1 JURISDICTION OF FEDERAL COURTS Federal Crown Proceedings

advertisement

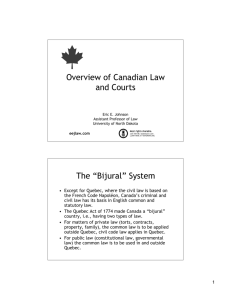

JURISDICTION OF FEDERAL COURTS Federal Crown Proceedings (Remarks by Hon. B. L. Strayer) The Future/Solutions A. Tort (extracontractual civil liability) and Contract Actions by and against the Crown The Problem: “Laws of Canada” 1. Parliament was given power to establish additional courts for the better administration of the “Laws of Canada” (Constitution Act, s. 101). 2. Since Confederation it had been assumed that any common law which Parliament could amend or repeal within its assigned jurisdictions under section 91, etc. was federal common law and part of the “Laws of Canada”. When the Federal Court Act, R.S.C. 1970 c. 10 (2nd Supp) (see now the Federal Courts Act S.C. 2002, c. 8) was originally passed it was assumed the Court could try actions by and against the Crown federal and by or against private parties as long as the subject matter was within federal jurisdiction (see e.g. s. 23 of the Federal Court Act). 3. However, early jurisprudence of the Supreme Court of Canada denied this where the Crown as defendant wanted to counter-claim or bring third-party proceedings, or where a plaintiff wanted to add parties other than the Crown in respect of the same facts (see e.g. Canadian Pacific Limited v. Québec North Shore Paper Co. [1977] 2 S.C.R.1054; R. v. McNamara Construction (Western) Ltd. [1977] 2 S.C.R. 654; foll’d by the Federal Court of Appeal in Pacific Western Airlines v. Canada [1980] 1 F.C 86 and Canadian Saltfish Corp. V. Rasmussen [1986] 2 F.C. 500). For years there were motions to stay in actions in the Federal Court where it was argued that the Crown’s attempted counter-claim or third party claim would 1 involve laws which were not the “laws of Canada”, until in 1990 s. 50.1 was added to the Federal Court Act requiring the Court (on motion of the Attorney-General of Canada) to stay an action where in a claim against the Crown the latter wishes to make a counter-claim or third party claim (see S.C. 1990, c.8, s. 16). 4. Later jurisprudence has in a few cases found that a tort or contract action could be taken in Federal Court by the Crown or against non-Crown defendants, if there is a detailed federal statutory framework governing the parties’ rights. (Rhine v. R.; Prytula v. R. 1980 2 S.C.R.; Petter G. White Ltd. v, Canada 2006 FCA 190; Onuschak v. Canadian Society of Immigration Consultants 2009 FC 1135; Sellathurai v. Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness 2011 FCA 223). This test is often difficult to apply and unpredictable as to result. 5. The net result is to deny many parties access to the Federal Court, even though in a particular case it would be to their advantage to litigate in that Court rather than in a provincial superior court. The writ of the Federal Court runs nation-wide: instant enforcement may be had anywhere in Canada. It can sit anywhere in Canada and has filing facilities in every province. Where a case involves activities or parties in more than one province it can sit where convenient to the parties and readily subpoena witnesses or documents from any part of the country. Members of any provincial bar can appear in it. In class action cases with multi-provincial content or parties, there would be no dispute as to what court should hear the matter, and there would be one set of rules as to who are deemed to be members of the class. Where such actions have been taken concurrently in several provinces the problems have been so numerous that the Canadian Bar Association established a National Task Force to address the problem. It has developed an 18 page Protocol which the Association recommends to all provincial courts for the handling of multi-jurisdiction class actions; additions to the Protocol are still under study. 2 A Legislative Solution 6. As Binnie, J, said in the Telezone case [2010] 3 S.C.R. 588 at para. 18 “This appeal is fundamentally about access to justice. People who claim to be injured by government action should have whatever redress the legal system permits through procedures that minimize unnecessary cost and complexity. The Court’s approach should be practical and pragmatic with that objective in mind”. 7. Parliament should be equally interested in access to justice. In my view the advantages I have suggested to Canadians having the option to litigate in the Federal Court could be made available by a modest legislative amendment. Part of the problem is that the Supreme Court developed the curious doctrine that in ordinary tort (extracontractual civil liability) or contract cases the liability of the federal Crown is governed by federal common law or by provincial law adopted by reference by the Crown Liability and Proceedings Act, R.S.C.1985, c. C-50), but its rights as a plaintiff or counter-claimant or third party claimant is governed by provincial law which cannot be dispensed in the Federal Court. There is ample inconsistency in the jurisprudence that can be demonstrated. But the simple solution would seem to be for Parliament to adopt, by reference, provincial laws wherever they would be relevant to determine a claim by the Crown or against private parties, in the Federal Court, wherever the subject matter of the litigation is within federal jurisdiction. Thus, for example, dozens of plaintiffs, perhaps from many provinces, wishing to claim for family loss through an airplane crash involving alleged negligence of the federal government, private contactors spread over several provinces, and the airplane manufacturer, could do so in the Federal Court which might be their preferred choice. Claimants in respect of another kind of transportation, by water, have been able to join all such parties as defendants in the Exchequer Court or the Federal Court for over 100 years. 3 8. There is ample precedent for such incorporation by Parliament of provincial law by reference: see e.g. section 3 of the Crown Liability and Proceedings Act, which provides that the Crown is liable for such damages for which “if it were a person” in the relevant province it would be liable for acts of a servant or a duty attached to the ownership of property: or section 39 of the Federal Courts Act which adopts by reference provincial limitation statutes in any proceeding arising in that province. 9. The Federal Courts regularly have to apply provincial law incidentally in determining income tax, admiralty, intellectual property, expropriation and many other cases. They must apply it in actions against the Crown and should be able to apply it in actions or claims by the Crown or against parties other than the Crown. B. Concurrency regarding administrative law issues in the Federal Courts and Provincial Superior Courts 1. The grant of exclusive jurisdiction in the Federal Court over remedies against federal agencies in s. 18 of the Federal Courts Act lists in paragraph (a) those remedies as certiorari, prohibition, mandamus, quo warranto, declaratory relief, and in paragraph (b) relief “in the nature of relief contemplated by paragraph (a)”. Applications for such relief are to be made within 30 days of the decision to be attacked, unless the Court extends the time (s-s. 18.1(2)). 2. For reasons which have been discussed here today in relation to the Telezone decision this wide grant of exclusive power over judicial review exercised through these remedies in respect of officers and institutions of the federal government was designed to make such judicial review more accessible, timely, and its exercise by a specialised single court more uniform and consistent. That exclusivity has been eroded over the years. 4 Declarations in Provincial Superior Courts 3. The Supreme Court in Attorney-General of Canada v. Law Society of British Columbia [1982] 2 S.C.R. 307 held that notwithstanding s. 18 a provincial superior court had jurisdiction to issue a declaration that a federal agency did not have the authority to take steps against a provincial law society because the governing federal statute did not by its terms authorize such steps. While not necessary to so decide in that case, it also said that a declaration could equally be made if the agency acted without constitutional authority. Since then many such declarations have been made by provincial courts. The Supreme Court has, however, held that if an application for a declaration that federal authorities are acting contrary to the constitution is made in a provincial superior court the judge has a discretion to stay the application on the grounds that there is an effective and appropriate forum available to the applicant in the Federal Court (Reza v. Canada [1994] 2 S.C.R. 394). This case concerned immigration and there appears to be a recognition that the Federal Court has more expertise and experience in immigration law. The principles for exercise of this discretion were drawn from habeas corpus cases. Habeas corpus in Provincial Courts 4. In such cases it has been held that while a federal decision placing a person in custody or in more strict custody may be attacked by certiorari in the Federal Court it can also be attacked in a provincial superior court by an application for habeas corpus, possibly with certiorari in aid to quash the custody decision (May v. Ferndale Institution [2005] 3 S.C.R. 809). In this case the applicants, federal prisoners, had been transferred from minimum - to medium-security facilities. They sought habeas corpus in the British Columbia Supreme Court. When the matter finally reached the Supreme Court of Canada the latter confirmed that there were concurrent powers of judicial review over such decisions and where a habeas corpus application is made to a 5 provincial court it should hear the matter unless (1) there is a right of appeal from the decision which has not been pursued or (2) there are factors which make the Federal Court remedy more accessible, more expert, or advantageous to the applicant. Exception (1) did not apply here, and the factors described in (2), in the view of the Court, made the provincial court route the more advantageous. It was said that a remedy can be obtained more rapidly in the provincial court, that it is more locally accessible, and the burden of proof is more onerous in a certiorari proceeding than in a habeas corpus proceeding where, once custody is established, the custodian must justify it. Further it was said that “the greater expertise of the Federal Court in correctional matters is not conclusively established”. Damage actions in provincial courts 5. We have today heard of the issues arising out of Telezone [2010] 3 S.C.R. 585 and its five companion cases decided by the Supreme Court of Canada last year. In each case a plaintiff had commenced an action for damages, claiming loss as the result of some decision taken by a federal agency or official. Several of these actions were commenced in a provincial superior court such as the Superior Court of Ontario in the Telezone case, others in the Federal Court. In none of these was the validity of the order directly attacked. In all of these cases the Supreme Court held that such damage actions did not amount to a collateral attack on the federal order: but in some cases it was recognised that if the Crown raised the defence that it acted under statutory authority the trial court could consider whether the validity of the original order was relevant and if so decide whether it was valid for the purposes of the action. It was emphasised that judicial review is a public law remedy for the purpose of maintaining the rule of law, while recovery of damages flowing from that order is a private law remedy whose purpose is compensation. In today’s discussion the problems flowing from provincial courts entertaining 6 such actions when there has been no adjudication by the Federal Court have been described. 6. Realistically it must be accepted that the Telezone approach is now the firmly established view of the Supreme Court and therefore of the courts generally for an indefinite time. Nor can it be expected that Parliament will rush to preserve the exclusivity of powers of the Federal Court to adjudge the validity of federal decisions. But I do think there are some positive elements in the jurisprudence. Not a Direct Diminution of Federal Court Power 7. Unlike many other decisions, Telezone does not deny the jurisdiction of the Federal Court: it only provides possible concurrent capabilities for provincial superior courts to consider tangentially the validity of federal decision-makers. In many such cases the Federal Court would never be called upon for judicial review, because of the passage of time or the expiration of the order in question. A more functional jurisprudence? 8. Binnie J., the author of the Telezone doctrine, assures us (para. 18, quoted supra) that the case is “about access to justice”, and that claimants should have access to redress “through procedures that minimize unnecessary cost and complexity . . . . the Court’s approach should be practical and pragmatic with that objective in mind . . . .” In Canada v. McArthur [2010] 3S.C.R.626 at para. 12 he advocates a “textual, contextual and purposive interpretation of the Federal Courts Act” in these matters. In Telezone (para. 78) he also said that provincial superior courts have a discretion to stay a damages action if it finds that the essential character of the proceeding is a claim for judicial review. I question that the exercise of discretion by provincial courts on these various grounds will always result in them hearing the case. The Federal Court’s depth of experience in certain areas may militate in its favour as was recognised in the Reza case 7 in matters of immigration and seemingly in R. v. Ahmad 2011 SCC 6. in matters of national security, but perhaps not in matters of corrections (May v. Ferndale Institution, supra). 9. Binnie J. in Telezone (para. 23) said that he did not interpret the Federal Courts Act to ‘‘require an awkward and duplicative two-court procedure with respect to all damages claims that directly or indirectly challenge the validity or lawfulness of federal decisions’’. I respectfully agree. In fact, that Act actually allows all such matters to be dealt with in one proceeding in one court: namely, the Federal Court. An application for judicial review can be converted into an action (Federal Courts Act s.-s. 18.4 (2)) and there may be added to it claims for recovery of money or compensation (Shubenacadie Indian Band v. Canada 2002 FCA 255 para. 4; Hinton v. Canada 2008 FCA 215, para. 45). Lawyers should govern themselves accordingly in not choosing a forum, a provincial superior court, where it is possible that an objection of collateral attack may be raised by the Crown. 10. Much of the issue underlying Telezone is the rationale, often repeated by the Supreme Court, that an action for damages flowing from a governmental decision is not an attack on the validity of that decision: the issue of validity would arise only if the Crown argues a defence of statutory authority. (See, e.g.Telezone paras. 47, 69-72; Canadian Food Inspection Agency v. Professional Institute of the Public Service [2010] 3 S.C.R. 657). It has emerged in past jurisprudence that where harm, otherwise tortious, is caused by action of a government pursuant to a government decision, it is not actionable if the decision is one of policy, but may be actionable if the decision is as to the manner of implementation of that policy. (See e.g. Just v. British Columbia [1989] 2 S.C.R.2 re: common law provinces; Canadian Food Inspection Agency v.Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada supra at para. 27, re: Quebec). In the case of a 8 policy decision a provincial court would find itself having to address the validity of the policy decision in terms of the powers of the decision-maker and it therefore cannot be said with assurance that because the statement of claim doesn’t attack the validity of the decision the provincial court will not have to consider that question. In the case of the manner of implementation I am satisfied that a perfectly valid decision may still give rise to tortious liability because of the manner of its announcement or implementation, but that has not been universally recognised. It is less clear how this body of law applies where the Crown is being sued in contract and pleads that its alleged breach of contract was authorized by statute or regulation. Conclusions 11. We see then that there are many points of discretion open to provincial courts in deciding whether to entertain proceedings that incidentally may require them to review the validity of federal decisions. The jurisprudence suggests that important factors to be considered are access to justice for the claimant or applicant (including elements of location, speed, and expense), relative expertise, and efficient procedure. The Federal Court for its part should strive to ensure that it be seen as offering these advantages. 9