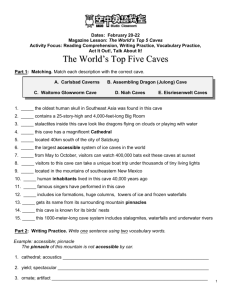

051 (Apr-Sep 1982) (combined issue)

advertisement