the draft.

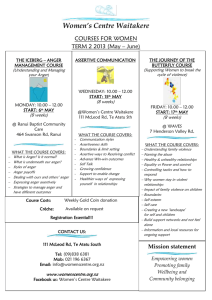

advertisement