ENTERTAINING GHOSTS - DRUM

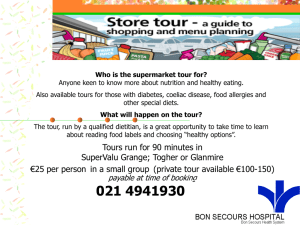

advertisement