Cash Management

advertisement

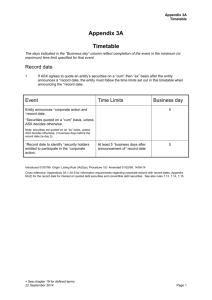

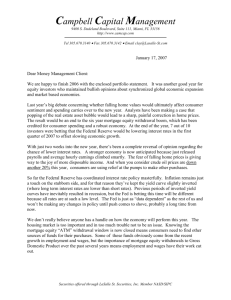

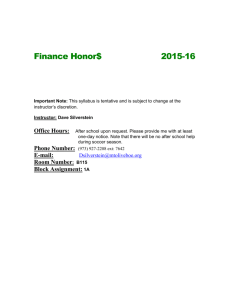

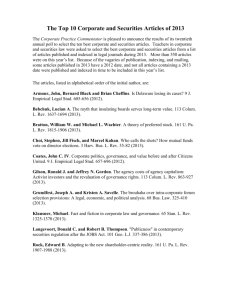

___ Cas h M a na g e m ent KEY NOTATIONS Fixed cost of selling securities to replenish cash Lower control limit Opportunity cost of holding cash Cost of debt capital Total amount of new cash needed for transaction purposes Upper control limit Target cash balance F L R RB T U Z 27 PART Seven Chapter As most people know, many banks ran out of cash in 2008 and 2009 as bad debts, lack of short-term financing and poor profitable opportunities combined to cause the most severe crisis in the financial sector for decades. Governments stepped into the breach and used taxpayers’ money to shore up their institutions. The non-financial sector was also seriously affected. All across Europe construction companies and other firms, such as estate agents, found that they had no cash, because the housing market was almost non-existent. The automobile industry suffered deeply, and many firms changed their manufacturing strategy, made workers redundant, and cut production to save cash. Cash is one of the most important issues a firm needs to consider. Even if a firm is growing and has excellent performance, if it runs out of cash it cannot survive. In this chapter we examine cash management and the various issues a firm must consider. 27.1 Reasons for Holding Cash The term cash is a surprisingly imprecise concept. The economic definition of cash includes currency, savings account deposits at banks, and undeposited cheques. However, financial managers often use the term cash to include short-term marketable securities. Short-term marketable securities are frequently referred to as cash equivalents and include Treasury bills, certificates of deposit, and repurchase agreements. (Several different types of short-term marketable security are described at the end of this chapter.) The balance sheet item ‘cash’ usually includes cash equivalents. The previous chapter discussed the management of net working capital. Net working capital includes both cash and cash equivalents. This chapter is concerned with cash, not net working capital, and it focuses on the narrow economic definition of cash. The basic elements of net working capital management, such as carrying costs, shortage costs and opportunity costs, are relevant for cash management. However, cash management is concerned more with how to minimize cash balances by collecting and disbursing cash effectively. There are two primary reasons for holding cash. First, cash is needed to satisfy the transactions motive. Transaction-related needs come from normal disbursement and collection activities of the firm. The disbursement of cash includes the payment of wages and salaries, trade debts, taxes and dividends. Cash is collected from sales from operations, sales of assets, and new financing. The cash inflows (collections) and outflows (disbursements) are not perfectly synchronized, and some level of cash holdings is necessary as a buffer. If the firm maintains too small a cash balance it may run out of cash. If so, it must sell marketable securities or borrow. Selling marketable securities and borrowing involve trading costs. ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 745 6/11/09 10:13:42 AM ___ 746 Chapter 27 Cash Management FIGURE 27.1 Total costs of holding cash Cost of holding cash Opportunity costs Trading costs are increased when the firm must sell securities to establish a cash balance. Opportunity costs are increased when there is a cash balance, because there is no return to cash. Trading costs C* Optimal size of cash balance Size of cash balance (C) Figure 27.1 Costs of holding cash Another reason to hold cash is for compensating balances. Cash balances are kept at banks to compensate for banking services rendered to the firm. The cash balance for most firms can be thought of as consisting of transaction balances and compensating balances. However, it would not be correct for a firm to add the amount of cash required to satisfy its transaction needs to the amount of cash needed to satisfy its compensatory balances to produce a target cash balance. The same cash can be used to satisfy both requirements. The cost of holding cash is, of course, the opportunity cost of lost interest. To determine the target cash balance, the firm must weigh the benefits of holding cash against the costs. It is generally a good idea for firms to figure out first how much cash to hold to satisfy transaction needs. Next, the firm must consider compensating balance requirements, which will impose a lower limit on the level of the firm’s cash holdings. Because compensating balances merely provide a lower limit, we ignore compensating balances for the following discussion of the target cash balance. 27.2 Determining the Target Cash Balance The target cash balance involves a trade-off between the opportunity costs of holding too much cash and the trading costs of holding too little. Figure 27.1 presents the problem graphically. If a firm tries to keep its cash holdings too low, it will find itself selling marketable securities (and perhaps later buying marketable securities to replace those sold) more frequently than if the cash balance was higher. Thus trading costs will tend to fall as the cash balance becomes larger. In contrast, the opportunity costs of holding cash rise as the cash holdings rise. At point C* in Fig. 27.1, the sum of both costs, depicted as the total cost curve, is at a minimum. This is the target or optimal cash balance. The Baumol Model William Baumol was the first to provide a formal model of cash management incorporating opportunity costs and trading costs.1 His model can be used to establish the target cash balance. Suppose Golden Socks plc began week 0 with a cash balance of C = £1.2 million, and outflows exceed inflows by £600,000 per week. Its cash balance will drop to zero at the end of week 2, and its average cash balance will be C/2 = £1.2 million/2 = £600,000 over the two-week period. At the end of week 2 Golden Socks must replace its cash either by selling marketable securities or by borrowing. Figure 27.2 shows this situation. ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 746 6/11/09 10:13:45 AM Determining the Target Cash Balance FIGURE 27.2 747 ___ Starting cash: C = £1,200,000 Average cash £600,000 = C/2 Ending cash: 0 0 1 2 3 4 Golden Socks plc begins week 0 with cash of £1,200,000. The balance drops to zero by the second week. The average cash balance is C/2 = £1,200,000/2 = £600,000 over the period. Weeks Figure 27.2 Cash balances for Golden Socks plc If C were set higher, say at £2.4 million, cash would last four weeks before the firm would need to sell marketable securities, but the firm’s average cash balance would increase to £1.2 million (from £600,000). If C were set at £600,000, cash would run out in one week, and the firm would need to replenish cash more frequently, but its average cash balance would fall from £600,000 to £300,000. Because transaction costs must be incurred whenever cash is replenished (for example, the brokerage costs of selling marketable securities), establishing large initial cash balances will lower the trading costs connected with cash management. However, the larger the average cash balance, the greater the opportunity cost (the return that could have been earned on marketable securities). To solve this problem, Golden Socks needs to know the following three things: F = The fixed cost of selling securities to replenish cash. T = The total amount of new cash needed for transaction purposes over the relevant planning period – say, one year. and R = The opportunity cost of holding cash: this is the interest rate on marketable securities. With this information, Golden Socks can determine the total costs of any particular cashbalance policy. It can then determine the optimal cash-balance policy. The Opportunity Costs The total opportunity costs of cash balances, in monetary terms, must be equal to the average cash balance multiplied by the interest rate: Opportunity costs (£) = (C/2) × R The opportunity costs of various alternatives are given here: Initial cash balance, C (£) Average cash balance, C/2 (£) Opportunity costs, (C/2) ´ R (R = 0.10) (£) 4,800,000 2,400,000 240,000 2,400,000 1,200,000 120,000 1,200,000 600,000 60,000 600,000 300,000 30,000 300,000 150,000 15,000 The Trading Costs We can determine total trading costs by calculating the number of times that Golden Socks must sell marketable securities during the year. The total amount of cash disbursement during the year is £600,000 × 52 weeks = £31.2 million. If the initial cash balance is set at £1.2 million, Golden Socks will sell £1.2 million of marketable securities every two weeks. Thus trading costs are given by ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 747 6/11/09 10:13:48 AM 748 ___ Chapter 27 Cash Management £31.2 million × F = 26 F £1.2 million The general formula is Trading costs (£) = (T/C) × F A schedule of alternative trading costs follows: Total disbursements during relevant period, T (£) Initial cash balance, C (£) Trading costs, (T/C) ´ F (F = £1,000) (£) 31,200,000 4,800,000 6,500 31,200,000 2,400,000 13,000 31,200,000 1,200,000 26,000 31,200,000 600,000 52,000 31,200,000 300,000 104,000 The Total Cost The total cost of cash balances consists of the opportunity costs plus the trading costs: Total cost = Opportunity costs + Trading costs = (C/2) × R + (T/C) × F Cash balance (£) Total cost (£) = Opportunity costs (£) + Trading costs (£) 4,800,000 246,500 240,000 6,500 2,400,000 133,000 120,000 13,000 1,200,000 86,000 60,000 26,000 600,000 82,000 30,000 52,000 300,000 119,000 15,000 104,000 The Solution We can see from the preceding schedule that a £600,000 cash balance results in the lowest total cost of the possibilities presented: £82,000. But what about £700,000, or £500,000, or other possibilities? To determine minimum total costs precisely, Golden Socks must equate the marginal reduction in trading costs as balances rise with the marginal increase in opportunity costs associated with cash balance increases. The target cash balance should be the point where the two offset each other. This can be calculated with either numerical iteration or calculus. We shall use calculus; but if you are unfamiliar with such an analysis, you can skip to the solution. Recall that the total cost equation is Total cost (TC) = (C/2) × R + (T/C) × F If we differentiate the TC equation with respect to the cash balance and set the derivative equal to zero, we shall find dTC R TF = − 2 =0 dC 2 C Marginal Marginal Marginal2 = = total cost opportunity costs trading costs We obtain the solution for the general cash balance, C*, by solving this equation for C: ___ R TF = 2 C2 C * = 2TF /R Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 748 6/11/09 10:13:50 AM Determining the Target Cash Balance 749 ___ If F = £1,000, T = £31,200,000, and R = 0.10, then C* = £789,936.71. Given the value of C*, opportunity costs are £789, 936.71 × 0.10 2 = £39, 496.84 (C * 2 ) × R = Trading costs are £31, 200, 000 × 1, 000 £789, 936.71 = £39, 496.84 (TC *) × F = Hence total costs are £39,496.84 + £39,496.84 = £78,993.68 Limitations The Baumol model represents an important contribution to cash management. The limitations of the model include the following: 1 The model assumes the firm has a constant disbursement rate. In practice, disbursements can be only partially managed, because due dates differ, and costs cannot be predicted with certainty. 2 The model assumes there are no cash receipts during the projected period. In fact, most firms experience both cash inflows and outflows daily. 3 No safety stock is allowed. Firms will probably want to hold a safety stock of cash designed to reduce the possibility of a cash shortage or cash-out. However, to the extent that firms can sell marketable securities or borrow in a few hours, the need for a safety stock is minimal. The Baumol model is possibly the simplest and most stripped-down, sensible model for determining the optimal cash position. Its chief weakness is that it assumes discrete, certain cash flows. We next discuss a model designed to deal with uncertainty. The Miller–Orr Model Merton Miller and Daniel Orr developed a cash balance model to deal with cash inflows and outflows that fluctuate randomly from day to day.2 In the Miller–Orr model both cash inflows and cash outflows are included. The model assumes that the distribution of daily net cash flows (cash inflow minus cash outflow) is normally distributed. On each day the net cash flow could be the expected value or some higher or lower value. We shall assume that the expected net cash flow is zero. Figure 27.3 shows how the Miller–Orr model works. The model operates in terms of upper (U) and lower (L) control limits and a target cash balance (Z). The firm allows its cash balance to wander randomly within the lower and upper limits. As long as the cash balance is between U and L, the firm makes no transaction. When the cash balance reaches U, such as at point X, the firm buys U − Z units (e.g. euros or pounds) of marketable securities. This action will decrease the cash balance to Z. In the same way, when cash balances fall to L, such as at point Y (the lower limit), the firm should sell Z − L securities and increase the cash balance to Z. In both situations cash balances return to Z. Management sets the lower limit, L, depending on how much risk of a cash shortfall the firm is willing to tolerate. Like the Baumol model, the Miller–Orr model depends on trading costs and opportunity costs. The cost per transaction of buying and selling marketable securities, F, is assumed to be fixed. The percentage opportunity cost per period of holding cash, R, is the daily interest rate on marketable securities. Unlike in the Baumol model, the number of transactions per period is a random variable that varies from period to period, depending on the pattern of cash inflows and outflows. ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 749 6/11/09 10:13:51 AM 750 ___ Chapter 27 Cash Management FIGURE 27.3 Cash U Z L X U is the upper control limit. L is the lower control limit. The target cash balance is Z. As long as cash is between L and U, no transaction is made. Y Time Figure 27.3 The Miller–Orr model As a consequence, trading costs per period depend on the expected number of transactions in marketable securities during the period. Similarly, the opportunity costs of holding cash are a function of the expected cash balance per period. Given L, which is set by the firm, the Miller–Orr model solves for the target cash balance, Z, and the upper limit, U. Expected total costs of the cash balance return policy (Z, U) are equal to the sum of expected transaction costs and expected opportunity costs. The values of Z (the return cash point) and U (the upper limit) that minimize the expected total cost have been determined by Miller and Orr: Z* = U* = 3Z* − 2L 3 3 Fs 2 ( 4 R ) + Z Here * denotes optimal values, and s2 is the variance of net daily cash flows. The average cash balance in the Miller–Orr model is Average cash balance = EXAMPLE 27.1 4Z − L 3 Miller–Orr To clarify the Miller–Orr model, suppose F = £1,000, the interest rate is 10 per cent annually, and the standard deviation of daily net cash flows is £2,000. The daily opportunity cost, R, is (1 + R)365 − 1 = 0.10 1 + R = 365 1.10 = 1.000261 R = 0.000261 The variance of daily net cash flows is s 2 = (2,000)2 = 4,000,000 Let us assume that L = 0: Z* = 3 (3 × £1,000 × 4,000,000 ) (4 × 0.000261) + 0 = 3 £11,493,900,000,000 = £22,568 U * = 3 × £22,568 = £67,704 ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 750 6/11/09 10:13:56 AM Managing the Collection and Disbursement of Cash 751 ___ 4 × £22,568 3 = £30,091 Average cash balance = Implications of the Miller–Orr Model To use the Miller–Orr model, the manager must do four things: 1 Set the lower control limit for the cash balance. This lower limit can be related to a minimum safety margin decided on by management. 2 Estimate the standard deviation of daily cash flows. 3 Determine the interest rate. 4 Estimate the trading costs of buying and selling marketable securities. These four steps allow the upper limit and return point to be computed. Miller and Orr tested their model using nine months of data for cash balances for a large industrial firm. The model was able to produce average daily cash balances much lower than the averages actually obtained by the firm.3 The Miller–Orr model clarifies the issues of cash management. First, the model shows that the best return point, Z*, is positively related to trading costs, F, and negatively related to R. This finding is consistent with and analogous to the Baumol model. Second, the Miller–Orr model shows that the best return point and the average cash balance are positively related to the variability of cash flows. That is, firms whose cash flows are subject to greater uncertainty should maintain a larger average cash balance. Other Factors Influencing the Target Cash Balance Borrowing In our previous examples the firm obtained cash by selling marketable securities. Another alternative is to borrow cash. Borrowing introduces additional considerations to cash management: 1 Borrowing is likely to be more expensive than selling marketable securities, because the interest rate is likely to be higher. 2 The need to borrow will depend on management’s desire to hold low cash balances. A firm is more likely to need to borrow to cover an unexpected cash outflow with greater cash flow variability and lower investment in marketable securities. Compensating Balance The costs of trading securities are well below the lost income from holding cash for large firms. Consider a firm faced with either selling £2 million of Treasury bills to replenish cash or leaving the money idle overnight. The daily opportunity cost of £2 million at a 10 per cent annual interest rate is 0.10/365 = 0.027 per cent per day. The daily return earned on £2 million is 0.00027 × £2 million = £540. The cost of selling £2 million of Treasury bills is much less than £540. As a consequence, a large firm will buy and sell securities many times a day before it will leave substantial amounts idle overnight. However, most large firms hold more cash than cash balance models imply, suggesting that managers disagree with this logic. Here are some possible reasons: 1 Firms have cash in the bank as a compensating balance in payment for banking services. 2 Large corporations have thousands of accounts with several dozen banks. Sometimes it makes more sense to leave cash alone than to manage each account daily. 27.3 Managing the Collection and Disbursement of Cash A firm’s cash balance as reported in its financial statements (book cash or ledger cash) is not the same thing as the balance shown in its bank account (bank cash or collected bank cash). The difference between bank cash and book cash is called float and represents the net effect of cheques in the process of collection. ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 751 6/11/09 10:13:56 AM 752 ___ EXAMPLE Chapter 27 Cash Management Float 27.2 Imagine that Great Mechanics International plc (GMI) currently has £100,000 on deposit with its bank. It purchases some raw materials, paying its vendors with a cheque written on 8 July for £100,000. The company’s books (that is, ledger balances) are changed to show the £100,000 reduction in the cash balance. But the firm’s bank will not find out about this cheque until it has been deposited at the vendor’s bank and has been presented to the firm’s bank for payment on, say, 15 July. Until the cheque’s presentation, the firm’s bank cash is greater than its book cash, and it has positive float. Position prior to 8 July: Float = Firm’s bank cash − Firm’s book cash = £100,000 − £100,000 =0 Position from 8 July to 14 July: Disbursement float = Firm’s bank cash − Firm’s book cash = £100,000 − 0 = £100,000 While the cheque is clearing, GMI has a balance with the bank of £100,000 and can obtain the benefit of this cash. For example, the bank cash could be invested in marketable securities. Cheques written by the firm generate disbursement float, causing an immediate decrease in book cash but no immediate change in bank cash. EXAMPLE More Float 27.3 Imagine that GMI receives a cheque from a customer for £100,000. Assume, as before, that the company has £100,000 deposited at its bank and has a neutral float position. It deposits the cheque and increases its book cash by £100,000 on 8 November. However, the cash is not available to GMI until its bank has presented the cheque to the customer’s bank and received £100,000 on, say, 15 November. In the meantime, the cash position at GMI will reflect a collection float of £100,000. Position prior to 8 November: Float = Firm’s bank cash − Firm’s book cash = £100,000 − £100,000 =0 Position from 8 November to 14 November: Collection float = Firm’s bank cash − Firm’s book cash = £100,000 − £200,000 = −£100,000 Cheques received by the firm represent collection float, which increases book cash immediately but does not immediately change bank cash. The firm is helped by disbursement float and is hurt by collection float. The sum of disbursement float and collection float is net float. A firm should be concerned more with net float and bank cash than with book cash. If a financial manager knows that a cheque will not clear for several days, he or she will be able ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 752 6/11/09 10:13:57 AM Managing the Collection and Disbursement of Cash 753 ___ to keep a lower cash balance at the bank than might be true otherwise. Good float management can generate a great deal of money. For example, suppose the average daily sales of the power distribution firm Schneider Electric SA are about $400 million. If Schneider Electric speeds up the collection process or slows down the disbursement process by one day, it frees up $400 million, which can be invested in marketable securities. With an interest rate of 4 per cent, this represents overnight interest of approximately $44,000 [= ($400 million/365) × 0.04]. Float management involves controlling the collection and disbursement of cash. The objective in cash collection is to reduce the lag between the time customers pay their bills and the time the cheques are collected. The objective in cash disbursement is to slow down payments, thereby increasing the time between when cheques are written and when cheques are presented. In other words, collect early and pay late. Of course, to the extent that the firm succeeds in doing this, the customers and suppliers lose money, and the trade-off is the effect on the firm’s relationship with them. Collection float can be broken down into three parts: mail float, in-house processing float, and availability float: EXAMPLE 27.4 1 Mail float is the part of the collection and disbursement process where cheques are trapped in the postal system. 2 In-house processing float is the time it takes the receiver of a cheque to process the payment and deposit it in a bank for collection. 3 Availability float refers to the time required to clear a cheque through the banking system. The clearing process takes place using the central clearing system of the country in which the bank operates (e.g. the Central Exchange in the UK), clearing banks, or local clearing houses. Float A cheque for £1,000 is mailed from a customer on Monday 1 September. Because of mail, processing and clearing delays it is not credited as available cash in the firm’s bank until the following Monday, seven days later. The float for this cheque is Float = £1,000 × 7 days = £7,000 Another cheque for £7,000 is mailed on 1 September. It is available on the next day. The float for this cheque is Float = £7,000 × 1 day = £7,000 The measurement of float depends on the time lag and the amount of money involved. The cost of float is an opportunity cost: the cash is unavailable for use while cheques are tied up in the collection process. The cost of float can be determined by: (a) estimating the average daily receipts; (b) calculating the average delay in obtaining the receipts; and (c) discounting the average daily receipts by the delayadjusted cost of capital. EXAMPLE 27.5 Average Float Suppose that Concepts Ltd has two receipts each month: Amount (£) Number of days’ delay Float (£) 5,000,000 ×3= 15,000,000 Item 2 3,000,000 ×5= 15,000,000 Total 8,000,000 Item 1 Here is the average daily float over the month: 30,000,000 ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 753 6/11/09 10:13:58 AM 754 ___ Chapter 27 Cash Management Average daily float: Total float £30,000,000 = Total days 30 = £1,000,000 Another procedure we can use to calculate average daily float is to determine average daily receipts and multiply by the average daily delay: Average daily receipts: Total receipts £8,000,000 = Total days 30 = £266,666.67 Weighted average delay = (5/8) × 3 + (3/8) × 5 = 1.875 + 1.875 = 3.75 days Average daily float = Average daily receipts × Weighted average delay = £266,666.67 × 3.75 = £1,000,000 EXAMPLE 27.6 Cost of Float Suppose Concepts Ltd has average daily receipts of £266,667. The float results in this amount being delayed 3.75 days. The present value of the delayed cash flow is V = £266,667 1 + RB where RB is the cost of debt capital for Concepts, adjusted to the relevant time frame. Suppose the annual cost of debt capital is 10 per cent. Then: RB = 0.1 × (3.75/365) = 0.00103 and £266,667 1 + 0.00103 = £266,392.62 V = Thus the net present value of the delay float is £266,392.62 − £266,667 = −£274.38 per day. For a year, this is −£274.38 × 365 = −£100,148.70. Accelerating Collections The following is a depiction of the basic parts of the cash collection process: Customer mails payment Time ___ Company receives payment Company deposits payment Cash received Mail delay Processing delay Clearing delay Mail float Processing float Clearing float Collection float Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 754 6/11/09 10:14:00 AM Managing the Collection and Disbursement of Cash 755 ___ The total time in this process is made up of mailing time, cheque processing time, and cheque clearing time. The amount of time cash spends in each part of the cash collection process depends on where the firm’s customers and banks are located, and how efficient the firm is at collecting cash. Some of the techniques used to accelerate collections and reduce collection time are lockboxes, concentration banking, and wire transfers. Lockboxes The lockbox is the most widely used device in the US to speed up collections of cash. It is a special post office box set up to intercept trade receivables payments. In Europe it is generally not used, and other methods are substantially more commonplace. The collection process is started by customers mailing their cheques to a post office box instead of sending them to the firm. The lockbox is maintained by a local bank, and is typically located no more than several hundred miles away. In the typical lockbox system the local bank collects the lockbox cheques from the post office several times a day. The bank deposits the cheques directly to the firm’s account. Details of the operation are recorded (in some computer-usable form) and sent to the firm. A lockbox system reduces mailing time, because cheques are received at a nearby post office instead of at corporate headquarters. Lockboxes also reduce the firm’s processing time, because they reduce the time required for a corporation to physically handle receivables and to deposit cheques for collection. A bank lockbox should enable a firm to get its receipts processed, deposited and cleared faster than if it were to receive cheques at its headquarters and deliver them itself to the bank for deposit and clearing. Concentration Banking Another way to speed up collection is to get the cash from the bank branches to the firm’s main bank more quickly. This is done by a method called concentration banking. With a concentration banking system the firm’s sales offices are usually responsible for collecting and processing customer cheques. The sales office deposits the cheques into a local deposit bank account. Surplus funds are transferred from the deposit bank to the concentration bank. The purpose of concentration banking is to obtain customer cheques from nearby receiving locations. Concentration banking reduces mailing time, because the firm’s sales office is usually nearer than corporate headquarters to the customer. Furthermore, bank clearing time will be reduced because the customer’s cheque is usually drawn on a local bank. Figure 27.4 illustrates this process, where concentration banks are combined with lockboxes in a total cash management system. The corporate cash manager uses the pools of cash at the concentration bank for short-term investing or for some other purpose. The concentration banks usually serve as the source of short-term investments. They also serve as the focal point for transferring funds to disbursement banks. Wire Transfers Wire transfers are the most common method of transferring cash in Europe. After the customers’ cheques get into the local banking network, the objective is to transfer the surplus funds (funds in excess of required compensating balances) from the local branch to the concentration bank. The fastest and most expensive way is by wire transfer. Wire transfers take only a few minutes, and the cash becomes available to the firm upon receipt of a wire notice at the concentration bank. Wire transfers take place electronically, from one computer to another, and eliminate the mailing and cheque clearing times associated with other cash transfer methods. The main wire service is SWIFT, operated by the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication. Delaying Disbursements Accelerating collections is one method of cash management; paying more slowly is another. The cash disbursement process is illustrated in Fig. 27.5. Techniques to slow down disbursement will attempt to increase mail time and cheque clearing time. ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 755 6/11/09 10:14:00 AM ___ 756 Chapter 27 Cash Management FIGURE 27.4 Corporate customers Corporate customers Firm sales office Statements are sent by mail to firm for receivables processing. Corporate customers Local bank deposits Post office lockbox receipts Funds are transferred to concentration bank by depository checks and wire transfers. Corporate customers Concentration bank Cash manager analyses bank balance and deposit internation and revises cash allocation. Firm cash manager Maintenance of cash reserves Disbursements Short-term investments of cash Maintenance of compensating balance at creditor bank Figure 27.4 Lockboxes and concentration banks in a cash management system Disbursement Float (‘Playing the Float Game’) Even though the cash balance at the bank may be $1 million, a firm’s books may show only $500,000 because it has written $500,000 in payment cheques. The disbursement float of $500,000 is available for the corporation to use until the cheques are presented for payment. Float in terms of slowing down payment cheques comes from mail delivery, cheque processing time, and collection of funds. This is illustrated in Fig. 27.5. Disbursement float can be increased by writing a cheque on a geographically distant bank. For example, a British supplier might be paid with cheques drawn on an Italian bank. This will increase the time required for the cheques to clear through the banking system. Zero-Balance Accounts Some firms set up a zero-balance account (ZBA) to handle disbursement activity. The account has a zero balance as cheques are written. As cheques are presented to the zero-balance account for payment (causing a negative balance), funds are automatically transferred in from a central control account. The master account and the ZBA are located in the same bank. Thus the transfer is automatic and involves only an accounting entry in the bank. Drafts Firms sometimes use drafts instead of cheques. Drafts differ from cheques because they are drawn not on a bank but on the issuer (the firm) and are payable by the issuer. The bank acts only as an agent, presenting the draft to the issuer for payment. When a draft is transmitted to a firm’s bank for collection, the bank must present the draft to the issuing firm for ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 756 6/11/09 10:14:04 AM Managing the Collection and Disbursement of Cash FIGURE 27.5 757 ___ Disbursement process Firm prepares cheque to supplier. Delivery of cheque to supplier. Deposit goes to supplier’s bank. Devices to delay cheque clearing 1. Write cheque on distant bank. 2. Hold payment for several days after postmarked in office. 3. Call supplier firm to verify statement accuracy for large amounts. Bank collects funds. Figure 27.5 Cash disbursement acceptance before making payment. After the draft has been accepted, the firm must deposit the necessary cash to cover the payment. The use of drafts rather than cheques allows a firm to keep lower cash balances in its disbursement accounts, because cash does not need to be deposited until the drafts are presented for payment. Ethical and Legal Questions The cash manager must work with cash balances collected by the bank and not the firm’s book balance, which reflects cheques that have been deposited but not collected. If not, a cash manager could be drawing on uncollected cash as a source for making short-term investments. Most banks charge a penalty for use of uncollected funds. However, banks may not have good enough accounting and control procedures to be fully aware of the use of uncollected funds. This raises some ethical and legal questions for the firm. Electronic Data Interchange and the Single Euro Payments Area: The End of Float? Electronic data interchange (EDI) is a general term that refers to the growing practice of direct electronic information exchange between all types of business. One important use of EDI, often called financial EDI, or FEDI, is to transfer financial information and funds electronically between parties, thereby eliminating paper invoices, paper cheques, mailing and handling. For example, it is possible to arrange to have your cheque account directly debited each month to pay many types of bill, and corporations now routinely directly deposit pay cheques into employee accounts. More generally, EDI allows a seller to send a bill electronically to a buyer, thereby avoiding the mail. The buyer can then authorize payment, which also occurs electronically. Its bank then transfers the funds to the seller’s account at a different bank. The net effect is that the length of time required to initiate and complete a business transaction is shortened considerably, and much of what we normally think of as float is sharply reduced or eliminated. As the use of FEDI increases (which it will), float management will evolve to focus much more on issues surrounding computerized information exchange and fund transfers. The Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA) is an attempt to reduce payment times across most countries in Europe. The initiative aims to harmonize payments across Europe by treating the different countries within the region as a single area. As a result, the payment system in Europe will be akin to a domestic market, and clearing times will be improved accordingly. The process towards full SEPA adoption began in January 2007, when all banks in Europe agreed to use an IBAN (International Bank Account Number) to identify transactions. The forms of payment affected by SEPA are credit transfers, direct debits, and credit and debit card payments. Full adoption of SEPA is expected by the end of 2010. ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 757 6/11/09 10:14:07 AM ___ 758 Chapter 27 Cash Management 27.4 Investing Idle Cash If a firm has a temporary cash surplus, it can invest in short-term marketable securities. The market for short-term financial assets is called the money market. The maturity of short-term financial assets that trade in the money market is one year or less. Most large firms manage their own short-term financial assets, transacting through banks and dealers. Some large firms and many small firms use money market funds. These are funds that invest in short-term financial assets for a management fee. The management fee is compensation for the professional expertise and diversification provided by the fund manager. Among the many money market mutual funds, some specialize in corporate customers. Banks also offer sweep accounts, where the bank takes all excess available funds at the close of each business day and invests them for the firm. Firms have temporary cash surpluses for these reasons: to help finance seasonal or cyclical activities of the firm, to help finance planned expenditures of the firm, and to provide for unanticipated contingencies. Seasonal or Cyclical Activities Some firms have a predictable cash flow pattern. They have surplus cash flows during part of the year and deficit cash flows the rest of the year. For example, Toys ‘R’ Us, a retail toy firm, has a seasonal cash flow pattern influenced by holiday sales. Such a firm may buy marketable securities when surplus cash flows occur and sell marketable securities when deficits occur. Of course, bank loans are another short-term financing device. Figure 27.6 illustrates the use of bank loans and marketable securities to meet temporary financing needs. Planned Expenditures Firms frequently accumulate temporary investments in marketable securities to provide the cash for a plant construction programme, dividend payment, and other large expenditures. Thus firms may issue bonds and shares before the cash is needed, investing the proceeds in short-term marketable securities, and then selling the securities to finance the expenditures. The important characteristics of short-term marketable securities are their maturity, default risk, marketability and taxability. Maturity Maturity refers to the time period over which interest and principal payments are made. For a given change in the level of interest rates, the prices of longer-maturity securities 27.6 Total financing needs FIGURE Marketable securities Bank loans Short-term financing Long-term financing: Equity plus long-term debt 0 1 2 3 Time Time 1: A surplus cash flow exists. Seasonal demand for investing is low. The surplus cash flow is invested in short-term marketable securities. Time 2: A deficit cash flow exists. Seasonal demand for investing is high. The financial deficit is financed by selling marketable securities, and by bank borrowing. Figure 27.6 Seasonal cash demands ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 758 6/11/09 10:14:11 AM Investing Idle Cash 759 ___ will change more than those of shorter-maturity securities. As a consequence, firms that invest in long-maturity securities are accepting greater risk than firms that invest in securities with short-term maturities. This type of risk is usually called interest rate risk. Most firms limit their investments in marketable securities to those maturing in less than 90 days. Of course, the expected return on securities with short-term maturities is usually less than the expected return on securities with longer maturities. Default Risk Default risk refers to the probability that interest or principal will not be paid on the due date or in the promised amount. In previous chapters we observed that various financial reporting agencies, such as Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s, compile and publish ratings of various corporate and public securities. These ratings are connected to default risk. Of course, some securities have negligible default risk, such as Treasury bills. Given the purposes of investing idle corporate cash, firms typically avoid investing in marketable securities with significant default risk. Marketability Marketability refers to how easy it is to convert an asset to cash. Sometimes marketability is referred to as liquidity. It has two characteristics: 1 No price pressure effect: If an asset can be sold in large amounts without changing the market price, it is marketable. Price pressure effects are those that come about when the price of an asset must be lowered to facilitate the sale. 2 Time: If an asset can be sold quickly at the existing market price, it is marketable. In contrast, a Renoir painting or antique desk appraised at $1 million will probably sell for much less if the owner must sell on short notice. In general, marketability is the ability to sell an asset for its face market value quickly and in large amounts. The most marketable of all securities are Treasury bills of developed countries. Taxability Several kinds of security have varying degrees of tax exemption: The interest on the bonds of governments tends to be exempt from taxes. Pre-tax expected returns on government bonds must be lower than on similar taxable investments, and therefore are more attractive to corporations in high marginal tax brackets. The market price of securities will reflect the total demand and supply of tax influences. The position of the firm may be different from that of the market. Different Types of Money Market Security Money market securities are generally highly marketable and short-term. They usually have low risk of default. They are issued by governments (Treasury bills, for example), domestic and foreign banks (certificates of deposit, for example), and business corporations (commercial paper, for example). Treasury bills are obligations of the government that mature in 90, 180, 270 or 360 days. They are pure discount securities. The 90-day and 180-day bills will be sold by auction every week, and 270-day and 360-day bills will be sold at longer intervals, such as every month. Treasury notes and bonds have original maturities of more than one year. They are interestbearing securities. The interest may be exempt from state and local taxes. Commercial paper refers to short-term securities issued by finance companies, banks and corporations. Commercial paper typically is unsecured. Maturities range from a few weeks to 270 days. There is no active secondary market in commercial paper. As a consequence, their marketability is low. (However, firms that issue commercial paper will directly repurchase before maturity.) The default risk of commercial paper depends on the financial strength of the issuer. Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s publish quality ratings for commercial paper. Certificates of deposit (CDs) are short-term loans to commercial banks. There are active markets in CDs of 3-month, 6-month, 9-month and 12-month maturities. Repurchase agreements are sales of government securities (for example, Treasury bills) by a bank or securities dealer with an agreement to repurchase. An investor typically buys some Treasury securities from a bond dealer and simultaneously agrees to sell them back at a later ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 759 6/11/09 10:14:11 AM ___ 760 Chapter 27 Cash Management date at a specified higher price. Repurchase agreements are usually very short-term – overnight to a few days. Eurodollar CDs are deposits of cash with foreign banks. Banker’s acceptances are time drafts (orders to pay) issued by a business firm (usually an importer) that have been accepted by a bank that guarantees payment. Summary and Conclusions The chapter discussed how firms manage cash. 1 A firm holds cash to conduct transactions and to compensate banks for the various services they render. 2 The optimal amount of cash for a firm to hold depends on the opportunity cost of holding cash and the uncertainty of future cash inflows and outflows. The Baumol model and the Miller–Orr model are two transaction models that provide rough guidelines for determining the optimal cash position. 3 The firm can use a variety of procedures to manage the collection and disbursement of cash to speed up the collection of cash and slow down payments. Some methods to speed collection are lockboxes, concentration banking and wire transfers. The financial manager must always work with collected company cash balances and not with the company’s book balance. To do otherwise is to use the bank’s cash without the bank knowing it, raising ethical and legal questions. 4 Because of seasonal and cyclical activities, to help finance planned expenditures, or as a reserve for unanticipated needs, firms temporarily find themselves with cash surpluses. The money market offers a variety of possible vehicles for parking this idle cash. Questions and Problems CONCEPT 1–4 1 Reasons for Holding Cash Is it possible for a firm to have too much cash? Why would shareholders care if a firm accumulates large amounts of cash? 2 Determining the Target Cash Balance Show, using both the Baumol model and the Miller–Orr model, how a firm can determine its optimal cash balance. 3 Collection and Disbursement of Cash Which would a firm prefer: a net collection float or a net disbursement float? Why? 4 Investing Idle Cash What options are available to a firm if it believes it has too much cash? How about too little? REGULAR 5–32 5 Agency Issues Are shareholders and creditors likely to agree on how much cash a firm should keep on hand? 6 Cash Management versus Liquidity Management What is the difference between cash management and liquidity management? 7 Short-Term Investments Why are preference shares with a dividend tied to short-term interest rates an attractive short-term investment for corporations with excess cash? 8 Float Suppose a firm has a book balance of $2 million. At the automatic teller machine (ATM) the cash manager finds out that the bank balance is $2.5 million. What is the situation here? If this is an ongoing situation, what ethical dilemma arises? 9 Short-Term Investments For each of the short-term marketable securities given here, provide an example of the potential disadvantages the investment has for meeting a corporation’s cash management goals: ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 760 6/11/09 10:14:12 AM Questions and Problems 761 ___ (a) Treasury bills. (b) Preference shares. (c) Negotiable certificates of deposit (NCDs). (d) Commercial paper. (e) Revenue anticipation notes. (f) Repurchase agreements. 10 Agency Issues It is sometimes argued that excess cash held by a firm can aggravate agency problems (discussed in Chapter 1) and, more generally, reduce incentives for shareholder wealth maximization. How would you frame the issue here? 11 Use of Excess Cash One option a firm usually has with any excess cash is to pay its suppliers more quickly. What are the advantages and disadvantages of this use of excess cash? 12 Use of Excess Cash Another option usually available is to reduce the firm’s outstanding debt. What are the advantages and disadvantages of this use of excess cash? 13 Float An unfortunately common practice goes like this (warning – don’t try this at home). Suppose you are out of money in your bank current account; however, your local grocery store will, as a convenience to you as a customer, cash a cheque for you. So you cash a cheque for £200. Of course, this cheque will bounce unless you do something. To prevent this, you go to the grocery the next day and cash another cheque for £200. You take this £200 and deposit it. You repeat this process every day, and in doing so you make sure that no cheques bounce. Eventually, manna from heaven arrives (perhaps in the form of money from home), and you are able to cover your outstanding cheques. To make it interesting, suppose you are absolutely certain that no cheques will bounce along the way. Assuming this is true, and ignoring any question of legality (what we have described is probably illegal cheque-kiting), is there anything unethical about this? If you say yes, then why? In particular, who is harmed? 14 Interpreting Miller–Orr Based on the Miller–Orr model, describe what will happen to the lower limit, the upper limit, and the spread (the distance between the two) if the variation in net cash flow grows. Give an intuitive explanation for why this happens. What happens if the variance drops to zero? 15 Changes in Target Cash Balances Indicate the likely impact of each of the following on a company’s target cash balance. Use the letter I to denote an increase and D to denote a decrease. Briefly explain your reasoning in each case. (a) Commissions charged by brokers decrease. (b) Interest rates paid on money market securities rise. (c) The compensating balance requirement of a bank is raised. (d) The firm’s credit rating improves. (e) The cost of borrowing increases. (f) Direct fees for banking services are established. 16 Using the Baumol Model Given the following information, calculate the target cash balance using the Baumol model: Annual interest rate: 7% Fixed order cost: $10 Total cash needed: $5,000 How do you interpret your answer? 17 Opportunity versus Trading Costs White Whale NV has an average daily cash balance of $400. Total cash needed for the year is $25,000. The interest rate is 5 per cent, and replenishing the cash costs $6 each time. What are the opportunity cost of holding cash, the trading cost, and the total cost? What do you think of White Whale’s strategy? ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 761 6/11/09 10:14:12 AM ___ 762 Chapter 27 Cash Management 18 Costs and the Baumol Model D&C Accountants needs a total of £4,000 in cash during the year for transactions and other purposes. Whenever cash runs low, the firm sells off £300 in securities and transfers the cash in. The interest rate is 6 per cent per year, and selling off securities costs £25 per sale. (a) What is the opportunity cost under the current policy? The trading cost? With no additional calculations, would you say that D&C keeps too much or too little cash? Explain. (b) What is the target cash balance derived using the Baumol model? 19 Calculating Net Float Each business day, on average, a company writes cheques totalling $25,000 to pay its suppliers. The usual clearing time for the cheques is four days. Meanwhile, the company is receiving payments from its customers each day, in the form of cheques, totalling $40,000. The cash from the payments is available to the firm after two days. (a) Calculate the company’s disbursement float, collection float, and net float. (b) How would your answer to part (a) change if the collected funds were available in one day instead of two? 20 Costs of Float Purple Feet Wine Ltd receives an average of £9,000 in cheques per day. The delay in clearing is typically four days. The current interest rate is 0.025 per cent per day. (a) What is the company’s float? (b) What is the most Purple Feet should be willing to pay today to eliminate its float entirely? (c) What is the highest daily fee the company should be willing to pay to eliminate its float entirely? 21 Float and Weighted Average Delay Every month your neighbour receives two cheques, one for $16,000 and one for $3,000. The larger cheque takes four days to clear after it is deposited; the smaller one takes five days. (a) What is the total float for the month? (b) What is the average daily float? (c) What are the average daily receipts and weighted average delay? 22 NPV and Collection Time Your firm has an average receipt size of £80. A bank has approached you concerning a new service that will decrease your total collection time by two days. You typically receive 12,000 cheques per day. The daily interest rate is 0.016 per cent. If the bank charges a fee of £190 per day, should the new service be accepted? What would the net annual savings be if the service were adopted? 23 Using Weighted Average Delay A mail-order firm processes 5,000 cheques per month. Of these, 65 per cent are for $50 and 35 per cent are for $70. The $50 cheques are delayed two days on average; the $70 cheques are delayed three days on average. (a) What is the average daily collection float? How do you interpret your answer? (b) What is the weighted average delay? Use the result to calculate the average daily float. (c) How much should the firm be willing to pay to eliminate the float? (d) If the interest rate is 7 per cent per year, calculate the daily cost of the float. (e) How much should the firm be willing to pay to reduce the weighted average float by 1.5 days? 24 Value of Lockboxes Paper Submarine Manufacturing is investigating a lockbox system to reduce its collection time. It has determined the following: ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 762 6/11/09 10:14:13 AM Questions and Problems 763 ___ Average number of payments per day: 400 Average value of payment: £1,400 Variable lockbox fee (per transaction): £0.75 Daily interest rate on money market securities: 0.02% The total collection time will be reduced by three days if the lockbox system is adopted. (a) What is the PV of adopting the system? (b) What is the NPV of adopting the system? (c) What is the net cash flow per day from adopting? Per cheque? 25 Collections It takes Modular Homes AB about six days to receive and deposit cheques from customers. Modular Homes’ management is considering a new system to reduce the firm’s collection times. It is expected that the new system will reduce receipt and deposit times to three days total. Average daily collections are NKr140,000, and the required rate of return is 9 per cent per year. (a) What is the reduction in outstanding cash balances as a result of implementing the new system? (b) What monetary return could be earned on these savings? (c) What is the maximum monthly charge Modular Homes should pay for this new system? 26 Value of Delay No More Pencils plc disburses cheques every two weeks that average £70,000 and take seven days to clear. How much interest can the company earn annually if it delays transfer of funds from an interest-bearing account that pays 0.02 per cent per day for these seven days? Ignore the effects of compounding interest. 27 NPV and Reducing Float No More Books SA has an agreement with National Bank whereby the bank handles $8 million in collections a day and requires a $500,000 compensating balance. No More Books is contemplating cancelling the agreement and dividing its Belgian activities so that two other banks will handle its business. Banks A and B will each handle $4 million of collections a day, and each requires a compensating balance of $300,000. No More Books’ financial management expects that collections will be accelerated by one day if the Belgian activities are divided between two banks. Should the company proceed with the new system? What will be the annual net savings? Assume that the T-bill rate is 5 per cent annually. 28 Determining Optimal Cash Balances The Tommy Byrne Company is currently holding $700,000 in cash. It projects that over the next year its cash outflows will exceed cash inflows by $360,000 per month. How much of the current cash holding should be retained, and how much should be used to increase the company’s holdings of marketable securities? Each time these securities are bought or sold through a broker, the company pays a fee of $500. The annual interest rate on money market securities is 6.5 per cent. After the initial investment of excess cash, how many times during the next 12 months will securities be sold? 29 Using Miller–Orr SlapShot plc has a fixed cost associated with buying and selling marketable securities of £100. The interest rate is currently 0.021 per cent per day, and the firm has estimated that the standard deviation of its daily net cash flows is £75. Management has set a lower limit of £1,100 on cash holdings. Calculate the target cash balance and upper limit using the Miller–Orr model. Describe how the system will work. 30 Using Miller–Orr The variance of the daily cash flows for the Pele Bicycle Shop is $960,000. The opportunity cost to the firm of holding cash is 7 per cent per year. What should be the target cash level and the upper limit if the tolerable lower limit has been established as $150,000? The fixed cost of buying and selling securities is $500 per transaction. ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 763 6/11/09 10:14:13 AM ___ 764 Chapter 27 Cash Management 31 Using Baumol All Night Ltd has determined that its target cash balance if it uses the Baumol model is $2,200. The total cash needed for the year is $21,000, and the order cost is $10. What interest rate must All Night be using? 32 Lockboxes and Collection Time Bird’s Eye Treehouses Ltd, a Scottish company, has determined that a majority of its customers are located in the Highlands area. It therefore is considering using a lockbox system offered by a bank located in Inverness. The bank has estimated that use of the system will reduce collection time by two days. Based on the following information, should the lockbox system be adopted? Average number of payments per day: 600 Average value of payment: £1,100 Variable lockbox fee (per transaction): £0.35 Annual interest rate on money market securities: 6.0% How would your answer change if there were a fixed charge of £1,000 per year in addition to the variable charge? CHALLENGE 33–35 33 Calculating Transactions Required Leon Dung SA, a large fertilizer distributor based in the north of Spain, is planning to use a lockbox system to speed up collections from its customers located in the Castille y Leon region. A Vallidolid-area bank will provide this service for an annual fee of $25,000 plus 10 cents per transaction. The estimated reduction in collection and processing time is one day. If the average customer payment in this region is $5,500, how many customers each day, on average, are needed to make the system profitable for Leon Dung? Treasury bills are currently yielding 5 per cent per year. 34 Baumol Model Lisa Tylor, CFO of Purple Rain Co., concluded from the Baumol model that the optimal cash balance for the firm is $10 million. The annual interest rate on marketable securities is 5.8 per cent. The fixed cost of selling securities to replenish cash is $5,000. Purple Rain’s cash flow pattern is well approximated by the Baumol model. What can you infer about Purple Rain’s average weekly cash disbursement? 35 Miller–Orr Model Gold Star Ltd and Silver Star Ltd both manage their cash flows according to the Miller–Orr model. Gold Star’s daily cash flow is controlled between £95,000 and £205,000, whereas Silver Star’s daily cash flow is controlled between £120,000 and £230,000. The annual interest rates Gold Star and Silver Star can get are 5.8 per cent and 6.1 per cent, respectively, and the costs per transaction of trading securities are £2,800 and £2,500, respectively. (a) What are their respective target cash balances? (b) Which firm’s daily cash flow is more volatile? M I N I CA S E ___ Cash Management at Seglem Ltd Seglem Ltd was founded 20 years ago by its president, Trygve Seglem. The company originally began as a mail-order company but has grown rapidly in recent years, in large part thanks to its website. Because of the wide geographical dispersion of the company’s customers, it currently employs a lockbox system with collection centres in Trondheim, Stavanger, Hammerfest, Molde and Tromsø. Arne Austreid, the company’s treasurer, has been examining the current cash collection policies. On average, each lockbox centre handles NKr130,000 in payments each day. The company’s current policy is to invest these payments in short-term marketable securities daily at the collection centre banks. Every two weeks the investment accounts are swept, and the proceeds are wire-transferred to Seglem’s headquarters in Oslo to meet the company’s payroll. The investment accounts each pay 0.015 per cent per day, and the wire transfers cost 0.15 per cent of the amount transferred. Arne has been approached by Third National Bank, located just outside Oslo, about the possibility of setting up a concentration banking system for Seglem Ltd. Third National Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 764 6/11/09 10:14:14 AM Endnotes 765 ___ will accept the lockbox centres’ daily payments via automated clearing house (ACH) transfers in lieu of wire transfers. The ACH-transferred funds will not be available for use for one day. Once cleared, the funds will be deposited in a short-term account, which will also yield 0.015 per cent per day. Each ACH transfer will cost NKr700. Trygve has asked Arne to determine which cash management system will be the best for the company. Arne has asked you, his assistant, to answer the following questions: 1 What is Seglem’s total net cash flow from the current lockbox system available to meet payroll? 2 Under the terms outlined by Third National Bank, should the company proceed with the concentration banking system? 3 What cost of ACH transfers would make the company indifferent between the two systems? Additional Reading The following papers consider the cash management function in firms. Almeida, H., M. Campello and M.S. Weisbach (2004) ‘The cash flow sensitivity of cash’, Journal of Finance, vol. 59, no. 4, pp. 1777–1804. US. Bates, T.W., K.M. Kahle and R.M. Stulz (2009) ‘Why do US firms hold so much more cash than they used to?’, Journal of Finance (forthcoming). US. Dittmar, A. and J. Mahrt-Smith (2007) ‘Corporate governance and the value of cash holdings’, Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 83, no. 3, pp. 599–634. US. Foley, C.F., J.C. Hartzell, S. Titman and G. Twite (2007) ‘Why do firms hold so much cash? A tax based explanation’, Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 86, no. 4, pp. 579–607. US. Kalcheva, I. and K.V. Lins (2007) ‘International evidence on cash holdings and expected managerial agency problems’, Review of Financial Studies, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 1087–1112. International. Klasa, S., W.F. Maxwell and H. Ortiz-Molina (2009) ‘The strategic use of corporate cash holdings in collective bargaining with labor unions’, Journal of Financial Economics (forthcoming). US. Pinkowitz, L., R. Stulz and R. Williamson (2007) ‘Cash holdings, dividend policy, and corporate governance: a cross-country analysis’, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 81– 87. International. Endnotes 1 W.S. Baumol, ‘The transactions demand for cash: an inventory theoretic approach’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 66 (November 1952). 2 M.H. Miller and D. Orr, ‘A model of the demand for money by firms’, Quarterly Journal of Economics (August 1966). 3 D. Mullins and R. Hamonoff discuss tests of the Miller–Orr model in ‘Applications of inventory cash management models’, in Modern Developments in Financial Management, ed. by S. C. Myers (New York: Praeger, 1976). They show that the model works very well when compared with the actual cash balances of several firms. However, simple rules of thumb do as good a job as the Miller–Orr model. To help you grasp the key concepts of this chapter check out the extra resources posted on the Online Learning Centre at www.mcgraw-hill.co.uk/textbooks/hillier Among other helpful resources there are PowerPoint presentations, chapter outlines and mini-cases. ___ Finanza aziendale Stephen Ross, David Hillier, Randolph Westerfield, Jeffrey Jaffe, Bradford Jordan © 2012 McGraw-Hill Ross_ch27.indd 765 6/11/09 10:14:15 AM