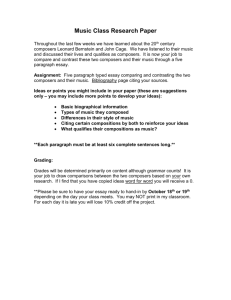

June - 21st Century Music

advertisement