ARTICLE IN PRESS

Journal of Environmental Psychology 26 (2006) 187–201

www.elsevier.com/locate/yjevp

Homeward bound: Introducing a four-domain model of perceived

housing in very old age

Frank Oswalda,, Oliver Schillinga, Hans-Werner Wahla, Agneta Fängeb,

Judith Sixsmithc, Susanne Iwarssond

a

Department of Psychological Ageing Research, Institute of Psychology, University of Heidelberg, Germany

b

Division of Occupational Therapy, Lund University, Sweden

c

Division of Psychology and Social Change, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK

d

Division of Gerontology and Caring Sciences, Lund University, Sweden

Abstract

The aim of this article is to introduce an integrative and more comprehensive approach to understanding and measuring perceived

housing in old age. First, four conceptual domains of subjective housing were introduced, based on the assumption that each of the

domains brings a unique perspective to the understanding of perceived housing: housing satisfaction, usability in the home, meaning of

home and housing-related control beliefs. Second, relationships between the proposed domains were empirically examined using

correlative analysis, factor analysis and structural equation modelling (SEM) techniques. Cross-cultural similarities and differences in the

observed empirical relations were then analysed across three Western European countries. Data were drawn from a sub-sample of the

participants in the European ENABLE-AGE Project amounting to 1223 old adults aged 80–89 years and living alone in their private

homes in Swedish, British, and German urban regions. The ENABLE-AGE data set has the advantage of containing measures related to

all four domains of perceived housing which are the focus of this paper. The results of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis as

well as of the SEM give empirical support for the usefulness of the theoretically proposed four component model of perceived housing.

Furthermore, multi-group analysis supports the assumption of similarity of perceived housing among older people living in the different

countries.

r 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

The vast majority of older adults live in ordinary

community-based dwellings. Among them, increasing

proportions of older people live alone, especially in the

rapidly growing population of the very old (i.e. 80 years of

age or more) (United Nations Development Programme,

2001). Typically, housing is treated as an important

objective context of ageing in the environmental-gerontology literature (e.g. Wahl, 2001; Wahl & Gitlin, 2006). One

major argument in this respect is that the immediate home

environment is the person’s major living space in old and

particularly very old age, both in terms of the increased

time older people spend at home, as well as the many

Corresponding author. Tel.: +49 6221 548114; fax: +49 6221 548112.

E-mail address: frank.oswald@psychologie.uni-heidelberg.de

(F. Oswald).

0272-4944/$ - see front matter r 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2006.07.002

activities that take place inside the home (Baltes, Maas,

Wilms, Borchelt, & Little, 1999).

Also, there is a strong relationship between age-related

loss in functional capacity, such as vision loss or mobility

impairment, and objective living arrangements. It has been

argued in the environmental press-competence model,

suggested by Lawton and Nahemow (1973), that elderly

people with pronounced functional loss are particularly

vulnerable to environmental challenges such as barriers

within the house or objective distance between the house

and important environmental facilities such as shops,

public transportation stops or park areas (see also Wahl,

Oswald, & Zimprich, 1999). Thus, the home may

compensate for the reduced functional capacity of the

ageing individual, i.e. after the implementation of barrierfree design and a full range of available housing adaptations (Gitlin, 1998). However, although of fundamental

importance, targeting only objective person-environment

ARTICLE IN PRESS

188

F. Oswald et al. / Journal of Environmental Psychology 26 (2006) 187–201

relations in this context presents a limited perspective on

housing in old age due to its neglect of the symbolic and

experiential dimension of ageing in place (Altman & Low,

1992; Rowles & Chaudhury, 2005; Wahl, Scheidt, &

Windley, 2004). In particular, a high degree of residential

stability in old age reflects an accumulation of home

experience over time. Housing contributes to everyday life

at home in terms of functional links related to behavioural

adaptation as well as in terms of meaningful links related to

identity (Oswald & Wahl, 2005; Rowles, Oswald, &

Hunter, 2004). Over time, a sense of ‘‘dwelling’’ or ‘‘being

in place’’ tends to develop as an expression not only of

habitual routines and cognitive awareness of interior home

spaces but also as a result of a psychological fusion of

person and place at home (Rowles et al., 2004; Sixsmith &

Sixsmith, 1991). In the rest of this article, we use the term

perceived housing to address the totality of subjective

phenomena of experiences and symbolic representations

related to living at home.

Over the years, a number of disciplines have contributed

to the understanding of perceived housing in old age such

as social geography (Rowles & Watkins, 2003), architecture (Després, 1991), anthropology (Miller, 2001; Rubinstein & De Medeiros, 2004), sociology (Mathes, 1978),

occupational therapy (Fänge & Iwarsson, 1999, 2003)

environmental psychology (Hay, 1998; Hayward, 1975;

Manzo, 2003, 2005; Moore, 2000; Sixsmith, 1986; Sommerville, 1997), and environmental gerontology (Oswald &

Wahl, 2005). As a consequence of this, a huge variety of

concepts and terms have been suggested to address

perceived housing. Among these are housing satisfaction,

experience of home, meaning of home, place attachment,

place identity, subjective housing, perceived environmental

control, and usability. One key problem in the literature

dealing with housing is that these concepts are often used

either interchangeably or in a rather isolated manner,

perhaps due to their diverse disciplinary origins. For

example, housing satisfaction has predominantly been

used in the psychology and sociology of ageing in place

(Pinquart & Burmedi, 2004), while place attachment has

been used in the anthropology of ageing (Rubinstein &

Parmelee, 1992) and issues of usability in occupational

therapy (Fänge & Iwarsson, 2003, 2005a, 2005b). Given the

heterogeneity of these constructs, there is a clear need for

an integrative approach which identifies the role of such

concepts in comprehensively documenting the subjective

perception of home in old age.

Furthermore, perceived housing is linked to the existing

sociocultural background (e.g. Rubinstein & De Medeiros,

2004). However, cultural differences in this regard are often

addressed in terms of developmental contexts in early life

or as extremes due to climate, religious background, daily

habits, and economics, e.g. in so-called ‘‘Third World’’

versus ‘‘First World’’ nations (e.g. Hay, 1998; Miller,

2001). Beyond such contrasts, cross-national housingrelated research with older adults has remained quite

rare.

The overall objective of this article is to propose an

integrative and more comprehensive approach to better

understand perceived housing in old age on the conceptual

and empirical level. In terms of the conceptual level, we

argue for the need to consider a family of four domains as a

best available representation of perceived housing: housing

satisfaction, usability in the home, meaning of home, and

housing-related control beliefs. Regarding the empirical

level, we analyse the relationships of the four domains

based on the assumption that each of the domains brings a

unique perspective to the understanding of perceived

housing. In addition, the question of cross-country

usefulness of the four component model will be addressed

by drawing from comparative data available from three

European countries (Germany, Sweden, and the UK). We

start with a case example derived from the same data set

(i.e. the ENABLE-AGE Project) to illustrate the complex

ways in which housing is perceived by older people, then

proceed with a conceptual analysis of perceived housing,

followed by the presentation of respective empirical

findings.

1.1. On the complexity of perceived housing: a case example

Mrs. Scott is 89 years old and living alone in a village

setting in the North West of England. She owns her own

detached bungalow with gardens to front and rear,

abutting a golf course. Over the past 2 years, Mrs. Scott

has become increasing more frail and immobile and at the

time of interview, was suffering from pain in her hips (she

has already experienced three hip operations) and legs,

accompanied by heart, lung and urinary problems. In

addition, she complains of eye and hearing impairments

and general fatigue. In constant pain and with debilitating

symptoms, Mrs. Scott was in remarkably good mental

health, she said, enjoying her life and taking part in social

events with family and friends. For her, home was the

centre of family life, the place her sister (aged 91), her own

children and grandchildren treat as the focus of family life.

Her home is not simply a current lived experience, but a

storehouse of memories and the incarnation of her whole

life lived in this familiar space with her now deceased

husband and young children. Their presence was still felt in

the fabric, the furnishings, the layout and the memorabilia

surrounding her, making this house her home. Mrs Scott

thinks of her home as the centre of her social community,

where friends and neighbours visit, play bridge and gossip.

As she said, ‘‘In my home, the world comes to me!’’.

Home for Mrs. Scott should be a tidy, clean place

offering comfort, privacy and security. However, her health

problems have resulted in her inability to maintain her

home as she had previously done, and to remain

independent, Mrs. Scott required a substantial amount of

domestic and personal care. This meant that her home was

no longer the private refuge it had been in the past, as

carers and helpers woke her up, put her to bed, bathed her,

cooked, cleaned and tidied the house. Interestingly,

ARTICLE IN PRESS

F. Oswald et al. / Journal of Environmental Psychology 26 (2006) 187–201

although she had relinquished control of her body and her

home in these respects to paid ‘strangers’, she still felt in

psychological control over her environment, after all, it

was she who gave instructions about when and how to

manage the home. Despite such control, safety and security

were problematic for Mrs. Scott as she feared the

consequences of burglary and falls. Subsequently, she

had reorganized her immediate living space to contain

all she needed on a daily basis, centralizing her life

around her favourite chair within her living room.

From here, she looks out onto her back garden and the

adjoining golf course and waves to the golfers passing by,

unable to get out to chat to them due to the raised

threshold separating garden from home. This she said,

created a huge barrier for her, cutting her off from the

pastimes she loves, gardening and chatting, and effectively

holding her prisoner inside her own home: a home she

does not want to leave despite her frailty because to do so

would not simply be leaving a house but, ‘‘ysplitting up a

family’’.

This case study indicates that Mrs. Scott’s home cannot

be described simply by attitudinal housing satisfaction, but

covers usability to maintain her daily habits and routines.

Moreover it spans the full scope of cognitive, emotional,

behavioural, physical and social meanings as well as being

important in terms of perceived control over the environment. In sum, understanding of the psycho-social home

requires the integration of satisfaction, meaning of home,

usability and housing-related control.

1.2. Description of four domains of perceived housing

1.2.1. Housing satisfaction

Housing satisfaction is the classic measurement of

perceived housing and used in many studies around the

globe since the 1960s (e.g. Aragonés, Francescato, &

Gärling, 2002; Pinquart & Burmedi, 2004). The potential of

the construct of housing satisfaction lies in its ambition to

provide a broad and simple overall attitudinal and mostly

cognitive evaluation of housing (Hidalgo & Hernadez,

2001). Housing satisfaction is a well-established construct

in assessing the perceived quality of the home (e.g. for a

summary see Aragonés et al., 2002; Hidalgo & Hernadez,

2001; Weidemann & Anderson, 1985). However, there is

neither a generally accepted definition nor a generally

acknowledged methodological standard to measure housing satisfaction, although in survey research single item

measures are used quite frequently (Pinquart & Burmedi,

2004). Research has repeatedly revealed that housing

satisfaction could also be understood as a complex

outcome of demographic and health-related circumstances

as well as objective and subjective characteristics of the

person’s environment (e.g. Christensen, Carp, Cranz, &

Whiley, 1992; Heywood, Oldman, & Means, 2002; Jirovec,

Jirovec, & Bosse, 1984). A meta-analysis has revealed that

the association between residential conditions and residential satisfaction is stronger in younger than in older

189

samples, indicating that old people base their satisfaction

evaluation less strongly on objective characteristics (Pinquart & Burmedi, 2004). Indeed, high levels of housing

satisfaction among older people have frequently been

reported in objectively poor living arrangements, labelled

as the housing satisfaction paradox (Kivett, 1988; Staudinger, 2000; Walden, 1998). Older people seem to be

particularly adept at adapting to different objective living

conditions and sustaining high levels of satisfaction

(Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999; Schwarz & Strack,

1991; Staudinger, 2000).

In conclusion, housing satisfaction is a common and

important indicator to measure perceived housing (e.g.

Heywood et al., 2002). The construct is, however, limited

with respect to the understanding of home because it

provides only a global and predominantly cognitive

evaluation of the relation of the ageing person to her/his

home environment (Pinquart & Burmedi, 2004; Staudinger,

2000). To contain the scope of housing satisfaction in the

current study, we focus entirely on satisfaction with

physical housing conditions.

1.2.2. Usability in the home

Usability in the home is a construct predominantly

developed within occupational therapy research since end

of the 1990s (e.g. Fänge & Iwarsson, 2003; Iwarsson &

Ståhl, 2003). Its major focus is on activity and functionality, addressing perceived possibilities to perform necessary and preferred activities in a given home environment

(Fänge & Iwarsson, 2005a, 2005b). Usability has been

defined as the extent to which the person’s housing needs

and preferences can be fulfilled in terms of activity

performance at home (Fänge & Iwarsson, 2005a), comprising a personal component, an environmental component,

and an activity component. The personal component

relates to functional capacity, adaptive strategies, and

motivation, while the environmental component relates to

the physical environmental barriers in the home and its

close surroundings. Finally, the activity component relates

to the personal repertoire of activities in the home (Fänge

& Iwarsson, 2005a, 2005b; Iwarsson & Ståhl, 2003), and

their characteristics (Fänge & Iwarsson, 2005a). Usability

is based on core assumptions underlying occupational

therapy theory, i.e. person–environment–activity transactions (Fänge & Iwarsson, 2003, 2005a; Law et al., 1996), as

well as on Lawton’s ecological model (Lawton & Nahemow, 1973). Empirical studies have focused on the

relationship between housing accessibility and usability

(Fänge & Iwarsson, 2003), as well as longitudinal changes

along housing adaptation processes (Fänge & Iwarsson,

2005a, 2005b).

In conclusion, usability adds to the understanding of

perceived housing mainly by considering the perceived

usefulness of the home environment for everyday activities.

In this way, and very similar to the limits of the concept of

housing satisfaction, it provides only a partial understanding of perceived housing.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

190

F. Oswald et al. / Journal of Environmental Psychology 26 (2006) 187–201

1.2.3. Meaning of home

The concept of meaning of home refers to a body of

work which has grown since the end of the 1970s based on

the work from Hayward (1975), Relph (1976), Rowles

(1978) and others. Studies framed within anthropology

(e.g. Rubinstein & De Medeiros, 2004), social geography

(Rowles, 1983), and psychology (e.g. Hayward, 1975;

Manzo, 2003, 2005; Moore, 2000; Oswald & Wahl, 2005)

have contributed to phenomena concerned with symbolic

representations of space and place and personal meanings

linked to one’s home. Based on theories of place identity

(e.g. Proshansky, Fabian, & Kaminoff, 1983; Stedman,

2002), the home is not only considered to fulfil objective

functions (e.g. shelter, support, access, use), but represents

individual meanings related to the inhabitant’s experience

and personality. The concept of meaning of home is used to

cover subjectively meaningful habits, social contacts,

evaluations, goals, values, cognitions and emotions of a

person in relation to their home (Manzo, 2005; Marcus,

1995; Moore, 2000; Oswald & Wahl, 2005; Sixsmith, 1986).

The meaning of home describes the accumulation of a

range of place attachment processes, operating when

people form affective, cognitive, behavioural and social

bonds to a particular setting (Brown & Perkins, 1992),

thereby transforming space into place (Altman & Low,

1992; Rowles & Watkins, 2003). In contrast to housing

satisfaction, meaning of home is not only related to

evaluative components of the home. Rather, behavioural

aspects of meaning can reflect familiarity and routines

developed over time, and cognitive, emotional and social

aspects of meaning are manifest through processes of

reflecting on the past, symbolically represented in certain

places and cherished objects.

Moreover, the need to cope with impairments in old age

can be linked to specific meaning patterns. A study with

mobility impaired and blind elders revealed different

meanings in regard to physical, behavioural, cognitive,

emotional and social aspects (Oswald & Wahl, 2005). Such

experiential differences support the notion that individual

meaning may serve as a resource to cope with everyday

problems but also that the home may become a potentially

problematic space, an environment of stress and distress

(Sixsmith & Sixsmith, 1991).

In conclusion, the concept of meaning of home covers a

broad scope of evaluations related to the home environment,

represented subjectively within the individual. However, there

are still other components relevant for perceived housing,

which are not covered by the concepts of housing satisfaction,

usability or meaning of home. In particular, we argue that

control beliefs in the domain of housing provide a fourth class

of processes to be integrated in our model of perceived

housing (e.g. Slangen-de Kort, 1999).

ceived control in different domains of life (Lachman, 1986;

Lachman & Burack, 1993; Levenson, 1973, 1981). Given

that striving for control has advantages for all species

capable of influencing their environment (Schulz &

Heckhausen, 1999), control beliefs have been found to

reflect a major driving force in explaining the course and

outcome of ageing (Heckhausen & Schulz, 1995; Levenson,

1973; Smith, Marsiske, & Maier, 1996). Psychological

control theory has recently also been applied to the housing

domain (Oswald, Wahl, Martin, & Mollenkopf, 2003a,

2003b). Housing-related control beliefs explain events at

home either as contingent upon one’s own behaviour, or

upon luck, chance, fate, and powerful others. Here, the

major argument is that control beliefs related to the

regulation of person–environment interchange at home

becomes increasingly important in very old age. Striving

for housing-related control has also been shown to be

linked to the maintenance of independence in daily living

and well-being in very old age (Oswald et al., 2003a,

2003b). Furthermore, housing-related control beliefs can

be expected to trigger residential decisions such as ‘staying

put’ versus moving to sheltered housing or institutional

settings. In conclusion, we argue that control beliefs in

relation to housing add a unique and innovative aspect to

the concept of perceived housing.

1.2.4. Housing-related control beliefs

This strand of research to be considered within any

integrative and comprehensive model of perceived home

derives from psychological theories and studies on per-

3.1. Project context

2. Empirical research objective and hypothesis

Our theoretical contention is that all four domains—

housing satisfaction, usability, meaning of home, and

housing-related control beliefs—should be simultaneously

considered for a more comprehensive understanding and

holistic empirical analysis of perceived housing. Concerning the four domains of perceived housing, we strove to

analyse empirical relations between indicators representing

these domains, in order to detect to what extent these four

domains overlap or differ in content.

We hypothesized that the domains of housing satisfaction, meaning of home, usability in the home, and

perceived housing-related control cover distinct dimensions

of housing evaluation. Applying a combination of exploratory and confirmatory data analytic procedures, we

expected to find a four-factor solution which supports the

distinctiveness of the four conceptual domains.

Furthermore, we explored whether comparable relationships between the constructs do exist in all three European

sub-samples selected for this study (Germany, Sweden, and

the UK), indicating universality of perceived housing and

by this also the cross-country usefulness of our conceptual

proposal and its empirical validity.

3. Method

This study is based on data collected for an extensive

European research project, the ENABLE-AGE Project

ARTICLE IN PRESS

F. Oswald et al. / Journal of Environmental Psychology 26 (2006) 187–201

(Iwarsson, Nygren, & Slaug, 2005; Iwarsson, Wahl, &

Nygren, 2004). The overarching aim of the project was to

explore the home environment as a determinant for healthy

ageing in very old age using a longitudinal perspective in

five countries (Germany, Sweden, the UK, Hungary, and

Latvia). The project comprised three major parts. First, a

macro level update on housing policies was conducted.

Second, a longitudinal survey comprising two measurement points (N ¼ 1918) took place (ENABLE-AGE

Survey Study) and third, an in-depth study based on

interviews and case study analyses was completed (ENABLE-AGE In-depth Study). The data used in this article

derived from the ENABLE-AGE Survey Study with its

rather comprehensive focus on perceived housing, supported by a case example derived from the ENABLE-AGE

In-depth Study.

3.2. Sample

For this study, data were drawn from the Swedish,

British, and German sub-samples of the data set, for two

reasons. First, the target sample in each country was

comparable in terms of the age-range, i.e. 80–89-year-old

adults living in single-person private households in

urban districts (about 75% women), whereas in both

East-European countries the age range was 5 years

younger due to different life expectancy rates (Iwarsson

et al., 2004). Second, we decided to emphasize in this

first stage of analyses those countries which have

been members of the European Union for many years,

assuming a considerable amount of comparability in

societal infrastructure and housing standards for older

adults. In all, the sample used for this study comprised

N ¼ 1223 80–89-year-old adults, who took part in the first

measurement point of the ENABLE-AGE Survey Study

(see Table 1).

As shown in Table 1, differences in education and

objective finances existed in the three countries, although it

should be noted that subjective evaluations of financial

resources were comparable in all three research sites.

Although there were also differences in subjective health

191

and duration of living, this nevertheless was a relatively

fragile sample of very old adults who on average had lived

in their current homes over a long time period.

3.3. Data collection procedure

All instruments used in the survey were administered in

individual face-to-face sessions at home visits. The instruments and project-specific questions were translated and

back translated into the different languages of the

participating countries, followed by pilot examinations

and bi-lingual final language adjustments. Involving

researchers and interviewers from all participating countries, a series of 3-day interviewer courses were held,

focusing on reliable administration of all instruments

involved (Iwarsson et al., 2005). Next, in each country

the national project leader arranged team courses, instructing and training all interviewers in their own language and

context.

In Sweden and Germany, participants were randomly

sampled from official registers in urban regions. Intended

participants were consecutively included from sampling

lists, via mailed letters followed by phone calls using a

project-specific sampling strategy with well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Iwarsson et al., 2005). All

participants were enrolled after informed consent had been

given, following the ethical guidelines and procedures for

formal ethical consent of each country. In the UK, where

official urban registers are not made available to researchers in the way necessary for the ENABLE-AGE Project,

participants were sampled through (Primary Care Trust)

PCT lists followed by invitation letters. Since communitydwelling very old persons who live alone are considered to

be very sensitive and vulnerable concerning extensive

external contact with researchers, as expected the refusal

rates were considerable (58.9% in Sweden, 67.2% in

Germany; no information available in the UK due to

ethical considerations). However, the most important

reasons for refusal were comparable in all three countries,

such as ‘‘lack of interest or time’’, ‘‘poor health’’, and

‘‘interview too stressful’’.

Table 1

Sample description

p

(N ¼ 1223)

(M, S.D.) or (%, n)

Sweden

(n ¼ 397)

Germany

(n ¼ 450)

UK

(n ¼ 376)

Age (years)

Gender (% women)

Education (years of schooling)

Finances (h per month and person)a

Subjective evaluation of finances

(% rating income as ‘‘high’’)

Subjective health (satisfaction 1–5)b

Duration of living in same home (years)

84.6 (3.1)

74.6%

8.8 (2.2)

1015

85.1 (3.2)

78.4%

11.6 (2.6)

1569

84.8 (2.7)

70.0%

9.9 (1.9)

1044

***

***

10.6% (42)

3.6 (0.8)

21.8 (17.4)

9.1% (41)

2.8 (1.1)

33.5 (19.4)

10.9% (41)

3.0 (1.0)

25.0 (18.3)

n.s.

***

***

Note: Statistical test for differences: F-test (means), Chi-Square-test (frequencies) with not significant: n.s., po:05 ; po:01 ; po:001 .

a

In Germany 122 participants, in Sweden 54, in the UK 68 participants refused to give information.

b

Subjective evaluation, higher scores indicate lower subjective health (SF 36).

ARTICLE IN PRESS

192

F. Oswald et al. / Journal of Environmental Psychology 26 (2006) 187–201

3.4. Instruments

3.4.1. Housing satisfaction

To measure housing satisfaction (HSAT) a single item

measure was used which specifically targeted satisfaction

with the condition of the house (‘‘Are you happy with the

condition of your home?’’). This item was drawn from the

more extensive Housing Options for Older People (HOOP)

questionnaire (Heywood et al., 2002). The question on

housing conditions was answered on a five point scale from

1 ¼ ‘‘definitely not’’ to 5 ¼ ‘‘yes, definitely’’, adapted from

the original questionnaire (Sixsmith & Sixsmith, 2002). In

the English assessment battery the notion of satisfaction

was represented by the word ‘‘happy’’ to remain close to

normal everyday language used by older people as

identified in the ENABLE-AGE qualitative pilot studies.

Indeed, the wording of this question varied slightly in each

of the participating countries to reflect common language

usage around issues of housing satisfaction. In Sweden this

was translated most effectively in terms of ‘‘feeling

content’’ and in Germany, the term equivalent to

‘‘satisfied’’ was used. The English items of all questionnaires (as well as M, S.D., and range) are listed in Table 2

(see Table 2).

3.4.2. Usability in the home

In order to capture usability, the Usability in My Home

Questionnaire (UIMH) (Fänge & Iwarsson, 1999, 2003,

2005a, 2005b) was applied. This instrument addresses the

degree to which the physical housing environment supports

the performance of activities at home, based on individual

subjective judgements. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale

from 0 ¼ ‘‘not at all’’ to 5 ¼ ‘‘fully agree’’ (see Table 2).

The items of the instrument have been found in earlier

research to reveal to a three-factor pattern (Fänge &

Iwarsson, 2003) addressing activity aspects, personal and

social aspects, and physical environmental aspects of

usability. Psychometric analyses in the present data set,

however, indicated a limited level of internal consistency

(Cronbach’s ao0:50) in the ‘‘personal and social aspects’’

sub-scale. Thus, only two sub-scales were used in the

current study: ‘‘Activity aspects’’ (UMH1: 4 items, sumscore; Cronbach’s a ¼ 0:67) and ‘‘Physical environmental

aspects’’ (UMH2: 6 items, sum-score; a ¼ 0:75).

3.4.3. Meaning of home

To measure meaning of home, we used the Meaning of

Home Questionnaire (MOH) which was developed to

assess older individual’s subjective meanings in four areas

of particularly theoretical importance: physical, behavioural, cognitive/emotional and social (Oswald et al., 1999).

Participants were instructed to judge to what extent they

personally agreed or disagreed with the statements on an

11-point scale from 0 ¼ ‘‘strongly disagree’’ to

10 ¼ ‘‘strongly agree’’ (see Table 2). The development of

the scale covered open-ended examinations of a broad

scope of contents for each domain (for details see Oswald

& Wahl, 2005), purposefully selected to represent pronounced heterogeneity of perceived housing. Psychometric

analyses in the present data set indicated acceptable

internal consistency (Cronbach’s a40:50) in three out of

four sub-scales, that is physical aspects (MOH1: seven

items, a ¼ 0:60), behavioural aspects (MOH2: six items,

a ¼ 0:67), and cognitive/emotional aspects (MOH3: 10

items, a ¼ 0:62). The sub-scale on social aspects (five items,

a ¼ 0:44) was discarded due to its low reliability.

3.4.4. Housing-related control beliefs

Housing-related control beliefs were assessed with the

Housing-related Control Beliefs Questionnaire (HCQ).

This scale was developed as a 24-item questionnaire, based

on the widely used psychological dimensions of Internal

Control (8 items, sum-score), External Control: Powerful

Others (8 items, sum-score), and External Control: Chance

(8 items, sum-score) (Oswald et al., 2003a, 2003b).

Participants were instructed to judge to what extent they

personally agree or disagree with the statements on a fivepoint scale from 1 ¼ ‘‘not at all’’ to 5 ¼ ‘‘very much’’ (see

Table 2). ‘‘Internal Control’’ means that housing-related

events are highly contingent upon a person’s own behaviour,

where personal responsibility implies that one is responsible

for what happens. ‘‘External Control’’ means either some

other person is responsible or things happen by mere luck, by

chance, or by fate. However, psychometric analyses in the

present data set indicated poor levels of internal consistency

in the internal control sub-scale and only medium internal

consistency in both external control sub-scales. To improve

the psychometric qualities of this instrument in the current

analysis, the internal control sub-scale was removed. The

removal of the internal control sub-scale was in accordance

with the conceptual argument that housing-related external

control is of particular interest in perceived housing in very

old age (e.g. Baltes, Freund, & Horgas, 1999). Further, both

external sub-scales were combined, resulting in sufficient

reliability (HEXC: 16 items, a ¼ 0:67).

3.5. Data analysis

Descriptive results are based on bi-variate correlative

findings. To acknowledge the large sample, correlation

coefficients are reported only with po0:001. Regarding the

effect sizes of correlation coefficients, data analyses will

follow Cohen’s proposal (1988), arguing that rX0.1 is

considered as a ‘‘small effect’’, r from 0.3 to 0.5 as a

‘‘medium effect’’, and rX0.5 as a ‘‘large effect’’.

To test for the empirical dimensionality of the set of

instruments, we chose an exploratory factor analysis

approach using principal component analysis. The benefit

of exploratory factor analysis is the ‘‘unconditional’’

examination of the factorial structure, enabling detection

of factors not hypothesized a priori. With respect to the

exploratory analysis, we expect from our hypothesis that a

four factor solution—revealing the four domains as basic

factors—could be accepted from the results.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

F. Oswald et al. / Journal of Environmental Psychology 26 (2006) 187–201

193

Table 2

Instruments on perceived housing in old age

Remaining items of questionnaires on perceived housing (numbers in order of presentation in

the questionnaire)

Housing satisfaction (Sixsmith & Sixsmith, 2002)

Housing satisfaction (1 item)

1. Are you happy with the condition of your home?

Usability in my home (Fänge & Iwarsson,1999)

Usability in my home: activity aspects (4 items)

1. In terms of how you normally manage your personal hygiene, dressing, visiting the toilet, or

how you eat, to what extent is the home environment suitably designed in relation to this?

2. In terms of how you normally manage your cooking/heating of food or preparation of

snacks, to what extent is the home environment suitably designed in relation to this?

3. In terms of how you normally manage your washing up, cleaning, care of flowers, to what

extent is the home environment suitably designed in relation this?

4. To what extent is the home environment suitably designed in relation to how you normally

manage your washing, ironing, mangling, or repair of clothes?

Usability in my home: physical environmental aspects (6 items)

10. How usable do you feel that your home environment is in general?

11. How usable do you feel that the environment outside your home is?

12. How usable do you feel that the entrance to your home is?

13. How usable do you feel that the secondary spaces in your home are?

15. How usable do you feel that the balcony, patio, or garden is?

16. How usable do you feel that the interior of your home is?

Meaning of home (Oswald, Mollenkopf, & Wahl, 1999)

Meaning of home: physical aspects (‘‘Being at home means for mey’’) (7 items)

1. Living in a place which is well-designed and geared to my needs

6. Having to live in poor housing conditions [item value was reversed for calculations]

7. Having a nice view

12. Living in a place that is comfortable and tastefully furnished

15. Feeling that the home has become a burden [item value was reversed for calculations]

20. Having a base from which I can pursue activities

25. Being confined to the rooms (and things) inside the home [item value was reversed for

calculations]

Meaning of home: behavioural aspects (‘‘Being at home means for mey’’) (6 items)

2. Managing things without the help of others

8. Doing everyday tasks (e.g. housework)

13. Being able to change or rearrange things as I please

16. Not having to accommodate anyone’s wishes but my own

21. No longer being able to keep up with the demands of my home (e.g. maintenance) [item

value was reversed]

26. Being able to do whatever I please

Meaning of home: cognitive/emotional aspects (‘‘Being at home means for mey’’) (10 items)

3. Being familiar with my immediate surroundings

4. Feeling safe

9. Being bored [item value was reversed for calculations]

10. Knowing my home like the back of my hand

14. Being able to relax

17. Thinking about the past (e.g., important persons and events)

18. Enjoying my privacy and being undisturbed

22. Thinking about what living here will be like in the future

23. Feeling comfortable and cosy

27. Feeling lonely [item value was reversed for calculations]

Housing-related control beliefs (Oswald et al., 2003)

Housing-related control beliefs: external control (16 items)

2. I rely to a great extent upon the advice of others when it comes to helpful improvements to

my home

3. Having a nice place is all luck. You cannot influence it; you just have to accept it

5. Whether or not I will be able to stay in my home will probably depend on other people

6. It’s purely a matter of luck whether or not neighbours will step in if I need help

8. In order to do anything interesting outside of my home I have to rely on others

9. Whether or not I can stay in my home depends on luck and circumstance

11. I must rely on others when it comes to making use of support services and facilities in my

local area

12. You just have to live with the way your home is; you cannot do anything about it

Mean

S .D .

Range

4.62

0.77

1–5a

4.60

0.77

1–5b

4.58

0.90

1–5

4.46

1.10

1–5

3.98

1.70

1–5

4.63

4.31

4.44

4.25

4.13

4.70

0.72

1.02

0.92

1.10

1.49

0.62

1–5

1–5

1–5

1–5

1–5

1–5

9.15

9.57

7.94

9.24

8.98

8.55

7.58

1.69

1.57

2.80

1.58

2.18

2.62

3.72

0–10c

0–10

0–10

0–10

0–10

0–10

0–10

8.15

7.97

8.50

8.63

7.35

2.70

2.81

2.78

2.68

3.44

0–10

0–10

0–10

0–10

0–10

9.44

1.59

0–10

9.33

9.40

8.42

9.35

9.56

7.56

9.14

4.74

9.57

6.95

1.48

1.37

2.74

1.69

1.23

3.08

1.87

3.99

1.20

3.55

0–10

0–10

0–10

0–10

0–10

0–10

0–10

0–10

0–10

0–10

2.77

1.32

1–5d

2.44

2.79

2.65

2.69

3.71

2.43

1.29

1.35

1.31

1.47

1.28

1.37

1–5

1–5

1–5

1–5

1–5

1–5

2.94

1.48

1–5

ARTICLE IN PRESS

194

F. Oswald et al. / Journal of Environmental Psychology 26 (2006) 187–201

Table 2 (continued )

Remaining items of questionnaires on perceived housing (numbers in order of presentation in

the questionnaire)

Mean

S.D.

Range

14. When other people offer to help around the house or help me outside the home, I can’t say

no

15. Where and how I live has happened more by chance than anything else

17. Other people have told me how to arrange the furnishings in my home

18. It’s a case of luck or chance whether I will be able to continue my present way of life in my

home in the future

20. I listen to the advice of others when they tell me not to change anything in my own home

21. The way my home has been set up just happened by chance, over time

23. Other people are to blame if my home is not a place where I can enjoy life

24. Whether or not there are support services or community facilities in my neighbourhood is

just a matter of luck

2.97

1.46

1–5

2.84

1.73

3.59

1.52

0.98

1.27

1–5

1–5

1–5

2.45

3.17

1.78

3.09

1.28

1.45

1.01

1.37

1–5

1–5

1–5

1–5

a

From 1 ¼ ‘‘definitely not’’ to 5 ¼ ‘‘yes, definitely’’.

From 0 ¼ ‘‘not at all’’ to 5 ¼ ‘‘fully agree’’.

c

From 0 ¼ ‘‘strongly disagree’’ to 10 ¼ ‘‘strongly agree’’.

d

From 1 ¼ ‘‘not at all’’ to 5 ¼ ‘‘very much’’.

b

Next, to test the hypothetically proposed and empirically

revealed four factor model’s fit to the data, a confirmatory

factor analysis approach, indicating a structural equation

model (SEM), was considered to be the optimal strategy.

Confirmatory factor analysis offers the benefits of estimating how well the model fits the data and further analysing

structural relations between the latent factors specified.

With respect to confirmatory analysis, we expected good

model fit confirming the four factor model, with the latent

factors representing the four domains. As we expected

correlations between single indicators across domains, we

computed modification indices and included these singleindicator cross-domain correlations which showed a strong

impact on model fit. Evaluation of model fit was based on

the normed fit index (NFI), comparative fit index (CFI),

and root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA),

and we followed widely used ‘‘rules of thumb’’ for good

model fit, i.e. NFI and CFI40.9 and RMSEA o0.05 (for

discussion of SEM fit evaluation see Hu & Bentler, 1999;

Marsh, Balla, & Hau, 1996). We did not use the w2-test of

overall model fit due to the well-known problem of overrejection of true models due to large sample sizes.

To address potential cultural differences between the

different research sites in terms of structural relations, a

multi-group analysis was conducted (multi-sample SEM),

involving simultaneous estimation of sample-specific parameter values for the three sub-samples (e.g. Bollen, 1989).

Thus, this method allows for between-country differences

in the structural parameters (e.g. correlations between

latent factors), but also serves to test the goodness of fit of

the proposed factor structure across the different research

sites.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive findings on the bivariate level

In order to empirically reveal the relationships between

the selected domains of perceived housing, zero-order

correlations were found, as shown in Table 3 (see Table 3).

Basically, concerning the relation of different aspects of

perceived housing, high usability scores are linked with

high amounts of different aspects of meaning of home and

housing satisfaction. Moreover, usability and meaning

scores were negatively linked to external control beliefs.

That is, participants who consider their homes as useful for

daily activities have stronger meaningful links to their

homes, are more satisfied with their housing conditions and

think less often that others are responsible for what

happens in their homes.

The set of bivariate interrelations between subscales for

domains of perceived housing revealed statistically significant but low to medium correlations, indicating that the

measurement scales and domains were largely independent

of each other due to content specificity. Moreover, the

findings show that these domains were not completely

independent, i.e. they represent different facets of perceived

housing.

Highest correlations were found within the ‘‘Usability in

My Home’’ questionnaire between the scales for environmental and activity aspects (r ¼ 0:52) as well as within the

‘‘Meaning of Home’’ questionnaire sub-scales, especially

between the scales for physical and behavioural aspects of

meaning, (r ¼ 0:50) respectively. The findings further

revealed that concepts which are expected to be closely

related due to overlapping contents, especially activity

aspects of usability and behavioural aspects of meaning of

home (r ¼ 0:38), are linked to each other, whereas, for

instance, the global indicator of ‘‘Housing Satisfaction’’

and the remaining measures of perceived housing are

interrelated only weakly (ranging between 0.11 and

0.28). Finally, there were consistently negative (albeit

relatively weak) correlations between ‘‘Housing-related

External Control Beliefs’’ and other measures of perceived

housing (ro 0:25), indicating that believing events at

home are contingent upon external influences is higher

when perceived usability, meaning and satisfaction is

lower.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

F. Oswald et al. / Journal of Environmental Psychology 26 (2006) 187–201

4.2. Test of the central hypothesis: empirical distinctiveness

of the four domain model of perceived housing

To determine the underlying factor structure of perceived housing measured in this study, an exploratory

factor analysis was conducted with a slightly reduced

sample of N ¼ 1189 due to missing values. The factor

structure and factor loadings are shown in Table 4. Results

revealed one strong first factor (eigenvalue 2.66, explaining

38% of variance) and another three factors explaining

12–16% of the variance each (eigenvalues 1.13; 0.92; 0.81

resp.) whereas the remaining factors showed lower

proportions of variance explanation o8%. This can be

interpreted in terms of a four factor solution, explaining

79.0% of the variance, indicating that considerable

amounts of perceived housing can be explained by the

four domains of meaning, usability, external control beliefs

and satisfaction. The Varimax rotated pattern of factor

loadings shows all subscales addressing meaning of home

with highest loadings (all 40.72) on factor 1, both

subscales addressing usability in the home with highest

loadings (0.78, 0.87) on factor 2, while not substantially

loading on the other factors. Factor 3 is dominated by the

external control belief sum-score (0.98) and the housing

satisfaction single item score is exclusively loaded on factor

4 (0.96). Thus exploratory factor analysis revealed evidence

for a four factor solution such that the four domains of

perceived housing are distinct as expected hypothetically.

Notably, regarding the eigenvalues, the four factor solution

195

appeared to be the most suitable compared to all other

possible factor structures which might have been used for

further interpretation.

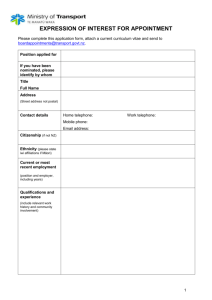

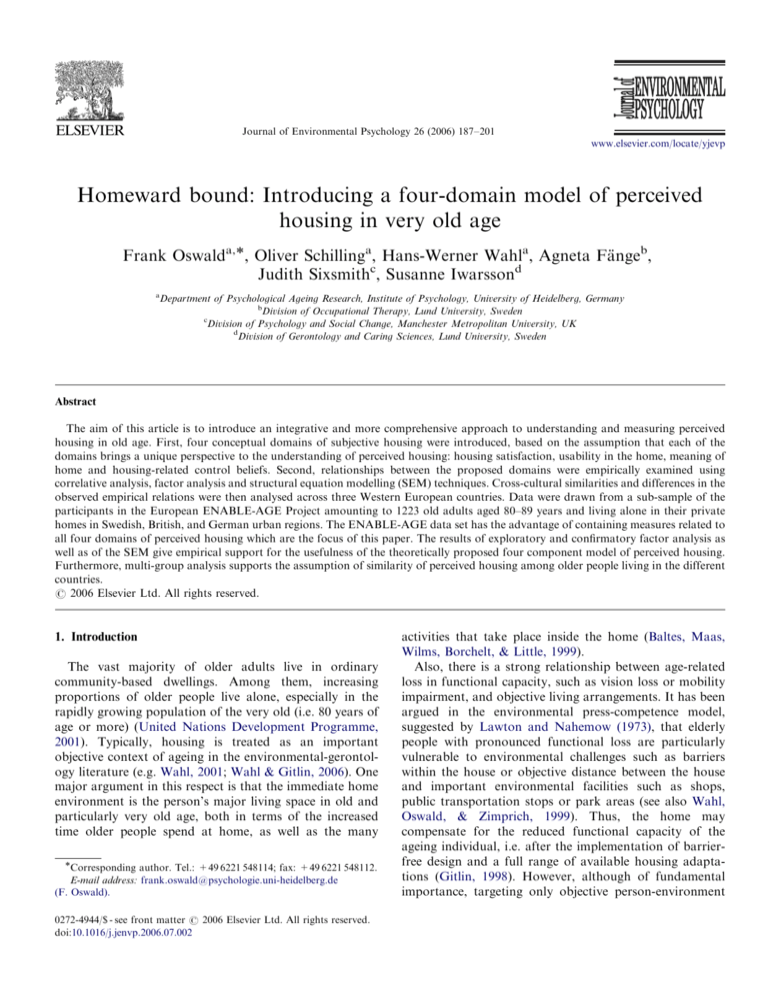

Results of the test of the four factor model’s fit to the

data are reported, based on a confirmatory factor analysis

approach. The findings are shown in Fig. 1, by indicating a

structural equation model (SEM) computation (see Fig. 1).

As there was only one observed indicator for housing

satisfaction (HSAT, single item) and external housing

related control beliefs (HEXC, sum-score), measurement

error variance had to be constrained to zero in order to

identify the model (i.e. observed scores are taken as error

free measures of the underlying true-score). The four

domains of perceived housing (in circles) were allowed to

correlate, as implied in the theoretical considerations made

above.

First, the SEM results revealed a ‘‘close to good’’ model

fit (RMSEA ¼ 0.055; NFI ¼ 0.914; CFI ¼ 0.931) (not in

the figure). Modification indices showed a correlation

between MOH2 (meaning of home: behavioural aspects)

and UMH1 (usability in the home: activity aspects) as

those leading to best fit improvement (for explanation of

modification indices, see Bollen, 1989). This cross-domain

correlation was in line with the theoretical considerations

and correlative findings on activity/behaviour-oriented

aspects of perceived housing. Allowing for just this

additional single-indicator correlation led to good model

fit with RMSEA ¼ 0.041 (90% confidence interval

0.031–0.052), NFI ¼ 0.948, CFI ¼ 0.964 (see Fig. 1)

Table 3

Interrelations between aspects of perceived housing in old age

Domains of perceived housing

HSAT

UMH1

UMH2

MOH1

MOH2

MOH3

Housing satisfaction (HSAT)

Usability in my home: activity aspects (UMH1)

Usability in my home: physical environmental aspects (UMH2)

Meaning of home: physical aspects (MOH1)

Meaning of home: behavioural aspects (MOH2)

Meaning of home: cognitive/emotional Aspects (MOH3)

Housing-related external control beliefs (HEXC)

1.00

0.17

0.28

0.26

0.13

0.11

0.11

1.00

0.52

0.26

0.38

0.16

0.25

1.00

0.34

0.34

0.18

0.23

1.00

0.50

0.44

0.19

1.00

0.43

0.19

1.00

n.s.

Note: Correlation coefficients p40:001; n.s. ¼ not significant.

Table 4

Exploratory factor structure of the set of instruments on perceived housing

(N ¼ 1189)

Factors and factor loading

Communality

Domains of perceived housing

1

2

3

4

Meaning of home: physical aspects (7 items)

Meaning of home: behavioural aspects (6 items)

Meaning of home: cognitive/emotional aspects (10 items)

Usability in my home: activity aspects (4 items)

Usability in my home: physical environmental aspects (6 items)

Housing-related control beliefs: external control (16 items)

Housing satisfaction (1 item)

0.76

0.72

0.85

0.14

0.16

0.07

0.09

0.17

0.39

0.00

0.87

0.78

0.14

0.13

0.13

0.10

0.05

0.12

0.08

0.98

0.04

0.26

0.06

0.01

0.03

0.26

0.04

0.96

Note: Factor analysis using principal component analysis revealed a four-factor solution, explaining 79.0% of the variance.

0.69

0.68

0.72

0.79

0.71

0.99

0.94

ARTICLE IN PRESS

F. Oswald et al. / Journal of Environmental Psychology 26 (2006) 187–201

196

0.37 / 0.28 / 0.17

1

Physical

Aspects

1

1

1

Behavioral Cog./Emo.

Aspects

Aspects

1

Phys./Env. Hous.-rel.

External

Aspects

Control

Activity

Aspects

1

1

Meaning

of

Home

1

Usability

in the

Home

Hous.-rel.

Control

Beliefs

Satisfact.

w. Home

Conditions

1

Housing

Satisfaction

0.49 / 0.52 / 0.60

-0.10 / -0.15 / -0.16

-0.21 / -0.42 / -0.38

0.37 / 0.36 / 0.26

0.19 / 0.22 / 0.33

-0.37 / -0.39 / -0.34

Fig. 1. Confirmatory factor structure of the set of instruments on perceived housing. Note. Numbers attached to double-headed arrows: correlations for

German/Swedish/UK sample. RMSEA ¼ 0.041; NFI ¼ 0.948; CFI ¼ 0.964; w2 ¼ 78.6 (po:001).

indicating that the model now fit well with our data. That

is, perceived housing was best displayed by the selected

four constructs, reflecting four different domains, each

uniquely contributing to the understanding of perceived

housing in old age. Thus, the results from the SEM

confirmed the theoretically proposed underlying factor

structure of the four perceived housing domains meaning,

usability, external control and satisfaction.

4.3. Exploration of comparable empirical relationships

between the four domains of perceived housing in

sub-samples from three European countries (Germany,

Sweden, the UK)

Cultural differences or similarities in terms of structural

relations between the four domains were revealed in the

multi-group analysis for the three sub-samples, i.e.

Germany, Sweden, and the UK, showing relatively little

variability. Although personal and environmental background variables (see again Table 1) and objective

housing conditions could vary within and between the

sub-samples in Germany, Sweden and the UK, the findings

revealed comparable patterns of perceived housing in

different European settings, indicating an expected universality of perceived housing patterns and cross-country

usefulness of this assessment within the limited set of

research sites.

Additionally we found empirical evidence for comparability of the different magnitudes in the correlations

between the domains and respective measures due to their

level of specificity. Estimated correlations between the four

domains (and between the sub-domains MOH2 and

UMH1) are also depicted in Fig. 1. In accordance with

preceding findings (see again Table 2), correlations between

housing-related external control beliefs and housing

satisfaction showing smallest associations in all samples

(r ¼ 0:10; 0.15; 0.16), whereas usability in the home

and meaning of home showed strongest association in all

samples (r ¼ 0:49; 0.52; 0.60). Correlations between usability and meaning on one hand and housing satisfaction

and external control beliefs on the other reach a medium

level.

The experience of usability and personal meaning of

home are thus closely linked, indicating that participants

who were behaviourally, cognitive, and emotionally

attached to their homes tend to consider the home as

useful for necessary everyday activities. Particularly weak

links between housing satisfaction and external control

indicate that participants who were unsatisfied with their

homes do not necessarily feel that others are in charge of

what happens in their homes. Moreover, medium relationships between perceived usability and meaning on one

hand and housing satisfaction and control beliefs on the

other hand indicate that the four constructs reflect not only

ARTICLE IN PRESS

F. Oswald et al. / Journal of Environmental Psychology 26 (2006) 187–201

different contents of perceived housing which exist in all

three European settings but also contribute to perceived

housing in very old age more or less in the same way in all

settings.

5. Discussion

In this article empirical support was given for the

usefulness of a theoretically proposed four component

model of perceived housing across countries in old age.

First four conceptual domains of perceived housing were

introduced, covering a broad range of well-established and

innovative concepts of home evaluations. Second it was

shown that these four domains represent distinct indicators

of perceived housing on the empirical level.

In detail, bivariate correlative findings indicated some

amount of content specificity for all the measures included

into our analyses, but showed also substantial amounts of

interdependencies, pointing towards the existence of higher

order dimensions of perceived housing. Regarding our

hypothesis that a four domain model is adequate for the

understanding of perceived housing, exploratory and

confirmatory factor analyses supported the existence of

four theoretically proposed domains of perceived housing.

Exploratory factor analysis revealed that the domains

housing satisfaction, usability in the home, meaning of

home, and external housing-related control beliefs are

empirically distinct aspects of perceived housing, accordingly to the hypothesis. In other words, we found no

striking evidence for a different, ‘‘stronger’’ dimensionality

underlying the seven measures, fitting the data better than

the four-factor solution. Confirmatory factor analysis

revealed good fit of this four-factor model, hence confirming the hypothetical assumption of this pattern of perceived

housing domains in very old age. In sum, these findings

highlight that an integrated understanding of perceived

housing needs to address all these domains in a comprehensive instrument, covering the selected set of measures.

It is important to note that confirming this four-factor

model is not self-evident at all. For usability as well as for

meaning of home, evidence for a common factor underlying the different sub-domains means conceptual improvement and better understanding not implied a priori in the

measurement of these domains. For instance, a person

ranking highly in the behavioural sub-domain of meaning

of home does not necessarily need to have high scores in

the other meaning of home sub-domains as well. However,

as all sub-scales have highest loadings on the same factor,

this often happened.

Regarding the theoretical foundation of the four factors

of perceived housing, the housing satisfaction factor has

found particularly strong recognition in housing theory

and empirical research (e.g. Aragonés et al., 2002; Pinquart

& Burmedi, 2004). However, it should kept in mind that

the satisfaction rating in our study was a general evaluation

of a specific facet of housing (i.e. physical housing

conditions) and not a broad-scale assessment of housing

197

satisfaction (Heywood et al., 2002; Sixsmith & Sixsmith,

2002). What we were able to empirically support was that

this particular satisfaction rating appeared relatively

independent from the other domains of perceived housing

(see again Fig. 1). Although the single-item characteristic

of the satisfaction measure may have promoted low

correlations, one may conclude from the weak links

between housing satisfaction and external control beliefs

as well as from the moderate links between housing

satisfaction and usability or meaning of home, that the

assessment of housing satisfaction alone, as it is done quite

frequently, is far from being sufficient to assess perceived

housing in very old age.

The finding on usability as a latent construct of perceived

housing in very old age is in line with the theoretical and

empirical research related to person–environment–activity

transactions (Fänge & Iwarsson, 2003, 2005a; Iwarsson &

Ståhl, 2003; Law et al., 1996), arguing that usability can be

regarded as a combined activity-related and physical

environment-related aspect of perceived housing. The

latent factor correlations estimated from the confirmatory

factor analysis underpin the relative independence of this

dimension from other aspects of perceived housing,

showing its importance for any comprehensive characterization of the home experience in old age.

Similarly, the clear empirical support found in the

present study for one unique factor covering the subdomains measured by the meaning of home subscales, adds

to a better empirical understanding of a latent construct or

domain of common ‘‘meaningfulness’’ of the home. As has

been found, participants who consider their home as

meaningful for daily behaviour also tend to feel, for

instance, cognitive and emotional bonding to their home.

Such empirical evidence enhances the existing literature on

meaning of home, which has revealed so far as theoretically

rather rich, but empirically rather poor (Marcus, 1995;

Moore, 2000; Oswald & Wahl, 2005; Rowles & Watkins,

2003; Sixsmith, 1986).

Against the background of control theory and findings

on perceived control in different domains of life in old age

(e.g. Heckhausen & Schulz, 1995; Lachman, 1986; Levenson, 1973, 1981), the results revealed the need to address

housing-related control beliefs as an independent dimension of perceived housing in very old age. In particular, this

has been shown with respect to external housing-related

control beliefs. Thus, following theoretical assumptions on

the role of control beliefs in the domain of housing (Oswald

et al., 2003a, 2003b), this study has generated first empirical

evidence to underline the notion that this new domainspecific control dimension with particular importance for

environmental psychology is critical for the better understanding of perceived housing in late life.

In general, the estimated correlations between the four

factors are low to medium for all research sites, showing

substantial independence of the constructs of perceived

housing. Next, we further explored whether comparable

relationships between the constructs exist in three

ARTICLE IN PRESS

198

F. Oswald et al. / Journal of Environmental Psychology 26 (2006) 187–201

European sub-samples available in the ENABLE-AGE

Project, reflecting similar socio-cultural settings. As was

shown, the identified factor structure of four domains of

perceived housing were confirmed for different countryspecific urban sub-samples, indicating a great amount of

comparability in both the structural patterns of the

domains as well as the relationships between the domains

of perceived housing in Germany, Sweden, and the UK.

Thus, the results from the multi-group analyses underpin

the usefulness of the four component assessment in

different European urban settings. Comparable results in

this regard can be interpreted in terms of a validation of the

findings in different sub-samples. Moreover, the findings

provide empirical support for the assumption of comparable patterns of aspects of perceived housing in very old

age, regardless of different objective circumstances in terms

of the macro-level environment.

Besides the usefulness of our results for future research

purposes, we also see practical potential in the findings.

For example, one may consider inter-individual variation

in perceived housing as a resource or a hindrance for the

regulation of housing and quality of life at large for ageing

people. Strong bonding to the home and the related

positive evaluation of the home’s usefulness may on the

one hand positively contribute to older people’s ability to

cope with increasing problems in carrying out daily

routines and activities. On the other hand, strong bonding

may also hamper the older person’s acknowledgement of

objective problems at home or mitigate against environmental decisions like moving to an objectively better

equipped apartment. However, further studies are needed

to elucidate perceived housing aspects in relation to

everyday problem-solving in later life.

Of course, these findings are subject to limitations. Five

issues should be stressed in this regard: First, three

subscales from the domains of usability, meaning of home

and housing-related control beliefs—that is, personal and

social aspects of usability, social meanings of home and

internal control beliefs—were discarded from the empirical

analyses due to poor psychometric quality. This has

weakened somewhat our empirical argument towards a

rather comprehensive assessment of perceived housing, as

three measures related to our main constructs are not used.

However, note that in the domains of usability and

meaning of home, it was possible to include two out of

three sub-scales (usability) and three out of four sub-scales

(meaning) thus covering substantially the concepts’ semantic substance. Regarding the inclusion of external control

only, it should be noted that findings from longitudinal

studies suggest that external control beliefs are particular

sensitive to age-related changes, and thus, crucial in

explaining independence in daily living and well-being in

old age (e.g. Baltes et al., 1999; Clark-Plaskie & Lachman,

1999). Therefore, we believe that the sole consideration of

external control, while being a limitation of our study,

addresses a major facet of the full control dynamics picture

as people age. There is nevertheless a clear need for the

optimization of the subscales dropped in the present study

in order to show that our argumentation of four distinct

dimensions of perceived housing still holds, when all

subscales considered of theoretical importance are also

part of the measurement model.

Second, the set of concepts and measures in our study

may not be sufficient to cover all facets of perceived

housing. In particular, the single-item measure of satisfaction with housing conditions may be seen as a too rough

measure to represent the full housing satisfaction domain

(e.g. Aragonés et al., 2002; Pinquart & Burmedi, 2004).

However, due to limitations in the duration of interview

capacity of very old persons, some choices had to be made.

Hence we emphasized those domains not yet well

established in relation to perceived housing, such as control

beliefs, usability, and meaning of home and assessed

housing satisfaction in relation only to physical housing

conditions.

Third, as already argued, the single-item measure on

housing satisfaction may be seen as a methodological

shortcoming, as single-item measures could be regarded as

more sensitive to measurement error than multi-item

measures, which might lower their correlations with other

indicators (Anastasi, 1988; Epstein, 1983). However, there

is also considerable evidence indicating sufficient psychometric quality of single-item satisfaction measures (Scherpenzeel, 1995; Veenhoven, 1996).

A fourth limitation may be seen in the generalization of

the findings in terms of a ‘‘universal’’ pattern of perceived

housing in very old age. Although we analysed data from

three different European settings and the results are rather

comparable in these settings, the findings are based on a

selected set of countries with relatively similar cultural

backgrounds. Data from other sites, reflecting more

cultural variety, would be needed to fully address the

question of universality of the structure of perceived

housing (Hay, 1998; Miller, 2001).

Finally, our sample consisted of very old adults living

alone in their community dwellings. Thus, the present

study is limited in its potential to reflect the full range of the

ageing population, such as those being ‘‘young-old’’, i.e.

about 60–80 years of age, cohabiting older people, or older

adults living in institutional settings.

Taken together, insights from our study support the

assumption that the complexity of home (see again our case

example) has been underestimated in earlier research.

While measuring the subjective perception of home using

the measures adapted in the paper produces a promising

and rather comprehensive application, the in-depth understanding of how the home is perceived by very old persons

might be a valuable goal for further research. For example,

qualitative methods might expand our conceptual models.

Bringing together quantitative and qualitative approaches

of perceived housing would herald a new era of research on

perceived home whereby process oriented perspectives on

person–home transactions can be meaningfully pursued

(Oswald & Rowles, 2006).

ARTICLE IN PRESS

F. Oswald et al. / Journal of Environmental Psychology 26 (2006) 187–201

Another set of findings from the ENABLE-AGE project

published elsewhere have provided evidence that both

objective characteristics of the home environment and the

subjective experience of home are crucially related with

health and well-being of very old people (Iwarsson,

Nygren, &, Slaug, 2005; Iwarsson, Sixsmith, et al., 2005;

Oswald et al., in press). Thus, further research may address

the complexity of perceived housing in relation to objective

housing conditions such as accessibility and prevalence of

environmental barriers, as well as to age-related outcome

variables, such as independence and well-being. In particular, the mediating impact of perceived housing in order

to maintain or even enhance ‘‘healthy ageing’’ in very old

age seems a promising research objective. Perceived

housing may serve as a resource or mediator to cope with

functional loss in very old age (e.g. due to the environmental press-competence model proposed by Lawton &

Nahemow, 1973) or in addition to processes of home

adaptation and environmental centralisation (Gitlin, 1998;

Rubinstein & Parmelee, 1992).

In terms of application, the findings can contribute to

enrich and strengthen the user’s perspective on perceived

housing in housing counselling and home adaptation

practice (e.g. Fänge & Iwarsson, 2005a, 2005b; Lanspery

& Hyde, 1997). In particular, the current focus on barrier

free building standards needs to be widened to encompass a

more holistic approach that takes seriously both the

objective and subjective, ‘‘invisible’’ aspects of the home.

Housing, health and social care professionals need to be

aware of the importance of the home in the lives of their

clients and to include housing solutions within a multidisciplinary approach to assessment and care planning. In

this regard the current findings can show that perceived

home in old age covers a whole range of housing

experiences beyond mere support and functionality, as it

is reflected, for instance, in the cognitive/emotional aspects

of meaning of home. Using an integrative, comprehensive,

and parsimonious assessment of perceived housing in old

age can sensitize housing professionals to a holistic

approach in order to find individualized and customized

housing solutions (Connell & Sanford, 1997). However,

further steps towards the development of an easy assessment and evaluation procedure of these measures are

needed.

In conclusion, evidence presented in the present paper

suggests that perceived housing in very old age is well

covered by a set of theoretically informed concepts and

related measures, addressing housing satisfaction, usability

in the home, meaning of home and housing-related

external control. That is, a rather comprehensive understanding of perceived housing needs to cover the scope of

personal links to the home (meaning), perceived functional

activity possibilities at home (usability), a global evaluation

perspective (satisfaction) and the perceived agency related

challenges of housing in later life (control). The provided

set of measures was found to be useful to reflect the

proposed domains of perceived housing for very old elders

199

living alone in their urban community dwellings, although

psychometric optimisation of perceived housing measures

still is a challenge and deserves more instrument refinement.

References

Altman, I., & Low, S. M. (Eds.) (1992). Place attachment (Vol. 12). New

York: Plenum Press.

Anastasi, A. (1988). Psychological testing (6th ed). New York: Macmillan.

Aragonés, J. I., Francescato, G., & Gärling, T. (2002). Residential

environments. Choice, satisfaction, and behavior. Westport, CT: Bergin

& Gervey.

Baltes, M. M., Freund, A. M., & Horgas, A. L. (1999). Men and women in

the berlin aging study. In P. B. Baltes, & K. U. Mayer (Eds.), The

berlin aging study (pp. 259–281). Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Baltes, M. M., Maas, I., Wilms, H. U., Borchelt, M., & Little, T. (1999).

Everyday competence in old and very old age: Theoretical considerations and empirical findings. In P. B. Baltes, & K. U. Mayer (Eds.),

The berlin aging study. Aging from 70 to 100 (pp. 384–402). Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York:

Wiley.

Brown, B. B., & Perkins, D. D. (1992). Disruptions in place attachment. In

I. Altman, & S. M. Low (Eds.), Place attachment (pp. 279–304). New

York: Plenum Press.

Christensen, D. L., Carp, F. M., Cranz, G. L., & Whiley, J. A. (1992).

Objective housing indicators as predictors of the subjective evaluations

of elderly residents. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 12, 225–236.

Clark-Plaskie, M., & Lachman, M. E. (1999). The sense of control in

midlife. In S. L. Willis, & J. D. Reid (Eds.), Life in the middle:

Psychological and social development in middle age (pp. 181–208). San

Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Connell, B. R., & Sanford, J. A. (1997). Individualizing home modification

recommendations to facilitate performance of routine activities. In S.

Lanspery, & J. Hyde (Eds.), Staying put. Adapting the places instead of

the people (pp. 113–147). Amityville, NY: Baywood.

Després, C. (1991). The meaning of home: Literature review and directions

for future research and theoretical development. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 8, 96–155.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective

well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125,

276–302.

Epstein, S. (1983). Aggregation and beyond: Some basic issues on the

prediction of behavior. Journal of Personality, 51, 360–392.

Fänge, A., & Iwarsson, S. (1999). Physical housing environment—

development of a self-assessment instrument. Canadian Journal of

Occupational Therapy, 66, 250–260.

Fänge, A., & Iwarsson, S. (2003). Accessibility and usability in housing—

Construct validity and implications for research and practice.

Disability and Rehabilitation, 25, 1316–1325.

Fänge, A., & Iwarsson, S. (2005a). Changes in ADL dependence and

aspects of usability following housing adaptation—A longitudinal

perspective. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 59, 296–304.

Fänge, A., & Iwarsson, S. (2005b). Changes in accessibility and aspects of

usability in housing over time—An exploration of the housing

adaptation process. Occupational Therapy International, 12, 44–59.

Gitlin, L. N. (1998). Testing home modification interventions: Issues of

theory, measurement, design, and implementation. In R. Schulz, G.