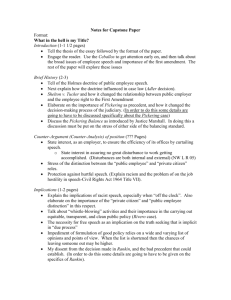

PICKERING v. BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOWNSHIP HIGH

advertisement