BEST PRACTICES for Serving Court Involved Youth with Learning

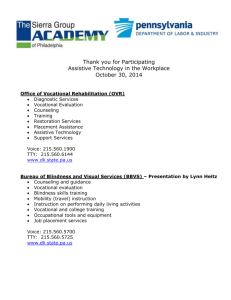

advertisement