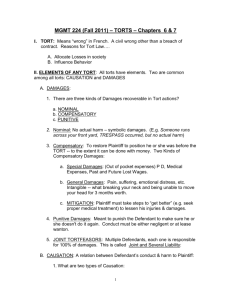

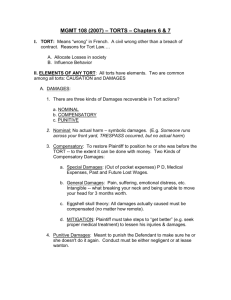

Fault(s) in Negligence Law, The

advertisement