A comparison of the argument structure of the German verb fragen

advertisement

UPPSALA UNIVERSITET

C-uppsats

Institutionen för lingvistik och filologi

Lingvistik C

VT 2012

A comparison of the argument structure of the German

verb fragen and the Faroese verb spyrja

The case of the ditransitive double accusative construction

Fredrik Valdeson

Handledare: Niklas Edenmyr

Abstract

This paper presents a study of the argument structure of the German verb fragen 'ask' and the

Faroese verb spyrja 'ask'. These two verbs can be used ditransitively, and both of them appear in a

double accusative construction (a construction in which both the direct object and the indirect

object are marked with accusative case), a ditransitive pattern that is relatively rare in both German

and Faroese. The main focus of this paper is to look at how frequent the double accusative

construction is, and to see if there are any other ways of coding the

ADDRESSEE

and the MESSAGE/TOPIC

(terminology borrowed from FrameNet), that will mark a clearer distinction between the two

objects. In addition to this, some other aspects (not necessarily ditransitive) of the argument

structure of these verbs are dealt with. The main findings are that the double accusative construction

is very unusual with both fragen and spyrja, that it seems possible to express the ADDRESSEE as some

kind of adverbial (together with a preposition), but that these cases are both quite rare and also a bit

doubtful, and that the most common use for both fragen and spyrja is to express the

clause (either a subordinate clause or a direct quote) and to leave the

ADDRESSEE

MESSAGE

as a

unexpressed. The

main difference between German fragen and Faroese spyrja is that fragen, to a much higher degree

than spyrja, may be used together with a reflexive pronoun.

2

Table of contents

Abstract.................................................................................................................................................2

1 Introduction....................................................................................................................................... 4

1.1 Purpose.......................................................................................................................................6

1.2 Terminology............................................................................................................................... 6

2 Background........................................................................................................................................6

2.1 Ditransitivity.............................................................................................................................. 7

2.2 German.......................................................................................................................................9

2.2.1 Case and ditransitive constructions....................................................................................9

2.2.2 The verb fragen................................................................................................................ 10

2.3 Faroese..................................................................................................................................... 11

2.3.1 Case and ditransitive constructions.................................................................................. 11

2.3.2 The verb spyrja................................................................................................................ 12

2.4 Introduction to FrameNet.........................................................................................................13

2.4.1 FrameNet terminology..................................................................................................... 13

2.4.2 FrameNet and the verb ask...............................................................................................14

3 Material and method........................................................................................................................15

3.1 Material.................................................................................................................................... 15

3.1.1 The Faroese corpus.......................................................................................................... 15

3.1.2 The German corpus.......................................................................................................... 16

3.2 Method..................................................................................................................................... 16

4 Results............................................................................................................................................. 17

4.1 Overview..................................................................................................................................17

4.2 Pure active clauses................................................................................................................... 20

4.2.1 Pure active clauses with fragen........................................................................................20

4.2.2 Pure active clauses with spyrja........................................................................................ 23

4.2.3 Comparison between fragen and spyrja...........................................................................27

4.3 Prepositional constructions...................................................................................................... 27

4.3.1 Prepositions used with fragen.......................................................................................... 28

4.3.2 Prepositions used with spyrja.......................................................................................... 29

4.4 Prepositional constructions expressing the ADDRESSEE..............................................................31

4.5 Constructions with two (non-agentive) nominal arguments....................................................33

5 Discussion........................................................................................................................................35

5.1 Comparison between fragen and spyrja.................................................................................. 35

5.2 The double accusative construction......................................................................................... 35

5.3 Ways of getting around the double accusative construction.................................................... 36

5.4 Final comments on ditransitivity............................................................................................. 37

6 Summary..........................................................................................................................................37

References.......................................................................................................................................... 38

3

1 Introduction

Within the theory of construction grammar, there is the idea of constructions operating as the basic

unit of language, and as such the sense of "construction" is as wide as possible, covering different

aspects of grammar, from lexical units through morphology to syntactic constructions (see Croft

2001:14 ff; Barðdal 2001:22-23). Linked to this theory is the Usage-based model, which stems from

a hypothesis assuming that constructions (be it either a word or a syntactic pattern) that are

frequently used will probably remain intact in a language, whereas those that occur less often are

more likely to dwindle out of use and eventually disappear (Croft 2001:28).

Following this idea, it is important to distinguish between constructions that are high in type

frequency and those that are high in token frequency. A syntactic construction that is high in type

frequency is instantiated by a large number of lexemes, whereas a construction high in token

frequency is instantiated by a narrowly limited amount of lexemes. The lexemes of the latter

construction are, however, most often relatively common (Barðdal 2001:31). It is also presumed

that a construction that is high in type frequency is more likely to be productive within the language

(Croft 2001:28).

With this perspective in mind, this paper presents an investigation of the usage of the German

verb fragen and the Faroese verb spyrja, which both fairly well correspond to English ask. What

makes these particular verbs interesting, is that although they are relatively frequently used, they

both exhibit the same kind of unusual morphological pattern, with the possibility of taking two

accusative objects at the same time (one denoting the content of the question and the other denoting

the person (or whatever) to whom the question is directed), setting them apart from the usual

ditransitive pattern of both German and Faroese, where one verb (traditionally called the direct

object) is in accusative case, with the other one (traditionally the indirect object) bearing dative

case.

In Barðdal (2001), construction grammar and the usage-based model are put into practice for the

analysis of various case patterns in Icelandic. She manages to confirm the notion that those patterns

that are instantiated by a higher number of lexemes are also more productive than less common case

patterns (Barðdal 2001:212). Another study, more closely related to the one carried out in this paper,

where construction grammar and the usage-based model are applied to empirical material, is found

in Silén (2008), where a comparison is made of the distribution between two alternating

constructions concerning the word ge 'give' in the Swedish spoken in Sweden with the same

phenomenon in the Swedish spoken in Finland (the alternation in this case is between a double

object construction and a construction with a prepositional object/adverbial).

4

For the verbs investigated in this study there is not, however, any clear distinction between two

alternating constructions. But assuming that constructions that are unusual in a language will tend to

be replaced by more common patterns, it might be hypothesized that the double accusative

construction of the verbs fragen and spyrja is not very common, and that, in order to express

clauses with these verbs in which there are two objects, some alternative construction, such as the

use of prepositions, might be used instead. This paper aims at investigating the overall frequency

and use of the double accusative construction with fragen and spyrja, and also looks at some

alternative constructions that these two verbs can appear in.

Another aspect, that is not dealt with further in this paper, but still deserves mentioning, is of the

historical development within the history of Indo-European languages from a case system to a

system with adpositions, a tendency that is shared between many of languages in this family. As

Germanic languages, both German and Faroese show a reduced case inventory compared to that of

Proto-Indo-European (see Hewson & Bubenik 2006:274-275). In addition to this, there also seems

to be a tendency towards minimalizing the number of different kinds of case patterns, also when it

comes to those case forms that still exist in the languages. An example of this is that verbs which

previously appeared with subjects in oblique case in Faroese, now increasingly join the more

prototypical pattern of subjects in nominative case (Barnes 1986/2001b). The same tendency can be

seen for the verbs fragen and spyrja, which both used to have a direct object in genitive case (see

section 2.2.2 below for German and section 2.3.2 below for Faroese), but now only appear with

objects in accusative case. Hewson & Bubenik point out that, in Indo-European, the accusative

usually represents "the goal, or goal of motion", whereas the genitive is used to denote "source or

departure" (Hewson & Bubenik 2006:17-18). The transition seen in fragen and spyrja, from

appearing with a genitive object to appearing with an accusative object seems therefore to, at least

in theory, change the meaning of the verb, which might in turn lead to other syntactic patterns, such

as the use of prepositions, taking over from the double-object construction in order to preserve the

meaning of the verb, and to keep the semantic distinction between the two objects intact. This

notion will be kept in mind as a possible explication for any alternative syntactic constructions that

might be found in relations to the verbs fragen and spyrja. (However, since no real historical

analysis will be carried out, it will not be possible to give any definite answer to whether the use of

any alternative constructions might have arisen as a consequence of case loss. This will have to be

the focus of future studies.)

5

1.1 Purpose

The main purpose of this paper is to look at the various argument structure constructions in which

the German verb fragen and the Faroese verb spyrja can appear. The focus is to see how common

the double accusative construction is with these two verbs, and to see if there are any other

strategies for coding the object-like arguments (such as the use of prepositions) that may help to

make a clearer distinction between these two arguments. In order to get a wider perspective, there

are also some comments on intransitive and monotransitive uses of fragen and spyrja, as well as a

short general investigation on how prepositions may be used in connection with these verbs.

1.2 Terminology

I do not in this paper make any attempt at approaching the question of what is and what is not a

direct or indirect object, but when talking about the double accusative construction of fragen and

spyrja I use, for the sake of convenience, the term indirect object for the recipient-/addressee-like

argument and direct object for the theme-/message-like argument. I generally use the terms

recipient and theme when discussing ditransitive patterns in general (which is mainly in section 2.1,

which gives some background to research on ditransitivity as a phenomenon) but when discussing

the particular verbs studied here I borrow the FrameNet terms

ADDRESSEE

and

MESSAGE/TOPIC,

which

hopefully makes a more accurate description of the activity of asking.

2 Background

A great deal of this paper deals with the concept of ditransitivity and the arguments involved in a

ditransitive clause. This section first gives an overview to some of the ways in which ditransitivity

can be described and analysed. After that, a short introduction is given to the ditransitive patterns of

German and Faroese, as well as some background information on the verbs fragen and spyrja.

Finally, there is a short presentation of the FrameNet project and the way in which I have applied

FrameNet terminology for this study.

6

2.1 Ditransitivity

A ditransitive clause is most simply described as a clause in which, apart from the subject, there are

two arguments, one encoding a theme-like argument, denoting something that is transferred to a

recipient-like argument (see Haspelmath 2005b). The prototypical ditransitive verb would then be

give, in which A (agent) gives B (theme) to C (recipient). A traditional view is to only consider

double-object constructions as ditransitive, where the theme argument is referred to as the direct

object and the recipient as the indirect object. This is a definition which to a large extent stems from

the descriptions of languages such as Latin, in which the theme of the ditransitive clause and the

patient of the transitive clause are treated alike, thus making it logical to group them together as

direct objects, whereas the recipient of the ditransitive clause is usually in the dative, and can be

described as an indirect object (see Dryer 2007:255). The terms direct object and indirect object are,

however, not treated equally among linguists. Givón (2001:142), for example, treats the first object

that follows after the verb as a direct object, regardless of its semantic role, whereas Hudson (1992)

argues, on formal grounds, that (at least for English) the first object is the indirect one (since the

second object is said to be the ”real object” (Hudson 1992:251)).

From a functional perspective (see e.g. Dryer 2007 & Malchukov et al 2007) the formal

properties of the arguments are not considered crucial for the definition of a ditransitive clause,

since there are several different ways in which to encode the arguments surrounding a verb like

give. Malchukov et al (2007) mention several ways in which the arguments of the ditransitive clause

can be encoded, treating case marking and the use of adpositions to mark the roles of the arguments

as basically the same strategy, considering it merely different kinds of flagging. In addition to this,

they also mention indexing (i.e. verb agreement, basically) and word order as methods that

languages use for indicating the basic functions of the ditransitive construction (Malchukov et al

2007:6).

Malchukov et al (2007) also refer to the various alignment types that exist cross-linguistically

within the ditransitive construction, distinguishing between indirective, secundative and neutral

alignment. Comparing the marking of the theme argument and the recipient argument of the

ditransitive clause with that of the patient of the transitive clause, these three different patterns

emerge. The indirective is the one that (like e.g. in Latin) treats the theme argument of the

ditransitive clause as equal to the patient of the transitive clause. Secundative alignment treats the

recipient of the ditransitive clause and the patient of the transitive as equal in terms of grammatical

marking (this seems to be the least popular alignment type among the world’s languages (see

Haspelmath 2005a:5)). Finally, neutral alignment does not explicitly distinguish between the roles

7

of patient, theme and recipient at all. What is interesting for the purpose of this paper, is that both

German and Faroese generally exhibit indirective alignment, apart from a few verbs in each

language that show neutral alignment. The verbs that are investigated in this study are of this

neutral alignment type, making them part of a marginal kind of ditransitive constructions in both

languages.

Haspelmath (2005b) distinguishes between three alignment types that are basically the same as

those mentioned above (although he does not take word order into account): the indirect-object,

(corresponding to indirective alignment) the secondary-object (secundative) and the double-object

(neutral) construction. He also has a category (”mixed”) for languages that use more than one of

these constructions. An example of this is English, in which there is an alternation between a double

object construction (as in He gave her an apple (my example)) and an indirect object construction

(He gave an apple to her). German is, however, considered only to have an indirective-object

construction (thus ignoring the double-object construction of fragen ’ask’).

There are, as we have seen, different opinions regarding how to treat those cases in which the

marking of the theme argument or recipient argument is done with an adposition. Malchukov et al

(2007) (see above) do not see any difference between case marking and adpositions, whereas Dixon

& Aikhenvald (2000) think of it the other way around. Firstly, they do not even distinguish any

ditransitive constructions at all. Instead, they talk about ”extended transitive clause types” (Dixon &

Aikhenvald 2000:3) (as opposed to ”plain transitive clause types”), in which a third argument is

added to the ”core” of the transitive clause. If, however, an argument is marked with a preposition,

it is considered a ”peripheral argument”, thus not being a part of the core. 1 Again, it does not lie

within the scope of this paper to make any statements concerning what is and what is not a core

arguments or to try to explain what defines a transitive clause. But it could be worth keeping in

mind that there are different views on ditransitivity. The use of prepositions as a replacement for

case marking (or the lack thereof) is also considered in the results section, and one of the main aims

of this paper is to discuss the double accusative constructions of German and Faroese in comparison

with the various prepositional uses that are found for fragen and spyrja.

Another issue that could be raised is whether to treat ditransitive constructions in which one of

the objects is a reflexive pronoun as purely ditransitive. Again, I do not try to make any theoretical

claims concerning this, but following e.g. Barðdal et al (2011) I will treat this kind of construction

as ditransitive, but when presenting my results I also make a clear distinction between clauses with

a reflexive recipient/addressee argument and those in which this argument is non-reflexive. This is

bound to be relevant, since the frequency of the reflexive construction is much higher with the

1 Also see Næss (2007:7-8) for some further discussion about these different ways of defining ditransitivity

8

German verb fragen than with the Faroese verb spyrja (see Table 4, section 4.2.3).

2.2 German

This section gives an introduction to the case system of German, with particular focus on

ditransitive constructions and the verb fragen.

2.2.1 Case and ditransitive constructions

German has a four-case system where, generally, the subject is in nominative case, and the

remaining three cases – accusative, dative and genitive – are used to denote objects of various kinds

(as well as taking part in various sorts of adverbial constructions) (Duden 1984:89). In a regular

transitive clause the direct object is in the accusative (see (1a) below), but there are several verbs

together with which the object of the transitive clause is expressed with dative or (extremely rarely)

genitive case (Freund & Sundqvist 2006:376-381). For ditransitive clauses the most common

pattern is to express the direct object with accusative case, and the indirect object with dative case.

In addition to this there are, however, three other patterns for clauses with two objects, namely

ACC-DAT

NOM-

(with the subject expressed in the nominative, the indirect object in the accusative and the

direct object in dative), NOM-ACC-GEN and NOM-ACC-ACC (Abraham 2006:122).

Examples (1a–c) show the pattern of a prototypical transitive clause, a prototypical ditransitive

clause and a ditransitive clause with two objects in the accusative, respectively:

(1) a. Transitive

Sie

liebt

she.NOM2 loves

den

Luxus. (Freund & Sundqvist 2006:374)

the.ACC luxury.ACC

'She loves luxury.'

2 Information about case is given whenever it is part of the argument structure of the verb in question. In both

languages investigated in this paper, but especially in German, there is no overt case marking for many of the words.

(In German, for example, case marking almost never shows up on the noun, but is usually expressed through the

definite article.) I do, however, indicate case also in these instances, as I consider it to be relevant for the discussion

of argument structure constructions. In order to prove that the right case form is given, the substitutional method

may be used, where a noun might be replaced by a personal pronoun, since these always exhibit case marking in

both German and Faroese.

9

b. Ditransitive: DAT-ACC

Der

Kellner

gab ihr

die

Speisekarte. (ibid:384)

the.NOM waiter.NOM gave her.DAT the.ACC menu.ACC

'The waiter gave her the menu.'

c. Ditransitive: ACC-ACC

Das

frage ich

that.ACC ask

dich. (ibid:387)

I.NOM you.ACC

'That's what I'm asking you.'

The double accusative construction (NOM-ACC-ACC) is comparatively small in German, and is only (or

mainly) instantiated by four verbs: bitten 'ask (for)', fragen 'ask', kosten 'cost' and lehren 'teach'.

(Freund & Sundqvist (2006:386-387). These four verbs are however relatively common, which

might explain the fact that the double accusative construction is still alive (see Introduction, section

1). Abraham (2006:123) makes the claim that "NOM-ACC-ACC is totally avoided and replaced by NOMDAT-ACC

in the substandards". Since my material is from a newspaper corpus, it is perhaps not

surprising that I have not found any of these "substandard"

NOM-DAT-ACC

constructions with the verb

fragen. Admittedly, I have not found that many NOM-ACC-ACC uses of it either, and it would of course

be of great interest to examine during what circumstances a NOM-DAT-ACC construction might be used

with this verb. (I should perhaps mention that Abraham (2006:143) does not consider the

ACC

NOM-ACC-

pattern to be ditransitive at all, with the explanation that only one of the objects of this

construction can adopt the subject position when passivized.)

2.2.2 The verb fragen

The verb fragen can, as we have seen, appear in a double accusative construction. This construction

is however strictly limited, in that the direct object can only be expressed as a neutral pronoun (see

example (1c) above). This ditransitive construction is however only one (and as will be seen, quite a

marginal one as well) of the constructions in which the verb can be used. The Oxford-Duden

German Dictionary (2001:310) lists both transitive and intransitive uses of the verb, as well as the

prepositional constructions nach etw. fragen 'ask/inquire about something' and jmdn. um

Rat/Erlaubnis fragen 'ask sb. for advice/permission'. They also mention the reflexive construction

with the pronoun sich, as in sich fragen, ob… 'wonder whether…'. Thus, we see that the German

verb fragen roughly corresponds to the English verb ask, but also stretches out to include meanings

10

such as 'inquire' and 'wonder'.

The diachronic aspect of ditransitive constructions and case patterns is not dealt with further in

this paper, but it might be of interest to know that fragen once appeared in a

NOM-ACC-GEN

frame

(Lexer 1922:352), rendering it parallel to modern Icelandic spyrja 'ask' (Barðdal et al 2011:18) (and

also to older stages of Faroese).

2.3 Faroese

This section gives an introduction to the case system of Faroese, with particular focus on

ditransitive constructions and the verb spyrja.

2.3.1 Case and ditransitive constructions

Faroese has a case system quite similar to that of German, with a nominative, an accusative, a

dative and a genitive case (although the latter is not much in use nowadays) (Thráinsson et al

2004:248). Nominative is the case usually used for denoting the subject, with the accusative being

somewhat default case for direct objects while the dative is most commonly associated with the

indirect object. Like in e.g. Icelandic, there are verbs that take oblique subjects (accusative or

dative), but these seem to be on their way out, instead being replaced by default nominative subjects

(ibid:253-257; Barnes 1986/2001b). There is also a number of verbs that select for a direct object

marked with dative case.

In Faroese there are only two case patterns for the ditransitive construction, with the NOM-DAT-ACC

(nominative case for the subject, dative for the indirect object and accusative for the direct object)

being by far the most common. There are only four verbs that act as an exception to this rule, and

instead appear in a

NOM-ACC-ACC

construction: biðja 'ask', kyssa 'kiss', læra 'teach' and spyrja 'ask'.

(Thráinsson et al 2004:263). (Note that with the exception of kyssa, the verbs in this group are

basically the same as three of the four verbs appearing in the German double accusative

construction (see section 2.2.1).) As has already been stated, the genitive seems to be on its way out,

and the case system appears to be undergoing great changes at the moment, with the nominative

taking over as a default subject case also for those verbs that used to take an oblique subject, and the

dative being used for the indirect object for almost all ditransitive verbs. The closely related

Icelandic, on the other hand, has preserved a number of different case patterns, of which all

probably existed in earlier Faroese (see Barðdal 2007). Looking ahead, it will thus be interesting to

11

see if (or how long) the NOM-ACC-ACC will survive.

Examples (2a-c) show the pattern of a prototypical transitive clause, a prototypical ditransitive

clause and a ditransitive clause with two objects in the accusative, respectively:

(2) a. Transitive

Jógvan

las

bókina. (Thráinsson et al 2004:236)

Jógvan.NOM read book.the.ACC

'Jógvan read the book.'

b. Ditransitive: DAT-ACC

Hon

gav

gentuni

telduna. (ibid:262)

she.NOM gave girl.the.DAT computer.the.ACC

'She gave the computer to the girl.'

c. Ditransitive: ACC-ACC

Tey

spurdu meg

they.NOM asked

ein

spurning. (ibid:263)

me.ACC a.ACC question.ACC

'They asked me a question.'

2.3.2 The verb spyrja

The ditransitive use of the verb spyrja differs slightly from that of German fragen, since the direct

object is (almost) always a cognate object (term borrowed from Givón 2001:132) – spurning –

which simply means 'question' (Henriksen 2000:79). (Remember that in German, fragen could

(basically) only be used with a neutral pronoun meaning 'that'.) Just like in German, however, the

ditransitive use of spyrja is, as is shown in this paper, not very common at all. The verb can appear

in a number of constructions that, to quite a large extent, correspond to those also found in German,

with its basic meaning being that of English 'ask'. Young & Clewer (1985:547) list the prepositional

uses with eftir and um: spyrja ein eftir 'ask someone how…is getting on', spyrja um eitt 'ask

(questions) about something'. (These prepositions roughly correspond to German nach and um.)

Spyrja can also have the meaning of 'be informed', 'get to know', which sets it apart from fragen.

Listed under the same entry in both Young & Clewer (1985) and Føroysk orðabók (1998) is the

derived so-called middle form spyrjast. This word has the meaning of 'come back', 'reappear'

("about a person who, or a thing which, has disappeared" (Young & Clewer 1985:547)), and is thus

12

clearly set apart from the basic word spyrja. (When discussing my results I do not delve into the

uses of spyrjast, since it falls out of the scope of this paper.) As in German, there is also a reflexive

construction, with the pronoun seg (sjálvan) being used as indirect object. This is, however, not

mentioned in the dictionaries I have looked in, and as is seen in the results section this reflexive

construction is by far more marginal in Faroese than it is in German.

2.4 Introduction to FrameNet

When analysing my results, I partly rely on the model for studying lexical meaning devised by

Fillmore and his companions within the FrameNet project. In this section I briefly explain what

FrameNet is and how it works (for more detailed information, see Fillmore et al 2007 and Atkins et

al 2007).

2.4.1 FrameNet terminology

The aim of FrameNet is to capture the meaning of a word by looking at the various contexts in

which it appears. Each different sense of a word is called a lexical unit, and each lexical unit evokes

a specific frame, where those words that are required in order to give the word its appropriate

meaning are known as frame elements (Fillmore et al 2007). Each frame has its own name, as have

the frame elements. To illustrate this, Fillmore et al (2007) use the Transfer frame, whose frame

elements are DONOR, THEME and RECIPIENT, where the DONOR is in possession of the THEME, which is then

transferred to the RECIPIENT. This frame can, for example, be evoked by the verb give.

In this example, the frame elements correspond quite well to the traditional grammatical

relations of subject, indirect object and direct object (see e.g. Blake 2001: ch. 1) and the semantic

roles of agent, patient and dative (see e.g. Givón 2001:107,142). The frame elements of FrameNet

are, however, more complex and more specific to the frame. Thus, both adverbials and subclauses

can appear as frame elements, and the frame elements of give are preserved when we turn the

perspective around and look at the verb receive, in which the

DONOR

RECIPIENT

receives the

THEME

from the

(Fillmore et al 2007:238).

As we have seen, several words can appear in the same frame, and the same word can also

appear in different frames. In this way FrameNet can show and describe the polysemy of one single

word, as well as the (near) synonymity of the different words that appear in the same frame.

FrameNet also distinguishes between so-called core and non-core frame elements (see Atkins et

13

al 2007:267). The core elements are those that are required in order to give the word its meaning

and that, in a sense, define the frame (as with the frame elements

DONOR, THEME

and RECIPIENT for the

Transfer frame). In addition to these basic elements, there are however others that can be added,

without really changing the meaning of the word, such as

MANNER

(the way in which something is

given) or REASON (the reason for which something is given). To complicate the matter, core elements

can sometimes be omitted, if the circumstances allow (Atkins et al 2007:269). In my material, this

is illustrated by those examples in which only either the addressee or the theme is present (and

where the element that is not explicitly expressed is supposedly known through the context).

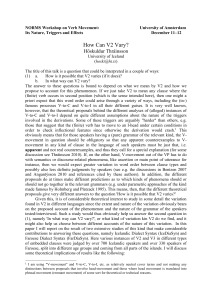

2.4.2 FrameNet and the verb ask

The verbs that are investigated in this paper, German fragen and Faroese spyrja, both to a large

extent correspond to the English verb ask. In English, ask can evoke two different frames, the

Request frame and the Questioning frame. (FrameNet: Request; FrameNet: Questioning.) In the

discussion (section 5) I compare the results from investigation on the verbs fragen and spyrja to see

how well they fit into these two frames.

The core elements of the Questioning frame are the

is directed), the

MESSAGE

ADDRESSEE

(the person to whom the question

(the question or the content being asked), the

question), as well as, in many cases, the

TOPIC

SPEAKER

(who asks the

(which in English usually appears as a so called PP-

complement, i.e. noun phrase headed by a preposition, in this case usually about, (you ask someone

about something).) (FrameNet: Questioning.)

For the Request frame, the core elements are basically the same, apart from the fact that there is

no

TOPIC

ADDRESSEE

element within this frame (but there is still the

SPEAKER

who requests something, the

to which the request is directed, and the MESSAGE which tells the content of the request). In

this frame there is also a core element known as the

MEDIUM

(through which the request is

transmitted), in English usually a PP-complement (e.g. "...on television", "...in the papers").

(FrameNet: Request.)

The core elements that are the main focus of this study are the

ADDRESSEE

and the

MESSAGE,

since

these are the elements that can appear in the shape of objects, and thus constitute the double

accusative construction. Also the

TOPIC

is of interest, since a lot of the prepositional uses of fragen

and spyrja are similar to that of English ask about. (In my material, the MESSAGE and the TOPIC never

appear together in the same construction, and for the sake of simplicity I often treat them as a

MESSAGE/TOPIC

unit, since they both, in a sense, serve the purpose of expressing the content of he

question.) In English, the

ADDRESSEE

is usually a regular NP but can also be instantiated by a PP

14

Complement (usually a kind of directional adverbial) (FrameNet: Questioning), and the frequencies

of objects vs. prepositional constructions for the

section in this paper. The

MESSAGE

ADDRESSEE

is one of the main issues of the results

is described as usually taking ”the form of a direct quote or an

embedded question with a verb target” (ibid). In this study, I also take NP's as being able to denote

the MESSAGE, in those cases where they refer to the content being asked.

Despite being referred to as core elements, both the

ADDRESSEE

and the

MESSAGE

can be omitted

(this is true for both German and Faroese, as well as English). It actually turns out that for German

and Faroese, leaving out the ADDRESSEE is more common than explicitly stating it (see Tables 2 and 3

in section 4.2 below).

3 Material and method

3.1 Material

In order to obtain enough natural language material to carry out a quantitative study, I have used

material from two newspaper text corpora, one for German and one for Faroese. Considering the

fact that German is a much more widely spoken language than Faroese, it is not surprising that the

number of German corpora available greatly outnumbers that of Faroese. Thus, the nature of the

Faroese corpus that I was able to obtain also had to dictate the conditions for the German one (and

is therefore presented first).

3.1.1 The Faroese corpus

The Faroese corpus is the Føroyskt TekstaSavn ('Faroese Text Collection') (FTS), obtainable

through Språkbanken (Gothenburg University). The corpus consists of all articles published during

1998 in the Faroese newspaper Dimmalætting, which at the time came out five days a week,

Tuesday-Saturday (Hansen 2005). The articles include both those written by journalists and those

that have been written and sent in by readers. (The number of articles written by readers is relatively

high, amounting to 767 out of 2853 (ibid). This could be kept in mind while looking at the results,

since many of these articles/letters address other readers, making the use of the accusative form of

the second person singular – teg – higher than it might otherwise have been.) The corpus explicitly

omits entries such as advertisements and announcements, with the exception of four weeks (about

20 issues), in which also the private advertisements were included (ibid). When dealing with my

15

results, I have omitted those case where it obvious that the examples have been taken from

advertisements, since the word spyrja is used quite extensively in these (such as when people who

are interested in buying something are requested to call a specific number and ask for a specific

person).

3.1.2 The German corpus

The German corpus is a small sample from the DWDS (Digitales Wörterbuch der deutschen

Sprache 'Digital dictionary of the German language'). This corpus consists of several newspapers,

as well as novels and other kinds of prose (DWDS). In order to get data that would be relatively

comparable to the Faroese corpus, I have chosen one newspaper, the Berliner Zeitung, and

narrowed my material down to only cover the entries from 1998, thus having both of the

investigated corpora representing the same space of time.

3.2 Method

In order to get a result that I was able to handle, I have only looked at five hundred instances each

of the verbs, counting backwards (thus taking the last 500 entries from the year 1998), since for

some reason this was the default setting of the German DWDS corpus. With the DWDS it is

possible to simply search for a word in its uninflected form and still obtain all entries of the word in

all its different forms. The verb fragen generated 3530 entries, which means that I have merely

studied about 15% of all the entries for fragen from this year. To search the FTS for all inflected

forms of spyrja, I had to search for the different forms individually. The FTS, however, gives you

the opportunity to search for all the words that begin with a specific letter constellation, which made

it possible to get all instances of spyrja by doing three different searches in the corpus: spyr%

(where % means ”words that consist of or begin with these letters”) for the forms spyrji, spyrt, spyr,

spyrjandi and spyrið, spur% for spurdi, spurdu, spurd and spurdur, and spurt for spurt. All in all

these searches rendered 1513 entries, which means that my results reflect about 33% of the overall

material in the corpus.

For both fragen and spyrja, a number of the original 500 entries were later omitted, for reasons

explained in section 4.1 below. The entries that remained have then been categorized for different

aspects, e.g. transitive uses and prepositional uses. This categorization is also accounted for in

section 4.1.

16

4 Results

The results are presented in several steps, starting with an overview of the whole material, followed

by a number of in-depth studies where the aim is to highlight those constructions concerning fragen

and spyrja that are relevant for this paper. For each language a number of different comparisons are

made, such as the percentage of ditransitive as opposed to monotransitive or intransitive clauses.

The number of clauses taken into account for each individual comparison (of which most are

presented in tables) will therefore differ, and when percentile measures are given, they often do not

refer to the entire material, but only to a particular subset thereof, and in these case it should be

obvious on what grounds these subsets have been made.

The main focus of this study is to find out how frequent the ditransitive double accusative

construction is in connection to the German verb fragen and the Faroese verb spyrja, and to see if

there are any other ways to express the

ADDRESSEE

and the

MESSAGE

than as direct objects in

accusative case. The idea is that this can be done by replacing one (or both) of the objects of the

double accusative construction with a prepositional phrase, thus taking the form of an adverbial.

In the first overview of the material (see Table 1, section 4.1), I have included instances where

the verbs occur together with a particle, as well as passive/participle constructions, in order to get a

clearer perspective on the whole range of how the verbs are used. Apart from that however, the

focus will be on active in- mono- and ditransitive uses of the verbs (which I have lumped together

as pure active clauses), and the uses of a preposition to mark one of the core elements, thus

comparing and discussing different kinds of "flagging" (see section 2.1.)

Prepositional constructions generally pose a problem, since it always has to be decided whether

we are dealing with a core element (in FrameNet terms) or some kind of non-core adverbial.

(Usually, however, these different uses are in practice relatively easy to tell apart.) Section 4.4

shows the examples I have found of prepositional constructions used to express the

ADDRESSEE.

Most

likely, all of these examples can be questioned, since we might just as well be dealing with

adverbials merely expressing the location or direction of the question. However, I hope that my

analysis can still put a little perspective on the ditransitive construction of German and Faroese.

4.1 Overview

First of all, Table 1 shows how many instances of each verb that have eventually been included in

the investigation. The material has been divided into four categories, based on the how the verbs

behave. The pure active clauses (admittedly not very good term) are the ones where the verbs are

17

used either in-, mono- or ditransitively (with "transitive" here used in the formal sense).

The category preposition only includes those clauses where the

MESSAGE

or

TOPIC

is expressed

with a prepositional construction, such as in the Faroese example (3). (Note that instances where a

preposition is used to denote the

ADDRESSEE

are not taken into account here, but are dealt with in

section 4.4.)

(3) Tú

kundi spyrja hann

you.NOM could ask

um

him.ACC

okkurt

fjall...

about some.ACC

mountain.ACC

'You could ask him about some mountain...'

Particle constructions are given a category of their own, since the particle itself usually adds

meaning to the verb that lies out of the original scope of the verb. Because of this difficulty in

explaining the meaning of a verb and particle combination (and also because of the fact that particle

verbs might be considered verbs in their own right) I have chosen not to study these verbs any

further, but only include them in this first overview. In (4a–b) examples are given of a particle

construction in German and Faroese, respectively.

(4) a. Wir

fragen nicht als Aasgeier

we.NOM ask

not

as vultures.NOM

nach,

PARTICLE

sondern aus

('after') but

Interesse.

out-of interest

'We do not inquire as vultures, but out of interest.'

b. ...tí-at

landsstýrismaðurin

hevði útnevnt

because the.member-of-govertnment.NOM had

nevndina

uttan

tveir prestar

appointed two clergymen in this.ACC

at spyrja Prestafelagið

the.committee.ACC without to ask

í hesa

the.clergymen-associtaion.ACC

eftir.

PARTICLE

('after')

'...because the member of government had appointed two clergymen for this

committee without asking the association of clergymen.'

Finally, the participle/passive category contains those occurrences of the past participle that are

either used to construct passive sentences (in which one of the objects, in this case mainly the one

expressing the MESSAGE, is moved into subject position) or used as adjectives, either predicatively or

attributively. The form of the past participle may, in both German and Faroese (as well as in

English) also be used to form the perfect tense. These clauses are not included in the

'participle/passive' category, since they do not share the adjectival behaviour of the usages

18

mentioned above. (Also note that both languages can form present participles (roughly

corresponding to the English progressive form). Although these participles also have an adjectival

aspect, they do not alter the syntactic structure of the corresponding active clause, i.e. if an active

clause is reshaped and the verb replaced by a present participle, the syntactic and semantic

properties of the participants will remain intact, the subject will remain in subject position, the

direct object in direct object position etc.) The examples included in the participle/passive category

will also be left aside for the remainder of this study, due to the limited amount of space in this

paper, but for the sake of illustration, examples form German and Faroese, respectively, are given in

(5a–b).

(5) a. Wir

sind nie

gefragt worden.

we.NOM are never asked

been

'We were never asked.'

b. Men teir

blivu spurdir uppaftur aftaná...

but they.NOM were asked

again

afterwards

'But they were asked again afterwards...'

Table 1 illustrates the size of the investigated material, and not too many implications should be

drawn from the figures in it. Among occurrences that were not included in the material are, for

example, when one and the same clause occurs more than once (in exactly the same context). (The

reason why such duplicates exist might be that the same sentence occurs both on the front page as

well as in an article inside the newspaper.) This accounts for basically all 15 clauses that were taken

away from the German sample. The reason why the Faroese material is so much smaller is, partly,

that there were more duplicates in the Faroese corpus. Also, all instances that were obviously part of

advertisements were taken out (see section 3.1.1 above), as well as a few instances of the expression

Spyr bara 'just ask', which was the name of a Faroese TV show in 1998. Finally, the occurrences of

the mediopassive form spyrjast are not included, since this is arguably a verb of its own, with a

meaning that ranges quite far from that of spyrja (see section 2.3.2).

19

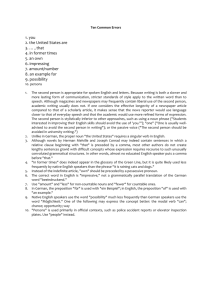

Table 1: Overview of the whole material (pure active includes instances of formally in-, mono- and

ditransitive uses)

fragen

spyrja

Pure active

340

258

Preposition

44

48

11

26

90

104

485

436

Particle*

Participle/passive

*

Total

4.2 Pure active clauses

In this section the distribution of the pure active clauses of fragen and spyrja are presented. (In this

paper, direct object refers to an object in accusative case expressing the

MESSAGE,

and indirect object

to an object in accusative case expressing the ADDRESSEE.)

4.2.1 Pure active clauses with fragen

Table 2: Distribution of pure active uses of fragen

NP as direct

object

Clause as direct

object

No direct

object

Total

Indirect object

5

58

9

72

Indirect reflexive

4

85

1

90

No indirect object

7

166

5

178

16

309

15

340

Total

* This category is not further dealt with in this paper.

20

Table 2 shows how the pure active clauses in the German material are distributed, and examples

(6a–i) show examples of all the nine categories of clauses found in Table 2, with (6a–c) illustrating

the examples with an indirect object, (6d–f) those with an indirect reflexive (i.e. where a reflexive

pronoun is used instead of a "proper" indirect object), and (6g–i) showing examples of clauses with

no overtly expressed indirect object.

(6) a. Indirect object + NP as direct object

Niemand

würde mich

das

fragen,

no-one.NOM would me.ACC that.ACC

ask,

wenn ich ein Buch über Massenmörder

if

I

verfaßt hätte.

a book about mass-murderers written had

'No one would ask me that, if I had written a book about mass-murderers.'

b. Indirect object + clause as direct object

Sie

fragte den

Hai,

warum er das getan hätte...

she.NOM asked the.ACC shark.ACC, why

he that done had

'She asked the shark why he/it had done that...'

c. Indirect object + no direct object

Aber ihn

but

fragt ja

keiner.

him.ACC asks (yes) no-one.NOM

'But no-one asks him, (of course).'

d. Indirect reflexive + NP as direct object

Das

fragt

that.ACC asks

sich

mit dem Publikum auch Bruno Grassini...

himself.ACC with the audience also Bruno Grassini.NOM

'That is also what Bruno Grassini asks himself, together with the audience.'

21

e. Indirect reflexive + clause as direct object

Dazu

fragte man

additionally asked

so viel

sich,

INDEF.NOM

woher

beim Kasselerbraten

oneself.ACC, from-where by-the kasseler-frying

Sauce kommt.

so much sauce comes

'In addition to that, one asked oneself ('it was asked'), from where, when frying the

kasseler, all that sauce comes out.'

f. Indirect reflexive + no direct object

Ich hoffe, es gibt noch viele

Redakteure,

I

editors

hope, it gives still

die

many

sich

beharrlich

durch

alle Instanzen

fragen...

who.NOM themselves.ACC persistently through all official-channels ask

'I hope there are still many editors who persistently ask themselves through all the official

channels...'

g. No indirect object + NP as direct object

Dort können wir

there can

alles

fragen, was uns bewegt.

we.NOM everything.ACC ask,

that us

moves.

'There we can ask everything that concerns us.'

h. No indirect object + clause as direct object

Ja, könnt ihr mich nicht in Ruhe fliegen lassen? fragte die

yes can

you me

not

in peace fly

let

asked the.NOM leader-goose.NOM

'Yes, can't you just let me fly undisturbed? asked the leader-goose.'

i. No indirect object + no direct object

Aber Maja

but

fragt nicht nur...

Maja.nom? asks

not

only

'But Maja does not only ask...'

22

Leitgans...

(6a) is an example of the double accusative construction, with both objects in accusative case. As

expected (see section 2.2.2) the direct object is instantiated by a neutral pronoun – das 'that'. Out of

the five occurrences in my material of this construction, three clauses contained this word as its

direct object, the other two having the words was 'that'/'what' and alles 'everything', both fitting into

the description of neutral pronouns. It is also obvious that the double accusative construction is

quite rare in my sample, with a total of five occurrences, which mounts up to just a bit over one per

cent of all occurrences of fragen.

The nature of the direct object is, in my sample, slightly more varied in a few cases where there

is no indirect object present. Here we find the words Spannenderes 'something more exciting' and

Witziges 'something witty', which could both be described as nominalized adjectives (though at least

they are both neutral, and may, perhaps, due to their inflectional behaviour be seen as more

pronominal than nominal). This must, however, be seen as a marginal extension of what is possible

for a direct object of fragen. It should also be pointed out that both these examples are from the

same newspaper article, and could possibly be seen as an artistic contribution by the author.

The most common use, by far, concerning the verb fragen is to have its

MESSAGE

appear as a

direct object-like clause. Clause, in the sense I use the term here, includes both subordinate clauses

and direct quotes, including a few cases where the question is in a foreign language, as well as

clauses that lack an explicit finite verb. The latter means that a clause can, in some cases, consist of

only one word, and maybe a word like utterance would be more appropriate than clause. However,

these occurrences are relatively rare, and as I have not seen any reason for treating clause and

utterance as two separate categories, the term clause still describes fairly well what is indicated

here. (The wide scope of this category (clause as direct object) might, however, to some extent

explain why it is also so heavily represented in my material.)

4.2.2 Pure active clauses with spyrja

Table 3 presents the distribution among the Faroese pure active clauses. As with fragen, we see

again a clear tendency towards constructions with a direct object expressed as a subordinate clause

or a direct quote, as well as a preference for not explicitly stating an indirect object. When

compared with the German results, the main difference seems to be that, in Faroese, the verb spyrja

is usually not used together with a reflexive pronoun, but that, on the other hand, the intransitive use

of the verb is relatively common. (The Faroese reflexive construction is a rather complicated issue,

which is dealt with in more detail further down in this section.)

23

Table 3: Faroese pure active clauses

NP as direct

object

Clause as direct

object

No direct

object

Total

Indirect object

1

58

19

78

Indirect reflexive

03

13

0

13

No indirect object

3

132

32

167

Total

5

203

51

258

Examples (7a–i) illustrate the various pure active construction types found in the Faroese material.

(The examples have been numbered so that they can be easily compared with the corresponding

German ones in section 4.2.1. This means that an example (7f) does not exist, since there is no

occurrence in my material of an indirect reflexive pronoun appearing in a construction in which

there is no direct object. There is one potential occurence of an indirect reflexive pronoun occuring

together with an NP as the direct object (see footnote), but this example has to be considered

doubtful, and is thus not included in the statistics, and following this there is no example (7d) in the

list of examples below.)

(7) a. Indirect object + NP as direct object

...kundi gitni

sálargreinarin

Alfred Adler spyrja vitjandi "sjúklingin"

could renowned the.psychotherapist.NOM Alfred Adler ask

visiting the.patient.ACC

skynsama spurningin...

sensible

the.question.ACC

'...the renowned psychotherapist Alfred Adler was able to ask the visiting "patient" the

sensible question...'

3 There is one example in my material with an indirect reflexive and what could be understood as an NP as direct

object. The example is, however, not a very good one, since the direct object – sum – is a word that cannot be

inflected in any way. It is therefore difficult to say if this word should be treated as a relative pronoun bearing some

kind of invisible accusative case marking, or simply as a subordinator bearing no case marking at all and as such not

even being a part of the argument structure of the verb. For the sake of illustration, this is example is given (as (7d)

below:

(7) d. Hetta vóru spurningarnir, sum

leiðarar

kring heimin

spurdu seg sjálvan...

these were the.questions that.ACC? leaders.NOM around the.world asked them-selves.ACC

'These were the questions that leaders around the world asked themselves.'

24

b. Indirect object + clause as direct object

Tað er sum at spyrja revin,

that is like to ask

um hann hevur etið

the.fox.ACC if

he

has

gásina...

eaten the.goose

'That is like asking the fox if he has eaten the goose.'

c. Indirect object + no direct object

Fyrst geva teir

loyvi

uttan

at spyrja nakran.

first give they permission without to ask

anyone.ACC

'First they give permission without asking anyone.'

e. Indirect reflexive + clause as direct object

Og eg

havi spurt meg

sjálva

er hetta átrúnaður, ella er hetta politikkur?

and I.NOM have asked me.ACC self.ACC is this

faith

or

is this

politics

'And I have asked myself, is this faith or is this politics?'

g. No indirect object + NP as direct object

Hann

visti nógv og

spurdi viðkomandi spurningar...

he.NOM knew much and asked relevant

questions.ACC

'He knew a lot and asked relevant questions...'

h. No indirect object + clause as direct object

Dagin

eftir spyr hann: "Er tað í-morgin

the.day after asks he.NOM

is

it

enn?"

tomorrow yet

'The next day he asks: "Is it tomorrow yet?"'

i. No indirect object + no direct object

Vit

spyrja og

we.NOM ask

svara, hugsa og droyma, flenna og signa...

and answer think and dream laugh and bless

'We ask and answer, think and dream, laugh and bless...'

The double accusative construction is, as the table shows, extremely rare with spyrja. In my sample,

I only found one example (7a), and in this example, the direct object, skynsama spurningin 'the

sensible question', is actually followed by a direct quote revealing the content of the question. Thus,

it could have entered the category Clause as direct object as well, but I have chosen to consider the

25

noun phrase to be the main direct object (where the clause might possibly be seen as attributive).

As was expected from the background information on Faroese (see section 2.3), the content of a

noun phrase appearing as a direct object is a cognate object, simply meaning 'question'. One of the

five instances of NP as direct object did however have the word meira 'more' in this position, a

word that I have chosen to include in the NP category, although it might also be referred to as an

adverb. This exception suggests that other words may be used to denote the content of the question

than just the word spurning, but this is, in any case, a marginal extension of the original behaviour

of this construction.

The reflexive pronoun in Faroese exists in two different varieties, the "simplex reflexive

pronoun" seg and the "complex reflexive pronoun" seg sjálvan (Thráinsson et al 2004:199-20). The

function of the Faroese reflexive has been most thoroughly discussed by Barnes (1986/2001a), and

it is not always possible to predict, in a clause consisting of a main clause and a subordinate clause,

whether the reflexive seg refers to the subject of the main clause or the subject of the subordinate

clause. In my sample I have found two such ambiguous examples, illustrated by (8):

(8) Seinni í greinini

later

greiðir

Jóan Karl frá,

at

um Landsstýrið

in the.article explains Jóan Karl from that if

hevði spurt seg,

hevði hann sagt, at

had

had

asked

REFL.ACC

fullkomuliga óegnað

he

skipið

government.the. NOM

var og er

said that ship.the was and is

sum vaktarskip.

completely unsuitable as

guard-ship

'Later on in the article Jóan Karl explains that if the Government had asked him, he would

have said that the ship was and is completely unsuitable as a guard ship.'

This sentence will not make sense unless you take seg as referring back to Jóan Karl, i.e. the

Government is not supposed to ask itself, but to ask Jóan Karl about his opinion on this ship. Thus,

despite the fact that this formally is a reflexive pronoun, I have chosen to classify this as indirect

object rather than indirect reflexive.

It must also be kept in mind that the German reflexive construction sich fragen 'to ask oneself'

may also translate as 'to wonder', whereas the Faroese dictionaries I have consulted did not suggest

any similar meaning for the reflexive construction with spyrja.

26

4.2.3 Comparison between fragen and spyrja

Table 4 shows a comparison of some of the major statistical differences between the results from

the German and the Faroese corpus. As has already been stated, the German verb fragen appears

with a reflexive pronoun much more often than does Faroese spyrja. This reflexive usage is, in the

German sample, even more common than are the instantiations of the verb with a "proper" direct

object. What German and Faroese seem to have in common is that, in most cases (more than 50 per

cent of the examples I have looked at) there is not considered to be any need to explicitly state the

MESSAGE.

This tendency is, however, stronger with Faroese than with German, and it might also be

worth remembering that, in Faroese, it appears to be more common also to omit the direct object,

thus rendering what we might call an intransitive use of the verb spyrja much more common than

with fragen.

Table 4: The nature of the ADDRESSEE in clauses where the MESSAGE is explicitly instantiated by either

an NP or a clause.

fragen

spyrja

Tokens

(NP+clause)

Percentage

Tokens

(NP+clause)

Percentage

Indirect object

63 (5+58)

19,4 %

59 (2+58)

28,5 %

Indirect reflexive

89 (4+85)

27,4 %

13 (0+13)

6,3 %

Not instantiated

173 (7+166)

53,2 %

135 (3+132)

65,2 %

325

100 %

207

100 %

Total

4.3 Prepositional constructions

This section present just a brief overview of the prepositions used to denote either the

TOPIC

MESSAGE

or the

argument of fragen and spyrja. A more detailed investigation of the semantics of the

prepositions used in connection with these verbs (and how this might relate also to the meanings of

the non-prepositional uses) would of course be appreciated. In the results presented here, I simply

list which prepositions are used, and briefly try to capture the meaning of these.

27

For both fragen and spyrja there are, in my material, two prepositions that can be used to

distinguish the

MESSAGE/TOPIC

(German nach and um, Faroese eftir and um), and they appear to be

used rather similarly in the two languages. We might however note that Faroese seems to favour

prepositional constructions to a much higher degree than German does, and also that the relative

frequency between the two prepositions varies between the languages.

4.3.1 Prepositions used with fragen

Table 5: MESSAGE/TOPIC argument of fragen instantiated with a preposition.

Preposition: nach

Preposition: um

Total

Indirect object

9

2

11

Indirect reflexive

1

0

1

No indirect object

32

0

32

Total

42

2

44

Looking first at the German examples, we find the prepositions nach and um. The preposition um

only appears twice in my sample, both in the same kind of sentence, where somebody asks someone

else for advice. Applying a FrameNet perspective to this, um is used here to denote the

MESSAGE

within the Request frame (cf. the non-prepositional uses presented above, where the direct object

could only be the MESSAGE within the Questioning frame).

The preposition nach is a bit more complex, with at least two easily distinguishable meanings, as

shown in examples (10a–b) below. (10b) ought to be interpreted as having a meaning fairly similar

to that of um, illustrated by the fact that both examples would require the English translation 'ask

for', whereas example (10a) shows a usage of the preposition nach that would rather be translated as

'ask about'. In FrameNet terms, the preposition nach is in this way used to mark a

TOPIC

argument

within the Questioning frame. We might thus conclude that when an argument with a preposition is

used in connection with fragen instead of just a simple direct object, there is either a slight shift in

the meaning of the verb (from Questioning to Request), or a change in the nature of the argument

(from MESSAGE to TOPIC).

28

(9) Preposition um generating the meaning of 'request'

Ich

fragte Freunde

um Rat.

I.NOM asked friends.ACC for advice

'I asked friends for advice.'

(10) a. Preposition nach generating the meaning of 'inquire'

Er

saß in dieser spießigen Altbauwohnung rum

he.NOM sat in this

bourgeois old-apartment

around

und fragte nach Dingen, die ihn nicht interessierten.

and asked about things

that him not

interested

'He was sitting in this old bourgeois apartment and asked about things that did not

interest him.'

b. Preposition nach generating the meaning of 'request'

Ohne Genehmigung steckte er sich

without permission

lit

eine seiner Mentholzigaretten an und statt

he himself one of-his menthol-cigarettes on and instead-of

nach dem Aschbecher zu fragen, beschimpfte er die Bürokraten in Brüssel...

for

the ashtray

to ask

abused

he the bureaucrats in Brusells

'Without permission he lit one of his menthol cigarettes, and instead of asking for the

ashtray he abused the bureaucrats in Brussels.'

4.3.2 Prepositions used with spyrja

With the Faroese examples, it is more difficult to spot any clear differences in meaning between the

prepositions eftir and um, since they both seem to able to express a

TOPIC

argument within the

Questioning frame as well as a MESSAGE argument of the Request frame.

The most obvious similarity between Faroese and German um, is that they are both commonly

used together with a word meaning 'advice', ráð in Faroese and Rat in German. In Faroese,

however, the preposition extends over a much wider field semantically, and it is also the most

common preposition used in connection with spyrja. Thus, it may be used to express the request of

something else than advice, as illustrated by (11b) below. It seems, however, also to be possible to

use um within the Questioning frame, where it expresses the

translated as 'about' in English.

29

TOPIC

argument, and would as such be

Table 6: MESSAGE/TOPIC argument of spyrja instantiated with a preposition.

Prep: eftir

Prep: um

Total

Indirect object

2

18

20

Indirect reflexive

0

0

0

No indirect object

6

22

28

Total

8

40

48

(11) a. Preposition um generating the meaning of 'inquire'

Tú

kundi spyrja hann

you.NOM could ask

um

okkurt fjall...

him.ACC about some mountain

'You could ask him about some mountain...'

b. Preposition um generating the meaning of 'request'

...at hann verður

noyddur at fara til bankan

that he.NOM becomes forced

to go

og spyrja um fígging

til eini hús...

to bank.the and ask for financing to a house

'...that he will have to go to the bank and ask for financing for a house...'

For the preposition eftir (which can be said to correspond to German nach), basically the same

semantic scope might be attested as for um. Accordingly, we find example (12a) where the meaning

would most logically be 'ask about' and example (12b) which has the sense of 'ask for'. As was the

case with um, eftir can thus be used both to denote the

well as the MESSAGE argument of the Request frame.

30

TOPIC

argument of the Questioning frame as

(12) a. Preposition eftir generating the meaning of 'inquire'

Eg eri kunnaður um, at

I

am aware

of

landsstýrið

avvarðandi vinnufelag

that concerned

eftir

company. NOM have

hesum máli uttan

government.the.ACC about this

hev-ur spurt

asked

at hava fingið

nakað svar.

issue without to have received any

reply

'I am aware of the fact that the company in question have asked the government about

this issue without having received any reply.'

b. Preposition eftir generating the meaning of 'request'

...tí

ringir onkur

til hansara og spyr eftir Viagra.

thus calls someone.NOM to his

and asks for Viagra

'...thus someone calls him and asks for Viagra.'

4.4 Prepositional constructions expressing the ADDRESSEE

The final point of investigation in this paper is to look at if, and how, the

ADDRESSEE,

which is

normally expressed as an indirect object can instead appear as a kind of adverbial, marked with a

preposition.

Table 7: Addressee arguments expressed through adverbial constructions, percentage of the total

amount of pure active and prepositional clauses in which no indirect object is explicitly expressed.

(The Total column indicates the total number of instances out of which the percentages have been

calculated.)

fragen

spyrja

Tokens

%

Total

Tokens

%

Total

Directional

2

1,0 %

210

0

0%

196

Locational

2

1,0 %

210

1

0,5 %

196

Total

4

1,9 %

210

1

0,5 %

196

31

Putting this in relation to the double accusative construction, the hypothesis might be that an

adverbial construction would be favoured, since it more clearly helps the listener/reader to identify

the ADDRESSEE argument and to distinguish this from the

MESSAGE

argument, than does a construction

where both arguments are marked with the same case.

In Table 7 it is shown how many examples I have found in my material (the pure active and the

prepositional instances) where there is no explicitly expressed indirect object in accusative case, but

where an

ADDRESSEE-like

argument is still expressed, albeit with an adverbial. (The percentages are

out of all pure active and prepositional clauses in which no indirect object is expressed.)

Examples (13a–b) and (14a–b) are the ones that I have found in the German corpus. In total

there are four such examples, and I have chosen to categorize them as either directional or

locational adverbials, depending on the prototypical meaning of the preposition used together with

the ADDRESSEE-like argument.4 In examples (13a–b) the preposition in is used together with an object

in accusative case, which gives it a meaning relatively similar to the English preposition into. In

(14a–b), on the other hand, the preposition bei is used together with an object in dative case. The

meaning of the preposition is here closer to English at.

(13) ADDRESSEE instantiated by a directional adverbial

a. Kennt ihr

einen,

der

jemals vom

know you anyone who ever

Nordpol

zum

Südpol

gelaufen ist?

from.the North-Pole to.the South-Pole walked

fragt Prof. Dr. Dr. Faselfarn (Hannes Hohgräve) ins

is

Publikum. Ja.

asks Prof. Dr. Dr. Faselfarn (Hannes Hohgräve) into.the audience

yes

'Do you know anyone who has ever walked from the North Pole to the South Pole? asks

Prof. Dr. Dr. Faselfarn (Hannes Hohgräve) into the audience. Yes.'

b. "Möchte heute abend

wants

jemand auf eine Party von Moët Chandon? ,

today evening anyone to

fragt Walberer in

a

party of

Moët Chandon

die Redakteurs-Runde. Null Reaktion.

asks Walberer into the editors-circle

zero reaction

'Would anyone like to go to a Moët Chandon party tonight? asks Walberer into the

editor's circle. Zero reaction.'

4 A point may be raised, that these two kinds of adverbials are fundamentally different, since it would logically be

possible to have an indirect object appear in combination with a locational adverbial, whether this is unlikely to be

possible in combination with a directional adverbial. However, I find this categorization useful, since for all

examples of adverbials in my sample, it would be possible to exchange the adverbial for a simple indirect object,

and the adverbial might thus be said to fulfil the role usually played by an indirect object.

32

(14) ADDRESSEE instantiated by a locational adverbial

a. Mehrmals

fragte Iris B. im Oktober vergeblich

several-times asked Iris B. in October in-vain

bei der Sparkasse nach dem Kindergeld

at the Sparkasse for

für ihren Sohn.

the child-benefit for her

son

'In October, Iris B. asked in vain several times at the Sparkasse ('savings bank') for the

child benefit for her son.'

b. Indessen

verrichtet Manager Hoeneß eifrig

Routinearbeit,

meanwhile carries-out manager Hoeneß eagerly routine-work

fragte bei Bayer Leverkusen gar

nach

den Konditionen...

asked at Bayer Leverkusen even about the conditions

'Meanwhile Manager Hoeneß eagerly carries out some routine work, (and) even inquired

at Bayer Leverkusen about the conditions...'