The Influence of Product Placement Prominence on

advertisement

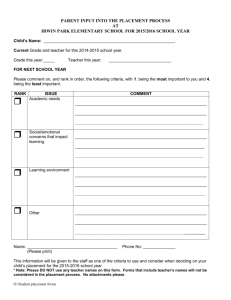

The Influence of Product Placement Prominence on Consumer Attitudes and Intentions: A Theoretical Framework Ben Kozary and Stacey Baxter, University of Newcastle Abstract Today’s marketers are looking for alternative approaches to communicate with their target population. One approach which has continued to receive attention over the past decade is product placement. While researchers have examined the effectiveness of product placements with respect to brand awareness and audience attitudes, little attention has been given to conative responses (such as purchase intention). This paper, therefore, seeks to develop a theoretical framework, illustrating the impact of ‘subtle’ and ‘prominent’ product placements on a consumer’s cognitive, affective and behavioural intentions. It is suggested that future research should extend the current literature, examining the impact of subtle and prominent product placement on purchase intention. Key Words: product placement, prominence, attitude, purchase intention The Influence of Product Placement Prominence on Consumer Attitudes and Intentions: A Theoretical Framework Background With traditional media now saturated with advertising messages, marketers are looking for alternative approaches to communicate with their target population. One approach which has continued to receive attention over the past decade is product placement (Balasubramanian, Karrh and Patwardhan, 2006; Gregorio and Sung, 2010; Law and Braun, 2000; Lehu and Bressoud, 2008; Van Reijmersdal, Neijens and Smit, 2009). Product placement refers to the usually purposeful integration of branded material into an entertainment medium, in a seemingly non-commercial manner, which is designed to influence the audience and result in commercial benefit (Balasubramanian, 1994; Chang, Newell and Salmon, 2009; Homer, 2009). Product placement is by no means a new promotional tool. The first reported product placement occurred in 1896, with the deliberate integration of Sunlight Soap by Unilever into several Lumière films (Gregorio and Sung, 2010). Placements continued to appear in Hollywood films throughout the 1920s (Hackley, Tiwsakul and Preuss, 2008); “[h]owever, product placement was neither a well-organized nor high-profile growth area until the late 1970s” (Balasubramanian, 1994, p. 33). Perhaps the most famous example of product placement occurred in the 1982 movie, E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, when E.T. followed Reese’s Pieces back to Elliot’s house (Balasubramanian, Karrh and Patwardhan, 2006; Chang, Newell and Salmon, 2009; Gupta and Lord, 1998; Law and Braun, 2000; Sung and Gregorio, 2008; Tsai, Liang and Liu, 2007). This placement, and the subsequent 65% increase in the sales volume of Reese’s Pieces (Gupta and Lord, 1998; Law and Braun, 2000) heralded the beginning of a product placement trend which continued to increase throughout the 1990s, and which now constitutes an industry worth more than $US4 billion (Balasubramanian, Karrh and Patwardhan, 2006). The practice of product placement is not, however, limited to motion pictures; with organisations also placing their products in television programs (for example, Pantene, M&Ms and Ruffles in Seinfeld, Cowley and Barron, 2008) and games (for example, Calvin Klein and Dell in Second Life, Barnes and Mattsson, 2008). Product placement has a wide range of promotional applications (Balasubramanian, 1994). Researchers have examined the effectiveness of product placement with respect to brand recall and recognition (for example, Gupta and Gould 2007; Gupta and Lord, 1998; Lord and Gupta, 2010; Yang and Roskos-Ewoldsen, 2007) and audience attitudes (for example, Cowley and Barron, 2008). No known studies, however, have focused on consumers’ conative responses (such as, purchase intention), which is believed to be a far more useful measure of product placement effectiveness (Van Reijmersdal, Neijens and Smit, 2009). To date, “films have been the most frequently studied vehicles for product placement” (Lord and Gupta, 2010, p. 190), with less attention given to other forms of entertainment. As such, this paper seeks to further our understanding of factors affecting the effectiveness of product placement in a commercial television setting. The paper draws upon literature to build a theoretical framework, illustrating the impact of ‘subtle’ and ‘prominent’ product placements on a consumer’s cognitive, affective and behavioural intentions. The paper will begin with a discussion of the application and growing prevalence of product placement in a commercial television context. Next, a theoretical framework is posited; and finally, testable propositions are developed in order to guide future research initiatives. Product Placement and Commercial Television There has been a rising need for, and prevalence of, product placement in response to the advent and increasing use of commercial skipping technology, for example, TiVo and Digital Video Recorders (Almond, 2007; Avery and Ferraro, 2000; Balasubramanian, Karrh and Patwardhan, 2006; Gupta and Gould, 2007; Sung and Gregorio, 2008; Yang and RoskosEwoldsen, 2007). Furthermore, “[t]he popularity and impact of traditional television advertising have been in decline in recent years as a result of increased costs […] since the late 1980s” (Avery and Ferraro 2000, p. 217). While it would be beneficial to discuss the contractual agreements between sponsors and the producers of television programs, these arrangements are proprietary and do not have to be publicly disclosed (Avery and Ferraro, 2000; Gupta and Lord, 1998). Nevertheless, conventional wisdom dictates that product placement deals are struck for the duration of a program’s season, as opposed to single episodes. For example, the Porsche brand is visible in the vast majority of Californication episodes – both within and across seasons. Given the attention that product placement has received from scholars (Van Reijmersdal, Neijens and Smit, 2009), as well as the legal considerations it has been afforded (Almond, 2007; Avery and Ferraro, 2000), product placement is now a legitimate, and frequently used marketing technique. For example, in a study conducted by La Ferle and Edwards (2006), it was revealed that, over the course of 105 hours of prime-time television, product placements were regularly featured, representing 49.5% of brand appearances. However, product placement is a complex concept, and extensive consideration must be given to several factors if it is to be effectively implemented. A Theoretical Framework This section presents the framework of factors that influence the overall effectiveness of product placement (Figure 2). The literature regarding the hierarchical structure of attitudes is reviewed, followed by a discussion of the elements of both prominent and subtle product placements, in which a theoretical model is presented. Attitude and Product Placement Attitude comprises three primary dimensions (cognition, affect and conation) which together, result in an individual responding favourably or unfavourably to phenomena they are exposed to (Ajzen, 1989). Perceptions of, and information about, the attitude object refers to an individual’s cognitive response (Ajzen, 1989). In a product placement context, cognition can refer to brand recognition and recall, and associated product learning (Balasubramanian, 1994). Affect refers to feelings about the attitude object (Ajzen, 1994). These ‘feelings’ are often referred to as persuasion in advertising (Balasubramanian, 1994), for example, a consumer’s feeling towards a brand is often indicative of how persuasive the advertising message (such as a product placement) is. On the other hand, “[r]esponses of a conative nature are behavioral inclinations, intentions, commitments and actions with respect to the attitude object” (Ajzen, 1989, p. 244). From a marketing perspective, this can refer to an individual’s purchase intention as a result of exposure to a product placement. The three dimensions do not operate independently of each other; rather, they are linked in a causal chain (Ajzen, 1989). That is, cognition imparts a direct influence on affect, which in turn leads to conative behaviours. As such, it is posited that learning and recall of brands impacts on the degree to which an individual is persuaded by product placements of those brands. Subsequently, the degree to which an individual is persuaded by product placements is directly related to that individual’s purchase intention of brands featured in the placements. This causal chain is illustrated in Figure 2; however, the overall attitude regarding placements is dependent on the prominence of the placement itself. A placement can typically be classified into one of two groups, those being: (1) prominent or (2) subtle. Prominence refers to “the extent to which the product placement possesses characteristics designed to make it a central focus of audience attention” (Avery and Ferraro, 2000, p. 225). Whilst a clear definition is not specified in the literature, it is suggested that placements deemed to be ‘prominent’ typically possess a combination of the following characteristics: a highly visible and/or large product, logo or other recognisable trait unique to that product, relative to the screen, high plot integration, repeated mentions, and long screen time duration. Figure 1 illustrates an example of a prominent and a subtle product placement. Figure 1: Prominent versus Subtle Product Placement : an example from Californication (2007), Apple Prominent Product Placement Main character integration Time on screen: 7 seconds Subtle Product Placement Used by an ‘Extra’ Time on screen: 2.5 seconds Models, or actors, can facilitate learning through product demonstrations in placement situations (Balasubramanian, 1994). Balasubramanian (1994, p. 38) suggests that placements “that reinforce product-use through models help individuals vicariously acquire brand preference and/or consumption behaviors that benefit the sponsor”. This reinforced use, through modelling, leads to explicit processing from audience members (Cowley and Barron, 2008) as they are aware of the placement. In turn, explicit processing results in high product learning and brand recall (Balasubramanian, 1994). While prominent placements often achieve high recall (Lord and Gupta, 2010), research has also shown that “[t]he higher the perceived prominence of a placement, the more negative the placement attitudes and beliefs” (Van Reijmersdal, Neijens and Smit, 2009, p. 433). The triggering of these negative attitudes can be attributed to the activation of the audience’s persuasion knowledge, and the fact that the placements are deemed to have obvious commercial intent (Cowley and Barron, 2008; Friedstad and Wright, 1994; Hackley Tiwsakul and Preuss, 2008; Van Reijmersdal, Neijens and Smit, 2009). Consequently, the placement would be ineffective in generating purchase intentions for the brand amongst audience members (as illustrated in Figure 2). Subtle product placements, on the other hand, lead to implicit processing of the placement, whereby “a consumer will not explicitly remember seeing the brand as a placement, but will report a more positive brand attitude as a result of the exposure” (Cowley and Barron, 2008, p. 90). Essentially, this means that whilst the viewer reports a lower awareness of the brand (in terms of recall and recognition), the viewer also does not perceive the commercial intent behind the placement. As such, subtle placements are considered to be more effective in generating purchase intentions for brands amongst audience members, relative to prominent placements (as indicated in Figure 3). Two theoretical models have been developed from the literature based on the modelling paradigm (Balasubramanian, 1994; Gregorio and Sung, 2010) and the persuasion knowledge model (Cowley and Barron, 2008; Friedstad and Wright, 1994; Hackley, Tiwsakul and Preuss, 2008; Van Reijmersdal, Neijens and Smit, 2009). These models refers to the level of placement prominence, and the corresponding effectiveness of that placement in terms of consumer recall, persuasion and purchase intention; as illustrated in Figures 2 and 3. Figure 2: The impact of prominent and subtle product placement on consumers, cognitive, affective and behavioural intentions Learning and recall + Prominent product placements + Awareness – Persuasion – Purchase intention Figure 3: The impact of subtle product placement on consumers, cognitive, affective and behavioural intentions Learning and recall Subtle product placements - Awareness + Persuasion + Purchase intention Conclusion and Directions for Future Research Product placement offers marketers an alternative approach for communicating with their target audience. The theoretical model presented in this paper illustrates a causal chain, from learning and recall, to persuasion, to purchase intention. As presented, the factors within this causal chain can be influenced by the nature of the placement: prominent or subtle. As such, it is evident that the nature of a placement can impact consumers’ cognitive, affective and behavioural processes. Prominent placements achieve high awareness, but result in negative consumer attitudes and thus low purchase intention; whereas the effects of subtle placements are typically opposite. Whilst previous researchers have examined the effectiveness of product placement in terms of brand recognition and recall, and consumer attitudes, no known studies have examined the impact of product placement on a consumer’s conative responses, such as purchase intention. It is therefore suggested that future research should extend the current literature, examining the impact of subtle and prominent product placement on purchase intention. The results of the proposed research will provide marketers and business decision makers with a further understanding of product placement, identifying whether it is a worthwhile promotional strategy in lieu of traditional media becoming saturated. Reference Ajzen, I., 1989. Attitude structure and behavior. In A.R. Pratkanis, S.J. Breckler & A.G. Greenwald (eds) Attitude, structure and function, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers, New Jersey, USA, 241-274. Almond, B.D., 2007. Lose the illusion: Why advertisers’ use of digital product placement violates actors’ right of publicity, Washington and Lee Law Review, 64(2), 625-670. Avery, R. J., Ferraro, R., 2000. Verisimilitude or advertising? Brand appearances on primetime television, The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 34(2), 217-244. Balasubramanian, S. K., 1994. Beyond advertising and publicity: Hybrid messages and public policy issues, Journal of Advertising, 23(4), 29-46. Balasubramanian, S. K., Karrh, J. A., Patwardhan, H., 2006. Audience response to product placements: An integrative framework and future research agenda, Journal of Advertising, 35(3), 115-141. Barnes, S., Mattsson, J., 2008. Brand value in Virtual Worlds: an axiological approach, Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 9 (3), 195 – 206. Change, S., Newell, J. Salmon, C. T., 2009. Product placement in entertainment media: Proposing business process models, International Journal of Advertising, 28(5), 783806. Cowley, E., Barron, C., 2008. When product placement goes wrong: The effects of program liking and placement prominence, Journal of Advertising, 37(1), 89-98. Friedstad, M., Wright, P., 1994. The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts, Journal of Consumer Research, 21(1), 1-31. Gregorio, F. D., Sung, Y., 2010. Understanding attitudes toward and behaviours in response to product placement: A consumer socialization framework, Journal of Advertising, 39(1), 83-96. Gupta, P. B., Gould, S. J., 2007. Recall of products placed as prizes versus commercials in game shows, Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising, 29(1), 43-53. Gupta, P. B., Lord, K. R., 1998. Product placement in movies: The effect of prominence and mode on audience recall, Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising, 20(1), 47-59. Hackley, C., Tiwsakul, R. A., Preuss, L., 2008. An ethical evaluation of product placement: A deceptive practice?, Business Ethics: A European Review, 17(2), 109-120. Homer, P. M., 2009. Product placements: The impact of placement type and repetition on attitude, Journal of Advertising, 38(3), 21-31. Hong, S., Wang, Y. J., Santos, G. D. L., 2008. The effective product placement: Finding appropriate methods and contexts for higher brand salience, Journal of Promotion Management, 14(1/2), 103-120. Kuhn, K. A. L., Hume, M., Love, A., 2010. Examining the covert nature of product placement: Implications for public policy. Journal of Promotion Management, 16(1/2), 59-79. La Ferle, C., Edwards, S. M., 2006. Product placement: How brands appear on television. Journal of Advertising, 35(4), 65-86. Law, S. Braun, K. A., 2000. I’ll have what she’s having: Gauging the impact of product placements on viewers, Psychology & Marketing, 17(12), 1059-1075. Lehu, J. M., Bressoud, E., 2008. Effectiveness of brand placement: New insights about viewers, Journal of Business Research, 61(10), 1083-1090. Lehu, J. M., Bressoud, E., 2009. Recall of brand placement in movies: Interactions between prominence and plot connection in real conditions of exposure, Recherche et Applications en Marketing, 24(1), 7-26. Lord, K. R., Gupta, P. B., 2010. Response of buying-center participants to B2B product placements, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 25(3), 188-195. Sung, Y., Gregorio, F. D., 2008. New brand worlds: College student consumer attitudes toward brand placement in films, television shows, songs and video games, Journal of Promotion Management, 14(1/2), 85-101. Tsai, M. T., Liang, W. K., Liu, M. L., 2007. The effects of subliminal advertising on consumer attitudes and buying intentions, International Journal of Management, 24(1), 3-14. Van Reijmersdal, E. V., Neijens, P., Smit, E. G., 2009. A new branch of advertising: Reviewing factors that influence reactions to product placement, Journal of Advertising Research, 49(4), 429-449. Yang, M., Roskos-Ewoldsen, D. R., 2007. The effectiveness of brand placements in the movies: Levels of placements, explicit and implicit memory, and brand-choice behaviour, Journal of Communication, 57(3), 469-489.