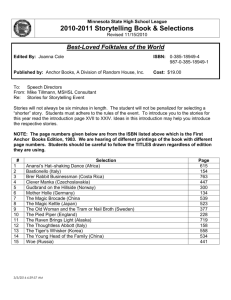

Anchor Institutions

advertisement