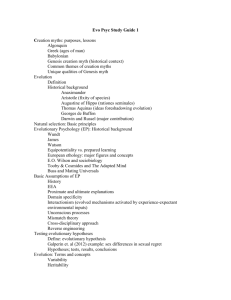

EVOLUTIONARY FOUNDATIONS OF HIERARCHY

advertisement