Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease - American Orthopaedic Foot and

advertisement

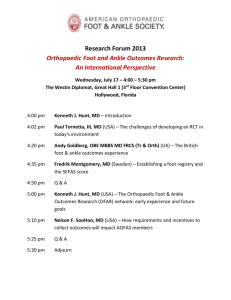

OrthopaedicsOne Articles 17 Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Contents Introduction Anatomy and Biomechanics Clinical Presentation Pathogenesis Diagnosis Physical Examination Imaging Conservative Treatment Operative Treatment References 17.1 Introduction Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) — also known as Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy, hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy (HMSN), hereditary sensorimotor neuropathy (HSMN), and peroneal muscular atrophy — is the most common inherited neuropathy, affecting roughly 1 in 2,500 persons.[1] The disease is names after Jean-Martin Charcot, Pierre Marie, and Howard Henry Tooth, the physicians who first described the disease in 1886.[2] Patient life expectancy is normal. Males are affected more frequently, but affected females have more severe symptoms. Disease pathology stems primarily from an abnormality in the peripheral nervous system, with degenerative changes in the motor nerve roots. CMT is incurable and characterized by loss of muscle and touch sensation, predominantly in the legs and feet but also commonly in the arms and hands in more advanced stages of the disease. 17.2 Anatomy and Biomechanics CMT is classically characterized by agonist-antagonist muscle pairings. A cavovarus foot is classically described, in which the stronger peroneus longus and tibial posterior muscles cause a hindfoot varus and forefoot valgus position. There are two primary factors that contribute to the development of a hindfoot varus deformity seen in CMT. As a result of forefoot valgus and a plantar flexed first ray, the hindfoot assumes a compensatory varus position, thus overloading the lateral border of the foot and causing ankle instability and peroneal tendinitis. Hindfoot varus further progresses as the weakened peroneus brevis cannot continue to oppose the posterior tibialis on the opposite side.[3] This progression can lead to degenerative arthritic changes. Page 116 of 372 OrthopaedicsOne Articles An elevated arch (pes cavus) develops in CMT due to tightening of the Windlass mechanism in which the plantar fascia is overly tense, resulting in elevation of the longitudinal arch and shortening of the foot. Pes cavus is a result of the imbalance between weak intrinsic and extrinsic muscles in the foot due to motor neuropathy in CMT. Clawing of the toes develops due to a similar loss of intrinsic muscle strength and coordination. There is combined hyperextension at the metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ) and plantar flexion at the interphalangeal joint (IPJ). Due to the motor and sensory neuropathy of CMT, the long toe extensors are recruited to assist with weakened ankle dorsiflexion, thus worsening the hyperextension deformity at the MTPJ.[3] Meanwhile, the long toe flexors remain intact and cause flexion deformity at the IPJ. Lastly, ankle equinus and instability are commonly seen in CMT due to the unopposed tension of the gastrocnemius-soleus complex against a weakened tibialis anterior. 17.3 Clinical Presentation Patients with CMT typically present in adolescence and early adulthood; however, some patients have no apparent symptoms until the third or fourth decade of life. The most common presenting symptom is pain and peripheral neuropathy, consisting of foot drop early in the disease accompanied by a high arch and clawing of the toes. Pain is typically due to increased load on an isolated portion of the foot such as the lateral border, first metatarsal head, or lateral metatarsal head.[4] Lateral ankle pain may develop as a result of hindfoot varus, causing ankle instability and increased strain of the lateral collateral ligaments. Lower extremity muscle wasting is often associated with CMT, and in advanced cases of the disease, weakness and atrophy are noticeable in the arms and hands. The clinical picture of CMT can vary widely depending on the level of disease, but it generally progresses in a distal to proximal direction. Patients with CMT can experience decrements in hearing; vision; neck and shoulder strength; and breathing, speaking, and swallowing as vocal cords may atrophy substantially. Baseline tremors may be present. Neuropathic pain is a common symptom of CMT similar to the pain associated with complex regional pain syndrome and post-herpetic neuralgia, but the degree and magnitude of pain are highly dependent on the individual patient [5]. 17.4 Pathogenesis CMT is caused by mutations in neuronal proteins that affect the myelin nerve sheath and occasionally the nerve axon itself. Duplication of a large region of chromosome 17p12, including the genes PMP22 and MFN2 occurs in approximately 80% of cases of CMT. These genes encode for vital mitochondrial proteins that migrate down axons in peripheral nerves. Mutations in these proteins cause protein aggregation that prevents their ability to travel down axons towards synapses, thus disabling synaptic function.[6] Mutations in CMT may also affect Schwann cells, which are integral for proper myelin sheath function and the regulation of neuronal survival and differentiation.[7] Thus far, 39 different gene mutations have been recognized as causes of CMT, with subdivision of the disease into demyelinating and axonal pathologies. Transmission among the subgroups can be autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, and X-linked. 17.5 Diagnosis Page 117 of 372 OrthopaedicsOne Articles CMT can be clinically diagnosed through a comprehensive personal and family history along with physical examiantion, especially when classic characteristics of the disease are present, such as foot drop with toe clawing and a high foot arch. Diagnosis can also be made using electromyography, nerve biopsy, and DNA testing in difficult-to-diagnose cases or for disease confirmation. DNA testing may provide a definitive diagnosis, but not all markers for CMT are known. A consult with a neurologist and a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician are recommended to help manage the overall burden of disease. 17.6 Physical Examination Roughly 95% of patients with CMT have a foot deformity consisting of a high arch with clawed toes (Figure 1).[8] A plantar-flexed first ray is usually present, indicative of forefoot valgus due to the hypertrophied peroneus longus overpowering a weak tibialis anterior. Claw toes result from the long flexor and extensor tendons overpowering the lumbrical and interosseous muscles.[9] Other common foot and ankle symptoms include: Muscle cramping Difficulty with normal shoe wear Ankle instability Metatarsalgia On examination, motor strength testing should be particularly focused on the intrinsic muscles of the feet, as these are the first part of the foot affected in CMT. Progression of the disease goes on to next weaken the peroneus brevis and tibial anterior tendons. There is often gross muscle atrophy of the calf, with a resulting “stork leg” appearance and decreased ability to heel walk (Figure 2). Figure 1. Clinical appearance of CMT foot demonstrating classic findings of a cavovarus deformity with clawed toes. Page 118 of 372 OrthopaedicsOne Articles Figure 2. Clinical picture of CMT demonstrating common finding of gross lower extremity muscle atrophy with a resulting “stork leg” appearance. Examination should be performed during sitting, standing, and walking. Gait examination is important for planning potential tendon transfers to correct stance and swing-phase deficits. In patients with a secondary equinus contracture at the ankle from CMT, a high-stepping, drop-foot gait with hyperextension of the knee develops.[9] Sensory loss should be examined through deep tendon reflexes, as patients with CMT often have weak or absent patellar and Achilles reflexes. Sensory findings include dyesthesias and decreased light touch, vibratory, and proprioceptive senses. There is often callus formation under the metatarsal heads and lateral border of the foot as a result of the combined effects of decreased sensation and a cavovarus foot deformity. The plantar pad migrates distal to the metatarsal head, thus moving the thinner proximal skin under the weight-bearing portion of the metatarsal head. In the early stages of CMT, the presenting hindfoot varus deformity is flexible, as are any other associated deformities. Range of motion of all joints in the foot and ankle should be checked. A commonly employed test for hindfoot flexibility is the Coleman block test (Figure 3). In this test, the hindfoot and lateral forefoot are placed on a rigid block. If the hindfoot is able to correct to neutral or evert, the deformity is flexible and due to a plantar-flexed first ray. If the hindfoot cannot correct, the hindfoot is fixed and both the forefoot and hindfoot are involved in the deformity.[9] Figure 3. Coleman block test demonstrating correction of flexible hindfoot varus after a block is placed under the lateral side of the forefoot.[9] Page 119 of 372 OrthopaedicsOne Articles 17.7 Imaging Standard weight-bearing anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the foot and ankle should be taken in all patients with CMT. Radiographs of the foot typically demonstrate forefoot adduction, plantar flexion of the first ray, increased arch, and increased calcaneal inclination (Figure 4). Radiographs of the ankle commonly show external rotation of the tibia with hindfoot varus seen as a double density of the talar dome. Additional views of the foot, such as the Harris heel view and modified Cobey view, demonstrate hindfoot alignment. CT scans may be obtained if there is concern about possible stress fractures or degenerative changes within the foot and ankle. Figure 4. Lateral radiograph of CMT demonstrating plantar flexion of the first ray, increased arch, and increased calcaneal inclination. 17.8 Conservative Treatment Overall, there is no consensus on appropriate treatment for CMT, and the overarching goals are to: Reduce symptoms Maintain function Decrease pain Prevent progression of deformity Human trials have shown that high doses of ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) in patients with CMT may help decreased overall symptoms, but these results are mixed and not conclusive.[10] The most important treatment for CMT patients is to maintain, as best as possible, their current muscle strength, tone, flexibility, and range of motion. Page 120 of 372 OrthopaedicsOne Articles Physical activity is recommended, with a focus on strengthening and mobilization of weakened muscles with the assistance of a physiotherapist. CMT patients are often globally deconditioned and weak, therefore, cardiovascular exercise in addition to foot and ankle specific exercises are also recommended. Non-impact exercises such as biking and swimming are preferred to impact activities such as walking, hiking, and running, as these exercises can worsen the already weakened muscles and cause progression of deformity. Active stretching is also important to help prevent the development of fixed deformities. Bracing, using plastic molded or lace-up ankle-foot orthoses, is another important conservative treatment for foot drop and ankle instability associated with CMT.[11] Orthoses also help increase the weigh-bearing portion of the foot to better distribute load. Well-fitting footwear that does not cause excessive abrasion or worsen instability is critical, as CMT patients have difficulty finding shoes that can accommodate a high-arched foot with clawed toes. Shoes with an extra-deep toe box help accommodate the foot, although custom shoes are often needed. Shoe inserts and metatarsal pads can also be helpful in patients with flexible hindfoot deformities to elevate the heel and lateral forefoot. Patients with overload of the first metatarsal head may benefit from a first metatarsal head cutout rather than additional padding. Patients with an equinus deformity may require a night splint. 17.9 Operative Treatment In general, operative intervention should be delayed in patients with CMT until the deformities fail to respond to non-operative management and become painful, interfere with activities of daily living, or cause contractures. Surgical options are largely based upon whether the deformity is flexible or fixed. In cases of flexible, supple deformities, soft-tissue procedures alone are often adequate and are an early priority to help prevent further muscle imbalance and deformity progression. A number of options exist, including peroneus longus transfer to the peroneus brevis to help reduce the first ray plantar flexion and increase eversion strength to the foot and ankle.[12] Transfer of the posterior tibialis tendon to the dorsum of the foot through the interosseous membrane can be employed to reduce the varus position of the hindfoot and aid in ankle dorsiflexion. Transfer of the posterior tibialis to the cuboid has also been previously described and employed for varus correction. Cavus deformity can be addressed through release of the plantar fascia. In skeletally immature patients with flexible forefoot and hindfoot defomities, release and lengthening of the plantar fascia along with combined posterior tibialis transfer often are sufficient for correction. Flexible claw toes can be treated with transfer of the flexors to extensors (Girdlestone-Taylor procedure). Clawing of the hallux can be addressed with IPJ fusion and transfer of the extensor hallucis longus to the neck of the metatarsal (Jones procedure).[13] In cases of fixed deformities found in more advanced stages of the disease, bony osteotomy and fusion are often needed, along with soft-tissue procedures. However, muscle imbalances must be addressed to prevent recurrent deformity. CMT patients who can overcorrect into mild hindfoot valgus on Coleman block testing with a fixed first metatarsal cavus deformity can be treated with first metatarsal dorsiflexion osteotomy, plantar fascia release, and transfer of the peroneus longus to brevis.[13] Osteotomy fixation can be achieved using a four-hole one-quarter tubular plate and 2.7-mm or 3.5-mm cortical screws. Fixed hindfoot varus can be addressed with a closing wedge (Dwyer) or lateral displacement calcaneal osteotomy. The lateralizing calcaneal osteotomy helps correct foot position during heel strike and lateralizes the Achilles pull during toe-off. In cases of severe fixed deformities, triple arthrodesis remains the preferred operation, as bony resections are needed to correct the nature and number of deformities. Page 121 of 372 OrthopaedicsOne Articles After surgery, most patients will continue to need an orthotic device such as an ankle-foot orthosis to assist with a weakened tibialis anterior and foot drop. Despite the benefits obtained with corrective surgery, patients often experience progression of the disease, necessitating repeat surgical procedures. 17.10 References 1. Krajewski KM. Neurological dysfunction and axonal degeneration in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Brain 123(7): 1516--27, 2000. 2. Charcot JM, Marie P, and Tooth HH. Sur une forme particulière d'atrophie musculaire progressive, souvent familiale débutant par les pieds et les jambes et atteignant plus tard les mains", Revue médicale, Paris, 6: 97-138, 1886. 3. Richardson EG. The foot and ankle: Neurogenic disorders, in Canale ST [ed]: Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, ed 10. St. Louis, MO, Mosby, 2003 4. Alexander IJ and Johnson KA. Assessment and management of pes cavus in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Clinical Orthopedics 246:273-81, 1989. 5. Carter GT, Jensen MP, Galer BS, Kraft GH, Crabtree LD, Beardsley RM, Abresch RT, Bird TD. Neuropathic pain in Charcot-Marie-tooth disease. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 79(12): 1560--64, 1998. 6. Baloh RH, Schmidt RE, Pestronk A, Milbrandt J. Altered Axonal Mitochondrial Transport in the Pathogenesis of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease from Mitofusin 2 Mutations. Journal of Neuroscience 27(2): 422--30, 2007. 7. Berger P, Young P, Suter U. Molecular cell biology of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease". Neurogenetics 4(1): 1--15, 2002. 8. Nunley JA, Pfeffer GB, Sanders RW, Trepman E [eds]: Advanced Reconstruction: Foot and Ankle. Rosemont, IL, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, p 498, 2004. 9. Younger AS and Hansen ST: Adult cavovarus foot. Journal of the American Academy Orthopaedic Surgeons 13:302-315, 2005. 10. Clinical Trials - Neuromuscular Trial/Study. http://www.mda.org/research/view_ctrial.aspx?id=186. 11. Azmaipairashvili Z, Riddle EC, Scavina M, Kumar SJ. Correction of cavovarus foot deformity in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics 25:360-365, 2005. 12. Bruffey JD, Copp SN, Colwell CW. Surgical reconstruction of acquired spastic foot and ankle deformity. Foot and Ankle Clinics 5:381-416, 2000. 13. Hansen ST Jr [ed]: Functional Reconstruction of the Foot and Ankle. Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, p 369, 2000. Page 122 of 372