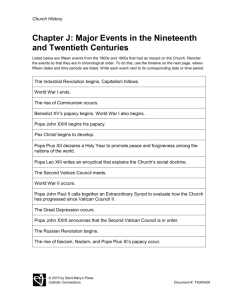

chapter x - International College of the Bible

advertisement