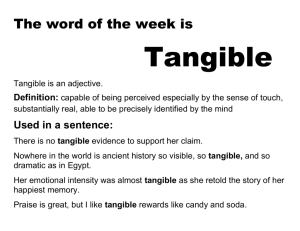

Guide to Accounting for and Reporting Tangible Capital Assets

advertisement