C A S E S

I N

S T R A T E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A U D I T I N G

KPMG and University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Business Measurement Case Development and Research Program

Edited by

Timothy B. Bell

Director, Assurance Research,

Assurance & Advisory Services Center, KPMG LLP

Ira Solomon

R.C. Evans Endowed Chair in Commerce

Head, Department of Accountancy,

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Foreword by

D. Scott Showalter

National Managing Partner,

Assurance & Advisory Services Center, KPMG LLP

Visiting Executive Lecturer, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

©2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association.

All Rights Reserved. Printed in the U.S.A.

This book is not intended to constitute an exhaustive coverage of all the policies and procedures comprising

KPMG’s full audit process, and how it comports with generally accepted auditing standards.

TA B L E

O F

C O N T E N T S

Foreword

D. Scott Showalter

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . VII

Preface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . XI

The Strategic-Systems Approach to Auditing

Timothy B. Bell , Mark E. Peecher, and Ira Solomon . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

A Guide to Selecting SSA Cases

Timothy B. Bell , Mark E. Peecher, and Ira Solomon

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

CVS/Pharmacy: Growth Strategies in the Retail Drug Industry

Stephen Asare, Richard McGowan, Greg Trompeter, and

Arnold Wright . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

IDEC Pharmaceuticals Corporation

Shawn M. Davis and Ronald R. King . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

Lincoln Savings and Loan

Merle Erickson, Brian Mayhew, and William L. Felix, Jr.,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . 139

Loblaw Companies Ltd.

Royston Greenwood and Steve Salterio .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 165

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

TA B L E

O F

C O N T E N T S

Mercedes-Benz U.S. International

Brian Ballou, Richard Tabor, and Mustafa Uzumeri

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 211

Rieter Automotive North America, Inc.

Roger D. Martin, Fred Phillips, and Michael D. Shields

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 257

Trigon Healthcare, Inc.: Growth Through Acquisition in the

Hypercompetitive Managed Healthcare Environment

Anne York and Linda McDaniel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 289

Wells Fargo: Business-to-Business Electronic Commerce

George Foster, Mahendra Gupta, and Richard Palmer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 321

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 359

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

F O R E W O R D

If ever there were any doubts about the criticality of the financial statement

audit to the efficient functioning of the capital markets, recent events have

dispelled them. Truthful and credible financial and nonfinancial business

information empowers the capital supplier to assess decision-relevant states

of the business, and competition within the capital markets for the best

returns on investments leads ultimately to an efficient allocation of

resources within our market economy. Information that is not perceived by

users to be credible, even if it is truthful, will be disbelieved, causing a shift

of resources from their most productive uses to less productive ones. In the

final analysis, everyone is impacted negatively by widespread perceptions

that business information is not credible, whether through poor decision-

changing business environment. In addition, KPMG has a longstanding

tradition of sharing information about our audit innovations with the

academic community. By treating our audit approach as an open standard,

we foster further improvements and innovations as others contribute their

critical analysis, empirical validation, and new ideas. We pride ourselves on

openness and strive to achieve excellence and marketplace differentiation

B U S I N E S S

M E A S U R E M E N T

through superior audit execution and continuous innovation, not secrecy.

R E S E A R C H

approach so that efficient and effective audits are possible in an ever-

A N D

KPMG has a longstanding tradition of continuously innovating our audit

D E V E L O P M E N T

other ripple effects throughout the economy.

C A S E

and wants and new business development, inefficient labor markets, or

P R O G R A M

making about savings investments, mismatches between consumer needs

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

C A S E S

I N

S T R AT E G I C - SYS T E M S

A U D I T I N G

VII

F O R E W O R D

The quality of audits and the quality of audit education and research are

inextricably linked. High-quality scholarly research fosters learning by

educators and practitioners. Educators transfer new knowledge to students

who apply that knowledge upon entry into the profession.

professionals become tomorrow’s leaders and innovators.

These

They share

information on new innovations and other resources needed by researchers

to critically analyze and empirically validate new audit methods and

techniques and generate new ideas for further improvement.

These

interactions taken together form a self-reinforcing feedback loop

that fosters evolution of the profession so that its continued vitality

is ensured.

Consequently, leaders at KPMG have long understood

and auditing education, as well as support for scholarly research in these

areas, are strategic imperatives for the profession.

A recent example of our commitment to profession-wide learning is

distributing to the public the monograph entitled Auditing Organizations

Through a Strategic-Systems Lens: The KPMG Business Measurement

Measurement Case Development and Research Program. The monograph

demands placed on auditors when assessing the veracity of management’s

presents an overview of, and rationale for, recent audit innovations at

KPMG (and other firms) designed to help auditors better cope with an everincreasing level of business complexity and the related business-learning

assertions.

Following dissemination of the monograph, the case

development and research program was established to engage scholars in

the development of classroom materials relevant to a 21st century audit

environment, followed by scholarly research to advance knowledge and

enable further improvements in audit methods and techniques.

B U S I N E S S

M E A S U R E M E N T

D E V E L O P M E N T

Process and establishing the KPMG and University of Illinois Business

C A S E

A N D

R E S E A R C H

P R O G R A M

that proactive involvement in the continuous improvement of accounting

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

VIII

K P M G

A N D

U N I V E R S I T Y

O F

I L L I N O I S

AT

U R B A N A - C H A M PA I G N

F O R E W O R D

These projects were intentionally designed to be highly collaborative to

achieve significant synergies through the combination of complementary

talents and skills. Our goal was to produce some of the most realistic and

intellectually nurturing teaching materials available for business and

assurance education. We sought to do so by bringing together scholars with

technical expertise in theory development, critical analysis and curriculum

development, KPMG professionals with real-world experience applying

measurement and attestation models in complex real-life decision-making

venues, and business managers with a wealth of practical knowledge about

their industries, business models and business processes. I believe that after

presented in this volume were used in the classes.

Experiencing the

unfolding of the discovery process in the classroom by bright young minds

was both stimulating and gratifying. Students progressed rapidly from

novice-sponges who take in and react instantaneously to every new bit of

information to critical thinkers with basic systems-thinking skills for

internalizing and integrating relevant information about complex

businesses. Students came away from the learning experiences enabled by

the cases with an enhanced appreciation for the intellectual challenges of

auditing knowledge work and a sense of excitement about spending their

careers in a stimulating business-learning environment that continuously

presents novel learning opportunities. Now more than ever we collectively

B U S I N E S S

need to work hard to show students that our profession is intellectually

R E S E A R C H

sections of the introductory assurance course at UIUC. Several of the cases

A N D

During the 2001/2002 academic year, I co-taught with faculty several

D E V E L O P M E N T

firsthand the positive impact of the materials produced by our program.

C A S E

at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC), I have had the good fortune to observe

M E A S U R E M E N T

In my capacity as a Visiting Executive Lecturer at the University of Illinois

P R O G R A M

reading this volume, you will agree that we have achieved our goal.

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

C A S E S

I N

S T R AT E G I C - SYS T E M S

A U D I T I N G

IX

F O R E W O R D

challenging and rewarding, and the cases in this volume will help educators

to build that awareness through actual classroom experiences.

I hope that readers of this volume will give serious consideration to

adopting some of the cases developed under our program. Using these

cases will create in you a great sense of satisfaction that your students are

better equipped to critically analyze a business and apply this essential

knowledge to perform a better audit.

On behalf of all of my partners at KPMG, I would like to thank all of the

case developers for a job well done. We look forward to continuing our

P R O G R A M

National Managing Partner,

Assurance & Advisory Services Center, KPMG LLP

Visiting Executive Lecturer, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

July 23, 2002

B U S I N E S S

M E A S U R E M E N T

C A S E

D E V E L O P M E N T

A N D

D. Scott Showalter

R E S E A R C H

collaborations with you to improve audit education and practice.

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

X

K P M G

A N D

U N I V E R S I T Y

O F

I L L I N O I S

AT

U R B A N A - C H A M PA I G N

P R E FA C E

In the fall of 1997, KPMG Peat Marwick LLP1 (KPMG), the University of

Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC), and the KPMG Foundation

(Foundation) introduced the Business Measurement Case Development &

Research Program (Program) to the academic community. At that time,

many accounting educators were expressing concerns about their ability to

keep classroom materials and research activities current, given the rapid

pace at which commerce, business measurement, and auditing were

changing. Responding to this emerging need, KPMG, UIUC, and the

Foundation established the Program to support development of educational

materials grounded in current audit concepts and methods and set in realworld business contexts, and to offer successful case developers

presents a conceptual overview of, and blueprint for, strategic-systems

auditing (SSA)—an evolving business knowledge-acquisition approach

that guides the focus, breadth, and depth of the auditor’s knowledge

acquisition in today’s complex business environment. Under the SSA

approach, an auditor seeks to obtain an understanding of the client’s

business model—a simplified repesentation of the network of causes and

effects that determine the extent to which the entity creates value and earns

profits.

Some of the more important business-model causal factors

assessed by an auditor employing SSA are: (1) environmental factors that

B U S I N E S S

present opportunities to the entity for creation of strategic advantages; (2)

R E S E A R C H

1997 to all academic members of the American Accounting Association,

A N D

from UIUC and KPMG. The monograph, which was distributed gratis in

D E V E L O P M E N T

KPMG Business Measurement Process (Bell et al. 1997) by representatives

C A S E

monograph Auditing Organizations Through a Strategic-Systems Lens: The

M E A S U R E M E N T

The initial step in creating the Program was joint authoring of the

P R O G R A M

opportunities for innovative research.

1 Now KPMG LLP.

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

C A S E S

I N

S T R AT E G I C - SYS T E M S

A U D I T I N G

XI

P R E FA C E

other external forces and trends presenting risks that can threaten the

entity’s ability to create and sustain these strategic advantages; (3) key

business processes and underlying competencies that are critical to

successful execution of the entity’s strategy; (4) business process risks

threatening the entity’s ability to create and sustain process advantages, and

related business controls; and (5) residual strategic and process risks and

their implications for financial reporting and audit risks. KPMG’s Business

Measurement Process (BMP) is presented in the monograph as a working

example of the SSA framework.

After the monograph was disseminated in 1997, KPMG and UIUC issued a

under the Program. The RFP delineated two interrelated Program phases:

(1) development of a case based on a major company for classroom use as

a vehicle for students to enhance their understanding of SSA concepts and

methods and (2) follow-on scholarly research to advance SSA knowledge

and methods. Under the Program guidelines, case development was funded

up to a maximum of $40,000 per case with follow-on research opportunities

for funding up to a maximum of $50,000 per research study. Twenty-three

case proposals totaling $814,546 were selected for funding during the

Program’s three annual submission periods. The eight cases that were

awarded funding in 1998 during the Program’s first submission period are

presented in this volume.

M E A S U R E M E N T

We begin this volume with a chapter that introduces SSA concepts and

extends the ideas presented in the original Bell et al. monograph. Ideas

B U S I N E S S

C A S E

D E V E L O P M E N T

A N D

R E S E A R C H

P R O G R A M

Request For Proposals (RFP) inviting scholars to compete for funding

chapter describes how the cases contained in this volume address key

XII

K P M G

discussed in Chapter 1 include elaborations on systems thinking, the

connection between client business risk and audit risk, and the formation

and utility of mental models in strategic-systems auditing. Thereafter, the

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

A N D

U N I V E R S I T Y

O F

I L L I N O I S

AT

U R B A N A - C H A M PA I G N

P R E FA C E

antecedents and knowledge-acquisition activities essential to SSA. The

chapter concludes by providing suggested responses to eight questions that

are (or perhaps should be) frequently asked about SSA. The second chapter

is intended to help instructors identify an efficient and synergistic subset of

the eight cases to assign in business courses. For a quick overview of the

topics covered in the cases, we provide tables characterizing each case in

terms of industry membership, strategic analysis frameworks, and business

processes, and the attendant business risks, critical success factors, and key

performance indicators. We also discuss in this chapter the rich information

set contained in the teaching notes that accompany each of the cases.

900,000 hits. More than 100,000 copies of the monograph were requested by,

and distributed to, professors and business and accounting professionals, and

more than 31,000 copies of completed cases were downloaded.2

The

remaining in–process cases funded under the Program will be posted to the

Web site when they are completed.

We would like to thank KPMG, the KPMG Foundation, and UIUC for

providing financial and other resources to make the Program possible. We

gratefully acknowledge the following people for their significant support of

and contributions to the Program: Frank Marrs (CEO, Gupton Marrs

2 These download numbers likely understate the case usage rate because some professors reproduce

multiple copies from one downloaded case copy.

R E S E A R C H

ended December 31, 2001, the Program’s Web site received approximately

A N D

valuable aids for successful use of the Program’s cases. During the two years

D E V E L O P M E N T

Professors who have used these teaching notes tell us that they are extremely

C A S E

for all cases funded under the Program free-of-charge at the Web site.

M E A S U R E M E N T

edu/kpmg-uiuc. Also, professors can obtain comprehensive teaching notes

B U S I N E S S

for download free-of-charge at the Program’s Web site: http://www.cba.uiuc.

P R O G R A M

The monograph and all cases funded under the Program are available

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

C A S E S

I N

S T R AT E G I C - SYS T E M S

A U D I T I N G

XIII

P R E FA C E

International and formerly at KPMG); Terry Strange, Scott Showalter,

Marty Finegan, Bernie Milano, Michael Tolpa, Ram Menon, Pam Bullis,

and Karen Bell (KPMG and the KPMG Foundation); Jeff Arricale (T. Rowe

Price and formerly at KPMG); Mark Peecher, Clif Brown, and Jean Seibold

(UIUC); Howard Thomas (Dean, Warwick Business School, University of

Warwick and formerly at UIUC); Robert Knechel (University of Florida);

and members of the Program Advisory Board—Katherine Schipper, (FASB

and formerly at Duke University), Krishna Palepu (Harvard University),

and William Kinney (University of Texas at Austin). In addition, we thank

all of the case developers, KPMG partners and staff, and client management

who gave so unselfishly of their time and other resources to nurture each of

Timothy B. Bell/KPMG LLP

Ira Solomon/UIUC

B U S I N E S S

M E A S U R E M E N T

C A S E

D E V E L O P M E N T

A N D

R E S E A R C H

P R O G R A M

the case projects funded under the Program.

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

XIV

K P M G

A N D

U N I V E R S I T Y

O F

I L L I N O I S

AT

U R B A N A - C H A M PA I G N

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

P R O G R A M

Timothy B. Bell

KPMG LLP

Mark E. Peecher

B U S I N E S S

M E A S U R E M E N T

C A S E

D E V E L O P M E N T

A N D

R E S E A R C H

Ira Solomon

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

C A S E S

I N

S T R AT E G I C - SYS T E M S

A U D I T I N G

1

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

B

y the end of the 20th century,

advances in information technologies had reduced substantially the

propensity for error in processing routine business transactions.1 These

same forces, however, had dramatically altered the nature and complexity of

business activities and relationships. Concurrently, accelerating innovation

and competition, proliferation of stock-based compensation, and

heightened stock market sensitivity to unexpected earnings had increased

application of audit sampling to populations of routine transactions and

account balance details processed by error-prone manual accounting

systems. These methodologies, however, became increasingly less efficient

and effective as innovations in information technology altered the business

landscape. New methodologies were needed to help auditors obtain the indepth business knowledge required to assess the economic implications of

complex business relationships and activities and to guide the search for

instances in which managers may have exploited ambiguous and complex

1 Several studies have provided evidence of low error rates in the recording of routine business

transactions, especially those processed electronically, and a higher propensity for misstatement in

nonroutine transactions, especially those recorded manually by management. See, for example,

Houghton, C. W., and J. A. Fogarty, “Inherent Risk,” Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory (Spring

1991), pp. 1-21; Bell, T. B., W. R. Knechel, J. L. Payne, and J. J. Willingham, “An Empirical

Investigation of the Relationship Between the Computerization of Accounting Systems and the

Incidence and Size of Audit Differences,” Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory (Spring 1998, pp.

13-38); and Bell, T. B, and W. R. Knechel, “Empirical Analyses of Errors Discovered in Audits of

Property and Casualty Insurers,” Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory (Spring 1994), pp. 84-100.

R E S E A R C H

A N D

Audit methodologies traditionally had heavily emphasized broad-based

D E V E L O P M E N T

to material fraudulent financial reporting.

C A S E

auditor’s responsibility for planning and performing the audit with respect

M E A S U R E M E N T

in, among other things, an expansion and concomitant clarification of the

B U S I N E S S

complex, rules-based financial accounting standards. These forces ushered

P R O G R A M

the temptation for managers to exploit ambiguities in a growing body of

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

C A S E S

I N

S T R AT E G I C - SYS T E M S

A U D I T I N G

3

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

accounting rules. In light of these trends, several of the larger public

accounting firms adapted their audit approaches to more heavily emphasize

the need to develop a sufficiently deep understanding of the past, present,

and future states of auditees’ businesses. Bell et al. (1997) call these new

audit approaches strategic-systems auditing (SSA), and present an overview

of KPMG’s Business Measurement Process (BMP) as an example of a SSA

approach.

An important aspect of SSA is an emphasis on obtaining the in-depth

knowledge needed to develop rich mental models (defined later) of the

business. Such business-knowledge-laden mental models are essential for

P R O G R A M

the auditor to discern the real states of the business, assess business risks,

and appraise attendant controls. Provided that the auditor’s mental model

contains sufficiently faithful representations of relevant past, current and

R E S E A R C H

future states of the business, he/she should be able to (1) make effective pretesting assessments of the risk of material misstatement (RMM) in

managers’ assertions, (2) design follow-on tests of controls and financial

A N D

statement amounts and disclosures that are sufficiently reliable and apply

them effectively, (3) make correct interpretations of the results of such tests,

D E V E L O P M E N T

and (4) form final assessments of RMM based on the accumulated results

of auditing procedures that provide sufficient risk assessment (i.e.,

estimation) power.

C A S E

Importantly, auditors employing SSA use in-depth knowledge of the

M E A S U R E M E N T

business to assess risk factors related to fraudulent financial reporting. In

particular, the degree to which managers have incentives to intentionally

misstate the financial statements depends largely on the real current

profitability of the business, its prospects for future profitability, and

B U S I N E S S

managers’ beliefs about the impact on their personal wealth of market

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

4

K P M G

A N D

U N I V E R S I T Y

O F

I L L I N O I S

AT

U R B A N A - C H A M PA I G N

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

participants’ or others’ perceptions of these states.2 If poorly controlled,3

even currently profitable businesses can develop significant problems that

managers may seek to disguise through inappropriate accounting and

disclosure. Therefore, the risk that the auditor will fail to detect fraudulent

financial reporting should decrease substantially when an auditor develops

a veridical mental model of the business that reveals the business is wellcontrolled.

To gain an appreciation for the difficulty of detecting fraudulent financial

reporting, consider how the audit team’s knowledge acquisition task differs

from that of a physician. Patients describe their symptoms to physicians in

perpetrating auditees distort symptoms in the first place and may conceal

symptoms from auditors as they inquire and conduct other tests. The

primary difference between these two diagnostic inference venues,

therefore, is that, unlike physicians, auditors face a much more difficult

C A S E

M E A S U R E M E N T

B U S I N E S S

2 Paragraph No. 7 of the exposure draft entitled, Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit

(AICPA Auditing Standards Board, February 28, 2002) discusses the importance of obtaining an

understanding of incentives that may motivate managers to commit fraud. Paragraph No. 7 states the

following. “Three conditions generally are present when fraud occurs. First, management or other

employees have an incentive or are under pressure, which provides a reason to commit fraud. Second,

circumstances exist—for example, the absence of controls, ineffective controls, or the ability of

management to override controls—that provide an opportunity for a fraud to be perpetrated. Third,

those involved are able to rationalize a fraudulent act as being consistent with their personal code of

ethics. Some individuals possess an attitude, character, or set of ethical values that allow them to

knowingly and intentionally commit a dishonest act. However, even otherwise honest individuals can

commit fraud in an environment that imposes sufficient pressure on them. The greater the incentive

or pressure, the more likely an individual will be able to rationalize the acceptability of committing

fraud. Identifying individuals with the requisite attitude to commit fraud, or recognizing the

likelihood that management or other employees will rationalize to justify committing the act, is

difficult.”

3 The concept of business control as used here extends well beyond the concept of internal accounting

control. For example, a business whose strategy is no longer viable is not well controlled, or a

business that executes its core business processes so poorly that time, cost, and quality are negatively

impacted so as to lessen its competitiveness is not well controlled.

D E V E L O P M E N T

A N D

problem-detection task. Auditors must acquire knowledge of symptoms

R E S E A R C H

to diagnose the probable cause(s) of the symptoms. In contrast, fraud-

P R O G R A M

the first place, and physicians follow up with a series of inquiries and tests

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

C A S E S

I N

S T R AT E G I C - SYS T E M S

A U D I T I N G

5

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

(e.g., potential business problems), and diagnose their causes, via an

intensive and difficult search within strategically altered information

environments.4

Among other things, the SSA knowledge acquisition methodology directly

guides the auditors’ search for symptoms of the existence and emergence of

significant business problems.

The methodology guides the auditor’s

acquisition of information required to construct a mental model of the

organization using the systems-thinking approach while emphasizing

identification and assessment of auditee business risks. This approach

focuses the auditor’s knowledge acquisition activities on the significant

P R O G R A M

interdependencies among subsystems within the broad business system

comprising the auditee organization, other influential organizations and

agents, and other forces within the auditee’s economic environment. The

R E S E A R C H

SSA business risk assessment orientation defines one important audit

D E V E L O P M E N T

A N D

knowledge acquisition objective in terms of the need to identify and learn

B U S I N E S S

M E A S U R E M E N T

C A S E

4 Appendix A of the exposure draft entitled, Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit

[AICPA Auditing Standards Board, February 28, 2002] presents examples of business problems that

can create incentives to commit fraud. The four broad categories of examples presented for the

Incentives/Pressures condition in the appendix are: a) financial stability or profitability is threatened by

economic, industry, or entity operating conditions; b) excessive pressure exists for management to meet

the requirements or expectations of third parties (e.g., investment analysts); c) management or the

board of directors’ personal net worth is threatened by the entity's financial performance; and d) there

is excessive pressure on management or operating personnel to meet financial targets set up by the

board of directors or management. The types of incentives and pressures indicated in categories b)

through d) are determined largely by the existence of business problems such as those indicated in

category a). Also, whether the opportunities and attitude/rationalizations conditions would be relevant

to the risk of fraud depends largely on whether such business problems exist. Therefore, it would

appear that the auditor's assessment of the risk of fraud should focus largely on the detection of

business problems that could lead ultimately to financial instability and profit erosion.

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

6

K P M G

A N D

U N I V E R S I T Y

O F

I L L I N O I S

AT

U R B A N A - C H A M PA I G N

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

the nature of symptoms of significant business problems within the auditee

organization’s network of activities and interrelationships. 5

Auditors who acquire a strategic-systems understanding of the auditee

organization will have obtained a deep understanding of the important

states of the world that shape the fundamental economic status and

trajectory of the organization. This knowledge lays a strong foundation for

all remaining knowledge acquisition activities that culminate collectively in

the auditor’s opinion on the veracity of the financial statements.

This chapter is intended to clarify and extend thinking in the Bell et al.

organizations and then comment on some key properties of auditors’ mental

models.

Finally, we discuss how systems-thinking skills will enhance

students’ ability to build their own mental models of business organizations

5 Risk often is viewed as the possibility of future harm that could be caused by the occurrence of an

uncertain future event(s). However, an auditor using the SSA methodology to assist with his/her

problem detection is searching for symptoms of existing business problems that have already caused

harm to the business, but which may be unknown to the auditor, as well as possibilities of uncertain

future events that could cause harm to the business. Knowledge of existing business problems should

be helpful to the auditor’s assessment of the risk of fraud, and to developing expectations for financial

statement amounts and disclosures. Knowledge of possibilities of future harm to the business is needed

to assess the reasonableness of accounting estimates, as well as to reduce search costs during problem

detection on future audits. When we say that SSA “emphasizes identification and assessment of auditee

business risks,” included therein are existing business problems that have already caused harm to the

business, but are unknown to the auditor, and possible future events that could cause harm to the

business. The SSA business risk orientation speaks to the auditor’s need to search for past, current, and

future events or forces that have already, or can possibly in the future, cause harm to the business.

6 The Bell et al. (1997) monograph is available in PDF and html formats at

http://www.cba.uiuc.edu/kpmg-uiuc/monograph.html.

R E S E A R C H

systems auditors employ to develop rich mental models of auditee

A N D

describe four interrelated knowledge-acquisition activities that strategic-

D E V E L O P M E N T

between auditee organizations’ business risks and the RMM. We next

C A S E

SSA. The remainder of this chapter begins by discussing the strong relation

M E A S U R E M E N T

to help the reader understand the fundamental antecedents and rationale of

B U S I N E S S

Lens: The KPMG Business Measurement Process.6 Our overarching goal is

P R O G R A M

(1997) monograph, Auditing Organizations Through a Strategic-Systems

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

C A S E S

I N

S T R AT E G I C - SYS T E M S

A U D I T I N G

7

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

and, based on feedback received from instructors and students, we provide

responses to frequently asked questions on key SSA principles.

An Overview of SSA

Unfortunately, in a great many places in our society, including academia and most

bureaucracies, prestige accrues principally to those who carefully study some aspect

of a problem, while discussion of the big picture is relegated to cocktail parties. . . . .

Now the chief of an organization, say a head of government or a CEO, has to behave

as if he or she is taking into account all the aspects of a situation, including the

interactions among them, which are often strong. It is not so easy, however, for the

chief to take a crude look at the whole if everyone else in the organization is concerned

only with a partial view.

P R O G R A M

M. Gell-Mann7

Perhaps the most important principle giving rise to the need for SSA is the

strong relation between RMM and the auditee’s business risks.

R E S E A R C H

Consequently, strategic-systems auditors believe that reliable assessments

of economic systems within which auditee organizations operate together

with auditee organizations’ business risks are needed to form audit opinions

A N D

on financial statements. Auditees’ business risks can change rapidly and

D E V E L O P M E N T

looking exclusively within the audited organizations. SSA has arisen,

C A S E

these changes frequently occur for reasons that cannot be discerned by

important web of interconnects between the auditee and other

therefore, in part because it addresses an endogenous demand for a

conceptual framework that helps one to meaningfully and simultaneously

assess an auditee’s business risks and RMM in light of an increasingly

M E A S U R E M E N T

organizations.

Some persons have trouble envisioning how business risks—threats to the

organization’s attainment of its strategic objectives—relate to RMM. The

B U S I N E S S

link can be clarified by a valuation assertion example. Consider an auditee

7 Gell-Mann, M., “The simple and the complex,” in Complexity, global politics, and national security, D.

S. Alberts and T.J. Czerwinski (eds.) Washington, D.C.: National Defense University (1996).

http://www.ndu.edu/inss/books/complexity/index.html (May 30, 2001).

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

8

K P M G

A N D

U N I V E R S I T Y

O F

I L L I N O I S

AT

U R B A N A - C H A M PA I G N

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

organization whose strategic objectives crucially depend on maintaining

harmonious relations with an alliance partner responsible for distributing its

products. The SSA auditor would monitor indicators of the relations with

the alliance partner because, if a dispute were to break out, numerous

business risks would elevate. Given such a dispute, an auditor employing

SSA might question the valuation of the accounts receivable from the

alliance partner and the appropriateness of recognizing alliance-related

revenues. Further, the RMM may become elevated more systemically with

respect to asset valuation if, going forward, previously anticipated

economic benefits related to the alliance were no longer expected. Such

questions can be raised, for example, using the IDEC case that appears in

incurring additional financing costs). Importantly, IDEC reduces such risks

through contracting and other alliance relationship management activities.

Another key SSA principle is anticipating how other entities’ actions and

business risks generate ripple effects that can affect auditee organizations’

business risks and, hence, RMM. The Lincoln Savings and Loan (LSL)

case, for example, illustrates how a complex interaction between interest

rate changes, regulators’ policy decisions, aggressive auditee management,

and real estate conditions can create derivative effects that significantly

increase RMM. The LSL case presents an organization that may not be able

to remain viable by investing more resources towards its historic practice of

B U S I N E S S

managing the interest rate spread. The interest rates required to recruit and

R E S E A R C H

business risks at IDEC (e.g., the inability to meet obligations without

A N D

with the alliance partner Genentech could itself heighten a number of other

D E V E L O P M E N T

significant source of IDEC’s operating cash flow and revenue, a dispute

C A S E

breakthrough drug that IDEC’s scientists discovered. Because the drug is a

M E A S U R E M E N T

Genentech, an organization that is responsible for distributing a

P R O G R A M

this volume. IDEC receives milestone payments from alliance partner

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

C A S E S

I N

S T R AT E G I C - SYS T E M S

A U D I T I N G

9

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

retain customer deposits nearly exceeds the interest rates earned on longerterm home mortgages. Because it is a savings and loan organization, LSL

is limited by regulations as to the types of loans that it can make. As profits

erode, aggressive auditee management begins to invest in high risk

securities and real estate. But the real estate market turns down and,

regrettably, the aggressive auditee management engages in fraud. Whereas

using a traditional audit approach the LSL auditor did not detect this fraud,

the strategic-systems auditor may well have fared better by considering

technical compliance with GAAP against the backdrop of the

aforementioned business developments and interactions.

financial statement business measures reconcile with the auditors’

knowledge-laden expectations. These expectations concern both financial

statement and nonfinancial statement business measures and the

interrelationships among them. The strategic-systems auditor acquires

knowledge about the auditee’s strategy for creating value, its competitive

position, and its key business processes. Such knowledge helps the auditor

to identify and assess the auditee’s current business problems and business

risks.

Generally, to the extent that the auditee’s business risks are

uncontrolled and/or significant past or current business problems exist,

RMM increases, so it is critical for the auditor to develop an awareness of

these important states of the business.

Four interrelated knowledge acquisition activities within SSA are strategic

analysis (SA), process analysis (PA), business risk assessment (RA), and

business measurement (BM). SA and PA are conducted in sequence, with

the former informing the auditor about which business processes are critical

to attainment of the auditee’s strategic objectives.

RA and BM are

B U S I N E S S

M E A S U R E M E N T

C A S E

D E V E L O P M E N T

A N D

R E S E A R C H

P R O G R A M

Using SSA, auditors focus on the extent to which an organization’s

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

10

K P M G

A N D

U N I V E R S I T Y

O F

I L L I N O I S

AT

U R B A N A - C H A M PA I G N

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

conducted continuously and recursively throughout the audit.

Becoming

knowledgeable about the auditee’s business risks and business measures

helps auditors to contemplate RMMs about which one naturally should be

concerned and to discover other RMMs that should make them concerned.

Just as N. Rothschild once said, “There is no point getting into a panic about

the risks of life until you have compared the risks which worry you with

those that don’t but perhaps should.”8

During SA, the auditor acquires knowledge of the organization’s strategic

position, the markets in which it competes, its products and services, the set

of external forces and agents that should influence the auditee’s behavior,

situated and likely to be headed within its economic landscape, the auditor

can develop rudimentary financial statement expectations and identify the

business processes critical to the auditee’s attainment of strategic objectives.

Additionally, such an understanding helps the auditor to formulate

organization. PA equips the auditor with a deep understanding of core

business processes’ inputs, activities, outputs, critical success factors

(CSFs), and key performance indicators (KPIs). A CSF is a business

activity (or set of activities) that must be performed exceptionally well for

the organization to attain its strategic objectives. At the entity level core

business processes are CSFs because of their importance to the attainment

of strategic objectives. Within business processes, a subset of critical

8 See Rothschild, N., “Coming to grips with risk.” Address on BBC television reprinted in the Wall

Street Journal (March 13, 1979).

C A S E

those that create value for, and/or sustain the value-creation potential of, the

M E A S U R E M E N T

identifies and analyzes its core business processes. Core processes are

B U S I N E S S

Given the organization’s strategic position and objectives, the auditor

D E V E L O P M E N T

A N D

rudimentary business risk and RMM assessments.

R E S E A R C H

among other behaviors. By coming to understand where the auditee is

P R O G R A M

and the nature of the auditee’s suppliers, customers, and alliance partners,

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

C A S E S

I N

S T R AT E G I C - SYS T E M S

A U D I T I N G

11

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

activities largely will determine the level of achieved process performance.

These activities, individually and in the aggregate, are CSFs at the process

level. A CSF at the process level can be, for example, the presence of

effective controls over a key activity within a business process. KPIs

include both backward- and forward-looking performance measures that

provide significant diagnosticity or predictive value, respectively, with

respect to the past, current, or likely future states of at least one CSF. KPIs

can be financial or nonfinancial and they typically are quantitative. Highlevel divisional managers use KPIs at the division level both to establish

accountability and decide on rewards for intra-division middle managers

and to identify how division operations can be improved in the future.

Also within PA, the auditor seeks to obtain an understanding of the linkages

between process-level performance and routine and nonroutine business

transactions, accounting estimates, financial statement account balances,

and other financial statement disclosures. A final yet critical task within PA

is to reflect on residual business risks to help design and execute other audit

procedures that either corroborate or refute the reliability of the

organization’s asserted KPIs.

If auditors determine that an organization’s KPIs are relevant and reliable

business measures, they can proceed with audit risk analyses. If, however,

the auditor determines that an organization’s KPIs are of questionable

M E A S U R E M E N T

reliability, it may be infeasible to audit the organization’s financial

statements in a cost-effective manner. In theory, there may be instances in

B U S I N E S S

C A S E

D E V E L O P M E N T

A N D

R E S E A R C H

P R O G R A M

Middle managers do the same within the business process subsystem.

some such instances, it may be possible to complete a bottom-up,

which an organization exercises effective control over its production of

financial statement performance measures but does not exercise effective

control over its production of business-process performance measures. In

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

12

K P M G

A N D

U N I V E R S I T Y

O F

I L L I N O I S

AT

U R B A N A - C H A M PA I G N

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

transactions-focused audit to obtain sufficient, competent evidential matter

to attain reasonable assurance. In other instances, though, scope limitations

are likely to arise because of the auditor’s inability to place the financial

statements into a meaningful strategic/business context. If such scope

limitations were material, the organization’s financial statements might not

be auditable.

Both during and after SA and PA, auditors perform RA and BM by

integrating their performance-level knowledge into their ever-evolving

mental models of the organization. When components, magnitudes, and

relationships within and among business measures that appear in the

relationships would be carefully scrutinized. This scrutiny can result in

management agreeing to adjust the financial statement items or in auditors

becoming satisfied that their expectations failed to account for legitimate

causes of the anomalies (i.e., the auditor revises his/her expectations based

on new information). In either of these cases, the auditor would issue an

unqualified audit report. An unlikely but possible outcome is that the

anomalies simply remain unresolved after scrutiny, in which case the

B U S I N E S S

M E A S U R E M E N T

C A S E

auditor may have to render a modified or disclaimer audit opinion.

R E S E A R C H

assessments of RMM would be elevated and, as such, the items or

A N D

If, however, such items or relationships fail to conform to expectations,

D E V E L O P M E N T

derived expectations, auditors may be persuaded that the RMM is fairly low.

P R O G R A M

organization’s financial statements harmonize with auditors’ analytically

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

C A S E S

I N

S T R AT E G I C - SYS T E M S

A U D I T I N G

13

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

SSA and the Auditor’s Mental Model

Mental models consist of organized knowledge, integrated data about

patterns of cues, and rules for linking knowledge and cues (e.g., presumed

causal and/or associative relationships). Mental models are abstractions of

reality and their usefulness does not necessitate a complete, one-to-one (i.e.,

an isomorphic) representation of all facets of an auditee organization.

Typically, even for complex systems, a many-to-one abstraction from the

real world to elements of a mental model (i.e., a homomorphic

representation) will suffice for decision-making purposes.9

organization prior to the start of the current year’s audit engagement. If the

engagement is a continuing one, the auditor’s mental model will be based

on knowledge obtained during prior engagements and updated by industry

information. If, conversely, the engagement is new, the proposal process is

likely to have served as the primary impetus for formulating at least a

During the current year’s engagement, the auditor employing SSA draws on

humans simultaneously can manipulate only five to seven chunks of

B U S I N E S S

M E A S U R E M E N T

D E V E L O P M E N T

rudimentary mental model of the auditee organization.

C A S E

A N D

R E S E A R C H

P R O G R A M

Auditors likely possess at least a rudimentary mental model of the auditee

a variety of tools, some developed by experts in strategic management or

business policy, to reduce the cognitive load required to build a reliable

mental model of the organization.10 A robust finding in psychology is that

information at a time in working memory. Given the complexity of auditee

organizations’ economic webs, auditors benefit when environmental and

organizational factors can be chunked by virtue of shared relations to the

auditee organization (e.g., alliance partners).

9 Holland, J. H.. K. J. Holyoak, R.E. Nisbett, and P.R. Thagard, Induction: Processes of inference,

learning, and discovery (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1986).

10 See Chapter 2 for more discussion on specific tools that may be useful during SA.

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

14

K P M G

A N D

U N I V E R S I T Y

O F

I L L I N O I S

AT

U R B A N A - C H A M PA I G N

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

One way in which the auditor uses his or her mental model is to simulate

outcomes that are likely to occur (or have already occurred but are

unknown) within the auditee organization’s economic web. Whether an

auditor’s mental model is sufficient to allow reliable simulation is,

ultimately, a matter of professional judgment. Criteria for gauging the

sufficiency of one’s mental model, however, do exist. Gary Klein, a theorist

and consultant on decision-making, provides three criteria for judging

mental model reliability: coherence, applicability, and completeness.11

Coherent models allow one to understand why actions by and interactions

between key agents and organizations make collective sense. Models that

do not explain why a key organization’s actions make sense in the context

to influence the behavior of diverse organizations.

Once auditors believe that their model is sufficiently reliable, they run their

mental models. The act of running a mental model involves cognitively

simulating probable future interactions (or past but unknown interactions)

among observed cues to develop expectations for levels and

interrelationships (in degree and direction over time) among a group of

interrelated performance measures. By assessing the degree of expected

articulation among such a group of measures (including nonfinancial

statement and financial statement measures that originate within auditee

11 Klein, G., Sources of Power: How people make decisions (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1999) p. 58.

R E S E A R C H

should be able to develop expectations about how intermediaries are likely

A N D

leaps of faith about inter-organizational behaviors. For example, auditors

D E V E L O P M E N T

statements). Complete models do not require the auditor to make large

C A S E

can be more impoverished than models for conducting audits of financial

M E A S U R E M E N T

made (i.e., models required for conducting reviews of financial statements

B U S I N E S S

one with the necessary degree of assurance for the decisions that need to be

P R O G R A M

of other organizations’ actions lack coherence. Applicable models provide

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

C A S E S

I N

S T R AT E G I C - SYS T E M S

A U D I T I N G

15

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

organizations or other organizations), auditors powerfully analyze whether

current- and future-period financial statements make sense.

Within the Wells Fargo case, for example, students identify and interpret a

set of nonfinancial performance measures related to the design and

development of B2B e-commerce services. These measures reveal current

states of Wells Fargo’s overall business and are leading indicators of likely

future financial statement performance measures. As such, these measures

have considerable utility for assessing the RMM associated with present

and future financial statement amounts and disclosures. When auditors

better assess the level and underlying sources of the RMM, they are better

assessments decrease with greater convergence between the organization’s

financial statement business measures and auditors’ SA/PA-based

expectations of the same.

A sometimes overlooked objective of SSA is to seek to ensure that entire

audit teams, not just engagement partners, acquire rich mental models of

the systems of which audited organizations are a part. Ensuring meaningful

degrees of homogeneity in the formation and refinement of audit team

members’ mental models helps improve audit effectiveness and efficiency.

Even if, as some may argue, most engagement partners historically have

cultivated rich mental models, SSA provides value by reducing

idiosyncratic variation in mental models across partners and subordinate

auditors. Reduced variation makes it easier for the team to communicate

business risks and RMMs and increases the subordinate auditors’ awareness

of important states of the business that provide the context for other

audit work.

B U S I N E S S

M E A S U R E M E N T

C A S E

D E V E L O P M E N T

A N D

R E S E A R C H

P R O G R A M

able to design additional procedures to reduce audit risk. In general, RMM

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

16

K P M G

A N D

U N I V E R S I T Y

O F

I L L I N O I S

AT

U R B A N A - C H A M PA I G N

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

Students may not appreciate all of the benefits that accompany the audit

team’s explicit formation and sharing of its mental models. When the audit

team develops a shared mental model of an audited organization,

collectively the team members become more aware of omissions and

maintained assumptions. Some assumptions, as it may turn out, may need to

be refined or discarded. Increased audit team situation awareness and scrutiny

of its shared mental model justify greater confidence when the team reasons

about how changes within or outside audited organizations’ boundaries will

affect RMM. The team can better judge whether proposed lines of audit

inquiry will be diagnostic given explicit communication of the team’s

collective understanding of the auditee. Finally, auditors who form and share

Performance of SSA tasks requires thinking skills that receive scant

coverage in today’s auditing standards or textbooks. However, there are

several ways students can begin to acquire these skills.12 We postulate that

strong strategic-systems thinking skills facilitate auditors’ achievement of

superior performance on SSA tasks. A recent study by Jacobson (2001)

describes several types of strategic-systems thinking skills.13 The primary

B U S I N E S S

12 Research on judgment and decision making commonly uses task performance to operationalize audit

expertise. Task performance is a function of ability and experience, which provides auditors with

knowledge acquisition opportunities. Such experiences can include first-hand encounters on realworld auditing tasks and second-hand encounters such as firm training and collegiate education. See,

e.g,. Libby, R. and J. Luft, “Determinants of judgment performance in accounting settings: Ability,

motivation, and environment,” Accounting, Organizations and Society (1993) 18, 425-450 and Libby,

R., “The role of knowledge and memory in audit judgment,” Judgment and Decision-Making Research

in Accounting and Auditing. Ashton, R.H. and A.H. Ashton, Eds. 176-206 (Cambridge University

Press, 1995).

13 Jacobson, M. J., “Problem solving, cognition, and complex systems: Differences between experts and

novices,” Complexity (January/February 2001) pp. 41-49.

M E A S U R E M E N T

C A S E

hypothesis examined in the Jacobson study is that key differences exist

A N D

Systems Thinking

D E V E L O P M E N T

its own organization is impoverished in certain areas and respects.

R E S E A R C H

P R O G R A M

their mental models of auditees may learn that management’s mental model of

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

C A S E S

I N

S T R AT E G I C - SYS T E M S

A U D I T I N G

17

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

between strategic-systems scientists and undergraduates in terms of the

mental models used to aid their thinking.

Jacobson (2001) describes two fundamentally different mental models, a

clockwork model and complex systems model. These models can be

differentiated along six attributes, as shown in Table 1.14

B U S I N E S S

M E A S U R E M E N T

C A S E

D E V E L O P M E N T

A N D

R E S E A R C H

P R O G R A M

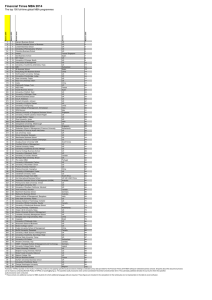

Table 1:

Different Mental Models Used to Guide Participants Thinking

Attributes

Clockwork

Mental Model

Complex Systems

Mental Model

Understanding

Reductive

Nonreductive

Control

Centralized

Decentralized

Causality

Single

Multiple

Action effects

Small actions cause

small effects

Small actions cause

large effects

Agent actions

Predictable

Stochastic

Final states

Static, teological

Equilibrative,

nonteological

Adapted from Table 1, p. 43, in Jacobson, M. J. (2001). “Problem solving, cognition, and complex

systems: Differences between experts and novices,” Complexity (January/February) pp. 41-49.

A key attribute concerns how people try to understand phenomena.

Clockwork thinkers are reductionists. They decompose systems, focus on

isolated parts (trees rather than forests), and conjecture about how these

parts influence others in a step-wise sequence. Complex-systems thinkers

focus on relations among meaningful clusters within the whole (forest).

They realize that clusters within the whole or the whole itself may differ

14 The author used eight attributes to contrast the two models. Here the attribute complexity is omitted

because only two comments were made by the participants that relate to it, and the attributes of final

causes and ontology are combined to form a final state attribute.

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

18

K P M G

A N D

U N I V E R S I T Y

O F

I L L I N O I S

AT

U R B A N A - C H A M PA I G N

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

from the sum of constituent parts and that a specific part’s influence

depends on many factors besides contiguity. As previously discussed,

auditors who adopt SSA engage in a holistic strategic analysis of auditees

to acquire a deep understanding of the economic web of which the auditee

is a part. Thus, using forest thinking, as opposed to tree-by-tree thinking, is

critical to SSA.15

Additionally, clockwork thinkers search for (usually exogenous) controls

arising from centralized agents/factors whereas complex-systems thinkers

search for (often endogenous) controls that arise from interactions among

decentralized agents/factors. To illustrate, strategic-systems auditors may

identify value-creating opportunities. Examples presented in the

Mercedes-Benz U.S. International case (MBUSI) are control structures that

interactively mitigate business risks related to events that could slow down

MBUSI’s in-sequence, just-in-time (JIT) assembly process. The auditor

to think in terms of a single cause yielding a single effect. Complexsystems thinkers envision multiple causes and effects, often with feedback

loops that make differentiating between cause and effect relatively

unproductive. In SSA, a primary reason to engage in activities such as SA

and PA is to populate the auditor’s mental model with alternative

explanations for observed phenomena so that undue reliance is not ascribed

to a single plausible explanation.

15 A discussion of forest thinking and tree-by-tree thinking appears in Barry Richmond, The “Thinking” in

Systems Thinking: Seven essential skills (Pegasus Communications, Inc., 2000).

C A S E

clockwork and complex-systems mental models. Clockwork thinkers tend

M E A S U R E M E N T

Causality is another dimension for which differences exist between

B U S I N E S S

controls reside inside and outside the MBUSI organization.

D E V E L O P M E N T

A N D

employing SSA (and the student reacting to the case) learns that such

R E S E A R C H

third-party organizations (e.g., regulators) mitigate business risks or

P R O G R A M

consider how control structures that are distributed across auditees and

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

C A S E S

I N

S T R AT E G I C - SYS T E M S

A U D I T I N G

19

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

Additionally, whereas complex-systems thinkers realize that small actions

can compound exponentially through reinforcement loops, clockwork

thinkers generally overlook leverage points associated with small actions.

Leverage point identification is an integral part of strategic-systems

auditing. In the Lincoln Savings and Loan and Wells Fargo cases, to

illustrate, a careful strategic analysis reveals how small shifts in the interestrate spread encroach on one of the historic means of generating value for

both organizations (i.e., paying less interest on deposits than is earned on

loans). Many examples of leverage points exist. A small mathematical

error that reportedly would influence the average spreadsheet user about 1

in every 27,000 years of use ballooned into a media fiasco and a $475

recent controversy over Ford Explorers and Firestone tires. Apparently, tires

with a claimed incidence of tread separation of as little as 5 per 1,000,000,

a benchmark reportedly set by Ford, may raise safety concerns.16

Finally, systems thinkers consider how random shocks could perturb the

dynamics of systems’ equilibration processes.

In contrast, clockwork

deterministic, as if they were a matter of higher-order design (teological).

as well as the control structures employed to manage these risks. This

B U S I N E S S

M E A S U R E M E N T

D E V E L O P M E N T

thinkers tend to view phenomena as being relatively static and

C A S E

A N D

R E S E A R C H

P R O G R A M

million write-off for Intel Corporation. Another example involves the

Strategic-systems auditors understand that to provide reasonable assurance

on financial statements, they must acquire a deep understanding of the

business risks that threaten the auditee’s ever-changing business processes

understanding helps the auditor anticipate how realizations of some

16 Grove, A., Only the paranoid survive: How to exploit the crisis points that challenge every company

(Bantam Books, 1999) p. 12-16). Also see, White, J. B., S. Power, and T. Aeppel, “U.S. probe of

Firestone to conclude soon; inquiry into Ford Explorer could follow,” WSJ.com (June 20, 2001)

http://interactive.wsj.com/archive/retrieve.cgi?id= SB992964124569981170.djm, June 28, 2001).

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

20

K P M G

A N D

U N I V E R S I T Y

O F

I L L I N O I S

AT

U R B A N A - C H A M PA I G N

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

business risks are likely to affect the auditee and, thus, perturb the

performance attained within its key business processes.17

Returning to the Jacobson (2001) study, seven undergraduates and nine

complex-systems scientists (some of whom were advanced graduate

students) were the participants. All participants were asked to respond to

eight questions on complex adaptive systems (e.g., How would you design

a large city to provide food, housing, goods, services, and so on, to your

citizens so that there would be minimal shortages and surpluses?). The

investigator tracked the thoughts of participants via concurrent verbal

mental models appear to be at odds in that neither group’s comments reflect

a balanced mix of clockwork and complex-systems thinking. In particular,

while more than 80 percent of the scientist group’s comments reflect a

complex-systems mental model, roughly two-thirds of the undergraduates

group’s comments reflect a clockwork mental model.

In a related study, executives and undergraduates participated in a

simulation in which they tried to maximize the quality of life for a seminomadic tribe over 25 years. To improve their chances of success,

17 For additional insight on how systems thinking provides powerful decision-making advantages see, Klein,

G., Op. Cit. (1999). Especially relevant chapters include: Ch. 4, “The Power of Intuition,” Ch. 8, “The

Power to Spot Leverage Points,” Ch. 9, “Nonlinear Aspects of Problem Solving,” Ch. 10, “The Power to

See the Invisible,” and Ch. 13, “ The Power to Read Minds.”

18 Concurrent verbal protocols are a means of collecting useful data on human's decision processes. See,

e.g., Ericsson, K. A. and H. A. Simon, Protocol analysis: Verbal reports as data (Cambridge, MA: The

R E S E A R C H

shaded rows to denote complex-systems thinking. From these data, the two

A N D

findings, using gray-shaded rows to denote clockwork thinking and bronze-

D E V E L O P M E N T

Table 2 summarizes these

C A S E

indicative of a clockwork mental model.

M E A S U R E M E N T

of a complex-systems mental model and they made fewer comments

B U S I N E S S

Overall, the scientist group of participants made more comments indicative

P R O G R A M

protocols.18

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

C A S E S

I N

S T R AT E G I C - SYS T E M S

A U D I T I N G

21

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

participants needed to recognize feedback mechanisms, interrelated

variables, and the likelihood of unpredictable side effects. The executives

performed markedly better, and their decision processes reinforced the

complex system mental model. They devoted significantly more time at the

beginning to gain a deep understanding of how variables were interrelated

and how early actions could have large effects over time. Relative to the

executives, the students acted first, stayed their course until feedback

suggested a problem, and then tried to correct their understanding. 19

Table 2:

Average Number of Comments Made Reflecting Different Mental Models

Description

Scientist Group

(n=9)

Undergraduate Group

(n=7)

0.4

3.3

Nonreductive

2.1

0.6

Centralized

0.1

2.1

Decentralized

3.6

0.7

Single

0.9

0.9

Multiple

4.9

3.1

Small actions cause small effects

0.2

1.0

Small actions cause large effects

0.4

0.0

Predictable

1.2

1.7

Stochastic

2.3

0.7

Static, teological

0.0

0.0

Equilibrative, nonteological

2.1

0.0

Understanding Reductive

Control

Causality

Action effects

Agent actions

Final states

B U S I N E S S

M E A S U R E M E N T

C A S E

D E V E L O P M E N T

A N D

R E S E A R C H

P R O G R A M

Attributes

19 Dörner, D. and J. Schölkopf, “Controlling complex systems; or, expertise as ‘grandmother’s know-how,’”

Towards a General Theory of Expertise, K. A. Ericsson and J. Smith, eds. (Cambridge University Press,

1991) pp. 218-239.

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

22

K P M G

A N D

U N I V E R S I T Y

O F

I L L I N O I S

AT

U R B A N A - C H A M PA I G N

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

Frequently Asked Questions about SSA

Following is a list of frequently asked questions about principles that are

associated with or underlie thinking skills pertinent to SSA.

Just as

students cannot master the thinking skills without actively applying and

generalizing these skills, they cannot apply and generalize such skills

without a sound understanding of their fundamental principles. Because of

the importance of the principles embedded in the following questions, we

recommend that they be assigned as homework or be used as discussion foci

within class breakout sessions.

usually occurs because students confuse their inductive learning process

with the auditor’s mental model formulation. Students need to be reminded

that when they encounter cases such as those published in this volume, they

are simultaneously learning a knowledge-acquisition skill and acquiring a

rudimentary strategic-systems model of an auditee organization. Students’

models of auditee organizations tend to be highly malleable because they

are just embarking along the learning curves associated with strategic and

business process analyses.

Auditors’ mental models, in contrast, are

unlikely to be as malleable (although research could shed light on the issue),

and even when auditors temporarily alter their mental models at an auditee’s

B U S I N E S S

suggestion, they seek corroboration. Suppose, for example, that the auditee

R E S E A R C H

whose mental models are rather well developed. Ironically, this projection

A N D

Students sometimes project the plasticity of their mental models to auditors

D E V E L O P M E N T

of the auditee organization?

C A S E

if an auditee is trying to cause the auditor to develop a false mental model

M E A S U R E M E N T

problem is that it always seems reasonable. How does an auditor ever know

P R O G R A M

1. My mental model of this organization seems reasonable to me, but the

2002 KPMG LLP, the U.S. member firm of KPMG International, a Swiss nonoperating association. All rights reserved.

C A S E S

I N

S T R AT E G I C - SYS T E M S

A U D I T I N G

23

T H E S T R AT E G I C - S Y S T E M S

A P P R O A C H T O A U D I T I N G

were to assert that, in contrast to the auditor’s current mental model, product

returns hardly ever occur. The auditor could interview large customers of

the audited organization, cross-check the assertion against quality control

business measures that are not reported in financial statements, and see if

the assertion squares with recent industry trends.

Still, students who raise this issue should be lauded for pointing out that

even auditors are well advised to guard against being overconfident in their

mental models. It is wrong to denigrate mental models because they are

sometimes wrong, but it is right to chastise auditors who become

overconfident in the mental models that they construct.20 One possible

P R O G R A M

2. When we first started talking about a new audit approach, I had

B U S I N E S S

M E A S U R E M E N T

C A S E

D E V E L O P M E N T

A N D

wrong in a significant way and to think creatively about which portions of

R E S E A R C H

remedy is for auditors, at regular intervals, to imagine that their model is

the model are most likely to be in need of refinement or corroboration.