Contracts:

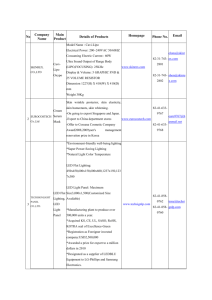

advertisement

Contracts: Kinds of Contracts: - Executory Contract - Obligations are not enforceable immediately - Executed Contract - Immediately fulfilled upon entry - Partly Executed Contract - Some obligations fulfilled, some remaining to be fulfilled - A contract must have three requirements: 1. Offer 2. Acceptance 3. Certainty of Terms - Avoided Contract - A contract was in place but it has been brought to an end - Voided Contract - A contract that lacks validity and has no legal force - Treated as though it never existed - Common Law concept - Remedy in $$ - Voidable Contract - If a contract existed, it is set aside by innocent party - Equitable concept - Remedy in injunctions or specific performance Offer: - All terms of the contract must be in the offer - Intention test for offer: 1. Action speaks louder than words 2. What would a reasonable person say the intention was? - There must be an intention to be bound by the terms - There must be certainty of terms present in offer - Mere puff is an offer that no reasonable person would take seriously - Not legally binding - Transactions by machines are offers - Auctions without reserve are offers Communication of Offer: - Offers cannot be effective until they are communicated to the offeree - You cannot accept an offer you did not know existed (R v. Clarke) - Knowledge, without intention to accept, is sufficient to accept (Williams v. Carwardine) - This is countered in (R v. Clarke), but that was likely for policy reasons - There must be intention to create legal relations (Blair v. Western Mutual Benefits Association) Invitation to Treat: - Price quotations are usually invitations to treat (Canadian Dyers Association Ltd. v. Burton) - Display of goods, as in a store, is invitation to treat (Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v. Boots Cash Chemists Ltd.) - Unless cashier does not have authority to accept offers (R v. Dawood) - A contract is not a valid defence to theft (R v. Dawood) - Advertisements are typically invitation to treat, unless construed as offer by reasonable person (Carhill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Ltd.) - Must have all components of offer (Goldthorpe v. Logan) Acceptance: - Must be communicated - Must be absolute - Must correspond to all terms of offer - Acceptance that changes the terms in any way is a counter-offer (Livingstone v. Evans) - Inquiries do not kill the offer (Livingstone v. Evans) - Must be a meeting of the minds (Carhill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Ltd.) - In a battle of the forms, the terms on the last form signed win (Butler Machine Tool v. Ex-Cell-o-Corp.) - If terms of contract cannot be reconciled, the contract cannot exist (Butler Machine Tool v. Ex-Cell-O-Corp.) Communication of Acceptance: - Requirements for acceptance to be valid: 1. Must have conscious knowledge that offer is being accepted (R v. Clarke) 2. Must have conscious knowledge of the offer itself (Williams v. Carwardine) 3. Acceptance must be communicated to offeree - Exceptions to communication of acceptance: 1. Waiver of Communication a) Express or implied intimation that a certain kind of acceptance will suffice (Carhill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Ltd.) b) There must be an overt act on part of offeree to prove acceptance 2. Promise for an Act a) Performance of contract is acceptance 3. Postal Acceptance Rule a) Applies to government post and telegrams only (Household Fire & Carriage Accident Insurance Co. v. Grant) b) Post office is agent of offeror c) Offer is accepted when it is handed to post office d) Contract is formed where letter is received (Brinkibon Ltd. v. Stahag Stahl Und.) e) If a contract states acceptance must be received by offeror, postal acceptance rule cannot apply (Felthouse v. Bindley) f) If application of the rule is absurd, it will not apply (Holwell Securities v. Hughes) 4. Acceptance by Silence a) It may stipulate in offer that silence is appropriate for acceptance (Carhill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Ltd.) b) Cannot result in burden being placed on offeree (Felthouse v. Bindley) Termination of Offer: - Offers are terminated in three ways: 1. Revocation 2. Rejection 3. Lapse of Time Revocation of Offer: - Communication on part of offeror that offer is no longer open - Offers open to the world should be revoked by same means they were made (Carhill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Ltd.) - Not effective until it is communicated (Dickinson v. Dodds) - Once revocation is communicated, offer can no longer be accepted (Dickinson v. Dodds) - Postal Acceptance Rule does not apply here (Byrne v. Van Tienhoven) - An offer may be revoked any time before acceptance (Dickinson v. Dodds) - Acceptance makes an offer irrevocable - Consideration for a promise binds an offeror to keep an offer open (Dickinson v. Dodds) Rejection: - A counter-offer is a rejection of an original offer (Livingstone v. Evans) - Can only be done by offeree Lapse of Time: - A promise to keep a contract open is only binding if consideration is given (Dickinson v. Dodds) - Parties may agree on a time in which acceptance must take place (Barrick v. Clarke) - Passage of time can end an offer (Barrick v. Clarke) - It depends on the nature of surrounding circumstances - Reasonable person test applies (Barrick v. Clarke) (Manchester Diocesan Council v. Commercial and General Investments) - How long would a reasonable person have kept offer open? - How long would a reasonable person have taken to accept? - Must consider intervening events to determine what is reasonable (Manchester Diocesan Council v. Commercial and General Investments) Unilateral Contracts: - An act is done in return for a promise - Only one party is required to do something - Typically in reward situations (Carhill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Ltd.) - Acceptance is communicated by fulfilling requirement for act - Contract does not exist until act is completed - Revocation must take place before act is completed (Errington v. Errington & Woods) 1. If actions have been taken towards partial completion, law of restitution will apply. 2. You must show offeror was unjustly enriched 3. An argument can be made that a preliminary contract was made 4. Can also argue contract was bilateral, do this in framing of contract (Errington v. Errington & Woods) Certainty of Terms: - Must exist at the time of acceptance - “Canon of Constructions” clarifies what parties legally mean - If an aspect of the offer is unclear/not present, one of the following will apply: 1. Strike-Out Clause a) Unimportant clauses will be eliminated (Nicolene Ltd. v. Simmonds) 2. Interpret Clause a) Uncertain terms are clarified in reference to original agreement or normal practice (Hillas and Co. v. Arcos Ltd. House of Lords) b) Intention can be used to interpret terms (Foley v. Classique Coaches Ltd.) 3. Contract Will Fail a) If parties do not agree on terms (Courtney and Fairburn Ltd. v. Tolaini Bros. Ltd.) b) If a crucial term is not determined, like the price (May and Butcher Ltd. v. R) (Hillas and Co. v. Arcos Ltd. Court of Appeal) c) An agreement to agree is not a contract (Empress Towers Ltd. v. Bank of Nova Scotia) (Mannpar Enterprises v. Canada) - Contracts will be upheld whenever possible (Foley v. Classique Coaches Ltd.) Agreement to Renew: - There is an obligation to negotiate in good faith (Empress Towers Ltd. v. Bank of Nova Scotia) - Unless there is no mechanism for determining price (Mannpar Enterprises v. Canada) - Agreement cannot be withheld unreasonably (Empress Towers Ltd. v. Bank of Nova Scotia) Sale of Goods Act: - The price in the contract can be set in the following ways: 1. The contract itself (Sale of Goods Act s.12(1)) 2. An agreed-upon method (Sale of Goods Act s.12(1)) a) To agree later (Sale of Goods Act s.12(1)) b) Reference to market price (Sale of Goods Act s.12(1)) c) A third party may set the price (Sale of Goods Act s.12(1)) (1) If the third party cannot or does not set a price, there can be no contract (Sale of Goods Act s.13) (2) If there has been some delivery of terms, a reasonable price will be charged for those (Sale of Goods Act s.13) d) Reference to another contract (Sale of Goods Act s.12(1)) 3. The Reasonable Price (Sale of Goods Act s.12(2)) a) This depends on the circumstances of the case Intention to Create Legal Relations: - Determined by the reasonable person test - Family agreements and social engagements cannot be contracts (Balfour v. Balfour) - This hurts the weaker party (Balfour v. Balfour) - An explicit statement not to create legal relations renders the contract not binding (Rose & Frank v. JR Crompton & Bros.) Consideration: - A seal acts as consideration in a formal contract (Royal Bank v. Kiska) - Consideration exists for promises in a contract, not a contract itself - The following can be valid consideration: 1. An act in exchange for a promise 2. A forebearance a) Promise not to sue is not valid if there is no legal merit to claim (B. (D.C.) v. Arkin) 3. The creation, modification, or destruction of a legal relationship 4. A promise - The existence of consideration must be distinguished from the following: 1. Motive a) Love and affection is not the same as consideration (Thomas v. Thomas) 2. Adequacy of consideration a) Must be something of value in the eyes of the law (Thomas v. Thomas) b) The size of consideration does not matter 3. Failure of consideration - Past consideration is no consideration (Eastwood v. Kenyon) 1. Except in emergency situations (Lampleigh v. Braithwait) 2. The terms must be explicit for emergency situations (Lampleigh v. Braithwait) - Pre-existing legal duty is not valid consideration 1. Promises to a 3rd party can be valid consideration if they have not already been performed (Pao on v. Lau Yiu Long) - Mutual abandonment of agreements is not valid consideration (Gilbert Steel v. University Construction) Changing the Promise as Consideration: - This may occur in two situations: 1. Replacing the contract with a new one 2. Replacing a term in the contract - Accord in Satisfaction: 1. Consideration replaces an old prior agreement 2. Enforceable as long as there are new promises made (Foot v. Rawlings) The Same Promise for More or Less: - The same promise for more: 1. Not enforceable if what is being received does not change (Gilbert Steel v. University Construction) - Making the same promise for less 1. Not enforceable if what is being received does not change (Foakes v. Beer) (R v. Selectmove Ltd.) a) There are four ways around this: (1) Put an agreement under seal (2) Use the Law and Equity Act, which eliminates Foakes v. Beer (3) Make something else in the contract different, like time of payment or method of payment (Foot v. Rawlings) (4) Use estoppel to enforce a promise Law and Equity Act: - Part performance of an obligation, if accepted as satisfaction, extinguishes an obligation (Law and Equity Act s.43) Promissory Estoppel: - From the court of equity - Must be a statement of fact (Central London Property Trust Ltd. v. High Trees House Ltd.) - There must be a reliance on the statement (Central London Property Trust Ltd. v. High Trees House Ltd.) - It helps if the person relying on the statement suffers a detriment - Restricted by the following: 1. Waiving rights in the past does not mean they will be waived in the future (John Burrows Ltd. v. Subsurface Surveys Ltd.) 2. It must be fair to enforce the promise (D&C Builders Ltd. v. Rees) 3. Estoppel is a shield, not a sword (Combe v. Combe) a) You can bring an action if you want to seek the right to use estoppel as a defence (Robichaud v. Caisse Populaire De Pokemouche Ltee) b) An Australian High Court has found that estoppel can be a sword (Walton Stores Pty. Ltd. v. Maher) Privity: - The only persons who can enforce a contract are the parties to a contract (Tweddle v. Atkinson) (Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co. Ltd. v. Selfridge & Co. Ltd.) (Beswick v. Beswick) - Obligations can only be imposed on parties to the contract - There are two forms of privity: 1. Horizontal Privity (Tweddle v. Atkinson) (Beswick v. Beswick) a) A contract made by A&B for benefit of C 2. Vertical Privity (Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co. Ltd. v. Selfridge & Co. Ltd.) a) A&B have a contract, B&C have a contract, but A does not have a contract with C Circumventing Privity: - There are a number of ways to get around the privity doctrine: 1. Abolish the situation by statute 2. Try to use Civil Law Vertical Privity Rule a) This is only persuasive, not binding b) When A sells to B, A sells a guarantee. When B sells to C, the guarantee goes with it. C can bring an action against A. 3. Constructive Trust (Horizontal Privity) a) If A requires B to act for the benefit of C, it creates a fiduciary duty between B and C b) A fiduciary duty is stronger than a contract 4. Agency (Vertical Privity) a) B is acting as an agent between A and C b) The contract would effectively be between A and C 5. Specific Performance 6. London Drugs Exception (London Drugs Ltd. v. Khuene & Nagel International Ltd.) a) Can be used only as a defence b) Does not apply only to employment contracts (Fraser River Pile & Dredge v. Can-Dive Services) (1) The provision that applies to a third party must exist at the point the 3rd party can utilize it c) In an employment contract between A and B, if the employee is acting on behalf of the employer, a contract can be extended to an employee in the following circumstances: (1) If the limitation clause explicitly or impliedly extends to employees (Edgeworth Construction Ltd. v. ND Lea & Ass. Ltd.) (2) If the employee was acting in the course of employment (3) If the employee was performing very services of contract Requirement of Writing: - Contracts for land must be in writing and signed (Law and Equity Act s.59(3)(a)) - A guarantee is not enforceable unless it is in writing and signed (Law and Equity Act s. 59(6)(a)) - A contract that cannot be enforced can be ordered to be solved in restitution and compensation for money spent relying on the contract may be ordered. (Law and Equity Act s. 59(5)) Misrepresentation: - Representations that are not true - They arise in the law of torts, not contracts - Operative Misrepresentation A. Must be a statement of fact B. Must be a statement that is false 1. Silence is satisfactory if: a) There is a fiduciary duty b) A question is asked but silence is the response c) A statute makes it a personʼs duty to disclose C. A statement must be addressed to a party to the contract D. Representation must induce the contract - Three kinds of misrepresentation: 1. Innocent 2. Negligent 3. Fraudulent - A party cannot rely on a misrepresentation if he has taken steps to investigate (Redgrave v. Hurd) - Opinion is the same as fact if the facts are not equally known (Smith v. Land and House Property Corp.) Helpful Chart to Determine Remedy: Kind of Misrep. Damages (Common Law) Recision (Equity) Innocent No. Yes. Negligent Yes. Yes. Fraudulent Yes. Yes. Recision: - The undoing of the contract - Both parties are restored to their position, had the contract never occurred - The following things may prevent recision: 1. Recision may upset third party rights 2. There is an impossibility of complete restitution a) This is countered in (Kupchak v. Dayson Holdings BCCA) 3. If a party took an action that affirmed the contract, even though they were aware of the misrepresentation 4. The contract has been completed (this is weak) - If repudiation is rejected, you cannot claim recision (Leaf v. International Galleries) Classification of Terms: - A term is intended to be guaranteed strictly (Heilbut, Symons & Co. v. Buckleton) - Terms are subdivided into three categories A. Conditions 1. Statements of fact that are essential to the contract 2. Remedy in damages and repudiation B. Intermediate Terms 1. Innominate (not named or classified) 2. Remedy is based on seriousness of breach (Hong Kong Fir Shipping Co. v. Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd.) C. Warranties 1. Not essential to main intention of contract 2. Only remedy is in damages unless otherwise stated - Intermediate terms can be included in the Sale of Goods Act (Hong Kong Fir Shipping Co. v. Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd.) (Krawchuk v. Ulrychova) - Placing labels on terms does not define them; this is a job for the courts (Wickman Machine Tool Sales Ltd. v. Schuler AG) Recision or Repudiation? Recision Repudiation Remedy For: Misrepresentation Breach of Contract Type of Remedy: Equitable (therefore no right to the remedy) Common Law (therefore there is a right to a remedy) Action: Ends the contract; restores parties to original position Ends contract; innocent party can terminate primary obligations Comments: You will do well on this exam. This remedy is often lost if it is not acted on right away. Entire or Severable Obligations: - Severable contracts can be cut into smaller portions - Entire obligations cannot be broken down - “Blue Pen Test”: If the judge can draw a line through the obligations, the contract can be severed - An obligation must be substantially performed to be performed (Fairbanks v. Shepard) - Quantum Meruit 1. If an innocent party takes benefit from work, he may be liable anyway (Sumpter v. Hedges) 2. Even if the obligations of the contract have not been performed, a party can be compensated for work done (Cutter v. Powell) Excluding and Limiting Liability: - Terms can be read into a contract based on custom, usage, business efficiency, or presumed intention (Matchinger v. Hoj Industries) - Terms can make the interpretation of a contract difficult (Scott v. Wawanesa Mutual Insurance Co.) - Certain provisions at Common Law can limit liability 1. Exclusion (excludes liability) 2. Limitation (limits liability) 3. Procedural (imposes a procedure that the law does not) - Notice Requirement 1. There must be awareness of a clause in order to be bound by it (Parker v. SE Rwy Co.) (Thornton v. Shoe Land Parking) 2. Reasonable measures must be taken to give notice (Tilden Rent-A-Car v. Clendenning) 3. Notice does not have to be specific, just general 4. Signing a document does not constitute notice 5. If notice is met then exclusion/limitation is valid 6. Previous dealings can constitute notice (McCutcheon v. David MacBrayne Ltd.) - Fundamental Breach 1. If there is a fundamental breach, a limitation clause cannot apply (Karsales v. Wallis) 2. This doctrine is no longer valid in Canada (Hunter Engineering v. Syncrude) (Photo Production v. Securicor) 3. Jurisprudence and legislation on this topic only exists in England - Unconscionability 1. Use strict construction of a clause if there is not unconscionability (Hunter Engineering v. Syncrude) 2. Inequality in bargaining power will cause the limitation clause not to apply (Hunter Engineering v. Syncrude) Application of Exclusion/Limitation Clause: - Follow this test to determine if an exclusion/limitation clause applies: (Hunter Engineering Co. v. Syncrude Canada Ltd.) 1. Is the clause part of the secondary obligations or does it characterize the primary obligations? 2. Is the clause prohibited or regulated by statute? 3. Was there notice of the clause? 4. What does the clause mean? 5. Then, apply the unconscionability test and the unfairness test Unconscionability/Unfairness: - This is from (Hunter Engineering Co. v. Syncrude Canada Ltd.) - The result will be the same whether you look at unconscionability or unfairness (Solway v. Davis Moving Co.) - Was there inequality at the time of acceptance? - If there was not, apply the unfairness test 1. What happened subsequent to the contract being formed? 2. Would it be fair to apply the exclusion clause? - This test has not been received well because it treats commercial contracts the same as any other contract Parol Evidence: - If a contract is in writing and appears complete, a court will not hear parol evidence - Lower courts tend to ignore this rule, as it seems unfair - Written evidence is always stronger than parol evidence (Gallen v. Butterley) - Exceptions: 1. Does not apply if oral evidence adds to, varies, or subtracts from written agreement, rather than contradicting it 2. If it looks like a duck and talks like a duck, then itʼs a duck 3. Unique documents form stronger presumptions than standard ones 4. If specific oral evidence contradicts a general clause, it will be considered more strong Rectification: - The writing is not the contract, but evidence of it - Writing can be changed by court order - An argument for rectification asks the court to change writing of contract - Rectification must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt (Coderre (Wright) v. Coderre) - Subsequent actions of the parties can be used to determine what the contract was (Bercovici v. Palmer) Mistake: - One of the parties did not think the contract said what it did - Can void a contract as though it never existed - Can make a contract voidable and it will come to an end - This is not absolute law - Assumptions outside the contract are normally irrelevant (Smith v. Hughes) - Parties can be mistaken in the following areas: (Bell v. Lever Bros. Inc.) 1. Identity of contracting parties 2. Existence of subject matter of contract at time of acceptance 3. Subject matter at time of acceptance - Mistake can operate at common law or in equity (Solle v. Butcher) 1. At common law, the contract is rendered void. 2. At common law, interpretation of the contract is used to determine whether mistake operates 3. There is now no more equitable doctrine of mistake for Common Mistake (Great Peace Shipping v. Tsavliris Salvage) 4. In equity, a contract is rendered voidable 5. In equity the following determines mistake: a) Party must be induced by material representation b) Defendant must let Plaintiff remain mistaken knowingly - The outcome of an action in mistake is unpredictable (Lindsey v. Heron & Co.) - Mistaken Terms: 1. Usually resolved under Certainty of Terms 2. Unilateral mistakes must not be intentional (clean hands rule), and are resolved in equity (Glasner v. Royal Lepage Estate Services Ltd.) 3. Cannot excuse non-performance if alleged mistake is a term in the contract (McRae v. Commonwealth Disposals Commission) - Mistaken Identity: (Lewis v. Averay) (Shogun Finance v. Hudson) 1. Mistake in identity is only remedied in equity 2. The contract is voidable unless it interferes with third-party rights 3. There can be no remedy if a third party is adversely affected 4. Resolved in equity - Non est Factum 1. Innocent party cannot be negligent about mistake 2. Negligence is determined through reasonable person test (Saunders v. Anglia Building Society) (Marvco Color Research Ltd. v. Harris) 3. “It is not my deed”: someone must be deliberately misled into entering the contract 4. Remedy makes the contract void - There are three kinds of mistake: 1. Common Mistake a) Both parties are mistaken about the same thing b) Will not render a contract void unless it is substantially different or impossible (Great Peace Shipping v. Tsavliris Salvage) 2. Mutual Mistake a) Both parties are mistaken about different things 3. Unilateral Mistake a) One party is mistaken b) Usually looks like fraud Frustration: - In an exam, always argue both frustration and non-frustration - Circumstances have made contract not performable - Non-performance of contract is not self-induced (Maritime National Fish v. Ocean Trawlers Ltd.) (Capital Quality Homes Ltd. v. Colwyn Construction Ltd.) - Contract must be radically different from what was intended - Must be unforseen (Davis Contractors v. Fareham U.D.C.) (Capital Quality Homes Ltd. v. Colwyn Construction Ltd.) - Must not be based on an implied term (Davis Contractors v. Fareham U.D.C.) - Frustration must be of equal significance to both parties (Davis Contractors v. Fareham U.D.C.) - Brings contract to an end (voidable) - Primary and secondary obligations are ended with frustration - Contracts relying on frustrated contract will likely be frustrated as well - When an item perishes and contract is impossible to perform, parties are excused from performing obligations (Taylor v. Caldwell) - Economic problems and labour conditions do not normally cause frustration (Can. Govʼt. Merchant Marine Ltd. v. Can. Trading Co.) - A change in legislation can cause frustration (Capital Quality Homes Ltd. v. Colwyn Construction Ltd.) - This has a high standard of proof (Victoria Wood Development Corp. v. Ondrey) Frustrated Contract Act: - Does not apply to (FCA s.1(2)) 1. Contract of carriage of goods by sea, except in the case of death 2. Insurance 3. Contracts made before May 3 1974 - Only applies if contract has been frustrated (FCA s.1(1)) - Only the courts can define what is frustration (FCA s.1(1)) - Only applies if contract does not have clause dealing with frustration (FCA s.2) - Applies to government and its agencies (FCA s.3) - Blue pen test applies to frustrated contracts (FCA s.4) - If a judge can cut contract up into smaller contracts, frustration will only apply to those smaller contracts that are frustrated - Every party to whom the Act applies is entitled to restitution for benefits (FCA s.5(2)) - Party who partially performed an obligation is entitled to restitution (FCA s.5(2)) - Restitution is reasonable, but not actual expenditures (FCA s.7(1)) - Benefits and costs that are returned are not calculated into restitution (FCA s. 7(2)) - Must NOT take into account loss of profits (FCA s.8(a)) - Secondary obligations survive if a damages claim is initiated (FCA s.5(3)) - Restitution value is reduced if value of benefits is reduced (FCA s.5(4)) - Frustrating event must be cause of value reduction (FCA s.5(4)) - Does not apply if an implied term, custom, or usage dictates that a party must bear loss of frustration (FCA s.6(1)) - Does not apply if a party has insured against this loss in the past (FCA s.6(2)) - Does not apply if parties are expected by their industry to have insurance or be aware of it (FCA s.6(3)) - If you werenʼt expected to have insurance, double compensation is possible (FCA s.8(b)) - Loss of insurance must NOT be taken into account when determining value of restitution (FCA s.8) - The Act is subject to a limitation period and actions must be filed within that time (FCA s. 9) Does the Frustrated Contract Act Apply? (THIS IS THE TEST) - Is the contract frustrated? - If not, Act cannot apply - Did it take place before 1974? - If so, Act cannot apply - Does the contract specify what would take place in case of frustration? - If so, Act cannot apply - Is there an implied term, custom, or usage that party performing should bear cost of frustration? - If so, Act cannot apply - Has there been insurance against this type of loss in the past? - If so, Act cannot apply - Does the industry in which the performing party is working expect insurance? - If so, Act cannot apply - Is the limitation period on the contract up? - If so, Act cannot apply Awards for Frustrated Contracts: - Each party is expected to receive some sort of remedy - Any lost value is split equally between parties - Unless s.6 applies, in which case, no remedy will be awarded - Awards will only be granted for unjust enrichment, not lost profits - Returned benefits are subtracted from the award - Loss of insurance money cannot be considered in the award Insurance in Frustrated Contracts: - Contract was probably not frustrated in the first place, because event was foreseeable - Frustrated Contracts Act does not apply to all insurance - Courts take a narrow reading of insurance that applies to contracts - Insurance is not expected to cover unforeseen damages, but damages generally Duress: - Duress must exist at the time in which the contract was entered - Duress at common law makes the contract void - Duress in equity is more common - This makes the contract voidable - This can also make some obligations not enforceable - There are two kinds of duress: 1. Duress to the Person a) Threats of bodily injury to self, relative, or spouse 2. Duress to Goods a) Also known as economic duress b) Cannot be claimed at common law, only equity (Pao On v. Lau Yiu Long) c) Must be more than mere commercial pressure (Pao On v. Lau Yiu Long) d) Test is as follows (Pao On v. Lau Yiu Long) (Gordon v. Roebuck): (1) Did the party claiming duress protest? (2) Was there an alternative course open to the party? (3) Was the party independently advised? (4) Did the party take steps to avoid the contract, after entering into it? (5) Was the coercion legitimate? (a) It is very difficult to determine legitimate coercion (b) These cases rarely succeed Undue Influence: - Disables a person from acting spontaneously or from independent will - Considers the relationship over time, rather than just the time of the contract - Renders the contract voidable - The test was established in (Geffen v. Goodman) 1. What was the relationship like over time? 2. Was there a possibility for self-determination in the relationship? 3. Was there a fiduciary obligation? 4. Did the influence lead to an unfair contract (commercial contracts only)? 5. Must be rebutted with evidence that contract was of own free will and thought Unconscionability: - Use of power by stronger party over weaker one - Looks at nature of transaction, not at parties - Courts are more likely to find part of contract unconscionable - Two tests for unconscionability: 1. (Morrison v. Coast Finance Ltd) a) Weaker party must demonstrate ignorance, distress, or need b) This must have left him in the hands of stronger party c) Stronger party must have substantial unfairness d) Countered by proof that bargain was fair, just, and reasonable 2. (Harry v. Kreutiziger) / Lambert Test a) Did the transaction as a whole diverge from community standards of morality? b) This is problematic because it asks what the standards of a community are? What is morality? - Unconscionability must exist at time contract is created (Hunter v. Syncrude) (Lloyds Bank v. Bundy) - Often this is grouped together with duress and undue influence (Lloyds Bank v. Bundy) Illegality: - Statutory Illegality 1. The contract is expressly or impliedly prohibited by statute 2. Hinges on legislative intent 3. Direct a) Formulation of contract is illegal b) Contract becomes void/unenforceable c) Consequence is determined by weighing the purpose of the law against the specific purpose of the contract (Still v. Minister of National Revenue) 4. Indirect a) Formulation of contract is not illegal, but consequences of it are b) Not void, but can be argued unenforceable - Common Law Illegality 1. Contrary to public authority 2. These include: a) Contract to commit a legal wrong b) Contracts injurious to public life or legal relations c) Contracts that agree not to go to court, or to oust jurisdiction of court d) Contracts prejudicial to administration of justice e) Contracts that restrict free trade (JG Collins v. Elsley) (1) Must weigh public interest for freedom of contract against competing demands and promoting competition f) Contracts prejudicial to the status of marriage Damages: - Right to damages exists as soon as any obligation is breached - Common Law Remedy - Damages in torts look backward - Damages in contracts look forward - Damages are calculated: 1. At time of breach a) This is the typical time they are calculated 2. At time of judgement a) Market value of land is calculated here (Semelhago v. Paramadevan) b) When damages are awarded instead of specific performance (Semelhago v. Paramadevan) 3. At time of payment of judgement Characterization of Damages: - Interest Protected 1. Expectation a) Money expected to get or save from contract (ie: profits) b) Difficult to quantify because they are profits (McRae v. Commonwealth Disposals Comm.) c) Puts the plaintiff in the position he would have been had the contract been performed (AVG Management Science Ltd. v. Barwell Dev. Ltd.) d) Not usually awarded with reliance benefits (Sunshine Vacation Villas v. The Bay) 2. Reliance a) Puts the Plaintiff in as good a position as he was before contract was made b) Expense incurred because contract was relied on (ie: expenses) c) Used when an expectation interest cannot be determined (McRae v. Commonwealth Disposals Comm.) d) Not usually awarded with expectation benefits (Sunshine v. The Bay) 3. Restitution a) A debt owed by the innocent party - Must be classified as overarching kind: 1. General a) Occur naturally from breach of contract (Hadley v. Baxendale) b) Anyone else that suffered the breach would have suffered same damages (Hadley v. Baxendale) c) Natural, fair, and reasonable (Hadley v. Baxendale) 2. Special a) Contemplated by the breach (Hadley v. Baxendale) b) Probable, reasonable, and predictable (Hadley v. Baxendale) - Must be classified into a head of damage 1. Categories include: a) Loss of profit b) Wasted expenditure c) Interest d) etc. Quantification of Damages: - General damages are calculated in two ways: 1. (Market value of what was supposed to be delivered) - (market value of what was delivered) 2. (Market price innocent party paid) - (contract price that innocent party was supposed to be paid) - Burden of proof is on plaintiff - Plaintiff has right to damages, even if they are impossible to calculate (Chaplin v. Hicks) - Plaintiff is required to act reasonably to mitigate effects of breached contract (Nu-West Homes v. Thunderbird Petroleums Ltd.) (White and Carter v. MacGregor) - Different judges may come to vastly different conclusions (Groves v. John Wunder Co.) - Damages may be awarded for mental distress due to breached contract (Jarvis v. Swans Tours) (Newell v. CP Airlines) 1. Contract must include a state of mental contentment (Jarvis v. Swans Tours) 2. This might not be good law: a) How to you prove damages? b) How do you calculate damages? Remoteness: - Only damages which are reasonably foreseeable are recoverable (Victoria Laundry v. Newman Industries Ltd.) - Reasonableness is determined by knowledge of party that commits the breach (Victoria Laundry v. Newman Industries Ltd.) - Test for remoteness must be more narrowly applied in contracts than in torts (Koufos v. Czarnikow (The Heron II)) - It is harder to establish liability in torts Limits on Recoverability: - Punitive Damages are rarely awarded (Vorvis v. ICBC) (Wallace v. United Grain Growers Ltd.) - Must be harsh, vindictive, malicious, and reprehensible behaviour (Vorvis v. ICBC) - If there is an actionable wrong, aggravated damages can be awarded for employment contracts (Vorvis v. ICBC) - There must be more compensation for termination of employment that is demeaning (Wallace v. United Grain Growers Ltd.)