws based on the German Civil Code. 1 2 Less than a month later, however, through the judgment given on 26 October 2010 (Proceedings 1417/04), and in line with previous case law, the Supreme Court of Justice decided on the exceptional nature of compensation for loss of chance, and rejected the claim for damages based on another civil liability case in exercising the legal profession. More recently, however, through the judgments of 10 October 2011 (Proceedings 9195/03) and 5 February 2013 (Proceedings 488/09), the Supreme Court of Justice again decided in favour of the plaintiff, accepting the right to compensation for a loss of chance in two cases of professional liability. See the judgments of 15 October 2010 (Proceedings 08B1800) – with two dissenting Opinions – and 22 October 2010 (Proceedings 409/09). 20 MJ 1 (2013) 57 Rui Cardona Ferreira §2. A THE LOSS OF CHANCE IN ITALIAN AND FRENCH LAW FRENCH LAW 1. In general The origin of the loss of chance theory dates back to the Cour de Cassation ruling of 17 July 1889, in which compensation was granted for the loss of chance in pursuing legal proceedings and, therefore, winning the relevant case.3 Since this ruling, the same higher court has regularly reaffirmed the respective doctrine and recognized the right to compensation for loss of chance, particularly in lawyers and legal advisers’ professional liability cases. In essence, the idea is that the fault committed by the attorney that results in the loss of chance to preserve or satisfy the rights of the client is, in itself, a recoverable damage. However, the same notion slowly spread to other areas, with French case law recognizing that compensation for loss of chance may be due in contexts as diverse as gambling or sports competitions, progression in a professional career, development of scientific or commercial activity, or access to certain professions.4 Thus it is clear that French case law accepts the application of the loss of chance theory in quite a broad manner. As indicated by Geneviève Viney and Patrice Jourdan, such a theory has found, in France, a fertile ground both in the area of tortious liability and contractual liability, based on the loss of the possibility of obtaining a favourable event or advantage.5 Yves Chartier also mentions that, in fact, ‘there are no limits of principle nor area reserved’ to the application of the loss of chance.6 Despite the broad projection of the concept of loss of chance in French case law, and in order for the respective compensation to be recognized, certain requirements have to be met. Indeed, besides the confirmation of the civil liability general requirements, including 3 4 5 6 58 See G. Viney and P. Jourdain, Traité de Droit Civil (3rd edition, LGDJ, Paris 2006), p. 91; and Y. Chartier, La Réparation du Préjudice dans la Responsabilité Civile (Dalloz, Paris 1983), p. 33. On the profi le and various areas of application of the loss of chance, see H. Mazeaud, L. Mazeaud and A. Tunc, Traité Théorique et Pratique de la Responsabilité Civile Délictuelle et Contractuelle – Volume I (6th edition, Montchrestien, Paris 1965), p. 272 et seq.; B. Starck, Droit Civil – Obligations (Litec, Paris 1972), p. 51–53; F. Chabas, Responsabilité Civile et Responsabilité Pénale (Montchrestien, Paris 1975), p. 29 et seq.; Y. Chartier, La Réparation du Préjudice dans la Responsabilité Civile, p. 32–49; J. Carbonnier, Droit Civil – 4 – Les Obligations (18th edition, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 1994), p. 334 and p. 342 et seq.; J. Flour and J. Aubert, Les Obligations – 2 – Le Fait Juridique (8th edition, Dalloz-Sirey, Paris 1999), p. 125–127; A. Weill and F. Terré, Droit Civil – Les Obligations (10th edition, Dalloz, Paris 2009), p. 678 et seq.; P. le Tourneau and L. Cadiet, Droit de la Responsabilité (Dalloz, Paris 1998), p. 214; and G. Viney and P. Jourdain, Traité de Droit Civil, p. 91–96. G. Viney and P. Jourdan, Traité de Droit Civil, p. 96. As the authors point out, the easiness with which French case law has resorted to the loss of chance theory entailed, in fact, a perverse or abusive effect: there are cases where a partial compensation is awarded when in fact a full compensation should have been awarded. In Y. Chartier, La Réparation du Préjudice dans la Responsabilité Civile, p. 50. 20 MJ 1 (2013) The Loss of Chance in Civil Law Countries: A Comparative and Critical Analysis the existence of damage and a causal connection between the tortious conduct and the damage, it is also necessary that the chance to be compensated is deemed as real and serious. Therefore, to compensate loss of chance, it is not sufficient just to prove the previous existence of some sort of opportunity or possibility of obtaining a favourable outcome by the plaintiff: considering the specific circumstances, it is also necessary to prove that this possibility or opportunity was destroyed as a result of a harmful conduct. Moreover, the chance must have a reasonable likelihood of materialization, rather than a mere hypothetical character. Otherwise, according to French case law and scholars, the loss of chance will not meet the requirement of certainty upon which the compensation for the damage depends.7 Thus the need to confirm if the chance was real and serious is nothing more than ‘(…) a way to express that the event that became impossible was likely’, as pointed out by Chartier.8 In other words, the certainty of the damage to be compensated is replaced by the mere probability of materialization of the result that the chance offered. However, this interpretation is not entirely uniform. The issue has been particularly debated with regard to the professional civil liability of lawyers and legal advisers, which, as previously mentioned, is historically linked to the concept of loss of chance. Although the main trend in case law demands evidence of a reasonable probability of success in the action lost (or not initiated), another line of thought in case law has granted compensation to the plaintiff regardless of the particular circumstances of the previous legal action, arguing that no legal action is lost beforehand and that the simple fact that legal proceedings have begun is of importance in applying pressure on the relevant counterparty.9 With respect to this second rationale, the low probability of obtaining a favourable judicial decision in the primitive action does not prevent the award of compensation to the injured client: it only affects the respective amount of compensation. This is also the preferred view of Viney and Jourdan, sustaining that compensation shall be granted whenever the dismissal of the underlying action was not certain, and that, in such circumstances, the payment of compensation would be at least ‘(…) a private sanction that may be useful’.10 As for the amount of compensation, it is usually stated that the loss of chance only entitles the plaintiff to partial compensation. This aims to highlight that the compensation is equivalent to a fraction of the value or advantage that was denied as a result of the loss of chance.11 7 8 9 10 11 G. Viney and P. Jourdan, Traité de Droit Civil, p. 99. In Y. Chartier, La Réparation du Préjudice dans la Responsabilité Civile, p. 50. G. Viney and P. Jourdan, Traité de Droit Civil, p. 99–100. Ibid., p. 100. As F. Chabas mentions, ‘the loss of chance itself, as long as it is not a hypothetical damage, is a reparable damage, but, by force of alea, it entitles to compensation for damage in an amount inferior to what would be due for the loss of an already acquired right’ – in F. Chabas, Responsabilité Civile et Responsabilité Pénale, p. 30. 20 MJ 1 (2013) 59 Rui Cardona Ferreira Nevertheless, French scholars allege that one is not facing any exception to the principle of full redress, but that the reduction at hand expresses the loss of chance as a specific and autonomous damage having as reference the final damage.12 The fact, however, is that when it comes to determining the effective amount of compensation, the same scholars also recognize that the reference should be the value of the final damage and that the amount should reflect the fraction equivalent to the probability of materialization of the lost chance.13 Thus, even under the understanding that the probability or seriousness of the chance does not constitute a requirement of the right to compensation, the triggering of civil liability for the loss of chance always requires, firstly, proof of the materialization of the final damage itself and, subsequently, the judge’s assessment of the case elements regarding that very same degree of probability (at least to determine the amount to be awarded).14 2. In medical malpractice Stretching back to the 1960s, the concept debated here has been particularly developed in French case law, in terms of the loss of chance of recovery or survival in civil liability for medical malpractice.15 Resorting to the loss of chance as an instrument consciously applied in overcoming the difficulties created in such an area, by the demands of proof of a causal connection, emerged from a decision of the Cour d’appel of Grenoble on 24 October 1961, in a case concerning the lack of a timely diagnosis of a fracture already confirmed by a radiography, with subsequent deterioration of the patient’s health.16 A few years later, it was the Cour de Cassation itself that confirmed this doctrine through a judgment dated 14 December 1965, followed by several decisions in similar cases of medical malpractice.17 There are situations in which, following mistakes in the diagnosis or malpractice in the treatment, the patient died or his or her health deteriorated; in other words, if it were not for the mistake, the death or the deterioration of the patient condition could have been prevented. Situations of breach of duty in informing the patient of the risks of the treatment to be adopted or with respect to a determined surgical procedure have been considered, to a certain extent, as equivalent to situations of misdiagnosis or fault in medical treatment. An expedition through French scholars in this last area of civil liability allows for the identification of four different positions, namely: 12 13 14 15 16 17 60 G. Viney and P. Jourdan, Traité de Droit Civil, p. 102. Ibid., p. 103. Y. Chartier, La Réparation du Préjudice dans la Responsabilité Civile, p. 51–52. Ibid., p. 35 et seq. G. Viney and P. Jourdan, Traité de Droit Civil, p. 229. Ibid., p. 230 and note 185. 20 MJ 1 (2013) The Loss of Chance in Civil Law Countries: A Comparative and Critical Analysis a) A more conservative or traditional position, according to which there would be a spurious application of the loss of chance theory in the group of cases at hand, where it would be impossible to identify an autonomous damage (that is, a damage other than the final harm to the relevant patient’s health or life);18 b) A second position, according to which there are no substantial differences between this field of the loss of chance and any other, but alleging that the application of this theory in medical malpractice results in a decrease in the (full) compensation that should be awarded to the plaintiff based on the unlawfully created or increased risk;19 c) A third position that supports an univocal perspective of the loss of chance and its undifferentiated application to the most varied areas, including medical malpractice;20 d) Finally, the perspective that the loss of chance does not present any special branch within the context of civil liability for medical malpractice, but rather constitutes, in all its manifestations, an expression of an idea of partial causation and not a truly autonomous damage.21 This diversity of insights – which constitutes a fracture in the merely apparent consensus regarding the loss of chance in French law – clearly reveals the complexity and uncertainties that surround this subject. 3. The civil liability system context In France, the issue of the loss of chance is concerned with the requirement regarding the certainty of the damage. As mentioned by Chartier, the idea of certainty of the damage is based upon common sense, as otherwise one could be enriching the plaintiff without reason.22 Therefore, the mere possible or hypothetical damage may not be recovered. Accordingly, loss of chance ensures the plaintiff some compensation when the final damage confirmation is random, but it is still possible to verify a serious probability of the respective occurrence. Indeed, due to such randomness, the final damage may not be considered certain, and even a partial compensation pertaining to that damage would be in conflict with another civil liability principle: the principle of full redress.23 18 19 20 21 22 23 See R. Savatier, La Théorie des Obligations en Droit Privé Économique (4th edition, Dalloz, Paris 1979), p. 304; J. Penneau, La Responsabilité du Médecin (Dalloz, Paris 1992), p. 31; and J. Carbonnier, Droit Civil– 4 – Les Obligations, p. 343. See G. Viney and P. Jourdan, Traité de Droit Civil, p. 231–233 and p. 236. See Y. Chartier, La Réparation du Préjudice dans la Responsabilité Civile, p. 38–39. See J. Boré, ‘L’indemnisation pour les chances perdues: une forme d’appréciation quantitative de la causalité d’un fait dommageable’, 38 JCP 1 (1974), p. 2620; and, more recently, F. Descorps-Declère, ‘La cohérence de la jurisprudence de la Cour de cassation sur la perte de chance consécutive à une faute du médecin’, 11 Recueil Dalloz (2005), p. 742–748. Y. Chartier, La Réparation du Préjudice dans la Responsabilité Civile, p. 21. Mentioning this principle, see G. Viney and P. Jourdan, Traité de Droit Civil, p. 82; J. Carbonnier, Droit Civil – 4 – Les Obligations, p. 447–448; P. Conte and P. Maistre du Chambon, La Responsabilité Civile délictuelle (Presses universitaires de Grenoble, Grenoble 2000), p. 23–25. 20 MJ 1 (2013) 61 Rui Cardona Ferreira However, the certainty of the loss of chance appears as a relative certainty or a second degree certainty,24 since, by nature, it is impossible to know if the advantage pursued would have been attained or the loss avoided, if the chance had not been lost or destroyed.25 In fact, the autonomy of the loss of chance regarding the final damage is not unquestionable: such autonomy needs to be questioned from the moment one confirms that the possibility of compensation for the loss of chance, from a double perspective, rests upon the probable confirmation of the final damage. As stated by Chartier, ‘(…) it is the very degree of probability of the invoked chance lost that, in the same manner, justifies redress and determines the fraction of the expected yield, or of the loss unable to prevent, that is to be compensated’.26 The so-called autonomy of the loss of chance only appears in an obvious manner, and in a coherent fashion, in cases where one may argue that the possibility of compensation and the amount to be awarded are relatively indifferent to the degree of probability of the materialization of the chance.27 Within that framework, the only requirement is the existence of some (or any) chance and, therefore, the respective loss justifies the granting of compensation to the plaintiff, as long as the general requirements of civil liability are met. From the perspective of positive law, the appearance and expansion of the loss of chance, as an autonomous economic loss, may not be separated from the fact that the French Civil Code established an open clause in terms of tortious liability, which is based upon the notion of faute (Article 1382 of the French Civil Code). Consequently, the theory of lost chance may be difficult to export, at least to the extent in which it is recognized in France, to civil liability systems that tend to limit tortious civil liability to the breach of absolute rights or legal provisions designed to protect third parties, such as the German and Portuguese systems. From this perspective the French civil liability system is also defined, in terms of causation, by Article 1151 of the French Civil Code, which adopts a formula of imprecise meaning. In effect, Article 1151 does not seem to have precise contents and tends to be interpreted, essentially, in a negative sense, having as its aim the repudiation of the consequences resulting from the linear and blind application of the conditio sine qua non (but-for test)28 theory. 24 25 26 27 28 62 See Y. Chartier, La Réparation du Préjudice dans la Responsabilité Civile, p. 22. P. Conte and P. Maistre du Chambon also mention that ‘(…) the loss of chance presents itself as an actual damage, in the sense that the expected yield is defi nitely lost. But it is also an uncertain damage, because nothing ensures that the plaintiff, in case the events had unfolded under normal circumstances, would have obtained the frustrated yield’ – in P. Conte and P. Maistre du Chambon, La Responsabilité Civile délictuelle, p. 41. In Y. Chartier, La Réparation du Préjudice dans la Responsabilité Civile, p. 32. Highlighting the same aspect, see A. Weill and F. Terré, Droit Civil – Les Obligations, p. 680. As mentioned before, this case law trend is not uniform, but receives the approval of G. Viney and P. Jourdan. See R. Savatier, Traité de la Responsabilité Civile en Droit Français (Volume II, Barnéoud Frères, Paris 1939), p. 95–96; G. Viney and P. Jourdan, Traité de Droit Civil, p. 192; J. Carbonnier, Droit Civil– 4 – Les 20 MJ 1 (2013) The Loss of Chance in Civil Law Countries: A Comparative and Critical Analysis In summary, one may conclude that the configuration of the loss of chance, as an autonomous damage, fi nds a particularly fertile domain in the French civil liability system, both in terms of the amplitude of the notion of faute and in the reduced aptitude for the prospection of alternative constructions that situate the loss of chance in terms of causation. However, even in France, the precise contours of the loss of chance are subject to controversy, especially in the area of civil liability for medical malpractice. B. ITALIAN LAW 1. In general It is worthwhile to begin by mentioning that in Italy, as in France, there is a school of thought that qualifies loss of chance as an autonomous damage.29 A different line of orientation, however, considers the loss of chance solely as a criterion of causation concerning loss of profits or, from a broader perspective, a damage that is not proved according to the parameters that are normally adopted in matters of causation.30 The concept of loss of chance as loss of profits was also considered with some reservation in the Italian legal system. This was due to the difficulty in proving a causal connection between the wrongful conduct and the lost chance. Even though some judgments accept this classification, and even grant the plaintiff compensation, loss of chance has been more easily classified as an autonomous damage, corresponding to the offence of a legal situation that has already been achieved by the plaintiff and it is described as the possibility of acquiring the advantage that chance refers to. Two judgments from the Corte di Cassazione labour court are usually highlighted as cornerstones for the latter’s orientation. These two trials dealt with procedures that were illegally interrupted concerning the hiring and promotion of employees (refer to 29 30 Obligations, p. 334–335. Also in the sense that the demand of an immediate and direct relation only requires a sufficient causal connection, see A. Weill and F. Terré, Droit Civil – Les Obligations, p. 681. See A. De Cupis, ‘Il risarcimento della perdita di una chance’, in 1 Giur. It 1 (1986), p. 1181; F. Ghisiglieri, ‘Risarcimento del danno e perdita di chance’, NGGC (March/April 1991), p. 141–142 and p. 145; M. Franzoni, Il Danno al Patrimonio (Giuff rè, Milan 1996), p. 228–229; P.G. Monateri, ‘Le Fonti delle Obbligazioni, 3 – La Responsabilità Civile’, in F. Galgano, Trattato di Diritto Civile (Wolters Kluwer Italia Srl, Turin 1998), p. 283–285; N. Monticelli, ‘La perdita di chance’, in G. Alpa et al. (ed.), NGCC – Casi Scelti in Tema di Responsabilità Civile (CEDAM, Padua 2004), p. 178. See C. Castronovo, La Nuova Responsabilità Civile (3rd edition, Giuff rè, Milan 2006), p. 545, note 212 and p. 761–763. Supporting loss of chance as loss of profit within the domain of pre-contractual liability, in opposition to what is accepted by the author within the remaining domains of civil liability, see A. Sagna, Il Risarcimento del Danno nella Responsabilità Precontrattuale (Giuff rè, Milan 2004), p. 138 et seq. Never taking a stand on the defi nition of loss of chance, but taking note of the terms of controversy and hesitations among court decisions, see A. Baldassari, Il Danno Patrimoniale (CEDAM, Milan 2001), p. 177–199; and T. Gualano, ‘Perdita di chance’, in G. Vettori (ed.), Il Danno Risarcibile (Volume I, CEDAM, Padua 2004), p. 121–190. 20 MJ 1 (2013) 63 Rui Cardona Ferreira judgment of 19 November 1983, No. 6906)31 or where a certain employee was illegally prevented from carrying out admission tests necessary to secure a particular position (refer to judgment of 19 December 1985, No. 6506).32 In the former case, the Corte di Cassazione ruled that the compensation refers ‘(…) not to the loss of a favourable result but rather the loss of the possibility to achieve a profitable result, a possibility that existed when the company’s illicit behaviour affected [the employee’s] right’. In the other case, the Corte di Cassazione reinforced this understanding and clarified that the burden of proof for the existence of the chance, as a damage that can be compensated for, is incumbent on the plaintiff under the general terms. It also clarified that those who present a 50% higher probability in achieving the result that the chance refers to satisfy the same burden. In the latter judgment, the Corte di Cassazione also presented an explicit directive to guide the determination of the amount of compensation: the value attributed to the chance will consist of the value attributed to the result (in the case at hand, the remuneration that the employee failed to receive), reduced in accordance with a coefficient that takes into account the degree of probability of achieving such an outcome. These two judgments delineate the loss of chance profi le in very similar terms to those in prevailing French case law. They form the basis of an already extensive series of precedents in the application of the loss of chance within the context of procedures relating to the admission or promotion of employees by their respective employers. Nevertheless, apart from clarifying the pre-contractual or even contractual nature of the liability in question,33 some judgments present developments in what concerns the autonomy and the assessment of the chance for the purposes of compensation.34 Furthermore, the loss of chance theory has also been applied in Italy to the most diverse situations of civil liability, including cases of professional civil liability, particularly where lawyers are concerned.35 For instance, in the judgment of 13 December 2001 (no. 15.759), the Corte di Cassazione reinforced the concept of loss of chance as an actual and specific 31 32 33 34 35 64 Published in 1 GC (1984), p. 1841 et seq., with annotations by E. Cappagli, ‘Perdita di una chance e risarcibilità del danno per ritardo nella procedura di assunzione’. Published in RDCDGO year LXXXIV (1986), No. 5–8, p. 213–219, with annotations by V. ZenoZencovich, ‘Il danno per la perdita della possibilità di una utilità futura’. See Judgments of 22 March 1989 (No. 1441), of 22 July 1995 (No. 8010) and of 6 June 2006 (No. 13241). In particular, in the judgment given on 13 June 1991 (No. 6657), the Corte di Cassazione stressed, contrary to the judgment of 19 December 1985 (No. 6506), that the compensation for loss of chance does not depend on a 50% higher probability of success. The Corte di Cassazione issued other judgments that were similar to this decision – refer to Judgments of 28 May 1992 (No. 6392), of 22 April 1993 (No. 4725) and of 25 October 2000 (No. 14074). Among the books and articles published on this issue, there may be found: G. Giannini and M. Pogliani, La Responsabilità da Illecito Civile – Assicuratore, Magistrato, Produttore, Professionista (Giuff rè, Milan 1996); T. Gualano, in G. Vettori (ed.), Il Danno Risarcibile, p. 349–362; M. Feola, ‘Nesso di causalità e perdita di “chances” nella responsabilità civile del professionista forense’, RCDP (March 2004), p. 151–182; R. Conte, ‘Profi li di responsabilità civile dell’avvocato’, NGCC (Jan./Feb. 2004), p. 144–165; E. Corapi, ‘La responsabilità dell’avvocato’, Guido Alpa et al. (eds.), NGCC – Casi Scelti in Tema di Responsabilità Civile, p. 13–22. 20 MJ 1 (2013) The Loss of Chance in Civil Law Countries: A Comparative and Critical Analysis damage that does not constitute ‘(…) a mere expectation of fact but rather a patrimonial entity in itself, that may be legally and economically subject to an autonomous evaluation (…)’. Taking the chance’s assumption of autonomy to its last consequence, and alleging that the initiation of proceedings or the exercise of a procedural faculty always implies a potential advantage to those who carry it, the Italian Supreme Court also considered that the loss of chance to intent or take legal action in court, either as an active or passive party, determines a damage about which, in general, no problem can be posed with respect to its existence, but only, eventually, through the quantum’s perspective. In this case, the Corte di Cassazione’s decision was based on the assumption of full autonomy of the loss of chance, like that supported in France, in similar cases, by a minority case law trend, and with favourable appraisal by Viney and Jourdan. All in all, giving a general theory for the loss of chance is also found to be impossible in Italy. The concept of loss of chance presents diversified contours according to the respective domains of application and the various court rulings. 2. In medical malpractice As observed in France, the loss of chance theory has also been adopted within the context of civil liability for medical malpractice. However, it is important to begin by mentioning that in Italy the loss of chance is not traditionally used to overcome the difficulties which may arise in proving a causal connection. This has only recently been incorporated into the Corte di Cassazione’s case law. In effect, a summary of the evolution of Italian case law in this domain may be presented as follows: a) In an early stage, the tendency of the civil case law was to reject the compensation claims. According to the parameters that were normally demanded, the causal connection was not considered to be established;36 b) In a second stage, it was possible to identify important judgments, especially under the Corte di Cassazione penal section that condemned doctors and health units (this was the case even when proving with certainty that the existence of a causal connection was not feasible and only a reasonable probability could be evidenced);37 36 37 For example, the judgment issued by the Corte di Cassazione’s civil section on 7th August 1982 (No. 4437). In particular, we refer to the judgment given on 19th July 1991 (No. 371) in the famous Silvestri v. Leone case, which was repeatedly referred to in subsequent court decisions. In this case, two doctors made an incorrect evaluation when the patient was already showing clear signs of tetanus. They prescribed tranquilizers and subsequently diagnosed meningitis incorrectly and the patient died. Although it was proven that, under the circumstances, a correct diagnosis of the disease would only have given the patient a 30% chance of recovery, the Corte di Cassazione confirmed the judgment under appeal. It ruled that a ‘(…) serious and reasonable probability of success in so far as the patient’s life would have been saved with a certain probability’ was sufficient for the outcome to be attributed to the defendants. 20 MJ 1 (2013) 65 Rui Cardona Ferreira c) In the third stage, however, a turning point occurred in the orientation of the Corte di Cassazione, and it adopted a more restrained approach to the causal connection in this group of cases;38 d) In the final stage, and more recently, the Corte di Cassazione began to accept the loss of chance theory, with a view to securing some compensation for the plaintiff in light of the uncertainty of the causal connection.39 These historical developments show that the recourse to the loss of chance, as an autonomous damage likely to be compensated within the context of civil liability for medical malpractice, replaced a more flexible understanding of causation, which in the meantime was abandoned by the Corte di Cassazione. As far as we know, the Italian Supreme Court, through the judgment of 18 September 2008 (No. 23846), accepted a compensation claim based on this theory for the first time.40 3. The civil liability system context The preceding discussion confirms that loss of chance implies possibilities that should not be disregarded in order to overcome a strictly binary logic, which varies between accepting the right to compensation for the overall final damage to refusing any compensation at all. These possibilities have led to an undeniable interest for the loss of chance and an increase in the number of cases accepting this theory in areas 38 39 40 66 Th is turning point was made through three different judgments, with identical outcomes, issued at the end of 2000 – the judgments of 28 September 2000, No. 1688, of 28 November 2000, No. 2123, and of 29 November 2000, No. 2139. The judgment of the Corte di Cassazione, dated 4 March 2004 (No. 4400), was the pillar of this case law, since it accepted the compensation for loss of chance, at least in theory. In this particular case, it was noticeable that the lack of surgical intervention had increased ‘(…) the possibility of a negative outcome (…)’, so that the patient lost ‘(…) the chances statistically proven (…)’ to be saved. The Corte di Cassazione qualified the loss of chance as a ‘(…) specific and effective occasion favouring the achievement of a certain outcome or result (…)’, which does not constitute ‘(…) a mere expectation of fact, but rather a patrimonial entity in itself, that may be legally and economically subject to an autonomous evaluation (…)’ and whose loss represents a ‘(…) specific and actual damage’. Nevertheless, in the end, the Corte di Cassazione refused the compensation for loss of chance for merely procedural reasons: it sustained that the loss of chance was a different claim from the compensation claim for the fi nal damage that was being sought by the plaintiff. In this case, the patient, later on replaced by her heirs, started a civil liability action against the two doctors who had examined her and their respective health unit, and sought compensation for the damage resulting from an inappropriate diagnosis of the disease that caused her death. The Corte di Cassazione ruled that the delay in appropriate administration of palliative care contributed to the deterioration of the patient’s quality of life and premature death (although by only weeks or months) and rendered it impossible for the dying patient to duly organize her remaining life time, which resulted in moral damage that deserved compensation. Taking into account the uncertainty with regard to the degree or extent to which an appropriate diagnosis could have lessened the patient’s pain or prolonged her life, the Corte di Cassazione resorted to the loss of chance concept as an autonomous damage. 20 MJ 1 (2013) The Loss of Chance in Civil Law Countries: A Comparative and Critical Analysis characterized by a radical uncertainty that may scarcely be overcome, as far as the causal process that leads to the final damage is concerned. However, Italian case law tends to adopt vague and imprecise formulae that are constantly referred to as grounds for compensation for loss of chance. It is also observed that different orientations are followed in terms of characterizing the damage at hand. Furthermore, it is noted that the legal decisions present an overwhelming diversity concerning the proceedings and the terms and conditions of the compensation, notably in terms of the degree of probability that is necessary to award the compensation. Nevertheless, the case law description presented here seems to show the configuration of the loss of chance predominantly as an autonomous economic loss. This view, however, is not without ambiguity or controversy, bearing in mind that the compensation – either its existence or at least its amount – depends on the probability of occurrence of the lost chance, as it was referred to with respect to French law. Within the plan of the positive law, the development of the loss of chance seems to be related to the vexata quaestio concerning the limits of the danno injusto’s notion that Article 2043 of the Italian Civil Code refers to. This provision of the Italian civil law remains faithful to the Napoleonic tradition of Article 1382 of the French Civil Code and consecrates an open clause in matters of tortious liability.41 In fact, with regard to the adopted concept of unlawfulness, the only difference between the system that is implemented by Article 2043 of the Italian Civil Code and the Napoleonic tradition of the faute consists of the respective shift from the tortfeasor’s conduct to the damage. Within this context, damage is understood as an offence to a legally protected interest and it is for case law to decide which types of interests or legal situations qualify for compensation when breached. Nevertheless, the theory of loss of chance as an autonomous economic loss cannot be accepted unconditionally for three different reasons. Firstly, it lays its foundations in the assimilation or overlapping of the breached legal situation and the damage that is to be compensated for, whilst loss of chance figures in the plan of damage rather than in the plan of illegality or unlawfulness. Secondly, invoking Article 2043 of the Italian Civil Code identifies the route to access the civil liability system, but does not clarify the 41 Regarding the dano injusto’s notion and the range of the unlawfulness clause in the Italian system of the tortious civil liability, refer to, inter alia, S. Rodotà, Il Problema della Responsabilità Civile (Giuff rè, Milan 1967), p. 84 et seq.; G. Alpa and M. Bessone, Atipicità dell’Illecito (Jovene, Milan 1977), p. 190 et seq. and p. 405 et seq.; G. Alpa and M. Bessone, Trattato di Diritto Privato – 14 – Obbligazioni e contratti (Volume VI, Giappichelli Editore, Turin 1982), p. 74–81; M. Bianca, Diritto Civile – 5 – La Responsabilità (Giuff rè, Milan 1994), p. 582 et seq.; C. Salvi, La Responsabilità Civile (Giuff rè, Milan 1998), p. 58 et seq.; P.G. Monateri, in F. Galgano, Trattato di Diritto Civile, p. 195 et seq.; F. Galgano, Diritto Civile e Commerciale Volume II – Le Obbligazioni e i Contratti (3rd edition, CEDAM, Padua 1999), p. 327 et seq.; G. Alpa, U. Ruffolo and V. Zeno Zencovich, ‘L’ingiustizia del danno. Tipicità e atipicità dell’illecito’, in M. Bessone (ed.), Casi e Questioni di Diritto Privato – IX – Atto Illecito e Responsabilità Civile (8th edition, Giuff rè, Milan 2000), p. 54–139; A. di Majo, ‘Tutela risarcitoria: alla ricerca di una tipologia’, RDC (May/June 2005), p. 243–265; and G. Visintini, Trattato Breve della Responsabilità Civile (3rd edition, CEDAM, Padua 2005), p. 421 et seq. 20 MJ 1 (2013) 67 Rui Cardona Ferreira relevant modus operandi.42 Thirdly, it seems evident that conceiving the loss of chance in light of an open clause of tortious liability, particularly of this magnitude, does not lead to its acceptability in legal systems that are based on different normative terms, as already noted above. When it comes to the causal connection criterion, Article 1223 of the Italian Civil Code stands out. It stipulates that the damage must be presented as an ‘immediate and direct consequence’ of wrongful conduct. This is obviously a provision that is associated with the Napoleonic tradition, and repeats this part from Article 1151 of the French Civil Code. However, as with the case of France, authors show an understandable difficulty in conveying a precise meaning to the expression used by the legislator, focusing more on its meaning than its contents. This meaning results essentially in a restriction of the scope of compensation when compared to the delimitation that would occur from the simple resource to the conditio sine qua non (but-for test) criterion.43 From this perspective, it does not seem possible to frame the loss of chance within legal causation. §3. A. CRITICAL APPRAISAL INADEQUACY OF THE TRADITIONAL FRAMEWORK OF LOSS OF CHANCE Analysing the process of emergence and expansion of loss of chance in the French and Italian systems – the two continental systems in which the recourse to this legal notion is most evident – has enabled us to compile some interesting data and draw a few preliminary conclusions. Nevertheless, it appears that, despite representing a similar functional motivation, loss of chance tends to be regarded in diverse ways, depending on the normative context of the typical situation under consideration and the nature of the final damage it refers to. This will lead to the rejection of a general theory of loss of chance. In particular, when taken from a perspective of economic loss, the conformation of loss of chance as an autonomous damage is largely fallacious, although the alternative qualification as a criterion for the evaluation of causation collides with the parameters usually adopted and, in particular, with the virtually hegemonic demand for a conditio sine qua non. Therefore, one must also take into account the proposals put forward by scholars from other civil law systems, notably the German system, which we will do in the following sections. 42 43 68 In fact, the range of different compensations awarded for the loss of chance depends on the wide margin of discretion that has been given to the judge to identify situations under legal protection. See G. Visintini, Trattato Breve della Responsabilità Civile, p. 681. 20 MJ 1 (2013) The Loss of Chance in Civil Law Countries: A Comparative and Critical Analysis B. ALTERNATIVE PROPOSALS FOR A LEGAL FRAMEWORK 1. The strictly normative concept of loss of chance An alternative proposal for the legal framework of loss of chance consists of what might be qualified as a strictly normative view, which is present in the work of a number of German scholars, notably Nils Jansen. In fact, in an important article on this theme,44 this author aimed to demonstrate that ‘(…) the idea of loss of chance is generally a useful concept for the law of damages and should be adopted by English and German law’, not solely for logical or empirical reasons, but also because what matters is ‘(…) constructing an adequate law’, taking into consideration both systematic internal legal arguments and policy issues.45 Bearing in mind that English and German law present solutions of either all or nothing in cases in which the defendant merely increased the risk of materialization of the damage,46 which might prove to be arbitrary,47 Nils Jansen holds that the idea of loss of chance may constitute an adequate instrument to overcome those obstacles. As to the essence of the phenomenon, Nils Jansen recognizes that loss of chance ‘(…) factually transforms problems of proof of causation into terms of the assessment of damages’,48 but emphasizes that ‘(…) the main point of this idea is normative: (…) it relates to legal rights (norms), and not to causal issues (facts)’.49 In other words, the chance is converted into a right, which, according to the author, has the advantage of dealing ‘(…) with our problem within the parameters of the old concepts of but-for causation, harm, and damages’,50 and avoiding a radical change in the criterion to be adopted with respect to causation. This thesis operates a veritable restructuring of the concept of loss of chance, where compensation is no longer grounded on the supposed value of property or exchange: ‘there is no market for opportunities to renegotiate contracts, there is no market for chances to gain an employment, and the chance of winning a beauty contest can obviously not be sold’.51 The grounds for the loss of chance must be found in the law itself: 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 See N. Jansen, ‘The idea of loss of chance’, 19 OJLS 2 (1999), p. 271–296. By the same author, see Die Struktur des Haftungsrechts. Geschichte, Theorie und Dogmatik ausservertraglicher Ansprüche und Schadensersatz (Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2003), p. 129 et seq. and 596 et seq. Ibid., p. 275. Ibid., p. 277. Ibid., p. 279. Ibid., p. 282. Ibid., p. 283. Ibid., p. 285. Ibid., p. 289. In the last example, Jansen refers to the leading case Chaplin v. Hicks, which historically marks the beginning of the course for loss of chance under English law. In this case, the defendant, who was responsible for the management of a theatre, promoted through a newspaper a contest whose prize was the assignment of ‘theatrical engagements’ to the 12 winners. Six thousand women competed for the contest and the plaintiff was chosen by readers as one of the 50 possible winners, but she was not informed in a timely manner of the interview and the 12 winners were chosen by the defendant without the plaintiff having been granted the opportunity to participate in the fi nal phase of the competition. 20 MJ 1 (2013) 69 Rui Cardona Ferreira (…) the protection of chances is important for the protection of finally endangered rights, since in cases where only a chance is left, there is nothing more to lose than the chance itself. This is the reason why people apparently regard it as very important that law protects these chances. Private law must not fall short in that protection. If tort law does not protect victims against losing chances, it falls short of constitutional demands.52 Among German scholars, Gerald Mäsch holds views similar (or close) to those of Jansen.53 According to this author, who primarily focuses on cases of professional liability of service providers (mainly doctors and lawyers), compensation for loss of chance arises from the breach of a contractual duty of preservation or promotion of the chance. The loss of chance theory should be construed as compensation for an autonomous damage, distinct from the final damage, in order to avoid solutions based on proof facilitation that would lead to an artificially grounded civil liability. According to the understanding of Mäsch, it would not become necessary to operate any alteration or deviation from the usual criterion of causality and the normal requirements of proof, which should not refer to the final damage, but to the autonomous damage of loss of chance. In Mäsch’s view, compensation for loss of chance would not be prohibited under German civil law and, even with a scope limited by the nature of the duties breached, it could play a useful role in overcoming the binary logic of all or nothing, both avoiding the lack of protection or any over-protection of the plaintiff. It should be noted, however, that according to this German scholar, the loss of chance theory may not be admitted in the field of tort liability, since it arises only from the breach of contractual duties. Despite being a significant juridical and scientific breakthrough when compared with the poorly grounded formulae traditionally used in the field of loss of chance, the views of Jansen and Mäsch also appear to be open to some criticism. Essentially, they shift the entire problem to the plan of unlawfulness, in which the true demand of the damage is diluted, and leads to the award of compensation in spite of a change to the economic status of the plaintiff being undetectable. 52 53 70 Despite the inability to demonstrate that the prize would have been achieved but for the misconduct of the defendant, which was qualified as breach of contract, the plaintiff was awarded a compensation of £100 for the loss of chance of winning this competition – see A. Burrows, A Casebook on Contract (2nd edition, Hart Publishing, Portland 2009), p. 346–350. Ibid., p. 292. What the constitutional demands in question are precisely is unclear from the reasoning of Nils Jansen. Helmut Koziol criticizes this argument by writing: ‘before invoking constitutional law to fundamentally reformulate private law in the field of civil liability, it should be considered that there are good reasons to protect, within civil liability, fundamental juridical assets but not chances, on the one hand, and that solutions may be found in private law that conform to the system, on the other hand’ – see H. Koziol, ‘Schadensersatz für den Verlust einer Chance?’, in R. Hohloch, R. Frank and P. Schlechtriem, Festschrift für Hans Stoll zum 75. Geburtstag (Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2001), p. 233–250, p. 246 et seq. See G. Mäsch, Chance und Schaden (Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2004), p. 240 et seq. and p. 320 et seq. 20 MJ 1 (2013) The Loss of Chance in Civil Law Countries: A Comparative and Critical Analysis In this context, compensation may be awarded despite the inexistence of a true economic loss. This is particularly obvious in cases of medical malpractice,54 but even in other cases the chance whose loss is compensated could hardly be regarded as having an inherent and autonomous economic or market value.55 In other words, according to these scholars and for strictly normative reasons, compensation should be granted beyond or irrespectively of an actual economic loss. Consequently, in our view, this understanding is admissible only when the damage assessed in this way is of a non-patrimonial nature. The core idea would be, for example, that life’s legal protection is so intense that the mere causal contribution to the corresponding damage should not fail to be sanctioned, especially when the injurer has a duty to use his or her diligence to safeguard it. Diversely, there seems to be no reason to consider that the chance of acquiring a right or an advantage of economic nature is so intensely protected by law (either under tort or contractual law) that the mere breach of the relevant duties automatically entails a right to compensation (without evidencing that this right or advantage would otherwise have been effectively acquired). Taking into account that Jansen’s and Mäsch’s theories should only apply to damages of a non-patrimonial nature, it becomes apparent that they will not serve to justify a compensation for damages of loss of chance, whenever the latter should be regarded as an economic loss. Thus, this theory offers a satisfactory solution to only one part of the problem, by imposing a differentiation for damage of loss of chance depending on the group of cases under consideration and the nature (patrimonial or otherwise) of the relevant damage. From our perspective, there is truly only autonomous damage – thus relatively independent of the degree of probability of the materialization of chance – in the cases of compensation for non-patrimonial damage. In such cases, the scope of normative protection of the interests in question may justify the award of compensation for an autonomous damage of loss of chance, which will typically take place in the cases of civil liability for medical malpractice. In other situations, and no matter how difficult it may be, the test of admissibility of loss of chance has to be considered at a causation level. 54 55 Th is is why other German scholars expressly refuse the construction of loss of chance as an autonomous damage in the context of medical malpractice – see H. Stoll, ‘Schadensersatz für verlorene Heilungschancen vor englischen Gerichten in rechtsvergleichender Sicht’, in E. Deutsch, E. Steffen and E. Klingmüller, Festschrift für Erich Steffen zum 65. Geburtstag am 28. Mai 1995 – Der Schadensersatz und seine Deckung (De Gruyter, Berlin/New York 1995), p. 475; M. Kasche, Verlust von Heilungschancen – Eine rechtsvergleichende Untersuchung (Peter Lang Publishing, Frankfurt am Main 1999), p. 224 et seq.; and L. Röckrath, Kausalität, Wahrscheinlichkeit und Haftung (Rechtliche und ökonomische Analyse) (Verlag C.H. Beck, Munich 2004), p. 112 and p. 180–181. See footnote 57 below. 20 MJ 1 (2013) 71 Rui Cardona Ferreira 2. The idea of alternative causation It is worth thinking about Koziol’s reflections on this topic. Koziol rebutted the feasibility of qualifying loss of chance as an autonomous economic loss within the context of the German civil liability system.56 According to this author, the idea of autonomy of chance is contradicted by the enshrinement in German law of a subjective concept of damage – to be established by resorting to the ‘method of difference’ (Differenzmethode) –, to which is added, in many cases, the impossibility of giving it an ‘individual, autonomous and appraisable value’.57 Hence, in such cases, what would in fact be at stake is a problem of uncertainty regarding the unfolding of the hypothetical causal sequence (that would have occurred, if the chance had not been destroyed).58 In an attempt to re-regulate the loss of chance in accordance with the system, Koziol eventually agrees with the opinion expressed by some German scholars regarding civil liability for medical malpractice,59 recognizing that, in cases typically framed within the loss of chance, the awarding of a partial compensation to the plaintiff is justified, notably considering the preventive function of liability: ‘(…) in cases of clear illicit and culpable conduct, there are no reasons to grant exemption of liability to the injurer due to the impossibility of clarifying the causal connection’.60 In essence, Koziol proposes the use of ‘alternative authorship’ rules (alternative Täterschaft) or the underlying idea of ‘co-liability’ (Mitverantwortung) to ensure the plaintiff partial compensation in cases in which there are a number of causes regarding the final (and only) damage to compensate: it would be supported both by the injurer, in the sense that it was caused by the injurer’s illicit conduct, and by the plaintiff, in the sense that it results from a competing cause within the very domain of risk.61 The author provides an example: if a physician does not begin the treatment early enough the patient may die due to omission of treatment, i.e. a factor that generates liability, or by an underlying medical condition, in other words, a circumstance that is within the scope of patient’s risk [‘Risikobereich’]. What 56 57 58 59 60 61 72 H. Koziol, in R. Hohloch, R. Frank and P. Schlechtriem, Festschrift für Hans Stoll zum 75. Geburtstag, p. 239 et seq. Ibid., p. 240–242. Th is confirmation reflects the confrontation between the functional unit of the loss of chance, on the one hand, and the diversity of situations in which it operates, on the other hand. In fact, Koziol provides a very enlightening example: ‘A farmer orders a substance for the protection of his plants that, if applied at the right time, possibly would have saved his parasite infested crops. The supplier does not provide the substance on time and the treatment is started too late; it is no longer possible to confirm if the plants could have been saved in case of timely application. Here it is not about the loss of a chance that represents an autonomous economic value, but a negative effect on property’, – ibid., p. 241. Ibid., p. 243. See H. Stoll, in E. Deutsch, E. Steffen and E. Klingmüller, Festschrift für Erich Steffen zum 65. Geburtstag am 28.Mai 1995 – Der Schadensersatz und seine Deckung, p. 472 et seq.; and M. Kasche, Verlust von Heilungschancen – Eine rechtsvergleichende Untersuchung, p. 255 et seq. Ibid., p. 247. Ibid. 20 MJ 1 (2013) The Loss of Chance in Civil Law Countries: A Comparative and Critical Analysis is special is when an incident that generates liability competes with an incident from which no liability arises (…).62 As the author explains, this point of view is rooted in the rule that when there are several possible agents of illicit and culpable conduct and it is not possible to identify the author of the damage, all must be held jointly and severally liable without prejudice to the right of recourse. In order to do so, the only requirement is to demonstrate that the conduct of each of the agents, apart from the conduct of others, might have caused the damage, taking into account the danger specifically created and the materialization’s degree of probability of the damage that actually occurred. Koziol defends the extension of the same perspective to situations in which instead of alternative illicit conduct by several agents, there is a confluence of illicit conduct, on the one hand, and factors that are within the realm of risk of the plaintiff, on the other hand.63 This is also a reconstructive theory of loss of chance of undeniable juridical and scientific interest, which is normatively based – although different from that expressed by Jansen and Mäsch – and this produces the desired practical effect of overcoming the binary logic of all or nothing. Moreover, the corresponding justification, although related to cases of civil liability for medical malpractice, is applicable tow cases in which the loss of chance regards property assets or economic advantages, unlike, in our view, Jansen’s and Mäsch’s theories. However, this construction is closely connected to or dependent on the existence of, in the legal system in question, a rule similar to §830 I in the German Civil Code, which specifically allows for the liability of the co-author or participant even without establishing a causal connection between the respective conduct and the damage occurred (it only requires a mere potential or alternative relation of causation). Therefore, the theory defended by Koziol does not hold universal validity or application either. §4. CONCLUSION: THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN THE NATURE OF THE DAMAGE AND THE NEED FOR A CIVIL LIABILITY SYSTEM OF LIMITED MOBILITY In summation, there appears to be a functional dimension underlying all situations in which loss of chance is used, which consists of the figuration of the intermediate damage to be compensated, when the standards that are usually required do not allow for causation between the harmful conduct and the final damage to be established. On the 62 63 Ibid., p. 247–248. According to the author, this construction is recognized by the Austrian Supreme Court, following the view of Bydlinski – see F. Bydlinski, ‘Haft ungsgrund und Zufall als alternativ mögliche Schadensursachen’, in G. Frotz, M. Enzinger and H.F. Hügel, Aktuelle Probleme des Unternehmensrechts – Festschrift für Gerhard Frotz (Manz, Wien 1993), p. 3 et seq., apud Koziol, in R. Hohloch, R. Frank and P. Schlechtriem, Festschrift für Hans Stoll zum 75. Geburtstag, p. 248, note 65. Ibid., p. 248–249. 20 MJ 1 (2013) 73 Rui Cardona Ferreira other hand, the material characterization of loss of chance and the admissibility of the corresponding autonomy as to the final damage must take into account the typical case under evaluation and, notably, the nature of such damage. Thus it may justifiably be said that the creation or adoption of loss of chance arises from a common problem in all cases of civil liability to which it may be applicable – and this is unarguably and unquestionably a causation problem. However, it should be added that the construction of an autonomous damage may be successful or unsuccessful, depending on the normative framing and the nature of the final damage whose compensation loss of chance is a substitute for. Consequently, the independence of loss of chance as to the materialization degree of probability of the advantage to which it refers to, and the consequent autonomy of the damage in question – even if admissible in the context of compensation for noneconomic loss – may not be extended to situations of an economic nature. When of an economic nature, loss of chance may not be regarded as an abstract and autonomous damage, but always depends to a greater or lesser extent on the probability of the final damage occurring, which is truly the only damage to be compensated. This distinction makes perfect sense both at a theoretical level and in terms of practical consequences, since the full or nearly full autonomy of chance stems from the inversion of the assumption of its corresponding seriousness (as defined by French case law and scholars), by admitting the possibility of compensation for loss of chance whenever it proves to be, to some extent, relevant to the production of the outcome. The risk of expanding the economic loss to be compensated ad infinitum, without sound normative grounds, is obvious. In this last field, the compensation for loss of chance, precisely because it should not be regarded as an autonomous damage, must not dispense with the demonstration of a relevant degree of probability to be determined according to normative and value judgements. This requires the notion of civil liability as a movable system64 in which the criterion of causation may have different configurations or variable intensity. Indeed, if the prevalence of conditio sine qua non has the advantage of tradition and the weight of an individualistic society, today it must be put to the test of adequacy of value, in agreement with the juridical values at stake and the normative context of the situation of civil liability in question. The requirement of a conditio sine qua non may then prove excessive or even contrary to the law’s purposes and the interests which it aims to protect. And this hypothesis is more and more likely to occur in a modern and increasingly complex and interdependent society. Knowing in which precise groups of cases this is admissible and the exact degree of probability required for causation to be met, even when below the threshold of condition sine qua non, are still questions with incomplete answers and constitute a challenge to be met by jurists and legal science in the future. 64 74 See W. Wilburg, Entwicklung eines beweglichen Systems im Bürgerlichen Recht (Kienreich, Graz 1950); and W. Wilburg, Die Elemente des Schadensrechts (Elwert, Marburg a.d. Lahn 1941). 20 MJ 1 (2013)