The Lily Pool, the Mirrors, and the Outsiders: Envisioning Home and

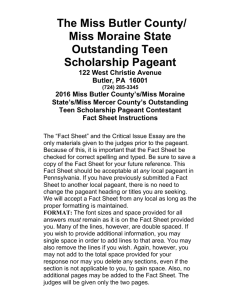

advertisement

Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies 38.1 March 2012: 249-275 The Lily Pool, the Mirrors, and the Outsiders: Envisioning Home and England in Virginia Woolf’s Between the Acts Ching-fang Tseng Department of English National Taiwan Normal University, Taiwan Abstract Written against the historical context of the threats of fascism and World War II, Between the Acts’s portrayal of rural England that highlights its traditional way of life, the everlasting rural landscape, and the pageant then in vogue seemingly echoes the prevailing national imagination during the war-crisis years. Rather than replicating the nostalgic ruralist vision of England on the verge of war, the novel not only furthers Woolf’s critique of the dictators in England in Three Guineas, but also enacts the essay’s visionary idea of the “Outsiders’ Society” in the setting of the English country. A prominent figure in Between the Acts is the cultivated observer in rural England, who is there to apprehend landscape as well as the universal evolutionary order. Encapsulating the ocularized social power of the ruling landowning class, he embodies Englishness and “civilization” as the apex of the developmental progress of humankind. Woolf responds to such Englishness by positing episodes in the novel involving La Trobe’s village pageant. The pageant invokes an “Outsiders’ Society” composed of heterogeneous, anonymous private spectators in resistance to the hegemonic perception of the gentry-audience, thus making the latter think home landscape, “Ourselves,” and civilization in a different light. At the same time, the “Outsiders’ Society” is also enacted through Between the Acts’s multi-layered, open-ended, and self-reflexive form, which disallows closure and totality of meaning and predominance of the authorial vision. Keywords Between the Acts, Three Guineas, rural England, landscape, the cultivated observer, Englishness, the “Outsiders’ Society,” the Outsider-artist I express my sincere gratitude to the anonymous readers of an earlier version of the essay, whose constructive comments help me improve the argument and organization of the essay. 250 Concentric 38.1 March 2012 Published posthumously in 1941, Virginia Woolf’s last novel Between the Acts is noted for its thematization of England and Englishness, and its hybrid, interrupted form that contains the playwright La Trobe’s village pageant and the cacophonic, fragmentary voices its performance effects. Written against the historical context of the threats of fascism and World War II, the novel’s portrayal of rural England highlighting its traditional way of life, the everlasting rural landscape, and the pageant then in vogue seemingly echoes the prevailing national imagination during the war-crisis years, which nostalgically yearns for the placid, eternal home as embodied by the idyllic English countryside. In correlating social community with the audience of the pageant or art, the novel’s exploration of how to ensure the survival of community as the nation faces the threat of obliteration continues and complicates Woolf’s historical reflection on war and dictatorship in Three Guineas. As Patricia Klindiens Joplin points out, Woolf in Between the Acts “seizes hold of the gap, the distance, the interval, and the interrupted structure not as a terrible defeat of the will to continuity or aesthetic unity [but] . . . elevates [them] to a positive formal and metaphysical principle” (89). Likewise, Pamela Caughie argues that the novel “gives [contingencies and interruptions] preference, and those numerous breaks many critics see as a sign of discontinuity and a faulting of structure actually enable the acts [of art] to be continually renewed” (53). While some critics pay attention to Between the Acts’s unconventional presentation of the form and audience of art and the artist’s role that diverge sharply from Woolf’s previous visions of such, still others focus on Between the Acts’s anti-fascist meditation on the communal mode as experimentally pluralistic or alternatively unified by creative art. While Brenda Silver suggests that the pageant in the novel recreates the Elizabethan playhouse and “provide[s] a form of community that will survive the coming war” (296), Michele Pridmore-Brown maintains that the community that takes form among the audience of La Trobe’s pageant “emphasizes the particularities of the auditor or receiver” and by means of the “noise of gramophone” “subverts the political message propelling civilization into World War II” (416, 419). Similarly, Christine Froula asserts that “the pageant’s freedom from fixed, ascertainable meaning” gives rise to a community of diverse, discordant free spectators “against the totalitarian threat across the Channel” (322, 320). Yet despite that the novel’s radically experimental vision of community represents the Outsider-artist’s independence and creativity in defiance of dictatorial control as has been discussed in Three Guineas, Between the Acts presents a portrayal of communal life that is culturally and socially specific as it ponders the ideas of England and Englishness in a precarious, ominous moment when the nation faces Ching-fang Tseng 251 war. As Alex Zwerdling writes, the novel displays an “acute longing for an earlier, more civilized phase of English culture” while harboring an apocalyptic view of the community’s degeneration and decay as “a prehistory of the present” (308, 317). Jed Esty perceives the novel’s nostalgic “nativist turn,” its interest in traditional, pastoral English culture, as being used as “a bulwark against . . . continental fascism and British imperialism” (93, 96). Gillian Beer also argues that the community depicted in Between the Acts “typifies the attitudes that have brought the country to the brink of war and of fascism,” and that significantly the novel “sought to produce another idea of England” (129-30, 147). Around the time of completing Three Guineas, Woolf had already outlined a tentative scheme for her next novel in her journal on April 26, 1938: . . . why not Poyntzet Hall: a centre: all lit. discussed in connection with real little incongruous living humor; & anything that comes into my head; but ‘I’ rejected: ‘We’ substituted: to whom at the end there shall be an invocation? ‘We’ . . . composed of many different things . . . we all life, all art, all waifs & strays—a rambling capricious but somehow unified whole—the present state of my mind? And English country; & a scenic old house—& a terrace where nursemaids walk? & people passing—& a perpetual variety & change from intensity to prose & facts. (135) The passage clearly reveals, after denouncing dictators and militarism and deliberately adopting the Outsider role with the resolve to have no allegiance to country in Three Guineas, that Woolf’s new novel will feature the traditional life and culture in rural England which represent a mythologized notion of Englishness. And yet the seeming discontinuity or contradistinction of Three Guineas and Between the Acts is actually illusory. For just as she decides to have “‘I’ rejected” and “‘We’ substituted” envisioning a “unified whole” that is nonetheless “rambling capricious,” the novel furthers her critique of dictatorship not only on the continent but also in England, and moreover enacts the essay’s visionary idea of the “Outsiders’ Society” in the setting of the English country as it meditates on communal constitution and survival, as well as the renewal of notions of Englishness and civilization. Rather than finding solace or escape in the nostalgic ruralist vision of England on the verge of war, Between the Acts exposes the hereditary and masculinist class power embodied by the dictatorial, privileged “I” in the traditional rural locality, who represents too the universalist “perfect type” of 252 Concentric 38.1 March 2012 “Man” delineated in Three Guineas. Governing rural England and also the masculine public world, the elite ruler exemplifies what Woolf in her October 26, 1940 journal entry describes as “the complete Insider” who personifies the “glory of the nineteenth century” and does “a service like Roman roads” (Diary 333). He is the eminent public man who has made the mainstay of the society; he has the honor to chronicle the history of the imperial nation whose master narrative nonetheless is indifferent to “the forests & the will o the wisps” (Diary 333). Epitomic of “the complete Insider,” the gentleman squire in Between the Acts manifestly acts the role of the hegemonic cultivated observer. As his cultivated gaze apprehends landscape as well as the universal evolutionary order, he not only encapsulates the ocularized social power of the ruling landowning class in rural England, but also embodies simultaneously Englishness and civilization signifying the apex of the developmental progress of humankind. Yet in place of the stratified social order paternalistically ruled by the cultivated observer and naturalistically mirrored by the rural landscape, Woolf envisions in Between the Acts an unbounded, dynamic, and yet unified “We.” The Outsider-artist’s creative, experimental vision of community does not merely defy and challenge the thriving fascism on the continent. It determinedly and profoundly contests the aestheticized social order rooted in England while endeavoring to transcend both social and national boundaries. Making the gentry-audience perceive home landscape, “Ourselves,” and civilization in an alternative way, La Trobe’s village pageant triggers the “Outsiders’ Society” composed of heterogeneous, anonymous private spectators in resistance to the hegemonic cultivated perception. And as the Outsider-artist’s art is meant to facilitate and nourish community based on unconstrained, creative private visions, the “Outsiders’ Society” is at the same time enacted as well through Between the Acts’s multi-layered, open-ended, and self-reflexive form, which disallows closure and totality of meaning and predominance of the authorial vision. “The Green Mirror” and the Lily Pool: The Cultivated Observer at Pointz Hall Depicting life in the English countryside, Between the Acts mainly recounts the festive annual village pageant for which the local gentry gather on a June day in 1939. Its portrayal of the domestic and communal lives in the country centers on the Olivers’ country house, Pointz Hall, where the continuity of tradition and the idyllic life and rural landscape seem to withstand the flux of time. The setting and subject of Between the Acts evidently resonate with the prevalent imagining of England in Ching-fang Tseng 253 Woolf’s society, which regards countryside England, the South Country that projects “an organic and natural society of ranks” (Howkins 80) or the so-called “Constable country of the mind” (Potts 160), as embodiment of the everlasting Home signifying order, health, stability as opposed to the ephemerality, decadence, and unnaturalness of urban modernity. Nevertheless, the stable, stratified social order depicted in Between the Acts, whose narrative progression pivots on the activities at Pointz Hall, also reflects the rootedness of the contemporary national imagination in the rural tradition that dates far back to the Middle Ages. Raymond Williams has observed: “English attitudes to the country, and to idea of rural life, persisted with extraordinary power” in the modern times (2). And the persistent “forms of the older ideas and experiences” associated with rural life in the English country attest to the resilience of the aristocracy after the ascendancy of the middle classes (2). Furthermore, with its uninterrupted tradition and habits, the way of life in rural England as constituted by the “idealized ‘organic’” class and gender hierarchies is characterized by a “solidarity of place” which postulates the hierarchized “natural order” of the manor house and the village, of the domestic household and the public life in the pastoral country (Davidoff 44, 46). And as Leonore Davidoff points out, life in rural England that seemingly reflects natural harmony and endurance relies on a deliberate “blurring” of “the aesthetic” and “the social,” as the naturalized domestic and communal lives and also the rural landscape appear not only altogether integrated but also “aesthetically pleasing” (45). In Between the Acts, the continuity of the traditional social order and habits in the country manifestly echoes the timeless rural landscape owned and appreciated by the gentry. The local genteel families have lived in the secluded countryside for many a generation: in the present time, they still seem able to reply to the “roll call” of Mr. Figgis, author of the 1833 Guide Book—“Adsum; I’m here, in place of my grandfather or great-grandfather” (52, 75). The family names of the villagers, on the other hand, can be found in “Domesday Book,” the census made by William the Conqueror in 1086, which is an earlier date of descent than the gentry’s in the rural locality (31).1 The changeless, uninterrupted way of life in the country corresponds with the enduring natural scenery, which seems to mirror the organic social harmony. The view the gentry enjoy has always remained the same: as Mr. Figgis observed, Pointz Hall “commanded a fine view of the surrounding country. . . . The spire of Bolney Minster, Rough Norton woods, and on an eminence rather to the left, Hogben’s Folly”; what he said “still told the truth” as “1830 was true in 1939” (52). 1 For more discussion on this, see Johnston 260. 254 Concentric 38.1 March 2012 Under “the shelter of the old wall” in the garden, the Oliver family and the guests taking their after-lunch coffee share not only the shade but also the view: “They looked at the view; they looked at what they knew, to see if what they knew might perhaps be different today. Most days it was the same” (52, 53). Like the annual village pageant which repeats every year the same preparatory procedure as if always the “same chime followed the same chime,” the enduring view of landscape the gentry look at bespeaks the naturalness of the social order, under which the ruling landowning class plays the role of the leisured audience appreciating culture and natural beauty (22). As Bart Oliver blithely states, “Our part . . . is to be the audience,” “a very important part too,” or as his son Giles sulkily grumbles, “‘We remain seated’—‘We are the audience,’” the gentry as the privileged ruling class in the country has been the leisured viewers rather than the serving or toiling laborers (58, 59). The pervading imagery of chairs in Between the Acts underscores leisure as the distinctive prerogative of the gentry: there are the assortment of chairs prepared for the gentry-audience on the terrace (75), the “Windsor chairs” of Lucy Swithin and Bart Oliver in the barn (108), and the “monumental” chair in which the old squire dozes off after dark (218). Though on the June day the village pageant is the reason why the local gentry gather together, it is their unfailing, spontaneous congruous appreciation of the view that unequivocally indicates their class distinction as the landowning class. The pursuit of “natural beauty” or “pleasing prospects” in the English country first emerged in the eighteenth century, when the continual process of land enclosing which had begun hundreds of years before intensified (Williams 122). The enclosure made by the English landlords at the expense of large extents of villages and farmlands, as Williams puts it, is nothing less than acts of “imposition and theft” (122). With the historic accelerated enclosure and attendant brutal changes to the land and rural way of life, a newly “discovered” countryside is taking shape as a “cultural and aesthetic object,” rather than merely site of agricultural production (Bermingham 9). As Ann Bermingham asserts, “Precisely when the countryside . . . was becoming unrecognizable, . . . it was offered as the image of the homely, the stable, the historical” (9). The landlords then begin to build landscape parks and prospect views which emphasize in particular the notions of “nature” and “the natural,” making the landscape they hold and create look as if emptied of artificial boundaries and signs of labor or communication (10). Architecturally arranged to look merged with the surrounding landscape, the country house indicative of land ownership, together with the landlord’s Ching-fang Tseng 255 aggrandized property and agricultural production, thus seem to become part of the timeless natural scenery and the processes of nature. At the same time, the viewing or appreciating of the aestheticized landscape that embodies naturalness and eternal beauty is self-consciously taken up by the landlords, who endeavor to agriculturally as well as aesthetically improve the country estate, as “an experience in itself,” a routine, pleasurable practice of art that indicates taste and social status (Williams 121). From an elevated position, such as on the “terrace” and “lawns” which seamlessly conjoin the country house and the receding surrounding landscape, or from the country house’s “large windows” overlooking the estate’s expanded layout, the landlord observes the landscape he owns (Williams 124). The aesthetic appreciation of landscape is performed by a single person from specific angles, following a proper set of perceptual rules and framing structures which correspond with the compositions and light gradations in painting. The observer knows the proper procedure of “jockeying for position, of screwing up the eyes, of moving back and forth, of rearranging objects in the imagination” (Barrell, The Idea of Landscape 5). As Williams succinctly remarks, “It is in the act of observing that this landscape forms” (126). Such observation of landscape thus has as much to do with its physical contours as with applying abstract principles of beauty, which analogously can be applied to paintings and literature on landscape. Mastering the aesthetic appreciation of landscape requires the cultivation of correct taste, and its “genuinely abstract aesthetic,” ultimately “a poetic or pictorial convention,” entails separation and control, characteristics of the privileged observing position occupied by the leisured, educated ruling class (Williams 126). The cultivated or aesthetic perception of landscape therefore betokens not only the landowning class’s economic and political dominance but also its cultural hegemony. In Between the Acts, the social power of the ruling landowning class is distinctly ocularized, as the gentry’s distinctive practice of looking at the view suggests not just their ossified, insular class purview and class self-identity, but the fixity of the hierarchized class division in the English country. The novel describes in a vivid, detailed fashion the topography of the Olivers’ country estate, which represents the extent and composition of the landscape view the gentry collectively share. Significantly, located at the steep end of the “stretch of turf half a mile in length and level,” which is an integral part of the view the Oliver family command, the lily pool literally delimits the gentry’s social space and scope of vision, and also symbolizes their self-interested, narcissistic class identification (10). Within the gentry’s perceptual bounds emblematized by the reflecting surface of the lily pool, the pleasant view of the country landscape bespeaking the everlasting peace and 256 Concentric 38.1 March 2012 harmony of home and the social order is all the gentry habitually “see.” Beyond the lily pool, though, is still the nether, scarcely trodden space outside the gentry’s purview: “Beyond the lily pool the ground sank again, and in that dip of the ground, bushes and brambles had mobbed themselves together. It was always shady; sun-flecked in summer, dark and damp in winter” (56). However self-evident it appears, reflection on the lily pool hinges on suppression of the irregular, incomprehensible views occluded by and alien to the changelessly illumined surface. Just as the villagers are “[s]wathed in conventions” and “couldn’t see” there might be alternative ways of living and doing things, the gentry-audience who “respected the conventions” avoids walking beyond the lily pool to step on the sunken ground reserved for the villager-actors, or for the children catching butterflies in the summer (64, 151). When looking at the view that embodies the eternal home and essentialized, mythologized Englishness, the gentry also perceive their collective bond and class self-identity that are repeatedly authenticated and assured. This explains why the recently-built houses seen to impair the beauty of the view that conjures up the gentry’s gratifying familiar sense of self should aggravate them and provoke their criticism. Looking for seats before the pageant starts, some members of the gentry-audience express their disapproval of the obtrusive sights impinging upon the view: “That hideous new house at Pyes Corner! What an eyesore! And those bungalows!—have you seen’em?” (75). As a tangible, visible symbolization of their social status, the view of landscape evoking the gentry’s sense of belonging makes them unwittingly assume “some . . . determinate relation to its givenness as sight and site” and associate their class self-identity with the natural scenery (Mitchell 2). Back in 1918, Woolf in her review essay “The Green Mirror” already paid attention to the “family theme” in early twentieth-century British novels that highlights the perpetuated class self-identity and prosperity of the hereditarily propertied family (215). Commenting on the namesake in Hugh Walpole’s novel The Green Mirror, which has always hung in the drawing room of the Trenchard family, Woolf writes: “Many of generations of the Trenchard family had seen themselves reflected in its depths. Save for themselves and for the reflection of themselves they had never seen anything else for perhaps three hundred years, and in the year 1902 they were still reflected with perfect lucidity” (214). The treasured “green mirror” betokens the fixed and complacent inherited self-image of the Trenchard family, which remains lustrously distinct even in the modern era. The enduring self-image reflected by “the green mirror” also bespeaks the family’s unbroken material advantage: “If there was any room behind the figures for chair or table, tree or field, Ching-fang Tseng 257 chairs, tables, trees and fields were now and always had been the property of the Trenchard family” (214-15). Furthermore, signifying not only the self-image of one Trenchard family but also that of the entire ruling class, “the green mirror” represents as well “a type of the pig-headed British race with its roots in the past and its head turned backwards” (215). While betokening inherited familial prestige and fortune, the indestructible patrimonial mirror symbolizes the uninterrupted narcissistic self-identification of the ruling class and also the nation which is accompanied by an insular and backward-looking inclination. Signaling the prerogative of the landed genteel families, the view of landscape in Between the Acts patently serves a function similar to the imperishable hereditary “green mirror,” through which the gratifying, abiding self-image epitomic of class supremacy and Englishness is repeatedly imagined and affirmed. As it emblematizes the landed gentry’s class dominance and self-identity, the lily pool synecdochic of the view essentially signifies the masculinist preeminence of the universalist cultivated perception mastered by the gentleman squire. Between the Acts notably opens with Bart Oliver’s talk in the big room with Mrs. Haines, the gentleman farmer’s wife, about the cesspool and the panoramic view of territorialized national history. As symbolized by the big room’s windows which appear at the beginning and the end of the novel, what the old patriarch perceives represents the hegemonic view epitomic of Englishness and civilization that dominates the rural locality as well as the national public. And if the windows of the big room symbolize the masculinist hegemonic vision, the books housed in the country gentleman’s library more concretely and eloquently embody its lasting and transcendent significance. Pointz Hall is located at “the very heart of England,” and its library—“the heart of the house”—stores collections of books that are likened to “the mirrors of the soul” (16). Though at the present moment people must acknowledge “the mirror that reflected the soul sublime, reflected also the soul bored,” standing “[w]ith his arms akimbo” “in front of his country gentleman’s library,” Bart Oliver still ponders the bequeathed, enlightening truth that books are “the treasured life-blood of immortal spirits” and poets “the legislators of mankind” (16, 115). However, the transcendence of the soul-reflecting books he is contemplating is belied by their exclusive ownership, as such substantial collections of books can only be found in the country gentleman’s library which is solely occupied by Bart Oliver the cultivated observer. Indicative of learning and refinement, landscape art is associated with “political authority” whose measure is based on the discourse of “civic humanism” (Barrell, “The Public Prospect” 19). As John Barrell points out, the cultivated observer of landscape possesses the “true 258 Concentric 38.1 March 2012 taste,” as being able to “abstract” the “generic classes” of objects in nature rather than seeing only the “accidental forms” of them (“The Public Prospect” 24, 25). Unfettered by the minute, random sights of objects and by “the tyranny of sense or need,” he perceives panoramically the organizing structures and arrangements of the prospect view (26). Superior to those imprisoned “within their few acres at the bottom of the eminence,” the cultivated observer is “liberal,” “learned,” and “polite” as contrasted with the “ignorant,” “servile,” and “vulgar” who cannot generalize and abstract particular objects submerged in contingency (27). While those within the landscape are “the observed” and hence “the ruled,” “the observers” above the landscape get to perform the role of “the rulers” who apprehend it (33). And with reason and the “liberal mind,” the cultivated ruler-observer has not merely the capability to abstract but the “will” to transcend instincts and private interests (29, 27). He is then qualified to be the “public man,” the “free citizen” participating in public affairs; masterfully perceiving the landscape views as well as the “order of society” and “nature,” he “abstract[s] the true interests of humanity, the public interest” (29, 27). While the aesthetic perception of landscape manifestly signals class hegemony, the gentleman squire as the elite ruler-observer exemplifies at once class cultivation and the free and liberal mind of the public man concerned with universal truth and the good of the public and humanity. Though the taste for landscape materially rests on class opulence, the underlying logic of the prospect view presupposes the autonomous, universal public subject. The elite ruler-observer typifies what Martin Jay describes as “Cartesian perspectivalism,” “the modern scopic regime per se,” which combines the Renaissance invention of perspective in the visual arts with scientific rationality of the Cartesian subject emergent in the seventeenth century (4). Yet even though the cultivated surveying of landscape, as Barrell notes, results in a definite set of “visual and linguistic procedures” that ultimately renders every landscape observed “part of the universal landscape,” the prospect view signifying transcendence and civic governance is actually only commanded by gentlemen from the landowning classes and the newly flourishing mercantile middle classes (The Idea of Landscape 7). This select group of men constitutes the ruling power ever since the eighteenth century, whose consolidation remarkably signals an “ideological rapprochement” between the aristocratic and middle-class elites (Eagleton 32). As Terry Eagleton remarks, the “ruling social bloc” composed of cultivated gentlemen engenders “a ‘public sphere’—a political formation rooted in civil society itself,” the operation of which pivots on the free and enlightened universal subject, and also on the code of refined manners derived from patrician Ching-fang Tseng 259 gentility (32). If the bourgeois public sphere functions through the internalized power of the autonomous, equal universal subject, then the social constitution of the ruling body is distinctly delimited by gentlemanly manners and taste considered not merely proper but spontaneously styled. Such “aesthetics of social conduct or ‘culture,’” contends Eagleton, serve as a “vital mediation from property to propriety,” cloaking the grim “structures of power” founded on possessions of lands and wealth in the appealing garment of “structures of feeling” (42). The taste that in principle represents universal truth and disinterestedness in reality develops into the “aesthetics” of cultivated refinement that signal and help consolidate the hegemony of the ruling political and social powers. Originally the prerogative of the landed squire, the prospect view of landscape gradually also becomes a vital pursuit of the entrepreneurial middle-class man, who, as termed by Elizabeth K. Helsinger, is the “vicarious investor of the British scenery,” educating himself diligently about the rules and procedures of the correct taste (25). As such, the aesthetic perception of landscape eventually represents “a national topography” signifying culture and Englishness, over which hereditary and self-made gentlemen alike imaginarily share “a national consciousness” (24). The gentleman squire in Between the Acts thus not just carries on ancestral lineage and patrimony in the English country, but embodies the masculinist preeminence of the elite ruler-observer governing the rural locality and the nation. Epitomizing at once Englishness and the cultivated taste, he lays claims to civilization and disinterestedness ensured by an ostensibly universal public which operates and legitimates itself by enlightened communication and knowledge as indicated by the newspaper and the establishments of learning. As the owner of Pointz Hall, Bart Oliver is obliged to “tell them [the guests] the story of the pictures”; just like the ancestor “holding his horse by the rein” in the picture who “had a name” and “was a talk producer,” the patriarch continues and disseminates the verbally as well as pictorially chronicled patrilineage of the Oliver family (48, 36). On the other hand, Bart Oliver also acts as the detached, disembodied ruler-observer exemplifying “Cartesian perspectivalism” who apprehends from a height the abstracted universal order of beauty, nature, and civil society. The old squire as the public man exercises superb discernment of art and landscape views, and staunchly believes in reason, disinterestedness, and rationalistic universal truths. As the inheritor as well as transmitter of culture and knowledge, he “would carry the torch of reason till it went out in the darkness of the cave” (206-07). While constantly mocking the superstition of the servants and her sister Lucy, he himself trusts the Encyclopaedia and the meteorologist’s weather forecast and 260 Concentric 38.1 March 2012 authoritatively claims that Pointz Hall’s distance from the sea is “[t]hirty-five [miles] only,” “as if he had whipped a tape measure from his pocket and measured it exactly” (22, 29). Just as he decides that the horse’s “hindquarters” in the ancestor’s picture “were not satisfactory,” he magisterially leads everyone in the garden to appreciate how the view instantiates the landscape taste axiomatically applicable to the immortal works of the great painters: “‘There!’ Bartholomew exclaimed, cocking his forefinger aloft. ‘That proves it! What springs touched, what secret drawer displays its treasures, if I say’—he raised more fingers—‘Reynolds! Constable! Crome!’” (49, 54-55). As an enlightening doyen of the public world, Bart Oliver, who links “the lamplit paper” with “reason,” also “flicked on the reading lamp” for the family, the “circle of the readers, attached to white papers” (204, 216). The old squire’s “torch of reason” that symbolizes the universal public interests enables the family’s vicarious participation in what Benedict Anderson calls the imagined community of the nation, whose imaginarily conceived “fraternity” or “deep, horizontal comradeship” which is “secular, historically clocked” pivotally relies on people’s daily “mass ceremony” of reading the newspaper (Anderson 7, 34). And as the public man with the transcendent “liberal mind,” Bart Oliver grumbles about his people’s parochial concern as typified by the usual fund-raising at the end of the pageant—“Nothing’s done for nothing in England”—but values the disinterested magnanimity of the man “connected with some Institute” who “goes about giving advice, gratis” on art (Woolf, Between the Acts 177, 49). Long playing the eminent role of “the complete Insider” ruling the public world, the gentleman squire personifies not just class cultivation and dominance, but also the universalist, masculinist command and conception of taste and civilization. Further, the gentleman squire as the cultivated ruler-observer has not merely landscape as his observed object, but the uncivilized, alien others perceived as antithetical or inferior to the values of Englishness and civilization. His commanding universalist gaze essentially accommodates the exotic species and peoples across the globe under the Eurocentric historical or evolutionary framework. In parallel with the recurrent images of savages and the prehistoric in Between the Acts, the Outline of History that records the times of “the iguanodon, the mammoth, and the mastodon; from whom presumably . . . we descend” and features pictures of prehistoric beasts constantly preoccupies Lucy Swithin, who faithfully, unwittingly mimics the perception of her retired colonial-administrator brother (8-9). Just like Bart Oliver’s talks and reading of newspapers, the Outline of History as avidly read and imagined by Lucy marks too the beginning and end of the day at Pointz Hall. Ching-fang Tseng 261 As Edward Said observes, in the era of rapid, competitive imperial expansion, the British hegemony fundamentally hinges on a self-identity imagined against the background of a “geographically conceived world,” or a “hierarchy of spaces” under which “home,” center of the geographical imagination, exercises dominant military, economic, and cultural influences (52, 59). This “geographical” sense of the Western self underlies the “authority of the European observer” that appears extensively in novels, travel tales, scholarly treatises, and business accounts (58). The vision of “the European observer” significantly corresponds with the scientific narratives of the species and races in the world in various disciplines (59). As Mary Louise Pratt argues, linked with “the European male subject of European landscape discourse,” the “seeing-man” figure in natural history vitally encapsulates the European “planetary consciousness” that authorizes imperialist dominance and subjectivity in the innocent guise of epistemological neutrality (7). And the empiricist, rationalist observer in disciplines like natural history and anthropology employs evolutionary time to construct a universal teleological paradigm of history and development that encompasses all peoples and species in the world. According to Johannes Fabian, the universal historical development perceived by the scientific gaze in these disciplines is consistently “visualized” and “spatialized”: observed and documented, the exotic flora and fauna and non-Western races acquire meanings and find their places in a global taxonomic or encyclopedic order that reflects the evolutionary stages of development or civilization (15-16). Being “observed from the Time of the observer,” the geographical and temporal “distance” of the savage, alien others that denotes deficiency and inferiority rather than “difference” is then visibly and definitively decreed (25, 16). During the heyday of imperialism, the panoramic, evolutionist observing position of “the European observer” is vicariously taken up by the mass public, and ultimately becomes a prevailing way of knowing and representing the world. Reflecting the geographical self-centeredness and transcendent progress of “the European observer,” the symbolic predominance and pervasiveness of the Outline of History in Between the Acts suggest that heir to indigenous patrimony and tradition, the gentleman squire is also exemplary of the masculinist evolutionary zenith of “the complete Insider” that embodies the panoramically universalist public.2 Legitimately governing those lacking reason and learning by mastering the 2 As Gillian Beer argues, Virginia Woolf “disperses [prehistory] throughout the now of Between the Acts,” in which “[t]he engorged appetite of empire, the fallacy of ‘development’ based on notions of dominion or of race, are given the lie by the text’s insistence on the untransformed nature of human experience” (26, 27). 262 Concentric 38.1 March 2012 cultivated taste, the elite ruler-observer in the country observes and dominates the subordinate others enmeshed in landscape or nature inside England as well as across the globe. Like the “perfect type” of “Man” in Three Guineas “of which all the others are imperfect adumbrations,” the figure that quintessentially embodies ideal Western masculinity and explains the root cause of war, the gentleman squire at Pointz Hall as “the complete Insider” is confident in his civic preeminence and universal transcendence as underlain by his cultivated perception (Three Guineas 142). Just as he observes the country landscape, Bart Oliver’s perceptions of the ruled, inferior others who are without taste and cultivation rely on abstracted aesthetics or the panoramic evolutionist discourse that categorizes and visualizes the others in exotic, primordial space and time. And the observed others entrapped in landscape or nature in turn serve merely to illustrate the universal principles of beauty or the universal evolutionary development as commanded or topped by the cultivated ruler-observer. As object of the old squire’s gaze that represents ideal embodiment of beauty, the pictured lady beside the male ancestor seems to exist outside the vicissitudes of time; her inscrutable, unseeing eyes only lead the viewers of the picture “down the paths of silence,” “to the heart of silence” (Between the Acts 45, 50). Paradoxically, the aestheticized feminine image in domestic space is nonetheless also associated with social inferiors like the servants, the villagers, or the homosexual and the sensual woman outside the norm of the bourgeois family whose observed or visualized subordination similarly corroborates the masculinist supremacy. Much like the class others, the upper-class ladies in Between the Acts as the internal Outsiders are not just of an inferior standing compared to the gentleman squire, but also perceived in imagery of prehistoric savagery or benightedness. Clearly, the evolutionist narrative of the Outline of History that records the times “[w]hen we were savages” is echoed by the pseudo-scientific language accounting for the social stratification topped by the cultivated ruler-observer (30). Just as the “old lady, the indigenous, the prehistoric” in the country is likened to “an uncouth, nocturnal animal, now nearly extinct,” the Oliver women who are seen as tethered to native tradition and corporeality personify primitive instincts and atavistic barbarity (203, 93-94). With her devout faith, Lucy Swithin appears to resemble “a dinosaur or a very diminutive mammoth” stuck in the Victorian age; she is also teased by her brother for being too feeble-minded to comprehend the massive bulk of “English literature,” thus “leaving books on the floor” like the “donkey who couldn’t choose between hay and turnips and so starved” (174, 59). Having internalized the hegemonic masculinist view, Isa the young mother in the stable yard likewise Ching-fang Tseng 263 compares herself mournfully to the “last little donkey in the long caravanserai crossing the desert,” “burdened with what they drew form the earth; memories; possessions,” with the duty to procreate like “the great pear tree” (155). Such atavistic bestiality similarly defines the social other like sensual, vulgar Mrs. Manresa, the nouveau riche with a disreputable colonial background, who openly confides that “I’m on a level . . . with the servants,” “I’m nothing like so grown up as you are” (45), or William Dodge the homosexual who appears to Giles Oliver “a fingerer of sensations” that should be excluded from “the more civilized” (60, 111). The Eurocentric evolutionary order perceived by the elite ruler-observer categorically ordains his own supremacy and mastery over the uncultivated inferior others, indiscriminately perceived in benighted, primordial imagery. The evolutionist, racialist visualization of otherness, just like the abstracted aesthetics of taste, extinguishes the variety and vitality of life, and moreover naturalizes the hierarchized social or racial order based on the universalist gaze of “the complete Insider.” Corresponding to the commanding, panoptic “European observer” positioned at the apex of the evolutionary order, the gentleman squire as the elite ruler-observer is not just the inheritor of status and wealth ruling the rural locality, but the public man who makes claims to objectivity and universality and thus legitimately dominates the observed and ruled within and across national bounds. As James Clifford maintains, up until the early twentieth century, culture or civilization refers to “a single evolutionary process” of “humanity,” whose “natural outcome” is the “European bourgeois ideal” of the “autonomous, cultivated subject” regarded as “a telos for all humankind” (92, 93). Owing to the gentleman squire’s transcendent, universalist cultivated perception, local ruralist Englishness founded on patrilineal continuity and indigenous tradition then readily becomes synonymous with expansive universalist Englishness seen as exemplar of progress and civilization. Ostensibly representing disinterestedness and categorical truths, the cultivated perception predicated on fortune and education not merely underlies correlated internal class hegemony and masculinist power, but bespeaks the universalized superiority of the civilized “Man” or nation which spurs and rationalizes expanding, annexing imperialism. The Unsheltered House and the “Outsiders’ Society” Opposing the virile masculinism of the dictators ruling within and without the nation, Woolf’s idea of the “Outsiders’ Society” in Three Guineas aims to refuse to 264 Concentric 38.1 March 2012 “follow and repeat and score still deeper the old worn ruts” of patriarchal England (105). Founded on the threshold position of “daughters of the educated men” yet meant to be transgressively inclusive, the “Outsiders’ Society” seeks to dissolve the constricting divisions and distinctions in society as if they were “chalk marks only” (143). The Outsiders reject the hypnotizingly propagated views of the public world that not only maintain and reinforce the belligerent masculinist order but also cripple “the free action of human faculties” and stifle “the human power to change and create new wholes” (114). Intended then to be “elastic” and “anonymous,” the “Outsiders’ Society” distinguishes itself from the existent social structure by its embrace of “obscurity” as opposed to the glaring “illumination” of the masculinist public’s propagandist control (106, 114), and by its attempt to “penetrate deeper beneath the skin” to see alternative or hidden facets of reality (22). In Three Guineas, Woolf highlights the politics of looking and its centrality in the masculinist order governed by “the complete Insider.” While insisting on retaining, nurturing the free and unconstrained private looks, she argues that in order to envision a better future where all enjoy “freedom, equality, peace,” an integral aim of the “Outsiders’ Society” is to employ “private means in private” to make “critical” and “creative” “experiments” (113). And to have alternative, innovative ways of seeing and thus be able to form “new wholes,” the Outsiders depend on the artists among them “to increase private beauty,” to help them perceive “the scattered beauty” creatively assembled and arranged by the artists “to become visible to all” (113-14). Coming into being by the Outsider-artist’s triggering the shifting or deepening of people’s perceptions, the “Outsiders’ Society” is ingeniously enacted in Between the Acts through the performance of La Trobe’s village pageant and the gentry-audience’s reactions to it. The alternatively, subversively “private” visions presented and stimulated by the Outsider-artist La Trobe’s village pageant momentarily transforms the gentry-audience into a self-reflective and imaginative collectivity of the “Outsiders” for once not positioned as the privileged ruling class. Though the village pageant as an annul local tradition signifies the continuity of the way of life in rural England and is a popular nationalistic form of drama mainly performed on Empire Day in Woolf’s time, 3 La Trobe’s village pageant 3 Julia Briggs points out that “[f]or Woolf, the pageant was simultaneously old and new: its roots were in ‘the old play that the peasants acted when spring came,’ but the historical pageant had been reinvented in the early twentieth century by Louis Napoleon Parker, and had since become hugely popular as a local activity”; and that “[d]uring the 1930s, many small towns and villages acted out their own supposed pasts in secular pageants, often performed on Empire Day (24 May), though they could reflect a range of political attitudes” (384). Ayako Yoshino notes that Ching-fang Tseng 265 nevertheless innovatively contests the hegemonic cultivated perception epitomic of Englishness and civilization. By presenting, provoking the de-familiarized and performative visions of landscape and “Ourselves,” it divests the gentry-audience of their ingrained, naturalized class self-image as represented by Pointz Hall. Despite its faithfulness to the canonized ethos and motifs of the historical periods, La Trobe’s pageant as a playful, parodic dramatization of English history and literature, of “our island history” customarily likened to organic human growth and birth (76), is a deliberate yet contingent “experiment” meant to “[make] them [the audience] see,” that is, to spark unconventional, creative visions of self and community, home and civilization (179, 98). While set against the scenic backdrop of the view, La Trobe’s outdoor village pageant enacting English history and literature nevertheless does not intend to make the gentry-audience “see” what attests to their distinction and glories, so much as how they as a whole have shared a delusional and less than honorable class self-identity, founded on the hegemonic narrative of England and Englishness or the cultivation of taste. Analogous to “the shelter of the old wall” in the garden where Bart Oliver authoritatively guides his guests to apprehend landscape views, the painted wall in the pageant’s last act triumphantly symbolizes “Civilization” (52, 181). As Mr. Page, the reporter personifying the reigning public views of “the complete Insider,” confidently scribbles in his notebook, the wall with a ladder surrounded by diligently working men and women of different races “conveyed to the audience Civilization (the wall) in ruins; rebuilt . . . by human effort”; altogether “they signify” some “League” of venerable trans-national collaboration (181-82). In the meantime, the gentry-audience applauding the spectacle symbolic of universally emancipatory, humane civilization regards it as a “flattering tribute to ourselves,” thinking it no doubt reflects “what the Times and Telegraph both said in their leaders that very morning” (182). Yet just as the abrupt break and change of music lead to snappy, cacophonic sounds and rhythms, or the suddenly emerging mirrors from the bushes mock and fissure the gentry-audience’s elite class self-image, “the old vision” represented by the deceivingly all-inclusive civilization is relentlessly “shiver[ed] into splinters,” and what it perceives as “whole” “smash[ed] to atoms,” by the pageant’s parodic disruption of the historicist, universalist narrative of Englishness and the aesthetic perception of landscape naturalizing the ruralist vision “[d]iscussion of the Parkerian pageantry by its contemporaries makes it clear that it was seen at least initially as a nationalistic form of drama,” and its “emphasis shifted between the democratic potential of the pageant and its role in reinforcing communities, its use as a tool for teaching local and national history, and perhaps most commonly, as locus of patriotic sentiment” (51). 266 Concentric 38.1 March 2012 of home (183). To debunk and challenge “the old vision” of the actually discriminatory “Civilization” bespeaking the hegemonic cultivated perception means contestation of the ruling gentry’s fixed, complacent class self-image imaginarily mirrored by the view, as well as deflation of the transcendent, masculinist prominence of the cultivated ruler-observer topping the universal evolutionary development. With her creative power that “seethes wandering bodies and floating voices in a cauldron, and makes rise up from its amorphous mass a re-created world,” the Outsider-artist La Trobe audaciously experiments with the Olivers’ estate’s outdoor space, turning it into an open theater which then ceases to be the aesthetically constructed and perceived lands indicative of class privilege (153). The landscape view is hence de-familiarized and the estate’s outdoor space re-created as a lively and occasionally chaotic stage performing national history and literature. It becomes a dynamic, performative space newly inscribed onto the aestheticized country scenery, a nearly uncharted natural space now denuded of the abstracted aesthetic meaning and the naturalized, territorialized historical consciousness that have underlain the ruling gentry’s class hegemony. Moreover, the Outsider-artist’s village pageant collapses the boundary between the cultivated ruler-observer and the demeaned, primitivized ruled and observed, thereby demolishing not only the elite class self-image of the gentry-audience but also the “perfect type” of “Man” that epitomizes it. And as it parodies the hegemonic cultivated perception of aestheticized landscape and historical progress, La Trobe’s pageant moreover foregrounds interruptions and “present-time reality” to counter eternalized historicist continuity and teleology (179). Surveying the country estate’s outdoor space, La Trobe has told its owner Bart Oliver: “There the stage; here the audience; and down there among the bushes a perfect dressing room for the actors,” and the terrace is “the place for a pageant” which allows the villager-actors’ “[w]inding in and out between the trees . . .” (57). On the June day of its performance, the outdoor village pageant consequently has to constantly compete with the landscape view for the gentry-audience’s attention and appreciation. Instructing the villager-actors in the bushes, the playwright senses that “[m]any eyes looked at the view,” and “[o]ut of the corner of her eye she could see Hogben’s Folly; then the vane flashed” (151-52). Such tension is deliberately created in the playwright’s experiment to obstruct and de-familiarize the gentry-audience’s accustomed perception of the landscape. Watching the terrace-stage which is part of the view, the gentry-audience seated in rows enjoys the pageant but in the meantime has to face between the acts altogether “the empty Ching-fang Tseng 267 stage, the cows, the meadows and the view, while the machine ticked in the bushes” (177). As they are looking at the view as usual, the gentry-audience also has to confront the disconcerting emptiness of the terrace-stage, where the acted-out uneventful “present time” nullifies the timeless natural beauty and harmony of home, and the monumental historical scenes that interpellate the gentry-audience repeatedly affirm their notions of Englishness and class self-identity. As La Trobe “wanted to expose them, as it were, to douche them, with present-time reality,” not only does the gramophone blare the music “Dispersed Are We” whenever an interval starts, but between the acts and during the last act “Present Time. Ourselves” the gentry-audience intensely experiences the real, non-dramatic present time and suddenly feels ill at ease with their familiar sense of self (179, 95). Facing the terrace-stage stripped of the pageant’s historical spectacles as well as the eternalized beauty of the view, they feel “a little not quite here or there”; they “sat exposed” and “[a]ll their nerves were on edge,” as if “[t]hey were neither one thing nor the other,” “suspended, without being, in limbo” (149, 178). And the gentry-audience’s elite class self-image of “Ourselves” is not just problematized but powerfully invalidated and pulverized, when all the villager-actors are coming out from the bushes, holding “[a]nything that’s bright enough to reflect” the unguarded, fragmented images of “ourselves,” still in the guises of the noble and commoner characters from the different ages and declaiming lines or phrases of their roles (183, 185). The gentry-audience is unwillingly confronted with the “awful show-up” as “[t]he hands of the clock had stopped at the present time,” and the unflattering, disintegrated class self-image exposed in the suspension of the historical progress fully alienates them from their petrified social identification (184, 186). Moreover, in the midst of “the jangle and the din” when the “cows” and “dogs” also excitedly join the commotion, “the reticence of nature was undone, and the barriers which should divide Man the Master from the Brute were dissolved” (184). In the Outsider-artist’s “little-game” that ferociously parodies, challenges the soul-reflecting mirrors in the country gentleman’s library, the shifting, unrelenting mirrors from the bushes overturn as well the panoptic, civilized eminence of “Man the Master,” the discerning, autonomous universal public subject representative of “Ourselves” with which the audience identifies (186). Instead of being prominently positioned above “the Brute” or the categorically classified or abstracted nature, the cultivated “Man” is placed right among the supposedly dominated and observed. The blurring of the distinctions of nature and the performing stage, of the cultivated observer and the uncivilized observed within landscape or nature, cancels the universalist, masculinist objectivity and transcendence, and accordingly subverts 268 Concentric 38.1 March 2012 the representative authority and dominance of the gentleman squire. Now as a whole unrestricted by received ideas or training and constituted by anonymous and performative identities, the gentry-audience watching the Outsider-artist’s pageant not merely confronts disillusioning, fracturing self-reflecting mirrors, but also sees beyond the eternally illumined surface of the lily pool to perceive the lively, ordinary beauty of the villagers and everyday life. In the dwindling “light of evening that reveals depths in water,” the gentry-audience at the end of the pageant then stands facing the “linger[ing],” “mingl[ing]” villager-actors (196, 195). As if the class divide no longer exists and constrains one’s perception, the gentry-audience notices the random, dynamic beauty of the villager-actors that “[e]ach still acted the unacted part conferred on them by their clothes” (195). They perceive that “[b]eauty was on them,” “[b]eauty revealed them,” and also see the exceptional beauty rather than irking unsightliness of “the red brick bungalow radiant” (195-96). Dislodged from the elevated observing position at the country house from which to appreciate landscape views, the gentry-audience meanwhile is instead looking at Pointz Hall, as if penetrating “the golden glory” to have a glimpse of “a crack in the boiler” and “a hole in the carpet,” of the ordinary and quotidian that have been hidden from the cultivated observer’s purview (197). And before the unrehearsed, transgressive perception of home and “Ourselves” eventually dissipates, the gentry-audience applauds not only the characters “Budge and Queen Bess,” but also “the trees; the white road; Bolney Minster; and the Folly” (197). Until the gramophone’s equivocal last refrain “Unity-Dispersity” that characterizes the unbounded, anonymous “Outsiders’ Society” fully dissolves the assembly, the aestheticized home landscape has once appeared, if only transitorily, as impermanent and improvisational as the stage and performance of the village pageant (201). Though intended to de-familiarize and contest the hegemonic views of “Ourselves,” Englishness, and civilization, the village pageant nonetheless does not impose a predominant vision on its audience. Rather, it is purposely made to be de-centered, polyvocal, and open-ended so as to arouse and inspire multiple and divergent reflections. Further, as the pageant’s venue and success are markedly contingent upon the weather in Between the Acts, La Trobe is not always in control of the “[i]llusion” it creates (140); she is unable to preclude its unexpected effects since at times “[h]er vision escaped her” and her audience is “slipping the noose” (98, 180). Apparently free from the totality of meaning and organicist closure that the commanding cultivated perception decrees, the Outsider-artist’s work does not abide by the abstracted rules of taste and is subject to unforeseen, random Ching-fang Tseng 269 interruptions.4 More important, together with its contingent effects, the pageant’s intended experiment, its cacophonies and open-endedness, provokes the diversely inspired, confounded, or disapproving reactions and interpretations from the gentry-audience, which amount to a communal collaboration of meaning and vision of the Outsiders as the “orts, scraps and fragments” unbounded by class privilege and supremacy (188). Speaking “only as one of the audience, one of ourselves,” the Rev. Streatfield humbly offers his interpretation of the pageant: “We act different parts; but are the same. . . . I thought I perceived that nature takes her part. Dare we, I asked myself, limit life to ourselves?” (191). Among the dispersing gentry-audience, the anonymous, fragmented voices also are discussing the purport of “Ourselves” that has been unsettlingly explored by the pageant: “Did you understand the meaning? Well, he said she meant we all act all parts”; “He said she meant we all act. Yes, but whose play? Ah, that’s the question! And if we’re left asking questions, isn’t it a failure as a play?” (197, 199-200; emphasis in original). And at Pointz Hall, “[s]till the play hung in the sky of the mind—moving, diminishing” after dinner; the family “all looked at the play” and “[e]ach . . . saw something different” (212, 213). Whereas Bart Oliver assuredly remarks that it is “[t]oo ambitious” “[c]onsidering her [La Trobe’s] means,” the Oliver women chatting about the pageant are uncertain whether it is true “what he said: we act different parts but are the same” (213, 215). Furthermore, with Between the Acts’s blurred and discontinuous boundary between the pageant and the novel that disallows textual closure and authorial control, the Outsiders’ alternative private visions are not just facilitated and provoked by La Trobe’s village pageant. They are presented as well in the narrative when the characters are having their private moments, then not merely the audience of the pageant. In his country gentleman’s library, the old squire has a gratifying dream of his bygone colonial venture in which he sees “as in a glass, its luster spotted, himself, a young man helmeted” (17). The dream thrillingly enacts his exploit in the wild land, and nostalgically brings back “youth and India”: the young Bart Oliver as a colonial explorer holds “a gun” “in his hand,” facing “a hoop of ribs” “in the sand,” “a bullock maggot-eaten in the sun,” and the “savages” “in the shadow of the rock” (17). Ironically indicating the supposed origins of civilization 4 As Joplin suggests, in Between the Acts, “Woolf forces the likeness of woman playwright to fascist dictator to press her recognition of her own will to power as practicing author,” and at the same time, though, the playwright is also “the author as anti-fascist . . . [who] celebrates the intrusion of nature’s wild and uncontrollable whims to counter the fixity of social behavior,” as she “stops resisting the freedom of the wind, the rain, the instincts of the grazing animals . . . [and] treats meaning as shared, as mutually generated by author, players, and audience” (90). 270 Concentric 38.1 March 2012 are nothing less than a breeding ground of imperialist impetus and aggressivity, the gentleman squire’s dream vision corresponds with the domesticated woman’s vision of rape which occurs similarly in the country gentleman’s library. Browsing the Times in her father-in-law’s library, Isa accidentally reads about the news that a girl was raped by the soldiers in the barrack room at Whitehall. Startled by its horrific details, which are “so real” and soon surmount her expectation of a “fantastic,” “romantic” story, she cannot help but imaginarily sees the rape scene “on the mahogany door panels” (20). Moreover, the weapon she imagines to have been used by the girl “screaming and hitting [one of the troopers] about the face” is in her mind’s eye conflated with the hammer carried by Lucy, who at this point suddenly opens the door and walks in the room (20). Isa’s envisaging of the heinous crime at the locus symbolic of state power and order and its textual association with the “educated man’s daughters” implies that, as Woolf argues in Three Guineas, terror and tyranny are not extrinsic so much as internal as the dictators in England share hidden affinities with those in Nazi Germany. Like the pageant’s disillusioning, de-centering mirrors from the bushes, the alternative Outsiders’ visions of the country gentleman’s library reveal it as barbaric space of unseen or concealed violence, forcefully subverting the differentiation between civilization and atavistic benightedness and savagery. Another alternative Outsider’s vision that reveals the gentleman squire’s barbarity and brutality rather than enlightenment and civility is presented in the narrative, when Bart Oliver is dexterously and unselfconsciously exercising his colonialist virility and peremptoriness in the garden. Masquerading as “a terrible peaked eyeless monster” behind the morning paper folded into a “snout,” the old squire suddenly comes up and mercilessly violates his grandson George’s tranquil, joyful universe of plenitude in the garden (Between the Acts 11-12). Then, “appear[ing] in person” and yelling “Heel! . . . heel, you brute!,” the retired colonial administrator manages to subdue “among the flowers” Sohrab the Afghan hound scarcely distinguishable from little George, who is meanwhile terrified and bursts out crying (12). Notably, no sooner had Bart Oliver noted that “[t]he boy was a cry-baby” after his relentless act of coercion than he began to read the “smooth[ed] out” “crumpled paper” while intermittently marveling at the picturesque beauty of the landscape views (13). In venting his hatred of the degenerate others, Giles ferociously stamps on the snake “choked with a toad in its mouth” perceived as “a monstrous inversion” and secretly has the “white canvas on his tennis shoes” uglily “bloodstained” (99). Just like his son who inherits his property and status and also masculine assertiveness, Bart Oliver’s clandestine exerting of his brutish virile force Ching-fang Tseng 271 turns the newspaper as well as the aesthetically “[f]ramed” “picture” of landscape under his cultivated gaze into nothing but undisclosed vehicles of irrationality and barbarity (13). Interwoven into and splitting the narrative of Between the Acts, the Outsider-artist La Trobe’s pageant that withstands totality of meaning finds its message multivocally, variedly echoed by the narrative visions of the individual characters in their private moments. Moreover, the novel’s counter-totalizing anti-closure culminates in ultimately dissolving the distinction between the pageant and the novel that equally seek to present and foster alternative Outsiders’ perceptions, as well as self-reflexively draw attention to the provisionality, partiality, and constructedness of the Outsider-artist’s own vision. As the day is darkening, Isa again visualizes in her mind not just the pageant, but also the haunting scenario of the struggling girl who “had gone skylarking with the troopers” at Whitehall (216). While Pointz Hall is losing its command of views in the dusk, Isa reflects upon the pageant’s possible meanings and still wonders “[w]hat then” happened afterwards to the raped girl (216). Her concurrent envisaging of the rape and the village pageant throughout the day underscores the discreteness and yet interpenetration of the novel’s manifold layers, intended to arouse divergent and multiple interpretations that enact the unbounded, creative “Outsiders’ Society” whose unity consists in its resistance to the tyrannical hegemonic perception (215). Correspondingly, the playwright La Trobe in the dusk perceives the house’s imminent lapsing into darkness and then looks at the country landscape realistically as “land merely, no land in particular” (210). Yet the sight of the land provides inspiration for La Trobe’s new play: walking toward the gate of Pointz Hall, she senses “something rose to the surface,” and suddenly has a glimpse of its first scene which contains “two scarcely perceptible figures,” “half concealed by a rock” beside “the high ground at midnight” (212, 210). “[A]lways” having “another play” lying “behind the play she had just written,” La Trobe envisions her next play taking shape before Between the Acts comes to its close, and moreover its first scene coincides with the unfolding domestic quarrels and intimacy of Isa and Giles which end the novel (63). In the desolate, prehistoric open fields where “[t]he house has lost its shelter,” the young couple at Pointz Hall that presumably symbolizes the future of England and civilization will be confronting each other after a day’s unspoken rancor and jealousy, like “the dog fox” and “the vixen” fighting “in the heart of darkness, in the fields of night” (219). In the primordial darkness, the couple has lost their cultivated semblance and prominent observing position and instead becomes a spectacle as 272 Concentric 38.1 March 2012 actors on stage about to reveal their story as yet untold. The darkness that eventually engulfs Pointz Hall conflates Woolf’s open-ended narrative with La Trobe’s next play, and at the same time also bridges the village pageant that is just finished and the evolving new play confusing reality with the performing stage. It clearly reverses and parodies the evolutionist plot of the Outline of History and intimates the precariousness, fictionality, and corruption of the hegemonic perception of Englishness and civilization. Yet as contrasted with the glaring “illumination” emanating from the elite ruler-observer, the darkness also points to the Outsiders’ alternative visions that are textually enacted through the novel’s conspicuously interrupted, multi-layered, and open-ended structure. As the multi-perspectival and even anti-perspectival novel self-reflexively highlights its playful constructedness and heterogeneous “orts, scraps and fragments” of voices and perceptions that simultaneously contest the oppressive hegemonic view and situate the Outsider-artist’s own vision, it embodies and also enables the “Outsiders’ Society” that critically and collaboratively engages in the innovative, private interpreting and imagining of meaning. Between the Acts’s at once foreboding and self-referential closing scene of primordial darkness thus does not univocally symbolize or prophesize civilization’s degenerate retrogression under the looming threats of war and annihilation, as many critics have argued.5 The staged, (un)framing prehistoric darkness is also a parodic reversal of the complacent hegemonic class self-image epitomic of Englishness and the evolutionist telos of civilization. Moreover, it emblematizes, like the boundary-exploding, multifarious mirrors from the bushes, the replacing of the commanding cultivated perception with the emergent, pluralistic views of the Outsiders. After playfully, multi-vocally unveiling the repressiveness and incompleteness of the cultivated gaze and its underlying brutality and instinct of domination, the novel envisages the full dismantling of the bounds of civilization as Pointz Hall or the civilized self-image of “Ourselves” can no longer distinguish itself from prehistoric savagery. Further, it proposes an alternative sense of 5 Many critics have noted the temporally backward-moving degeneration at the end of Between the Acts. As Judith Johnston argues, “The terrifying movement backward in historical time at the end of Woolf’s novel reflects Marlow’s opening strategy in his narrative, drawing his audience back to an England that seemed uncivilized to a Roman commander” (273). Mark Hussey points out that “the book actually moves backwards although it is apparently progressing,” and “[a]t the close, Isa and Giles have been abandoned by their ‘island story’” (251; emphasis in original). Sallie Sears remarks that the rape story in the newspaper “haunts Isa throughout the day and presages the brutal lovemaking between herself and Giles and the novel’s conclusion—a scene that both initiates and symbolizes the work’s vision of a collective return to the savagery of the past” (215). Ching-fang Tseng 273 “Ourselves” based not on a shared taste or lifestyle but on a common recognition of the human vulnerability and savagery faced with the menace of war, as well as on the Outsiders’ insistence on maintaining and generating creative, discrete visions that counter the hypnotizing hegemonic perception dominating the masculinist public. Refusing to be “the passive spectators doomed to unresisting obedience” (Woolf, Three Guineas 142), the anonymous, dynamic “Outsiders’ Society,” by the help of the Outsider-artist, collectively produces and imagines the “private beauty,” the innovatively combined “scattered beauty” that has been occluded or unseen by the predominant “complete Insider” (113, 114). As Woolf agues in “Thoughts on Peace in an Air Raid” written in August 1940, to prevent war and secure a future for people in England as well as across the national borders, it is essential to “fight for freedom without firearms,” to “fight with the mind,” with “mak[ing] ideas” (244). Between the Acts envisions the dissolving of constricting, repressive boundaries and distinctions, the possibility of the “Outsiders’ Society” as the “new wholes” composed of the resistant spectators who seek to preserve and nourish the human power to see differently and to think freely. Works Cited Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Rev. and extended ed. London: Verso, 1991. Barrell, John. The Idea of Landscape and the Sense of Place. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1972. —. “The Public Prospect and the Private View: The Politics of Taste in Eighteenth-Century Britain.” Reading Landscape: Country-City-Capital. Ed. Simon Pugh. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1990. 19-40. Beer, Gillian. Virginia Woolf: The Common Ground. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1996. Bermingham, Ann. Landscape and Ideology: The English Rustic Tradition, 1740-1860. Berkeley: U of California P, 1989. Briggs, Julia. Virginia Woolf: An Inner Life. London: Penguin, 2006. Caughie, Pamela. Virginia Woolf and Postmodernism: Literature in Quest and Question of Itself. Chicago: U of Illinois P, 1991. Clifford, James. The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1988. Davidoff, Leonore. Worlds Between: Historical Perspectives on Gender and Class. New York: Routledge, 1995. 274 Concentric 38.1 March 2012 Eagleton, Terry. The Ideology of the Aesthetic. Cambridge: Blackwell, 1990. Esty, Jed. A Sinking Island: Modernism and National Culture in England. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2004. Fabian, Johannes. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object. New York: Columbia UP, 1983. Froula, Christine. Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Avant-Garde: War, Civilization, Modernity. New York: Columbia UP, 2005. Helsinger, Elizabeth K. Rural Scenes and National Representation: Britain, 1815-1850. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1997. Howkins, Alun. “The Discovery of Rural England.” Englishness: Politics and Cultures 1880-1920. Ed. Robert Colls and Philip Dodd. London: Croom Helm, 1986. 62-88. Hussey, Mark. “‘I’ Rejected; ‘We’ Substituted: Self and Society in Between the Acts.” Virginia Woolf: Critical Assessments. Vol. 4. Ed. Eleanor McNees. Mountfield: Helm Information, 1994. 242-53. Jay, Martin. “Scopic Regimes of Modernity.” Vision and Visuality. Ed. Hal Foster. New York: New Press, 1999. 3-23. Johnston, Judith L. “The Remediable Flaw: Revisioning Cultural History in Between the Acts.” Virginia Woolf and Bloomsbury: A Centenary Celebration. Ed. Jane Marcus. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1987. 253-77. Joplin, Patricia Klindienst. “The Authority of Illusion: Feminism and Fascism in Virginia Woolf’s Between the Acts.” South Central Review 6.2 (1989): 88-104. Mitchell, W. J. T. “Introduction.” Landscape and Power. Ed. W. J. T. Mitchell. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1994. 1-4. Potts, Alex. “‘Constable Country’ between the Wars.” Patriotism: The Making and Unmaking of British National Identity. Vol. 3 Ed. Raphael Samuel. London: Routledge, 1988. 160-88. Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. New York: Routledge, 1992. Pridmore-Brown, Michele. “1939-40: Of Virginia Woolf, Gramophones, and Fascism.” PMLA 113.3 (1998): 408-21. Said, Edward. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Vintage, 1994. Sears, Sallie. “Theater of War: Virginia Woolf’s Between the Acts.” Virginia Woolf: A Feminist Slant. Ed. Jane Marcus. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1983. 212-35. Silver, Brenda. “Virginia Woolf and the Concept of Community: The Elizabethan Playhouse.” Women’s Studies 4 (1977): 291-98. Williams, Raymond. The Country and the City. New York: Oxford UP, 1973. Ching-fang Tseng 275 Woolf, Virginia. Between the Acts. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1969. —. The Diary of Virginia Woolf, Volume Five: 1936-1941. Ed. Anne Olivier Bell. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1985. —. “The Green Mirror.” The Essays of Virginia Woolf, Volume Two: 1912-1918. Ed. Andrew McNeillie. London: Hogarth, 1987. 214-17. —. “Thoughts on Peace in an Air Raid.” The Death of the Moth and Other Essays. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1942. 243-48. —. Three Guineas. London: Harcourt Brace, 1966. Yoshino, Ayako. “Between the Acts and Louis Napoleon Parker—the Creator of the Modern English Pageant.” Critical Survey 15.2 (2003): 49-60. Zwerdling, Alex. Virginia Woolf and the Real World. Berkeley: U of California P, 1986. About the Author Ching-fang Tseng is Assistant Professor in the English Department of National Taiwan Normal University. She specializes in nineteenth- and twentieth-century British literature, post-colonial literature, and literary modernism. Her work in progress is a book-length project that studies representations of Englishness and home in Virginia Woolf and a number of post-colonial writers in a comparatively trans-national context of empire. [Received 20 March 2011; accepted 15 December 2011]