New Ecological Paradigm

(NEP) Scale

The New Ecological Paradigm scale is a measure of

endorsement of a “pro-ecological” world view. It is

used extensively in environmental education, outdoor

recreation, and other realms where differences in

behavior or attitudes are believed to be explained

by underlying values, a world view, or a paradigm.

The scale is constructed from individual responses to

fifteen statements that measure agreement or

disagreement.

T

he New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) scale, which is

sometimes referred to as the revised NEP, is a surveybased metric devised by the US environmental sociologist Riley Dunlap and colleagues. It is designed to

measure the environmental concern of groups of people

using a survey instrument constructed of fi fteen statements. Respondents are asked to indicate the strength of

their agreement or disagreement with each statement.

Responses to these fi fteen statements are then used to

construct various statistical measures of environmental

concern. The NEP scale is considered a measure of environmental world view or paradigm (framework of

thought).

History of the NEP

The roots of the NEP are in the US environmental movement of the 1960s and 1970s, inspired by the publication

of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. Social psychologists

hypothesized that the prevailing world view of the population, called the dominant social paradigm (DSP), was

changing to ref lect greater environmental concern.

Developing valid and reliable measures of the environmental world view would help scholars better understand

the trajectory of these changes and their relationship to

demographic, economic, and behavior change in the US

population.

Among the various efforts to measure such change,

Riley Dunlap and colleagues at Washington State

University developed an instrument they called the New

Environmental Paradigm (sometimes called the original

NEP), which they published in 1978. The idea was that

this instrument could measure where a population was in

its transition from the DSP to a new, more environmentally conscious world view, a change that the NEP scale

developers thought was likely to happen. The original

NEP had twelve items (statements) that appeared to represent a single scale in the way in which populations

responded to them.

The original NEP was criticized for several shortcomings, including a lack of internal consistency among individual responses, poor correlation between the scale and

behavior, and “dated” language used in the instrument’s

statements. Dunlap and colleagues then developed the

New Ecological Paradigm Scale to respond to criticisms

of the original. Th is is sometimes referred to as the

revised NEP scale to differentiate it from the New

Environmental Paradigm scale.

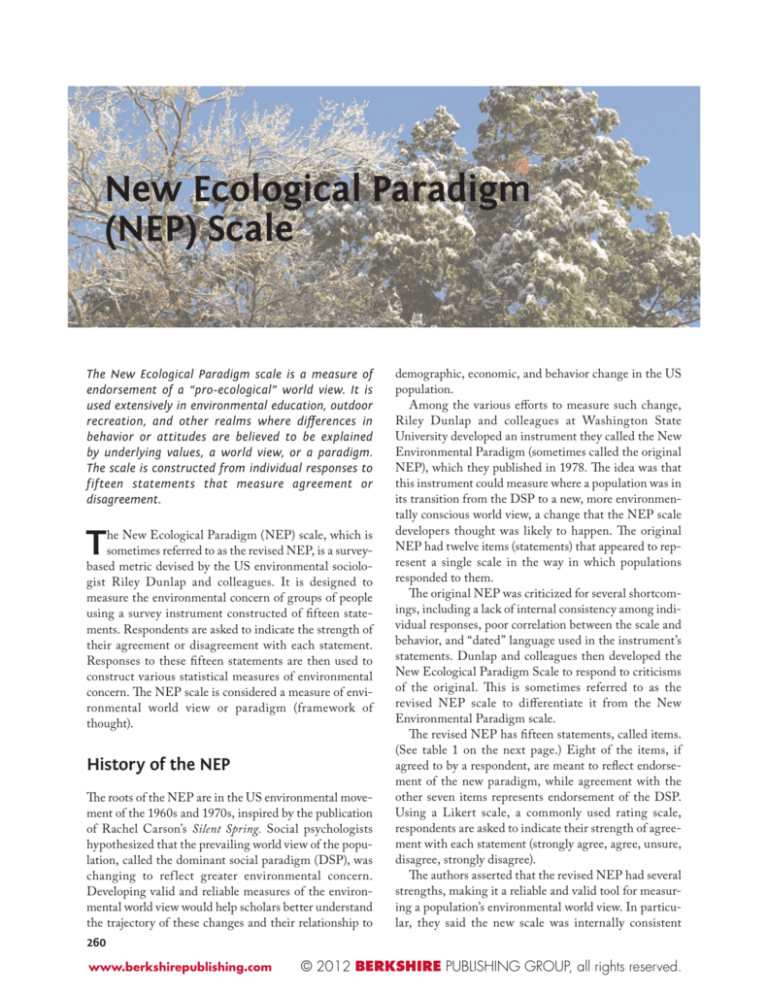

The revised NEP has fifteen statements, called items.

(See table 1 on the next page.) Eight of the items, if

agreed to by a respondent, are meant to reflect endorsement of the new paradigm, while agreement with the

other seven items represents endorsement of the DSP.

Using a Likert scale, a commonly used rating scale,

respondents are asked to indicate their strength of agreement with each statement (strongly agree, agree, unsure,

disagree, strongly disagree).

The authors asserted that the revised NEP had several

strengths, making it a reliable and valid tool for measuring a population’s environmental world view. In particular, they said the new scale was internally consistent

260

www.berkshirepublishing.com

© 2012 Berkshire Publishing Group, all rights reserved.

NEW ECOLOGICAL PARADIGM (NEP) SCALE

• 261

Table 1. Revised NEP Statements

1. We are approaching the limit of the number of people the Earth can support.

2. Humans have the right to modify the natural environment to suit their needs.

3. When humans interfere with nature it often produces disastrous consequences.

4. Human ingenuity will insure that we do not make the Earth unlivable.

5. Humans are seriously abusing the environment.

6. The Earth has plenty of natural resources if we just learn how to develop them.

7. Plants and animals have as much right as humans to exist.

8. The balance of nature is strong enough to cope with the impacts of modern industrial nations.

9. Despite our special abilities, humans are still subject to the laws of nature.

10. The so-called “ecological crisis” facing humankind has been greatly exaggerated.

11. The Earth is like a spaceship with very limited room and resources.

12. Humans were meant to rule over the rest of nature.

13. The balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset.

14. Humans will eventually learn enough about how nature works to be able to control it.

15. If things continue on their present course, we will soon experience a major ecological catastrophe.

Source: Dunlap et al. (2000).

The seven even numbered items, if agreed to by a respondent, are meant to represent statements endorsed by the dominant social paradigm

(DSP). The eight odd items, if agreed to by a respondent, are meant to reflect endorsement of the new environmental paradigm (NEP).

(people who responded to some items in one pattern

tended to respond to other items in a consistent manner)

and that it represented a measure of a single scale (that it

had unidimensionality).

Use and Critiques

The revised NEP is used widely in the United States and

in many other nations. It is used in cross-sectional assessments of the relationship of environmental world views

to attitudes on public policy, to recreation participation

patterns, and to pro-environmental behaviors. It is also

used in before-and-after studies of the effects of some

intervention or activity, such as the impact of educational

programs on environmental world views. It is probably

the most widely used measure of environmental values or

attitudes, worldwide.

The revised NEP scale has its critics. There are three

broad categories of criticism. First is the assertion that

the revised NEP scale is missing certain elements of a

pro-ecological world view and thus is incomplete.

Specifically, it is said that the scale leaves out expressions

of a biocentric or ecocentric world view that comes from

late twentieth-century environmental ethics literature.

A second line of criticism concerns the validity of the

scale. Th is comes typically from researchers who have

tried to document links between NEP scale results and

www.berkshirepublishing.com

pro-environmental behavior. When links between NEP

scale results and behavior are weak, some researchers

suggest that the scale fails to measure a world view accurately. Tests of the NEP scale as a predictor of environmental behavior are part of extensive social-psychological

research to explain the root causes of environmental

behavior.

Finally, there is considerable debate about the dimensionality of the revised NEP scale. Dunlap and colleagues argued that the NEP in both of its iterations

measures a single dimension, endorsement of a world

view that could be measured simply by adding up the

responses. Numerous studies have used a statistical technique called principal components analysis to test this.

These studies had different results, suggesting that the

NEP captured not one dimension but often three or more

dimensions. This variability in results leads some to question both the NEP’s validity (does it measure the phenomena it is claiming to measure?) and its reliability

(does it measure those phenomena in the same way across

different populations or across time?).

Future of the NEP Scale

Given its extensive use in many settings, the New

Ecological Paradigm scale will continue to be used

widely. Because no other instrument has been so

© 2012 Berkshire Publishing Group, all rights reserved.

262 • THE BERKSHIRE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SUSTAINABILITY: MEASUREMENTS, INDICATORS, AND RESEARCH METHODS FOR SUSTAINABILITY

extensively accepted as a measure of environmental world

views, it will continue to be valuable, if for no other reason than it gives researchers comparisons to make across

study types, population types, and time. The growing

body of research will create additional opportunities to

test the NEP for its reliability and validity.

More importantly, it is clear that underlying values

will have significant effects on debates around sustainability. Advocates for the usefulness of the revised NEP

scale believe that progress toward sustainability would be

reflected in shifts in NEP scale scores in the general population from endorsement of the dominant social paradigm toward endorsement of a New Ecological Paradigm.

As such, the revised NEP scale would be a fundamental

metric of progress toward sustainability. In the same

manner, public information or sustainability education

campaigns would be deemed successful if they caused a

similar shift. For the NEP scale to serve this function

effectively, however, there will need to be greater acceptance of its validity and reliability as a metric of sustainability values.

Mark W. ANDERSON

University of Maine, Orono

See also Challenges to Measuring Sustainability; Citizen

Science; Community and Stakeholder Input;

Environmental Justice Indicators; Focus Groups;

Participatory Action Research; Quantitative vs. Qualitative

Studies; Sustainability Science; Transdisciplinary Research;

Weak vs. Strong Sustainability Debate

www.berkshirepublishing.com

FURTHER READING

Dunlap, Riley E. (2008). The new environmental paradigm scale:

From marginality to worldwide use. Journal of Environmental

Education , 40 (1), 3–18.

Dunlap, Riley E.; Van Liere, Kent D.; Mertig, Angela G.; & Jones,

Robert Emmet. (2000). Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. Journal of Social Issues ,

56(3), 425–442.

Hunter, Lori M., & Rinner, Lesley. (2004). The association between

environmental perspective and knowledge and concern with species diversity. Society and Natural Resources, 17, 517–532.

Kotchen, Matthew, & Reiling, Stephen D. (2000). Environmental

attitudes, motivations, and contingent valuation of nonuse values:

A case study involving endangered species. Ecological Economics ,

31(1), 93–107.

LaLonde, Roxanne, & Jackson, Edgar L. (2002). The new environmental paradigm scale: Has it outlived its usefulness? Journal of

Environmental Education , 33(4), 28–36.

Hawcroft, Lucy J., & Milfont, Taciano L. (2010). The use (and abuse)

of the new environmental paradigm scale over the last 20 years: A

meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30, 143–158.

Lundmark, Cartina. (2007). The new ecological paradigm revisited:

Anchoring the NEP scale in environmental ethics. Environmental

Education Research, 13(3), 329–347.

Shepard, Kerry; Mann, Samuel; Smith, Nell; & Deaker, Lynley.

(2009). Benchmarking the environmental values and attitudes

of students in New Zealand’s post-compulsory education.

Environmental Education Research, 15(5), 571–587.

Stern, Paul C.; Dietz, Thomas; & Guagnano, Gregory. A. (1995).

The new ecological paradigm in social-psychological context.

Environment and Behavior, 27(6), 723–743.

Teisl, Mario, et al. (2011). Are environmental professors unbalanced?

Evidence from the field. Journal of Environmental Education , 42 (2),

67–83.

Thapa, Brijesh. (2010). The mediation effect of outdoor recreation participation on environmental attitude-behavior correspondence. The

Journal of Environmental Education , 14 (3), 133–150.

© 2012 Berkshire Publishing Group, all rights reserved.