Brand & Flavor: An Experimental Investigation with Vodka

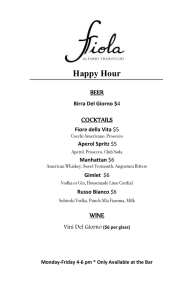

advertisement

First H a n d Brand & Flavor: An Experimental Investigation by Dan Maynes-Aminzade C ompanies spend a fortune making their logos ubiquitous, branding them into our consciousness. Is this money well spent? How much do a product’s brand and packaging affect our perceptions of what lies within? Consider wine and distilled spirits, a product arena in which luxury brands cost several orders of magnitude more than their generic counterparts. My curiosity about the effect of brand on perception was piqued when I read of a technique whereby drinkers on a budget could reproduce the taste of expensive vodka. Some enterprising “scientists” reported that pouring cheap vodka through a Brita filtration pitcher achieved the smooth taste of a “top shelf” brand. I was intrigued—if this worked, the potential gains would be staggering. Instead of wasting my money on Chopin or Grey Goose, I could purchase a $9 plastic handle of Vladimir vodka, run it though a filter, and mix up deliciously smooth martinis at a fraction of the cost. My enthusiasm for the method waned when I saw the suspicious methods used to evaluate it. The experimenters began by tasting the cheap vodka, which they agreed was horrible. They filtered it once and drank some more. Naturally, the vodka continued to taste better with 16 Ambidextrous Sizzling Summer 2007 each pass through the filter. In true scientific spirit, I decided to replicate the vodka filtration study under more controlled conditions. I started with two vodka varieties: Pavlova, a foul-smelling but extraordinarily inexpensive vodka ($8 per liter), and Ketel One, a Dutch vodka that is generally very highly regarded ($27 per liter). Subjects completed two doubleblind taste tests: one comparing filtered and unfiltered versions of Pavlova, and one comparing unfiltered Pavlova to Ketel One. I came to two conclusions. The first was rather disappointing: charcoal filtration does not result in a significant improvement in taste. Twelve tasters preferred the filtered during the filtration process. My experiment’s second conclusion was more surprising: most of the tasters couldn’t tell the difference between cheap and expensive vodka. Twelve subjects preferred Ketel One, eleven preferred Pavlova, and one had no opinion. I myself preferred the Ketel One; I wasn’t sure whether to be pleased with my refined taste in vodka or disappointed that I couldn’t reduce my monthly martini budget. Since taste preferences were split between the cheap and expensive brands, shall we conclude that buying “top shelf” vodka is a waste of money? Not necessarily. Blind taste tests conducted in a lab fail to take into account the preconditioning Our perception of a product’s quality is often influenced by external factors like its packaging and brand, which transfer into what we perceive as our direct perception alone. vodka, eleven preferred it unfiltered, and one had no opinion. Using a hydrometer, I measured the alcohol concentration of the vodka and found that while the unfiltered vodka was 82 proof, the filtered vodka was only 78 proof. Hence the slight preference for filtered vodka is probably due to the fact that some alcohol evaporates that normally goes into our gustatory judgments. When sampling vodka, we make a series of unconscious assessments based not only on the sensations from our taste buds and nostrils, but also on other sensory experiences. All of these combine into one general impression, which may not be strictly accurate. Marketing with Vodka Subjects failed to detect this: seven of the twelve tasters preferred vodka from the Absolut bottle, four preferred vodka from the Popov bottle, and one had no preference. Furthermore, they had strong opinions about their preferences, and some participants even had elaborate justifications: “Absolut’s flavor is more subtle and refined,” said one taster, “while Popov’s bluntness resembles rubbing alcohol.” “They start out the same,” explained another taster, “but Absolut has a smoother finish.” I am forced to conclude that the optimal strategy is to buy an expensive, top-shelf brand of vodka… once. Drink it yourself, save the empty bottle, and refill it with a cheaper and less-respected brand. If you get caught, tell your friends that you were simply trying to use sensation transference to improve their cocktail party experience. Photo by Malte Jung pioneer Louis Cheskin described this concept as sensation transference: our perception of a product’s quality is often influenced by external factors like its packaging and brand, which transfer into what we perceive as our direct perception alone. Since I was about to throw a party, I needed to know whether buying an expensive brand of vodka was worthwhile. I decided to conduct a second experiment examining how much our preconception of a brand’s quality affects its perceived taste. I began with two varieties of vodka: the mid-priced Swedish vodka Absolut, and Popov, a vodka manufactured in Ohio that can be acquired for less than one third of Absolut’s price. Absolut comes in an elegant, frosted glass bottle with a metal seal; the shape of this bottle has become legendary thanks to an ingenious advertising campaign spanning several decades. Popov comes in an oversize, ridged plastic bottle with a simple red-and-black sticker. My second test was not blind; the bottles were displayed prominently. I told tasters which vodkas they were sampling and asked for their preference. Unbeknownst to them, I had secretly filled both bottles with Popov, so they were always drinking the same vodka. Sizzling Summer 2007 Ambidextrous 17