13.0 Intravenous (IV) cannulation

advertisement

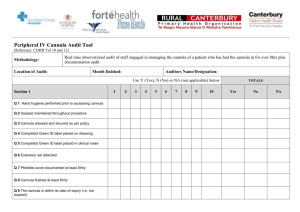

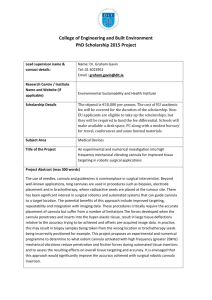

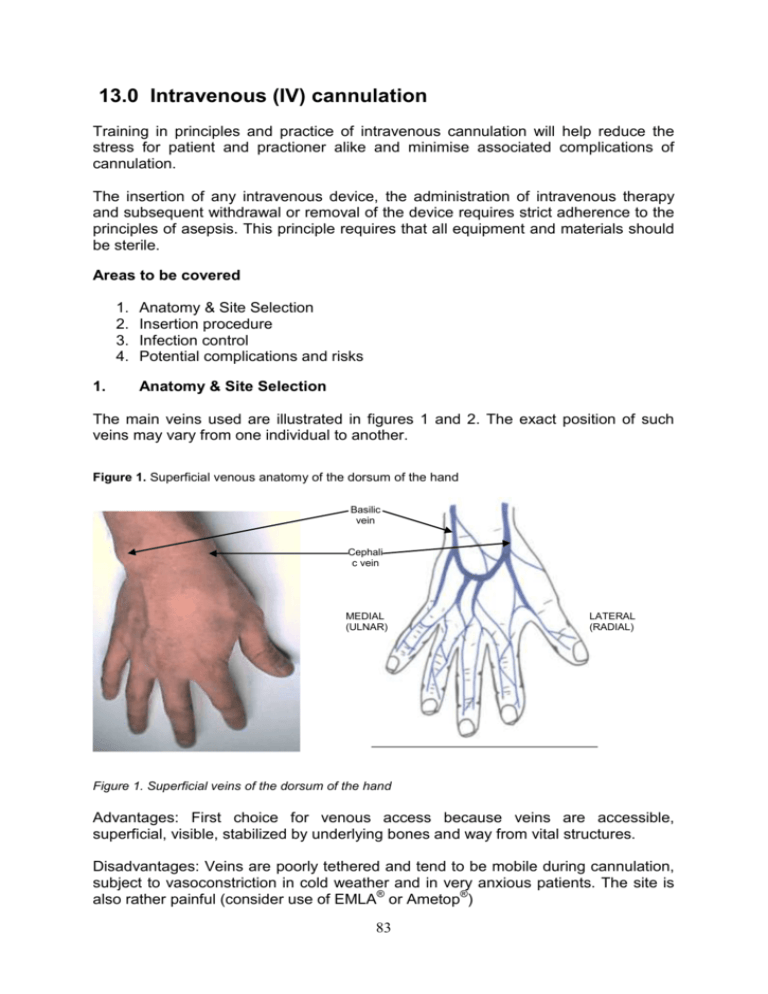

13.0 Intravenous (IV) cannulation Training in principles and practice of intravenous cannulation will help reduce the stress for patient and practioner alike and minimise associated complications of cannulation. The insertion of any intravenous device, the administration of intravenous therapy and subsequent withdrawal or removal of the device requires strict adherence to the principles of asepsis. This principle requires that all equipment and materials should be sterile. Areas to be covered 1. 2. 3. 4. 1. Anatomy & Site Selection Insertion procedure Infection control Potential complications and risks Anatomy & Site Selection The main veins used are illustrated in figures 1 and 2. The exact position of such veins may vary from one individual to another. Figure 1. Superficial venous anatomy of the dorsum of the hand Basilic vein Cephali c vein MEDIAL (ULNAR) LATERAL (RADIAL) Figure 1. Superficial veins of the dorsum of the hand Advantages: First choice for venous access because veins are accessible, superficial, visible, stabilized by underlying bones and way from vital structures. Disadvantages: Veins are poorly tethered and tend to be mobile during cannulation, subject to vasoconstriction in cold weather and in very anxious patients. The site is also rather painful (consider use of EMLA® or Ametop®) 83 Figure 2. Vascular anatomy of the Right antecubital fossa and ventral arm Cephali c vein Biceps muscle Basilic vein Biceps tendon Median cephalic vein Median vein LATERAL (RADIAL) MEDIAL (ULNAR) Brachial artery Radial artery Ulnar artery LATERAL (RADIAL) MEDIAL (ULNAR) Figure 2. Vascular anatomy of the upper arm (including the antecubital fossa) Second choice for venous cannulation (first if large volumes of fluids need to be given quickly) is the large veins of the antecubital fossa – the cephalic (lateral) and basilic (medial) veins. Because of the proximity of the brachial artery and median nerve to the basilic vein, the Cephalic vein in its lateral position is usually the vein of choice. Advantages: Larger veins, which are usually well tethered and even when not readily visualised, are usually palpable. Disadvantages: The proximity to vital structures (as above) and movement at the elbow joint (an arm board may be needed if the patient is unable to keep the arm straight themselves). Veins and Sites to Use (in general): Distal veins first Easily palpable veins with good capillary refill (it is better to go for a vein you can palpate but not see, rather than a vein you can see but not feel). Veins in the non-dominant side Veins opposite to surgical operation side Veins with largest diameter (in general) 84 Veins clear of vital structures such as arteries (a major advantage of the dorsum of the hand) Veins and Sites to Avoid (in general): Areas of flexion Veins close to arteries (e.g. medial veins of the antecubital fossa) Obvious valves Small visible superficial veins Veins affected by previous use or sclerosed (e.g. in IV drug abusers) Infected sites Broken skin Limb to be involved in future surgery (e.g. for radial forearm free flap) Vessels distal to a fracture Methods of improving venous filling: Soft quick release tourniquet applied proximal to the cannulation site Open and closing the fist Lower the limb below the level of the heart Gentle slapping over vessel (this causes a minor inflammatory response with histamine release and vasodilation) Application of warmth – warm compress or emersion of the limb (or opposite limb) in warm water Time – allow filling, don’t rush 2. Insertion procedure The key to successful cannulation (and thus minimising stress to patient and clinician alike) is careful preparation of the chosen site and good well-practiced technique. Pre-cannulation assessment Obtain informed consent (usually verbal) Check treatment plan Note relevant medical history – particularly any allergies Use tourniquet to assess suitability of veins – try an alternative site if a vein is not readily identified Equipment (ensure all products are in-date) Skin cleanser (such as Steret®) – allow to dry before cannulation and avoid contact with prepared site Tourniquet Dressing pack (or surgical tape) – to secure cannula. Should allow visual inspection of the insertion site 85 Cannula – smallest appropriate cannula should be used. The size of cannula depends on the reason for cannulation. The most widely used canulae are “venflons”. For IV drugs a blue or pink venflon may be appropriate. If repeated doses have been prescribed, keep the cannula patent with either a slow infusion of crystalloid or by regular flushes with a dilute heparin solution. For routine IV infusion of crystalloid use a pink or green venflon. For rapid infusion of crystalloid or blood transfusion use a brown venflon. The rate of infusion is dependent on the cannula NOT the vein. Use a short, wide cannula for rapid infusions (“short & thick does the trick” i.e a brown venflon) Latex gloves Sharps container Intravenous flush – sterile saline or water for injection Luer lock connection or bung Environment Bed or seating for the patient Seating for the practioner Well supported limb Good lighting Trolley or tray for equipment (Cannulation should not be performed in carpeted areas unless steps have been taken to ensure any potential blood spillage can be contained by fluid resistant preparation sheet beneath the cannulation site) Always use aseptic technique 86 INSERTION PROCEDURE Prepare patient Prepare equipment Wash hands Put on gloves Skin preparation Apply tourniquet Adopt appropriate cannula grip Ensure cannula is bevel up Apply skin traction Angulation 10-30° - dependent on vein depth Insert cannula and look for venous blood (dark) in flashback chamber Lower angle of cannula and advance 2mm Retract stylet 3-4mm, note secondary flashback along cannula and advance cannula into position Release tourniquet Apply digital pressure beyond cannula tip or elevate limb above the level of the heart Remove stylet and dispose of in sharps container or on sharps pad Attach Luer lock connection Hold cannula in place and flush to ensure correct positioning (usually prior to securing with tape) Secure cannula with dressing Document procedure 87 3. Infection control There are many potential sources of contamination, which may result in infection during IV cannulation. Standard precautions should be taken for all procedures to minimise infection risk before, during and after cannulation. Bacteria and viruses are the most common infectious agents. Standard precautions Skin The practioner must cover all cuts or abrasions with a waterproof dressing Gloves Well fitting, clean gloves must be worn throughout the procedure to prevent contamination of the hands by blood/body fluids. Latex is the material of choice unless contraindicated. Handwashing Thorough handwashing is still essential and is the fundamental universal precaution between procedures and patients Aprons Where there is a possibility of blood spillage Eye protection Wear if there is danger of blood/body fluid splashes Sharps Container NO needle re-sheathing prior to disposal into a sharps container 4. Potential complications and risks Phlebitis Phlebitis (inflammation of the vein) is the most common complication with peripheral IV cannulation. 3 types of phlebitis are recognised: i. Chemical ii. Mechanical iii. Infective Management of cannulation related infections Remove cannula Send cannula tip for culture and sensitivity Implement local treatment protocol Replace cannula (at alternate site) and continue therapy as prescribed with a fresh cannula Other potential complications: Haematoma, infiltration, extravasation, air embolism, catheter embolism, transfixation, intra-arterial injection. 88 Extravasation Seen when the cannula fails to penetrate the lumen of the vein completely or completely transects the vein and results in the cannula lying in the subcutaneous tissues. Flushing with saline results in a lump – if seen fluid should be discontinued and the site massaged to disperse the fluid or drug. If a significant quantity of fluid has been extravasated it may require drainage to stop necrosis. Extravasation is more of a concern with irritant substances such as Diazepam, TPN (total parenteral nutrition), glucose or barbiturates. Intra-arterial injection Is a rare complication of IV cannulation due to incorrect positioning of a cannula into an artery. Avoided by good IV cannulation technique and choice of most appropriate veins, away from other vital structures (as above). When using veins of the antecubital fossa only those superficial and lateral to the biceps tendon should usually be used in order to avoid the median nerve and brachial artery. If bright red rather than dark blood is observed in the flashback chamber this indicates intraarterial cannulation. The patient will report pain and a test flush with 0.9% saline will classical produce pain radiation down the arm. If observed, injection should be terminated immediately, the cannula should be removed, firm pressure applied and the arm should be elevated to prevent haematoma formation. The main concern with intra-arterial injection is the potential for arterial spasm (seen with injection of irritant drugs e.g. diazepam). Brachial artery spasm is dangerous characterised by intense burning radiating towards the hand, blanching of the skin and weakening and eventually loss of radial and ulnar pulses. Without prompt treatment blood coagulates, causing thrombosis, ischaemia and ultimately gangrene. Treatment involves keeping cannula in situ and injection of 1% procaine to promote vasodilatation and pain relief and transfer of the patient to hospital for further treatment, including the use of anticoagulants such as heparin. Risks to healthcare workers (HCW) Incidence of sharps injuries: Account for 16% of all hospital related injuries 16% are related to cannulation 24% are phlebotomy related Risk of acquiring infection from needle stick injury (from a known carrier): Hep B virus Hep C virus HIV 1 in 3 1 in 100 1 in 300 Best and safest practice Where gloves whenever potential blood contact is anticipated Change gloves between patients 89 Use eye protection Avoid sharps were possible Keep up to date with current practice including local policies and new, safer equipment ALL blood exposure or needle stick injuries should be reported and appropriate action taken (see below) Inoculation injuries Inoculation injuries are the most likely route for transmission of blood-borne viral infections. Definition of inoculation injury Includes all incidents where a contaminated object or substance breaches the integrity of the skin or mucous membranes or comes into contact with the eyes. Typical types: Sticking or stabbing with a used needle or instrument Splashes with contaminated substance top the eye or other open lesion Cuts with contaminated equipment Bites or scratches inflicted by patients Treatment – inoculation injuries must be dealt with promptly Injury Allow wound to bleed (not scrubbed) and washed thoroughly with running water, place waterproof dressing Risk assessment including immune status of „victim‟ +/- carrier status Seek urgent advice according to the local arrangements re follow up and whether serological surveillance is necessary Every hospital will have at least one designated specialist eg consultant microbiologist to contact re advice on postexposure prophylaxis A full record of the incident should be recorded in the accident / incident book. 90 All dental practices and hospital dental and oral surgery departments should have an incident book for recording a variety of incidents. In addition to this, surgeries and departments should have local rules/protocols in place for the management of so called „needle-stick‟ injuries. Such protocols reduce the risk of omissions in the management of individuals and help ensure an accurate and contemporaneous record of the incident is kept for current and future reference. The location of this should be known by all staff and a „lead‟ clinician should be identified for reference. In the situation described, the injured member of staff (victim for descriptive purposes) should allow the injured site to bleed and the site should be washed thoroughly with soap under running water. The site should not be scrubbed as this may further disperse the contamination. The site should then be covered with a waterproof plaster. The person should then report the incident immediately to the „lead‟ individual so that the reporting and assessment process may begin. The name of the injured party and their position should be recorded together with that of the assessing individual should be recorded in the incident book. The time of the injury, nature of injury, the anatomical site, and the location in the practice were the injury occurred should be recorded. The nature of the injury is important. A penetrating injury as recorded here represents a higher risk of infection transmission than a scratch type injury for example. The instrument itself should be examined as to its type and degree of contamination (e.g. visible blood) – this should again be recorded. Different types of instruments pose different risks. Solid instruments will represent a low risk to transmission. A hollow instrument such as a needle will constitute a higher risk especially if there is significant donor material present. These components ie injury type and particulars of the instrument involved are aspects of the risk assessment. The hepatitis B status of the victim should be established (NB all clinical staff should be immunised against Hepatitis B and a record of their current anti-HBs level should be kept up to date – currently the level recommended to provide cover is >100mIU/ml). If possible the viral carrier status of the source patient should be ascertained. The later may only be possible if the source is known and requires seeking their expressed consent and liaison with local occupational health departments. Once a risk assessment has been performed if there is any concern in respect of injury type, victim immunisation or status of source, urgent advice should be sort from the local occupational health service. At this stage an incident form should be completed. Risk of acquiring HIV infection following an inoculation injury is small. If the injury is assessed as significant for transmission of HIV based on the following: 1. 2. 3. 4. Deep injury to the health care worker (implied but not specified in this essay) Visible blood on the device causing injury Device previously placed in patient‟s vein or artery Source patient within last 60days of life (ie late stage AIDS) 91 …and the source patient is HIV infected, the use of antiretroviral drugs taken prophylactically ASAP after exposure (ideally within 1hour) is recommended. Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) involves a short course (4weeks) of antiretroviral drug treatment in an attempt to further reduce the risk of infection with HIV References 1. Girdler N M, Hill C M, Sedation in Dentistry. Wright 1998 2. BD Medical Systems Intravenous Cannulation Training Programme 92