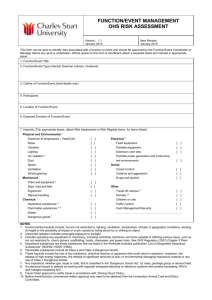

document

advertisement