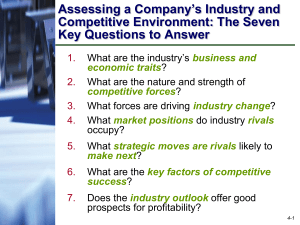

3 Evaluating a Company's External Environment

advertisement