African Higher Education: Opportunities for Transformative Change

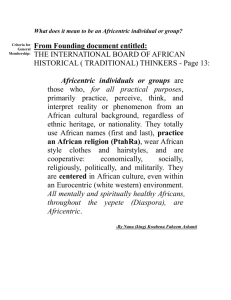

advertisement