ESTATE LITIGATION SURROGATE COURT SPECIAL CHAMBERS

advertisement

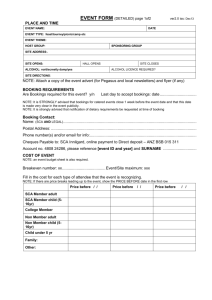

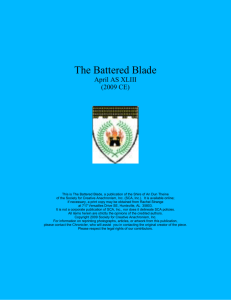

ESTATE LITIGATION ● SURROGATE COURT SPECIAL CHAMBERS APPLICATIONS PREPARED FOR ● Legal Education Society of Alberta PRESENTED ON ● February 20, 2014 – Edmonton, AB and February 24, 2014 - Calgary, AB AUTHOR ● Dragana Sanchez Glowicki Miller Thomson LLP (Edmonton) Dragana Sanchez Glowicki MILLER THOMSON LLP, 2700 Commerce Place, 10155 – 102 Street, Edmonton, AB Canada T5J 4G8 Phone: 780.429.9703, Fax: 780.424.5866, Email: dsanchezglowicki@millerthomson.com Please note: The reproduction of any part of this Paper is prohibited without the permission of the author. This article is provided as an information service only and is not meant as legal advice. Readers are cautioned not to act on the information provided without seeking specific legal advice with respect to their unique circumstances. ©Miller Thomson LLP INDEX 1. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................... 1 2. THE NUTS & BOLTS OF SPECIAL CHAMBERS APPLICATIONS ................................. 2 (A) WHAT IS THE LENGTH OF SPECIAL CHAMBERS APPLICATIONS? ................... 2 (B) HOW DO I REQUEST A HEARING DATE?.............................................................. 2 (C) HOW DO I DETERMINE WHAT IS THE BEST TIME TO SET SPECIAL CHAMBERS APPLICATIONS?................................................................................. 2 (D) WHAT ARE MY FILING TIMELINES? ...................................................................... 3 (E) WHAT PLEADINGS DO I FILE? ............................................................................... 3 (F) HOW DO I PREPARE MY PLEADINGS? ................................................................. 3 (G) WHAT IS THE FORMAT OF MY BRIEF OF LAW? .................................................. 4 (i) Introduction ...................................................................................................... 4 (ii) Facts ................................................................................................................ 4 (iii) Law................................................................................................................... 4 (iv) Argument.......................................................................................................... 5 (v) Relief Sought.................................................................................................... 5 (vi) Tabs ................................................................................................................. 5 (vii) List of Authorities.............................................................................................. 6 (H) ORAL ADVOCACY ................................................................................................... 6 3. WHEN WILL SPECIAL CHAMBERS APPLICATIONS NOT WORK? .............................. 6 4. CONCLUSION .................................................................................................................. 7 5. APPENDICES (A) ESTATE FLOW CHART (B) COURT OF QUEEN'S BENCH OF ALBERTA CIVIL PRACTICE NOTE 2 SPECIAL APPLICATIONS (C) ALBERTA SURROGATE COURT FORMS - PART 2: CONTENTIOUS MATTERS (FORMS C1, C2 and C13) 1. INTRODUCTION Estate Litigation (EL) is very different from conventional litigation. For example, there are usually many parties involved in EL. From the writer’s experience, it is standard to have 4 to 6 parties involved in an estate litigation file. Some of the parties are before the court in several capacities and have conflict of interest issues. For example, a party may have been a previous Attorney/Trustee of a dependent adult, and they are now the executor, as well as a beneficiary. Another unique aspect of EL is that the parties are usually related. When one party sues another, they are suing a family member. Other members of the family often get involved and take positions, or have supportive or conflicting stories or evidence. Since there are so many parties, the parties often change camps and for the lawyers, tracking who takes what position, who supports whose evidence, who says what, is often a nightmare. Another very unique aspect to EL is the notion of “I need to be heard”. Each member of the family wants to tell their story and have their version of events acknowledged. The “story-telling” does not often work well when trying to preserve family relations, because the story may inflame the situation. With all the psychology involved in managing an EL file, it can be complicated to resolve even a small problem. And, if all of this is not enough, EL is heard in Surrogate Court which has its own set of rules and pleadings. For all of the reasons stated above, EL needs to be broken up into pieces, and each piece handled one at a time, until all of the issues are worked through. Estate Litigators use Special Chambers Applications (SCA) to manage EL files. It is not uncommon to make multiple SCA on one estate file. SCA can be used for dealing with almost any issue. Issues of “law”1, and even issues of “fact”2 can be decided in SCA. Because of the flexibility SCA afford EL lawyers, coupled with the complex dynamics of family members, EL files rarely go to trial. 1 Alberta Rules of Court 124/2010, Rule 7.1 – allows the court to hear applications on a question of law upon facts which are either agreed to or not in dispute. 2 Supra note 1, Civil Practice Note 2, parg. 2, states that pursuant to Rule 6.611(1)(g), viva voce evidence may be adduced at a hearing in SCA. -22. THE NUTS & BOLTS OF SCA (A) What is the length of SCA? SCA are contested chambers applications which take longer than 20 minutes to argue but not longer than a half day. The types of applications which can be heard in SCA are set out in Level II of the Estate Flow Chart, attached to this paper as Appendix A3. (B) How do I request a hearing date? To request a hearing date you need to call the courthouse and ask for the special applications clerk. The clerk will allow you to tentatively reserve a date, which will then allow you time to obtain the agreement of opposing counsel and prepare your pleadings. (C) How do I determine what is the best time to set SCA? SCA are usually set a minimum of one month from the date the application is to be heard (depending on court availability), but usually 2 or 3 months ahead. The reason for this timeline is to give counsel time to prepare the necessary pleadings and meet the filing requirements. The filing timelines are set out in the Court of Queen’s Bench of Alberta, Civil Practice Note 2, Special Applications(PN2)4. PN2 is attached as Appendix B to this paper. For lack of a better way of putting it, you will want to have all your ducks in a row before you set SCA. SCA are a lot of work, but, if done at the appropriate time on a file, and if well prepared, they can be worth the effort and the result can be rewarding. You will only want to set SCA when you have collected all of your evidence, and the evidence is not in dispute. If the evidence is in dispute, you will have to ensure that you are able to dispel the evidence in dispute by using the documents filed in your pleadings. This may mean that you will need to have already exchanged Affidavits with the other side, examined on the Affidavits, and have attended to the requisite undertakings and even exchanged Affidavits of Record. Your main objective when deciding if you should make SCA is to see if it is possible to isolate 1 or 2 issues, which can be determined based on the evidence and law contained in your pleadings. You do not want to make SCA when you have evidence which will be argued and 3 The original version of Appendix A comes from the Legal Education Society of Alberta, New Surrogate Rules Binder (30.17), presented from March 8 - 24, 1995. Appendix A attached to this paper has been modified slightly from the original version. 4 supra note 1, Civ N2 – Parg. 6 (hereinafter referred to as “PN2”) -3contradicted, unless the court will have the necessary documents to make a conclusive determination of the evidence in dispute and come to a final conclusion. (D) What are my filing timelines? The filing requirements for SCA are set out in PN2, and specifically in paragraph 95. The Applicant must file their pleadings by 4:30 p.m. on the 3rd Friday before the week in which the hearing is scheduled. The Respondent’s pleadings must be filed by 4:30 p.m. on the 2nd Friday before the week in which the hearing is scheduled. Not specified in PN2, but which, in the writer’s experience, is allowed, is for the Applicant to file a second Affidavit, in response to the Respondent’s Affidavit, as soon as possible after receiving the Respondent’s filed pleadings, but no later than 4:30 p.m. on the first Friday before the week in which the hearing is scheduled. (E) What pleadings do I file? The pleadings that need to be filed are an Application (C1), Affidavit (C2)6 (see Appendix C). Brief of Law and References such as Addendums or Schedules also need to be filed. Although References are usually attached to the Brief, they may be filed in a separate document which accompanies the Brief, if the Brief is lengthy. The separate documents should be titled “Legal Brief (Book II) – Addendums and Schedules”. By the time you are ready to draft the pleadings, you have likely ran the file for several months or years. As a result, you may have numerous discovery transcripts, binders of Affidavits of Record, and undertakings. Do not lose sight of your objective. The purpose of SCA are to get the ONE or TWO issues determined. Therefore, do not get lost or bogged down with all the documents you have. Precision is your mantra when it comes to SCA! So, include only the necessary evidence to deal with the specific contested issue(s) you are targeting. (F) How do I prepare my pleadings? The quality of your pleadings is going to reflect the quality of your argument, so do not skimp on time when preparing your pleadings. The writer’s personal preference is to start by preparing the Affidavit (C2) first. Next, I then take some succinct paragraphs out of the Affidavit and copy them into the Application (C1) in order to briefly describe the facts. Third, I prepare the Order 5 6 supra note 1, Civ N2 – Parg. 9 The Interpretation Act, R.S.A. 2000, c.1-8, section 26, allows counsel artistic freedom which means that counsel does not need to be a slave to forms. The Surrogate Court forms can be revised and prepared in a way that will best aid the court with the process and resolution. -4(C13). Fourth, I paste the relief set out in the Order into the appropriate spots in the C1 (Application) and C2 (Affidavit). This system allows me to avoid duplication of efforts and ensures that the relief sought is exactly the same in all 3 pleadings and that the summary of the facts in the C1 (Application) is short and succinct. (G) What is the format of my Brief of Law? PN2 is clear, your Brief of Law should be as brief as possible7. Sometimes this is not possible, so when crafting your Brief of Law, make sure you set out definitions and decide what your abbreviations are right at the start, and then use these consistently throughout the Brief. Some suggestions for making your Brief shorter, instead of writing out numbers, simply use the numerical version, as it makes it so much easier to find dates, times, paragraphs, etc. Use abbreviations whenever possible. Your Brief should be set out in the following order: (i) Introduction • (ii) (iii) Facts • use subheadings; • tell the story in date order (if possible); • do not repeat facts; • do not embellish facts; • use your strongest facts, • use only facts that are relevant and are in evidence; • if a fact refers to a particular contested issue, say so in the Brief when you introduce the fact for the first time; and • when you are referring to a tab, transcript or exhibit, underline or bold it as it makes it very easy to locate. Law • 7 state the reason you are before the court and the relief you want. There is no place for argument in the introduction. use subheadings; supra note 1, Civ N2 – Pargs.8(a) through (c). -5- (iv) (v) (vi) • set out the rules, statutes, cases and textbook authorities you are relying on; • reference the paragraphs from the facts that substantiate or apply to the law you are quoting. You can do this simply by inserting a reference such as “(see para. 14 of the facts in support of this legal principle)”; • do not reprint lengthy quotes. Simply, bring the judge’s attention to them by referencing them in the manner set out above; • ensure all your citations are correct and correctly cited; and • always double check all your citations to ensure they actually take the justice to the accurate reference. Argument • use subheadings; • integrate the facts with the law; • write to advocate and persuade; • do not repeat, but highlight the most favourable evidence and law to allow the relief you seek to be the only conclusion that can be reached; • your argument must only deal with the issues that you have asked the court to decide. You must not argue the entire case. Be precise; • do not be boring, repetitive or disorganized, or you will lose your judge; and • do not make the mistake of arguing too much or too long. Relief Sought • restate the relief, as it is set out in your draft Order (C13), into the appropriate part of your Brief; and • include a request for costs, but state that this request is to be sought only if you are successful. Tabs • attach your statute sections, and only the relevant and important sections of the discovery transcripts; and • attach charts or tables if they can clearly and easily summarize a lot of material. -6(vii) List of Authorities • use only strong and relevant authorities; • do not use authorities that are weak or that make such small points that the authorities need further authorities to actually make any sense or to make a point; • include statutes, regulations and cases that support your arguments and the relief you seek; and • always highlight the cited portions of the law in all copies of the Brief. For more insight on preparing a good Brief, reference the Legal Education Society of Alberta, Advanced Legal Research, November 29/December 3, 2009, presented by Barbara E. Cotton, and written by Virginia May, Q.C. (H) Oral Advocacy Best practices relating to oral advocacy in SCA are the same best practices relating to oral advocacy in any court proceeding. The best way to learn oral advocacy skills is to watch good oral advocates, read well written material on the subject, and then get into the trenches and be a self-taught success! Some of the resources which can help you are: (a) The Honourable Judge Allan A. Fradsham, Alberta Practice Guide Civil Litigation Chambers Advocacy, Carswell (1997); (b) Robert F. Reid & Richard E. Holland, Advocacy: Views from the Bench (Aurora: Canada Law Book Inc., 1984); and (c) John Sopinka & Mark A. Gelowitz, The Conduct of an Appeal (Markham: Butterworths Canada Ltd., 1993). Remember, to practice advocacy is to practice the art of persuasion. Make your argument interesting, exciting and persuasive. 3. WHEN WILL SCA NOT WORK? There are times when SCA simply will not give you the desired forum to hear an issue. Such situations are when: (a) there is conflicting evidence and the evidence cannot be determined from the pleadings and/or documents filed with the court; -7(b) there is conflicting evidence and an application to have viva voce evidence entered during the SCA is denied; (c) when the court orders a trial; and (d) when the other side will not agree to have issues heard by way of SCA. Of course there may be other situations as well when SCA may not be appropriate, and these situations will depend on the facts of the particular case. 4. CONCLUSION SCA are not to be taken lightly as they are a lot of work, if done properly. However, they are an incredible tool estate litigators can use to resolve estate issues. SCA can certainly be costly, but when compared to a lengthy trial, with numerous parties, SCA can be a timely and cost effective way for legal counsel to work through various issues, and afford a family the opportunity to preserve the estate and family relations. APPENDIX A ESTATE FLOW CHART TIMELINE STEPS LEVEL I APPLICATION ADMINISTRATION ACCOUNTING ADMINISTRATION Informal Grant No Contentious Matters Arise Filed Releases LEVEL II Formal Proof of Will Contentious Matters Passing of Accounts DECISIONS IN SURROGATE CHAMBERS (Applications for Advice & Direction) LEVEL III DECISIONS AT TRIAL LEVEL IV APPEALS Trial Trial Includes Pretrial Procedure Trial DISCHARGE Court Order to Discharge