The Molson- Coors: A Case Research of Two Family Firms

advertisement

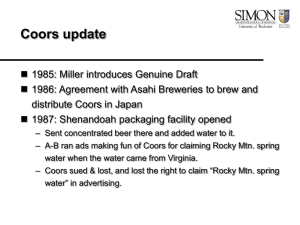

The Molson- Coors: A Case Research of Merger between Two Family Firms This case captures a rare picture of merger between two of the oldest family business in North America, the Molson and the Coors family businesses each with its own unique culture. The case tracks the two businesses since their inception by the two entrepreneurs/founders to the current generation and the events leading to the merger. It provides some insight into the motive behind the merger and the performance of these two family businesses before and after the merger. The case sheds some light on the common characteristics and background that have allowed these two firms to survive for generations as family-controlled businesses. In 2004, Molson Inc. started discussions with America‟s family-owned Coors Brewing Company for a possible merger (The Economist, 2004). Both companies‟ flagship beers (Coors Light in the U.S. and Molson Canadian in Canada) had been losing market share, but also both Coors and Molson individually lacked the capacity to face the consolidation trend in the global brewing industry (McArthur, 2005; McKenna, 2004). As news of the potential merger of equals emerged in July 2004, industry analysts were questioning the merits of such a merger, “Can Adolph Coors Co. come to the rescue of Molson Inc.? Or vice versa? Or is the proposed merger of the two faltering North American brewing companies really more about „maintaining family business empires‟?” (Marotte, 2004). Reid (2004) noted that the merger is more about brewers‟ pride that reflects generations of family breweries in an industry dominated by family businesses. Both Eric Molson, Chairman of Molson Inc. and Peter Coors, Chairman of Adolph Coors Company felt that the merger is strategically compelling, allowing two of the oldest family brewing businesses in North America to survive. However, the merger created a rift in the Molson family over its benefits (Silcoff, 2004a). Commenting on the merger, Karen Molson, the family‟s historian said, “What do I think; what do I feel about [the merger]? It saddens me a lot. From my perspective it‟s very regrettable this is all happening. Molson is the oldest familyowned business in Canada. As a historian I valued that very much, and as a family member. I guess a business person might look at that and say it‟s sentimentality. But to me, it‟s far more than that. It‟s a link to our past, to our whole country‟s past. Just the idea of breaking the continuity gives one a sense of loss” (Silcoff, 2004a). The Molson Family Business Molson Inc. was founded by John Molson Sr., an immigrant from England who settled in Montreal and started his brewery business in 1786. The brewery did well due to the founder‟s commitment to quality and innovation (Woods, 1983; 1 Molson, 2001). Over two hundred years and seven generations, the Molson family business grew to a phenomenal level and became the oldest and one of the largest family businesses in Canada. Figure 1 provides a simplified family tree reflecting succession and key family members involved in the Molson family business. John Sr. mentored his three sons: John Jr., Thomas and William at an early age. The sons followed in their father‟s footsteps and entrepreneurial behavior. They ventured into other businesses, but the brewery was the core of the family business (Hunter, 2001; Denison, 1955). John Sr. instilled in his sons strong values such as hard work, honesty and integrity. These values played a critical role in shaping the ethical behavior of future generations. Each generation was guided by these values which contributed to the development of a strong family business culture (Hunter, 2001; Molson, 2001). As the second generation became well versed in the business, John Sr. withdrew gradually from the family business and focused on community service and philanthropy (Woods, 1983). The gradual retirement of the older generation and their commitment to community service became a critical part of the Molsons‟ culture. It has allowed the older generation to gradually exit the family business and to focus on serving their community and for the younger generation to take over the family business in a smooth fashion. This tradition has never been violated for over 200 years. The second generation led by Thomas and William Molson expanded the family business while grooming the third generation – John Henry Robinson (JHR) as well as his siblings and cousins (Woods, 1983). The grooming process which was long and extensive, required that all the members start at the bottom following the tradition started by the grandfather and founder John Sr. The grooming process included a formal education in science followed by training at the United States Brewing Academy as well as an apprenticeship at the brewery or at other family business breweries. This approach has been a defining character of the Molsons for over 200 years (Molson 2001; Denison, 1955; Woods, 1983). JHR‟s apprenticeship at the brewery lasted three and one-half years and the notarized agreement spelled out the expectations, compensation and benefits. Both his father Thomas and his Uncle William provided the mentorship (Denison, 1955; Molson, 2001). JHR succeeded his father and formed a partnership with his brothers Markland and John Thomas. The brothers decided to close down the distillery which was acquired a few years earlier rather than compromise their principles and falsify the company‟s tax returns as their competitors were doing (Woods, 1983). This ethical approach has been the cornerstone of the Molsons‟ approach to business for over seven generations. Following the closure of the distillery JHR and his younger brother John Thomas focused on expanding their core business, the brewery. Further, they began mentoring the fourth generation, Fred and Harry (Markland‟s sons) and later on Herbert (John Thomas‟ son) who eventually took over the family business following JHR‟s death (Denison, 1955; Woods, 1983; Molson, 2001). 2 In the late 1890‟s, Herbert and his cousin Fred embarked on modernizing and expanding the brewery at a cost of $2.5 million (Woods, 1983; Molson 2001). The two cousins, also began mentoring the fifth generation, Tom (Herbert‟s son), who was groomed to succeed his father as well as Fred‟s sons, John Henry and Bert (Woods, 1983; Molson 2001). With the end of the prohibition era beer sales increased and the Molsons decided to expand the brewery from its modest 7.5 million gallons. Herbert appointed the younger generation, Tom and Bert, to manage the project during the Great Depression of the early 1930s (Woods, 1983). Following the death of his cousin Fred, Herbert focused his efforts on making the family business more strategically competitive. He introduced modern techniques in advertising and management and improved the strategic posture of the company (Denison, 1955). As a member of the Board of McGill University, Herbert also spent a great deal of time along with his younger son Hartland to turn around McGill University which was on the verge of bankruptcy. Like his ancestors, Herbert‟s principled approach to business was demonstrated in the way he treated his competitors to the extent of saving their business when they were in trouble (Woods, 1983; Denison, 1955; Molson, 2006). Following the death of Herbert Molson in 1938 his two sons Tom, who was groomed to succeed his father, and his younger brother Hartland decided to follow the Molson tradition that the welfare of the brewery must come first and that only the best person, based on experience and managerial skills, should be selected to succeed Herbert (Woods, 1983; Molson, 2006). Their cousin Bert had extensive experience in the brewery and thus was selected to lead the family business. Bert, his brother John Henry, his cousins Tom and Hartland continued to expand the family business. Professional management was introduced as well as an employee benefits program. Both Tom and Hartland spearheaded an expansion strategy that resulted in tripling the production capacity and the modernizing of the equipment (Woods, 1983). Furthermore, Bert and the family decided to go public. That decision was motivated by two reasons, first, to resolve the succession duties problem resulting from the substantial amount of retained earnings and very small number of outstanding common stocks with no preferred and no bonds and; second, to raise additional capital for the expansion. To maintain control of the business, the family decided to create two classes of shares: non-voting A-shares and voting B-shares (Library Archives Canada, Molson Archives, MG III 57, Vol. 373-374). Following the tradition that only the best is selected for the top job, Bert hired a consultant to select a successor among his two cousins, Tom and Hartland, as well as his brother, John Henry (Molson, 2006). Hartland was appointed because of his interpersonal, financial and negotiation skills. He reshuffled the family business board to include both family and non-family members (Molson, 2006). Hartland then, embarked on a series of acquisitions of small family business breweries and expanded the business to Ontario by building a large and modern brewery in Toronto, making Molson the largest brewery in Canada. Hartland‟s strategy was to transform the family business from a local business to a national 3 brewery (Woods, 1983; Molson, 2006). Hartland was also a national World War II hero, a senator and a prominent figure in the Canadian scene. In 1958, the two brothers, Tom and Hartland, established the Molson Foundation in order to continue to carry on the social and philanthropic activities that have been a key characteristic of the Molsons. Hartland also devoted time to groom his younger cousin, Percival Talbot (P.T.), and his nephew Eric, Tom‟s son (Woods, 1983; Molson, 2006). At age 44, P.T. succeeded Hartland as President of the family business in June 1966, but died unexpectedly two months later. Since P.T.‟s untimely death, a series of non-family executives have been appointed President of the company, while the Molsons have turned their focus more towards the family business board, occupying board seats, chairman and vice-chairman of the Molson‟s Board of Directors (Molson, 2006). For over two decades the Molsons followed the diversification trend of the 60s and 70s. A number of non-family presidents were brought in to develop and implement a diversification strategy. However, by the 1980s the family business initiated a divestment strategy and a restructuring program aimed at moving away from non-core businesses and refocusing on the brewery business (Molson, 2006). Sixth generation Eric Molson, who by then had succeeded his father Tom as vice-chairman and later chairman of the board turned his efforts towards two issues, taking control of the family business and refocusing the company‟s strategy into its core business – the brewery (Molson, 2001). Over the years, the family had lost control of the business and in 1975, according to Woods (1983), the Molson family only controlled 35% of the voting stocks due to stocks dilution as well as share price decline from the diversification strategy pursued earlier. As a result, Tom and later on Eric and his siblings embarked on switching A shares (non-voting) for B shares (voting) in order to raise family control of the business (Wood, 1983). Eric‟s second task was to refocus the family business strategy on its core business and “pure play brewer” that is capable of becoming a large player (Weber, 1997). Efforts were made to buyout stakes in Molson brewery from both Foster which held over 40% stake and Miller which held 20% stake in Molson Brewery. To pay for its buyout strategy, Molson engaged in a program aimed at cost cutting as well as divesting its stake in Home Depot and other investments outside the brewery industry. In 1999 Molson abandoned its sponsorship of Hockey Night in Canada and Labatt, its main competitor, took over the hockey telecast (Alden, 1999). Molson also sold 80% of the Montreal Canadian Hockey Franchise and arena (Deacon, 2001). By the end of 2001, Molson‟s strategy of retaking control of the family business through buyout and its focus on strengthening the core business, the brewery, was achieved successfully. In 2002, Molson reported sales and profit of $2.1 billion and $209.1 million respectively (Molson, 2003). Molson was now ready to establish itself as a global player in a competitive industry controlled mostly by family owned firms. The American market offered Molson growth opportunities, given that the domestic Canadian beer market was saturated with limited opportunities for expansion. The Molsons started searching for a partner that 4 shared characteristics and a background similar to theirs. The Molsons had prior agreements with the Coors family business and have come to respect and appreciate the Coors family and their background. The Coors Family Business The Adolph Coors Company was ranked in 2003 among the 500 largest public companies in the United States with revenue close to $4.0 billion. It operates the Coors Brewing Company, the third largest brewer in the American market, as well as Coors Brewers Limited, the second largest brewer in the United Kingdom (Coors, 2003). With its headquarter and brewery in Golden, Colorado, Coors has been brewing beer in the Rocky Mountains since its inception in 1873. However, the Coors family feared that the survival of their family business was threatened by the consolidation trend that has been reshaping the beer industry since the 70s. When interviewed about the firm‟s strategy, Bill Coors, Past Chairman of Coors answered that, “our long-term strategy is to survive” (The Economist, 1978). Figure 2 provides a simplified family tree reflecting succession and key family members involved in the Coors family brewing business. The Coors Brewing Company was founded by Adolph Coors, a German immigrant who arrived as a stowaway to the United States in 1868 with a dream to build his own brewery. As with John Molson, his uncompromising commitment to brewing quality beer laid the foundation not only for the brewery‟s future growth, but also the philosophy that shaped later generations of the Coors family (Baum, 2000; Banham, 1998). This philosophy towards quality included using the best natural barley, Rocky Mountain spring water, and a dedication towards maintaining the original fresh taste of the beer, regardless of costs. This tradition would guide the family business for the next 100 years. The brewery‟s growth was also based on Adolph‟s assessment that vertical integration, from roasting its own malt, to bottling the beer, and storing the beer in an artificial ice plant, was the only way to keep control of the beer‟s quality. He was quoted as having said “the more we do ourselves, the higher quality we have,” (Baum, 2000, p. 8). As with the Molsons, Adolph three sons, Adolph Jr., Grover, and Herman became involved in the family business at a young age. Of the three sons, Adolph Jr‟s personality was similar to that of his father (Baum, 2000; Banham, 1998). Both father and son had few interests outside the brewing business and were both obsessed with quality. While Adolph apprenticed as a brewer at the Wenker Brewery, he sent all three sons to Cornell University to study chemical engineering, a trend that was followed by subsequent generations of Coors family sons. All three sons returned to work at the brewery after their university studies, but Adolph Jr. was his father‟s right-hand man. When prohibition started in 1916, Adolph who treated his workforce of mainly German immigrants as members of the family kept them working by switching from making beer to making malted milk. 5 Second generation Adolph Jr. was in his fifties when prohibition ended. He had kept the family business running throughout the depression era, and as his father had done with him and his brothers, he made sure that his sons, Adolph III (Ad), William (Bill), and Joseph (Joe) studied chemical engineering. All three sons were used to their father‟s strict disciplinarian approach, but Adolph Jr. was toughest on Bill. Unlike Adolph III and Joseph who had inherited similar personality traits from their father, Bill was considered an extrovert and independently-minded (Baum, 2000). All three sons were obedient and had learned the family business since they were young. In addition, the three sons worked together, shared the same office, raised their families together, expanded the family business as a team, and even obeyed what their father told them to wear to work (Sanchez, 2009). When Tivoli‟s brewery, a competitor of Coors in the local market was having problems competing against other brands, Adolph Jr. followed the family ethical approach to business established by his grandfather and instructed an employee, “don‟t prey on their draft account. Tivoli has a right to be in business” (Baum, 2000, p. 29). The Coors valued modesty and a culture of loyalty and simplicity. While paying kickbacks or a stocking allowance to retailers and wholesalers was common, the Coors family followed this practice because they believed that the most important factor was a quality product (Baum, 2000). The Coors‟ belief in modesty and simplicity pervaded throughout the family and the business. Even after he had taken over as Chairman of the company from his father, Adolph III was often seen working with laborers because the company insisted that all workers had equal responsibilities and lifelong loyalty to the company (Baum, 2000). Moreover, the family followed in the founder‟s belief that debt should be avoided and that earnings should be reinvested in the company. As the patriarch of the family business, Adolph Jr. lived in the mansion that his father built. However his three sons and their children lived modestly, with no sense of being wealthy. According to Baum (2000), “none of the brothers minded their humble lifestyle. They had all they needed. They were proud to live small. The Coors didn‟t work for money. They simply worked to make the best product possible” (Baum, 2000, p. 49). In the late 1950‟s, Bill came up with an idea to use a cold-filtering system to pasteurize beer, but the implementation of the technology required a large financial investment of several millions of dollars (Baum, 2000). Over daily lunches at Adolph Jr.‟s house, the family debated the advantages and disadvantages of such an investment. Decision-making in the Coors family was based on consensus, and “the company would go forward only when everyone was in agreement” (Baum, 2000, p. 50). Eventually, the family decided to take the risk and Bill‟s idea was implemented. Cold-filtering pasteurization provided Coors with a distinct competitive advantage over all competing beers and led to higher company growth (Baum, 2000; Banham, 1998). 6 In the early 1960‟s tragedy struck the family. Adolph III, who had been appointed president and heir to the family business, was kidnapped and killed (Sanchez, 2009; Baum, 2000; Banham, 1998). As the next oldest son, Bill Coors took over the leadership of the Adolph Coors Company. Baum (2000) noted that, “He [Bill] was next in line, and if anything was even more qualified than Ad to run the company. Unlike Ad, Bill was a brewer to his bones, possessed of his father‟s elegant nose and palate. He had both a gift for engineering and an education in it that Ad had lacked, and this would be essential to the task of growing the Golden brewery tenfold. Bill had everything it took to lead the Adolph Coors Company, except, of course, the name and the birthright. Bill might be the greatest brewer, the greatest engineer, and the greatest brewing executive in the country, but he could never be Adolph Coors III. His father took pains to make sure everybody knew it” (Baum, 2000, p. 64). The next in line for succession were Joseph Coors‟s sons, Joseph Coors Jr., Jeffrey, Peter, Grover and John. When Bill took over as Chairman and Joseph Coors as Vice Chairman of the Adolph Coors Company, the brewery was facing several challenges. First, the family business had not believed in business planning or the use of marketing and advertising to sell its products. Second, the brewery‟s business was a regional one restricted to the Western States. The Coors business had survived for almost 100 years on the strength of the quality and taste of one single beer. Because the beer was only found in the Western States and the fact that it was hard to get in other places of the United States, the beer developed a certain cult status becoming popular among movie stars, such as Paul Newman, and even sitting Presidents such as former President Gerald Ford (Baum, 2000; Banham, 1998). This “Coors mystique” plus the fact that the beer was brewed using Rocky Mountain spring water was one of the key factors that added to the brand and provided a competitive advantage to the business. Nonetheless, this successful niche was too narrow for the firm to pursue a national expansion strategy. Furthermore, the family was confronted by the Internal Revenue Service department with an inheritance-tax liability of $15 million. Bill and Joe did not have the money to settle this liability, which forced them to either borrow or go public to raise the money. Because of the family‟s long tradition of aversion to debt, Bill and Joe decided to go public. In order to maintain control, the company issued 10% Class B non-voting shares, while maintaining control of all voting Class A shares. The Initial Public Offering (IPO) was successful in raising $120 million, which in addition to covering the tax liability; it also provided the family with an opportunity to expand its operations geographically (Baum, 2000; Banham, 1998). However, going public also created a problem for Bill and Joe, who had always managed the company without any formal structure, and were unprepared to answer questions from investors about business plans, marketing and advertising plans, and/or strategies to deal with competitors. From the time fourth generation Peter Coors was a child, he learned not only the story of his family business background, but also about living humbly. Indeed, the 7 Coors “didn‟t need to flaunt their accomplishments; to carry the name Coors meant to possess not only personal wealth but the dedication and work ethic to make visionary dreams come true” (Baum, 2000, p. 129). Peter also followed in the footsteps of his father and uncle and studied industrial engineering at Cornell, but unlike his uncle Bill, Peter felt more comfortable with marketing than brewing and hoped to make it on his own outside the family business. After returning to Golden, Colorado, Peter enrolled at the University of Denver and obtained an M.B.A., the first member of the family with a graduate degree in Business. After graduation and just like what his uncle Bill had experienced, “Peter bowed to what he later called “the inevitable.” He crawled into the fermentation tank in 1970, the year his grandfather died. “I‟ll end up there anyway” he told Marilyn [wife] when he received his M.B.A. (Baum, 2000, p. 131). Peter brought a more formal business approach to the family business that included financial planning, market research, advertisement, and product development. However, Peter‟s greatest challenge and obstacles came from within the family, an uphill battle to change the older generation‟s management and business style (Baum, 2000). Furthermore in the 1970‟s, Peter was the first family member to recognize the impending consolidation trend in the American beer industry, the threat that it posed to a regional brewer such as Coors, and the importance of professional managers in growing the business. After more than three years of fighting the Board to persuade his father and uncle to introduce a light beer in order to compete with Miller, Peter convinced his older brother Jeffrey to develop one secretly. In 1977, both Joe and Bill capitulated to Peter after seeing and hearing the reviews of Coors new light beer (Baum, 2000). “Bill put up a brief fight about the brewing process Jeff had selected; he‟d have done it a different way entirely. But Jeff had brewed a winner without his gifted uncle, and it visibly stung Bill. He spent his theatrical ire over laboratory methods, insisted on a few minor changes, and then he declared the beer good- good enough to wear the Coors label” (Baum, 2000, p. 198). Bill Coors knew that the business had problems, but didn‟t know how to deal with them. He also saw Peter as someone who was more interested in selling beer than making it; and as someone who was steering away from the founder‟s vision that quality beer would sell itself, without advertising campaigns (Baum, 2000). In addition, Bill‟s engineering strengths were not enough to handle the increasing role of marketing and advertising in the beer industry. Baum (2000) noted “Bill would never admit as much to Peter, but he did- sort of- to reporters. „Making the best beer we can make is no longer enough‟, Bill had admitted” (Baum, 2000, p. 208). In 1978 at age 63, Bill was facing the prospect that the family business would eventually become a subsidiary of Miller or Anheuser-Busch. As much as he detested professional marketers, he realized that “Adolph and Adolph Jr. hadn‟t wanted to make malted milk… They‟d done it because they‟d had to. They‟d done it because if they hadn‟t, the Adolph Coors Company would have joined eight hundred other breweries killed by Prohibition. Bill could not place his 8 father‟s and grandfather‟s brewery at risk… he didn‟t like it, but he would have to adapt” (Baum, 2000, p. 212). In 1982, both Jeffrey and Peter were promoted into the company‟s executive office to share it with their uncle Bill, Chairman and CEO of the company, and their father Joe, President of the company. This move was seen as preparation for the eventual transfer of leadership to the fourth generation (Industry Week, 1982; Business Week, 1982). In 1987, Peter was named Vice-Chairman of Coors Brewing Co. He broke the family tradition and appointed Leo Kiely in 1993 as the first non-family President and CEO. In 2000, Peter Coors succeeded his uncle as Chairman of Coors Brewing Company, while Leo Kiely continued his role as President and CEO of Coors Brewing Company. In 2003 Coors reported revenue of $4.0 billion and a profit of close to $175 million, based on sales of 32.7 million barrels of beer and other malt beverages. However, Peter, Bill and Joe, feared that the business would eventually become a subsidiary of a larger company and lose its family business identity. Their long term strategy was survival of their family business in a changing and increasingly highly concentrated industry. The Beer Industry The American beer industry had been undergoing structural changes since the end of World War II. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) estimated that in 1946 there were about 404 independent breweries in the country, but by 1979, the number was down to 46 (Kramer, 1979). Moreover, the FTC report suggested that external forces, such as decreasing demand for beer; changes in consumer behavior from dark beers to lighter beers with less calories; diminishing profitability for brewers; increased use of marketing and advertising as well as increased competition among national and regional brewers; and the consolidation trend towards larger breweries were reshaping the whole industry (Kramer, 1979). The FTC report also had noted that industry leaders and national brewers Anheuser-Busch and Schlitz, as well as regional brewers Coors and Olympia had succeeded because these breweries were family businesses in which brewing is considered as “more than a business venture, i.e., a way of life” (Kramer, 1979). In 1978, the market share of the four largest brewers Anheuser-Busch, Schlitz, Miller and Pabst had grown from 25% to 60%, while Coors Brewing Company was in fifth place (The Economist, 1978). Competition among the top four brewers intensified after the tobacco company Philip Morris Companies acquired Miller Brewing Company. Philip Morris who had mastered the concept of market segmentation in the tobacco industry brought its expertise to turn Miller‟s business around, by introducing light-beers and switching Miller‟s corporate strategy from product-based to mass-marketing based (Baum, 2000). In 1969, Miller was ranked the seventh largest brewery, but by 1978, it had climbed to number three (The Economist, 1978). 9 The overturn of the anti-merger policy led to a series of acquisitions in the early 1980‟s. In 1980, industry leader Anheuser-Busch acquired a brewery from Schlitz, Stroh acquired both Schaefer in 1980 and Schlitz in 1982; and Pabst acquired Olympia Brewing Company in 1982 (Tremblay and Tremblay, 1988; Verespej, 1982). Most industry analysts agreed that the Coors family‟s philosophy was against acquiring other breweries, an assessment that was supported by Peter Coors who had refused to confirm or deny whether the company was interested in mergers (Verespej, 1982; Williams, 1981). While Peter Coors acknowledged that “the consolidation of the industry seems to be approaching its final stages,” Bill Coors suggested that “the door never has been closed to a merger” (Industry Week, 1982, p. 112). As the brewing industry in the American market consolidated into larger players, Anheuser-Busch initiated an international expansion strategy aimed at markets, such as Canada, Germany, and Japan (Business Week, 1981). In 1981, Anheuser-Busch and Labatt Brewing Company in Canada reached a licensing agreement for Labatt to brew and market Anheuser-Busch‟s best-selling beer, Budweiser, in the Canadian market. A few months after its introduction, Budweiser was able to capture between 7%-8% market share (Clifford, 1981). Labatt‟s licensing agreement with Anheuser-Busch represented a change of philosophy in the company because for the first time, a Canadian brewer chose to brew an American beer for the Canadian market instead of developing its own brand to compete against its rivals (Westell, 1981). Molson downplayed the partnership between Labatt and Anheuser-Busch. However, when Carling O‟Keefe Ltd., the third largest Canadian brewer, was rumored to have reached a licensing agreement with Miller to brew and launch Miller‟s best-selling brand, Miller Lite, in the Canadian market, Molson could no longer ignore the threat (Hunter, 1982). Both, Molson in Canada and Coors in the U.S., were in a surviving mode. They both had to start looking beyond their domestic markets for further growth opportunities. Both companies tried setting up a joint-venture, as well as a licensing agreement during the mid-1980. However, mergers between smaller regional brewers in the United States as well as international market expansion activities of larger brewers, Anheuser-Busch and Miller put additional pressure for both companies to look seriously for potential merger or joint-venture partners, given that North America was becoming one single market (Clifford, 1989). The Merger between Equals The merger between the two family businesses- Molson and Coors- was a matter of survival in the face of consolidation and globalization trends. According to Eric Molson, it was „strategically compelling merger‟ that would make the new company the fifth largest brewer in the world at the time, after Anheuser-Busch of the United States, SABMiller of South Africa, Interbrew Group of Belgium, and 10 Heineken of the Netherlands (Financial Times, 2004a). Eric Molson provided additional arguments for the merger: “First, both companies have complementary strengths, a heritage and a commitment to the brewing business and a common vision for future growth. Second, because of a variety of factors, no other partnership offers as much at this time as the one with Coors. Third, merging these two companies provide shareholders with a solid prospect of sustained returns in the short, medium, and long term. Finally, the merged company has all the potential to move to the next level and become a powerful industry consolidator” (Brent and Tomesco, 2005, p. FP5). While the short term focus of the new company would be in merging the two firms‟ organizational structures and operations, industry analysts expected that SABMiller‟s American brewing operations, as well as Femsa, Mexico‟s second largest brewer were potential acquisition targets (Brent and Tomesco, 2005). Even though there had been some criticism about the Molson-Coors‟ merger proposal, Eric Molson argued that the deal would also create savings to the combined company and that Fairvest, a Toronto governance advocate had supported the deal, though reluctantly because the merged company would report a single-digit profit gain (Westell, 2005). However, Burgundy Asset Management, a minority shareholder had opposed the deal because “Molson was almost four times as profitable as Coors in terms of profit per unit of beer produced” (Westell, 2005, p. 16). Other analysts had also raised questions about which family would be in control, how would the family handle shareholders‟ structure given the presence of Class A and B shares, and how would an equal merger work, in light of the potential for deadlock (Marotte, 2004). There was also an issue of unclear succession at Coors because Peter Coors had announced his intentions to run for a seat in the U.S. senate and if he were to win, he would have had to step down as Chairman of the family business (McKenna, 2004). In addition, analysts were suspicious that “this proposed merger appears to be more about maintaining family business empires than maximizing shareholder value” (Marotte, 2004, p. B6). Nonetheless, the combined company would have a market capitalization of almost $6 billion, $2.7 billion from Coors and $3.2 billion from Molson, though still trailing AnheuserBusch Cos. Inc., with a market capitalization of $24.5 billion and Belgium‟s Interbrew, with a market capitalization of $12 billion (McKenna, 2004; Marotte, 2004). The merger plan also ignited a family feud over the advantages of the merger between Deputy Chairman, Ian Molson and Chairman, Eric Molson (Brent and Silcoff, 2004). The family feud may have started when Ian tried to succeed Eric as Chairman, a move that was opposed by Eric (Brent and Silcoff, 2004; The Economist, 2004; Reguly, 2004). Furthermore, given the consolidation in the global brewing industry towards larger players, analysts had predicted a possible Heineken-Molson merger. However, Heineken executives had stated that they “didn‟t see the rationale or the value creation behind Heineken buying Molson” (Brent and Silcoff, 2004, p. F1). There was already a relationship between these 11 two brewers because in Canada, Molson distributes Heineken beer (Silcoff, 2003). Nevertheless, while the Molson Board was evaluating the Molson-Coors proposal, Ian looked into preparing a competing bid with the help of Heineken, which is controlled by the Heineken family, to buy out Molson for $4 billion (The Economist, 2004). Although Eric Molson was the champion behind the Coors merger, Coors was hesitant about Ian‟s alternate bid. It had threatened to break the marketing agreement that existed between Molson and Coors if investors chose someone else as a merger partner for Molson. However, Coors would not have legal grounds as the agreement was in effect as long as any Molson family member was in control (Flavelle, 2004). To complicate the matter further Eric had a prior agreement with Ian to ensure that the family could block any potential hostile takeover of Molson, but this agreement also gave Ian a veto to the Coors deal (McArthur, 2004b). Eric and his brother Stephen controlled 44.69% of the Class B voting shares through a holding company, Pentland Securities. In addition, the estate of THP Molson, Eric‟s father, also owned 10.76% of the voting shares, while Ian with 10.28% was expected to vote against the deal (McArthur, 2004b). Five days before the merger announcement, Ian tried to find new partners, such as SABMiller or financier Onex Corp, to submit a counter bid at $40/share, but was not able to do it (Simon, 2004a; Flavelle, 2004). Shortly after, Ian resigned from the Board (The Economist, 2004). He called the deal “a bad transaction and the status quo a better option” (Politi, 2004, p. 19). Outside investors, were also not fully behind the merger because no premium price was set on the Molson stock price, which was listed at $37/share. Furthermore, industry analysts criticized the deal as “designed primarily to entrench the Molson and Coors families in their long-established businesses” (Simon, 2004, p. 25). In addition for Molson, a strategic merger with Coors would stop Heineken from potentially targeting Coors (Brent and Silcoff, 2004). Some analysts also viewed the deal as one where Eric would continue to wield control of the family business because he would become Chairman of the combined company, which would provide a succession path not only for Eric‟s son Andrew Molson, but also for Peter‟s daughter Melissa Coors. Both Andrew and Melissa would become directors in the new company (McArthur, 2004a). It would also be the first time for a member of the seventh-generation Molson family and fifthgeneration Coors family to have a seat in their respective brewery‟s board (McArthur, 2004a). Seventh generation Andrew Molson commented that “two families that have been in the brewing business for a long time are getting together to continue to be in the brewing business for a long time, but this time together- and to get bigger together- acting in the interests of all shareholders and stakeholders. I don‟t think it [the appointment to the board] means that I would be chairman. My 12 brother Geoff is extremely competent, understands the beer business and I hope that one day he would be on the board with me” (McArthur, 2004a, p. B1). Luc Beauregard, a Molson director and CEO of a public relations firm that employs Andrew Molson, suggested that Andrew‟s expertise in corporate governance would be an advantage for the new company, and noted that “Andrew is a bit like his dad, in the sense that he‟s very intense, but very discreet- not a flashy person. Choosing between two kids is very difficult for any parent. Andrew‟s the oldest and has the corporate preparation. Geoff has more hands-on experience of the company” (McArthur, 2004a, p. B1). Molson also gave directors and employees, who were holding options on Molson non-voting shares, the right to vote on the merger, which required approval of two thirds of the voting and non-voting shareholders (Simon, 2004a). However, the Financial Times criticized the action to give share option holders, who had not paid for their shares, the right to vote because this diluted the rights of full shareholders (Financial Times, 2004b). According to a Molson‟s spokesperson, giving option holders a vote was not unusual in Canada and that “some companies do and some do not” (Simon, 2004a, p. 25). In November of 2004, Molson offered investors a raise in dividends from $3 to $3.26 to appease institutional investors‟ claim that there was little premium on the prevailing share price after the merger. The Molson family, who held 55% of the voting shares, also waived its right to receive the dividend (Simon, 2004b). One week before the scheduled shareholders‟ vote, SABMiller proposed that if the Coors merger is turned down, they would be interested in making a proposal that would be of benefit to Molson shareholders. However, Eric who had veto power stated that “this company is not for sale and the merger of equals with Coors is the only option on the table on January 19” (Politi, 2005). Eric‟s veto power came from his 55.4% control of the voting shares partly through a family trust (Financial Times, 2004a). However, both Molson and Coors were small brewers compared to AnheuserBusch, Interbrew, or SABMiller. Reid (2004) suggested that the intangible ingredient of the merger was brewer‟s pride. According to Reid, “Brewer‟s pride is a pride in the craft that goes beyond the business aspects of brewing. This pride is not something that the moneychangers understand, so it is easily dismissed. It is something that usually accumulates over generations, although the true artisans acquire it early. Eric Molson has this pride, while at Coors it may be waning. Bill Coors has left the building, and Pete may be headed for Washington, D.C. [Peter Coors had announced his intentions to run for the U.S. senate], so at this juncture, Molson can help relight the candle at Coors. For truly these families do not want to sell their companies, or submit to a European overlord. They want some aspect of the family breweries to survive and thrive independently into this new century. These families speak the same language, the language of beer and brewers. Brewer‟s pride has taken many a family company over the precipice, 13 but in this case it could help Molson/Coors ascend to the next plateau” (Reid, 2004). Under the merger arrangement, Molson shareholders held 55% equity stake in the new company, while Coors shareholders held 45%. Moreover, Eric Molson‟s shares were combined with the Coors family shares into a trust that controls 62% of the voting shares in the new company (Silcoff, 2004b). Commenting on the merger, former Coors Chairman, Bill Coors noted that in the “long range, I don‟t think it‟s practical to think a brewery like us with the modest market share we have in this country can continue like we have. If we don‟t expand our operations and become global, we aren‟t going to make it. That‟s basically what‟s behind this thing” (Silcoff, 2005, p. FP1). Furthermore, Bill Coors who was a strong supporter of the deal added that, “history shows that when an industry starts consolidating, you either consolidate, you get consolidated, or you perish” (Brent, 2005a, p. FP1). Coors Chairman, Peter Coors added that the merger represents a “combination of two families, both of whom want to stay in the beer business and want to stay in control of their destinies in the beer business. The structure that we have been able to achieve through this merger allows both the Molson family and the Coors family to have a significant control on an ongoing basis in our destiny. We have to learn to work together but we have been working together since 1985” (Brent, 2005a, p. FP1). Although it was expected that Coors shareholders would readily approve the merger, Molson shareholders argued that the deal was in effect a takeover of Molson by Coors (Brent, 2005a). Coors CEO Leo Kiely, the designated CEO of the new company answered that “we were concerned about the optics of that from the beginning. I really think the place to look is at the governance of the company. This is just clearly a merger of equals. You look at the balance of the board, the balance of the voting trust, this is a flat-out merger.” In regard to the criticism that the deal was for the two families to maintain control, Kiely replied that “it‟s huge asset in the beer community. It‟s stability. It‟s trust. You go around talking to beer guys and you have got this family overlay and it is very attractive for partnerships. They like talking to families. They like families that are committed generationally. So it is sort of ironic the split you‟ve got with the investment community” (Brent, 2005a, p. FP1). This „merger of equals‟ was finalized in February of 2005, with Eric remaining as Chairman, Peter H. Coors as Vice Chairman, and W. Leo Kiely III, CEO of Coors as the new CEO of Molson Coors Brewing Co. (Molson Coors, 2004). The Board of Directors was reconstituted with two members of each family sitting at the new Board, Eric and his son Andrew T. Molson, as well as Peter H. Coors and his daughter Melissa E. Coors. In addition two senior executives, Daniel O‟Neill and W. Leo Kiely III sat on the Board plus nine independent directors, including Dr. Francisco Bellini, Chairman and CEO of Neurochem Inc., John E. Cleghorn, Chairman of the Board of SNC-Lavalin, and David P. O‟Brien, Chairman of 14 EnCana Corporation, and Dr. Albert C. Yates, President Emeritus Colorado State University (Molson Coors, 2004). At the post-merger press conference with Peter and Bill Coors, Peter commented about Eric and the Molson family, “we‟re very close. We have known Eric Molson through technical meetings and industry meetings for years and years and years and I think, Uncle Bill, you knew Eric‟s father. We‟ve known each other for a long time, we respect them as brewers, they respect us as brewers, and we respect each other from a marketing perspective. You can‟t put two people together and expect perfect harmony but this is as harmonic as I think you can possibly get putting two companies together” (Brent, 2005b, p. FP1). Bill re-emphasized the point that survival was also a driving force for both families and noted that, “when I went to work for this company in 1939, there were about 750 family-owned and family-operated breweries. There are only two of them in this country left really of any consequence. So survival has been our long-term strategy” (Brent, 2005b, p. FP1). In its first Annual Report, Molson Coors Brewing Company reported a whopping sales of $7.4 billion, net sales of $5.5 billion (after excise taxes), net income of $134.9 million, and total assets of $11.8 billion (Molson Coors, 2005). The Molson-Coors company is unique, the new company‟s Annual Report, noted, “We are one of the world‟s largest brewers, managed with the active involvement of two founding families that represent a combined 350 years of brewing excellence” (Molson Coors, 2005). The new company‟s vision was for Molson Coors Brewing Co. to become „the top-performing global brewer, winning through inspired employees and great brands‟ (Molson Coors, 2005). Two years after the merger, Molson Coors reported in 2006 record sales of 42.1 million barrels of beer, gross sales of $7.9 billion, net sales of $5.8 billion, and a net income of $361 million (Molson Coors, 2006). Molson Coors was also on track to achieving the goals that were set out as part of the benefits for the merger, including the anticipated operational efficiencies. In their address to shareholders, Eric Molson and Peter Coors stated that the merger of equals was working: “The fact that we have endured while so many other family brewers have left the business is no accident. First of all we are passionate about our beer. We are proud of the standards of brewing excellence set by the generations who went before us. Those standards are a gift from them to us, something to be upheld for the generations that follow. Second, we have endured because we have a strong sense of who we are and the principles we believe in, such as dealing with each other and those around us with honesty, compassion, and integrity” (Molson Coors, 2006). In 2007, sales for Molson Coors reached another record of $8.3 billion and net income of $497 million (Molson Coors, 2007). Also in October 2007, SABMiller 15 and Molson Coors agreed to a joint-venture that combined their operations in the United States and Puerto Rico to create a more effective competitor to AnheuserBusch (Sorkin and de la Merced, 2008). The Miller-Coors venture did not cover Molson Coors or SABMiller operations outside the United States; however, it gives the new company 30% of the domestic American market, behind market leader Anheuser-Busch (Pitts, 2008). Sales and net income for Molson Coors in 2008 dropped to $6.6 billion and $388 million, respectively, a reflection of the continuing competitiveness in the global beer industry, as well as uncertainties in the global economy (Molson Coors, 2008). In September, 2008, Peter Swinburn, the newly-appointed CEO of Molson Coors Brewing Co., commented that the Molson Coors merger in 2005 has been successful as shareholder value improved by 90% in the three years following the merger (Pitts, 2008). In November 2008, Molson Coors bought 5% equity in Foster‟s Group, with the intention to acquire their brewing operations (Speedy, 2008). The trend towards consolidation among brewers has not abated and further consolidation was expected, as brewers fight for survival in an increasingly concentrated global industry. In 2008, Inbev (a result of a merger between Interbrew of Belgium and AmBev of Brazil) announced its intention for a hostile takeover of Anheuser-Busch, the world‟s second largest brewer (Jones, 2008). Peter Swinburn noted that “what is attractive about the Molson Coors business now is it is truly international. We operate in 30 countries and Coors Light, in particular, is doing extremely well worldwide. It‟s good for Molson Coors and what is good for Molson Coors is good for Canada” (Pitts, 2008). At the May 13, 2009 Molson Coors annual meeting of stockholders, Eric Molson who had been replaced as Chairman by Peter Coors in December 2008, retired from the board and was replaced by his youngest son, Geoff (Molson Coors Notice, 2009). Meanwhile, Andrew Molson replaced Peter Coors as the Vice Chairman of the Board. The smooth change of leadership from the Molson to the Coors three years after the merger reflects the harmony that exists between these two families and the success of the merger. 16 Exhibit 1. A Simplified Family Tree Reflecting Succession and Key Family Members Involved in the Family Business (shaded boxes). 17 Exhibit 2. A simplified Family Tree Reflecting Succession and Family members Involved in the Coors Family Business (shaded boxes). 18 References Alden E. (1999). O‟Neill to Head Molson‟s North American Brewing. Financial Times (London, UK), March 2, p. 12. Banham, R. (1998). Coors: A Rocky Mountain Legend. Lyme, Connecticut: Greenwich Publishing Group, Inc. Baum, D. (2000). Citizen Coors: An American Dynasty. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers Inc. Brent, P. (2005a). Molson Coors rules out merger with SABMiller: „It‟s too risky,‟ CEO says. National Post’s Financial Post, Feb. 2, p. FP1. Brent, P. (2005b). Culture shock may be brewing: Merger just first step for Coors mountain men and Molsons. National Post’s Financial Post, Feb. 5, p. FP1. Brent, P. and Silcoff, S. (2004). Molson takes over Coors: Critics say merger plans driven more by personal- not shareholder- interests. National Post’s Financial Post, July 21, p. F1. Brent, P. and Tomesco, F. (2005). Merger Turns prey into predators: Now fifth largest brewer: Is Mexico‟s Femsa in company‟s sights? National Post’s Financial Post, Jan. 29, p. FP5. Business Week (1982). “The youth movement in Coors management,” May 24, p. 50. Business Week (1981). “Anheuser Tries Light Beers Again,” June 29, p. 136. Clifford, E. (1989). Breweries need allies in single beer market. The Globe and Mail, Sep. 27. Clifford, E. (1981). Labatts gets dream product in its new Budweiser brand. The Globe and Mail, April 21. Coors (2003). Coors Brewing Company 2003 Annual Report. Deacon, J. (2001). Faded Glory. Maclean’s, 114(6), p.38-42. Denison, M. (1955). The Barley and the Stream: The Molson Story. Toronto, ON: McClelland & Stewart. Financial Times (2004a). “Family Values,” London (UK), July 23, p. 20. Financial Times (2004b). “The Molson,” London (UK), Sep. 21, p. 16. 19 Flavelle, D. (2004). Molson discloses key marketing agreement. The Toronto Star, Oct. 7, p. CO1. Hunter, D. (2001). Molson: The Birth of a Business Empire. Toronto, ON: Penguin Books Canada. Hunter, N. (1982). Brewers to woo Canadian drinkers with U.S. brands. The Globe and Mail, April 14. Industry Week (1982). “Next To Merge? Latest battle pivot around Pabst,” June 14, p. 112. Jones, R. L. (2008). Our plan is to look for any smart acquisitions and mergers. The Globe and Mail, Aug. 27, p. B3. Kramer, L. (1979). FTC sees growing brewery competition. The Washington Post, p. F1. Library and Archives Canada. Molson Archives, MG 28, III 57, Vol. 373-374. Marotte, B. (2004). Questions mount over marriage of brewers. The Globe and Mail, July 24, p. B6. McArthur, K. (2005). Merger has double the family factor; the new head of Molson-Coors has two dynasties to contend with. The Globe and Mail, Feb. 8, p. B5. McArthur, K. (2004a). Molson, Coors scions slated for new Board. The Globe and Mail, Aug. 4, p. B1. McArthur, K. (2004b). Battle over Molson could end in a draw. The Globe and Mail, Oct. 11, p. B1. McKenna, B. (2004). Family firms share similar history and modern woes; beer companies controlled by founders‟ descendents; both face marketing wars. The Globe and Mail, July 20, p. B3. Molson. (2003). Molson 2003 Annual Report: Continuing to Deliver. Molson Coors. (2008). Molson Coors Brewing Company 2008 Annual Report. Molson Coors. (2007). Molson Coors Brewing Company 2007 Annual Report. Molson Coors. (2006). Molson Coors Brewing Company 2006 Annual Report. 20 Molson Coors. (2005). Molson Coors Brewing Company 2005 Annual Report. Molson Coors. (2004). Adolph Coors Company 2004 Annual Report. Molson Coors Notice (2009). Annual Meeting of Stockholders, May 13. Molson, K. (2006). Hartland De Montarville Molson: Man of Honour. Willowdale, ON: Firefly Books. Molson, K. (2001). The Molsons: Their Lives and Times 1780-2000. Willowdale, ON: Firefly Books. Pitts, G. (2008). A new beer baron, and his take on liquid assets. The Globe and Mail, Sep. 29, p. B1. Politi, J. (2005). Molson Interests S African Brewer SABMiller. Financial Times (London, UK), Jan 13, p. 18. Politi, J. (2004). Coors and Molson set for Dollars 6Bbn Merger. Financial Times, London (UK), July 22, p. 19. Reid, P.V.K. (2004). The Coors/Molson merger: A good deal? Modern Brewery Age, Sep. 13. Reguly, E. (2004). It‟s time for Eric Molson to realize his chairmanship has gone flat. The Globe and Mail, June 22, p. B2. Sanchez, R. (2009). Anatomy of a murder. 5280.com. Silcoff, S. (2005). Yes or No: Decision day. National Post’s Financial Post, Jan. 27, p. FP1. Silcoff, S. (2004a). End of Canadian brewer to break „link to our past:‟ Karen Molson: Great-great-great-great granddaughter of founder speaks out. National Post’s Financial Post, July 22, p. FP1. Silcoff, S. (2004b). When Onex rang: Ian was ready for action: Cousins Eric and Ian Molson both want the brewer to grow- but not in the same way. National Post’s Financial Post, July 24, p. F1. Silcoff, S. (2003). Molson not for sale: CEO: blasts media coverage. National Post’s Financial Post, Sep. 18, p. FP01. Simon, B. (2004a). Molson gives option holders a say. Financial Times, London (UK), Sep. 20, p. 25. 21 Simon, B. (2004b). Molson Offers Special Dividend in Merger Move. Financial Times (London (UK), Nov., 6, p. 8. Speedy, B. (2008). Takeover brewing as Molson Coors build 5pc stake in Foster‟s. The Australian, Nov. 7, p. 19. Sorkin, A.R. and de la Merced, M.J. (2008). Inbev said to consider bid for Anheuser-Busch. The New York Times, May 24, p. 2. The Economist (2004). “Business: Family Brew; Mergers,” July 31, p. 58. The Economist (1978). “A Tasteless Tale”, Jan. 7th, p. 33. Tremblay, V. J. and Tremblay, C. H. (1988). The determinants of horizontal acquisitions: Evidence from the US brewing industry. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 37(1), pp. 21-45. Verespej, M. A. (1982). Third place at stake; beer industry brews another battle. Industry Week, May 17, p. 78. Weber, J. (1997). Back to the Future at Molson; Its Bid to be a Pure Play in Brewing isn‟t Impressing Stockholders. Business Week, Sept., 29, p. 28. Westell, D. (2005). Molson family member opposes Coors merger. Financial Times, London (UK), Jan 12, p. 16. Westell, D. (1981). Budweiser introduced. The Globe and Mail, March 18. Williams, W. (1981). Pressure on small brewers. The New York Times, Aug. 8, section 2, p. 33. Woods, S. E., Jr. (1983). The Molson Saga: 1763-1983. Toronto, ON: Doubleday Canada. 22