Producing and Consuming Narratives The value of fairtrade coffee

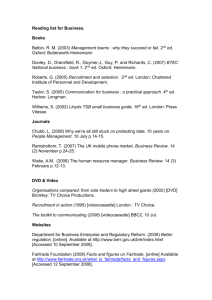

advertisement