Document

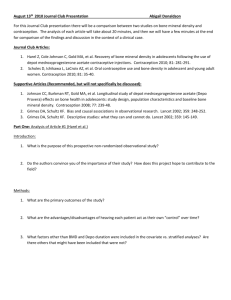

advertisement

Oral contraceptive use in perimenopause Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD Jacksonville, Florida Perimenopause represents a transition period lasting about 5 years before the permanent cessation of spontaneous menses. During this transition, the emphasis of clinical care changes. Although women still need effective contraception during perimenopause, issues including loss of bone mineral density, menstrual cycle changes, and vasomotor instability also need to be addressed. Hormone replacement therapy is not the first-line treatment for women with symptomatic perimenopause because hormone replacement therapy neither suppresses ovulation nor provides contraception; also, it will not prevent and in fact may aggravate unpredictable perimenopausal bleeding. Oral contraceptives offer many benefits for healthy, nonsmoking, perimenopausal women. Oral contraceptive use by women in their 40s has been found to decrease the risk of postmenopausal hip fractures and regularize menses in women with dysfunctional uterine bleeding, reducing the need for surgical intervention for benign menstrual conditions. Use of oral contraceptives also can reduce long-term risk of endometrial and ovarian cancers. There is also good evidence that oral contraceptives relieve vasomotor symptoms in perimenopausal women. Oral contraceptives can be viewed as a strategy not only to improve perimenopausal symptoms, provide effective contraception, and reduce some long-term health risks, but also to enhance the quality of life for perimenopausal women. (Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;185:S32-7.) Key words: Oral contraception, bone mineral density, menstrual changes, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, vasomotor instability, triphasic norgestimate/35 µg ethinyl estradiol, monophasic norethindrone acetate/20 µg ethinyl estradiol Perimenopause constitutes a transition period characterized by unpredictability; 1 month does not predict the next in terms of the menstrual cycle or other symptoms. Overall, perimenopause occurs about 5 years before the permanent cessation of spontaneous menses, so clinicians can anticipate that patients in their mid 40s will begin to experience manifestations of this transition.1,2 Although the cycle length begins to shorten, the potential for ovulation and pregnancy is preserved for a number of years.1,3,4 Therefore perimenopausal women still need effective contraception. Other issues that must be addressed in this age group are menstrual changes, including dysfunctional uterine bleeding; vasomotor instability; and prevention of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and gynecologic cancers. Oral contraceptive use in perimenopause The effectiveness of oral contraceptives (OCs) is high in perimenopausal women.5 Although perimenopausal From the Gynecology, Menopause and Bone Density Services, Medicus Diagnostic Center, Department of Obstetric and Gynecology, University of Florida Health Science Center. Reprint requests: Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Florida Health Science Center, 653-1 W 8th St, Jacksonville, FL 32209. Copyright © 2001 by Mosby, Inc. 0002-9378/2001 $35.00 + 0 6/0/116525 doi:10.1067/mob.2001.116525 S32 women tend to be less fertile6 and are also better pill-takers than are younger women, they are still at risk for unintended pregnancy and therefore require contraception. Yet only 4% of women in the United States aged 45 to 50 years reported in a recent survey that they were using the pill.7 The dominant method used by older women is sterilization, which has a higher long-term rate of failure than was believed previously.8 Many older reproductive-age women are reluctant to use OCs because they fear serious health risks such as cancer and cardiovascular disease.9-11 Another concern, not only among teenagers but also among perimenopausal women, is weight gain. Perimenopausal women are not likely to use OCs successfully unless clinicians address such fears and educate patients about the many benefits of continuing or initiating OC use during the perimenopause. Contraception. Many perimenopausal women fail to appreciate the continuing need for effective contraception, yet statistics suggest that 80% of women between the ages of 40 and 44 can conceive.12 Consequently, older women have a high rate of unintended pregnancy. Data from the National Survey of Family Growth show that 51% of pregnancies that occurred among women aged 40 and older during 1994 were unintended; 65% of these unintended pregnancies ended in abortion.13 Because lack of cycle predictability is the rule in this age group and unanticipated ovulation may occur, contraception must be practiced if pregnancy is not desired.1 Kaunitz S33 Volume 185, Number 2 Am J Obstet Gynecol Fig 1. Incidence of breakthrough bleeding or spotting at each cycle. Asterisk, Significantly less breakthrough bleeding/spotting at each cycle with triphasic norgestimate/35 µg ethinyl estradiol versus norethindrone acetate/20 µg ethinyl estradiol (P < .001). NGM, Norgestimate; EE, ethinyl estradiol; NETA, norethindrone acetate. Adapted from Sulak P, Lippman J, Siu C, Massaro J, Godwin A. Clinical comparison of triphasic norgestimate/35 µg ethinyl estradiol and monophasic norethidrone acetate/20 µg ethinyl estradiol: cycle control, lipid effects, and user satisfaction. Contraception 1999; 59:161-6. Copyright 1999, with permission from Elsevier Science. Bone mineral density and prevention of postmenopausal osteoporotic fractures. Women attain peak bone mineral density between ages 20 and 40, after which age-associated losses are about 1% per year.14 Bone loss accelerates during perimenopause and menopause,14, 15 and annual losses of 3% to 5% may occur in the 5 years after the onset of menopause.14 One well-established risk factor for decreased bone mineral density is the existence of a hypoestrogenic state, such as anorexia nervosa,14 exercise-induced amenorrhea,14 early oophorectomy,14 premature ovarian failure,14 hyperprolactinemia,14 chemotherapy or radiation therapy,16,17 and gonadal dysgenesis.18 By taking OCs, a 45-year-old woman can better maintain her bone mineral density. Prospective studies of perimenopausal women have found that OC users can preserve bone mineral density, whereas bone loss has been observed in nonusers.19,20 These findings suggest that premenopausal use of OCs can prevent the accelerated bone turnover and reverse the decrease in bone mineral density that accompany declining ovarian function.20 Moreover, the longer the duration of exposure to OCs, the greater is the positive effect on bone mineral density.21-24 Recently, a large case-control study in Sweden showed that women who took OCs in their 40s decreased their risk of postmenopausal hip fractures by 30% compared with those who had never used OCs (Table I).25 Menstrual cycle changes. Bleeding changes represent one of the most common reasons for which perimenopausal women consult a clinician. Such changes Table I. Decreased hip fracture risk with oral contraceptive use Age at oral contraceptive use Multivariate any oral contraceptive Never used <30 y 30-39 y ≥40 y 1.0 (referent) 1.3 (0.8-2.1) 0.8 (0.6-1.2) 0.7 (0.5-0.9) Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) ≥50 µg ethinyl estradiol oral contraceptive 1.0 (referent) 1.1 (0.6-2.0) 0.8 (0.5-1.1) 0.6 (0.4-0.9) Adapted with permission from Michäelsson K, Baron JA, Farahmand BY, Persson I, Ljunghall S. Oral-contraceptive use and risk of hip fracture: a case-control study. Lancet 1999; 353:1481-4. ©1999 by The Lancet Ltd. raise concerns about the presence of cancer or other underlying disease and cause patient anxiety. Erratic bleeding in perimenopausal women reflects the less predictable ovulatory pattern characteristic of this transition. Usually the cycle length shortens by 2 to 7 days, although longer cycles or irregular menses are possible.6 There are also changes in the quality of bleeding (heavier cycles initially, then lighter flow) and spotting before menses.6 This dysfunctional uterine bleeding not only is annoying for women but also can put them at increased risk for endometrial hyperplasia.2 For decades OCs have been used to control uterine bleeding and regularize menses. Now there are data showing that use of a specific OC formulation regularizes menses in women complaining of dysfunctional uterine bleeding.26 In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi- S34 Kaunitz August 2001 Am J Obstet Gynecol Figure available in print only Fig 2. Oral contraceptives decrease number and severity of hot flashes in perimenopausal women. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-cycle trial. EE, Ethinyl estradiol; NETA, norethindrone acetate. Adapted with permission from Casper RF, Dodin S, Reid RL, and Study Investigators. The effect of 20 µg ethinyl estradiol/1mg norethidrone acetate (Minestrin), a low-dose oral contraceptive, on vaginal bleeding patterns, hot flashes, and quality of life in symptomatic perimenopausal women. Menopause 1997; 4:139-47. Table II. Impact of low-dose oral contraceptives on lipid profiles in premenopausal women: randomized, open-label, 6-cycle trial in women aged 18-50 years; lipid changes baseline to final visit Median % change Lipid High-density lipoprotein– cholesterol HDL2 Apo A-1 Triphasic norgestimate/ 35 µg ethinyl estradiol Norethindrone estradiol acetate/ 20 µg ethinyl estradiol 4.5%* –4% 25%† 17.9%* 13.3% 9.8% Adapted from Sulak P, Lippman J, Siu C, Massaro J, Godwin A. Clinical comparison of triphasic norgestimate/35 µg ethinyl estradiol and monophasic norethidrone acetate/20 µg ethinyl estradiol: cycle control, lipid effects, and user satisfaction. Contraception 1999; 59:161-6. Copyright 1999, with permission from Elsevier Science. HDL2, High-density lipoprotein–variant 2. *P < .001. †P < .004. center trial, 201 women with metrorrhagic, menometrorrhagic, oligomenorrheic, or polymenorrheic dysfunctional uterine bleeding were randomized to receive an OC (triphasic norgestimate/35 µg ethinyl estradiol) or placebo for 3 cycles. For each subtype of dysfunctional uterine bleeding, improvement was noted for subjects treated with OCs. Overall, significantly fewer women receiving OC than those receiving placebo reported abnormal bleeding (P < .001). Regarding the effect of dysfunctional uterine bleeding on quality of life, the women who received OCs also had greater improvement from baseline in physical function (eg, self-care, walking, lifting, bending, exercise) than subjects given placebo. Data from a 6-cycle randomized clinical trial in premenopausal women show that rates of breakthrough bleeding with this 35-µg estrogen formulation are one third lower than with a 20-µg estrogen formulation (monophasic norethindrone acetate/20 µg ethinyl estradiol) (Fig 1).27 These observations provide high-quality evidence that the 35-µg estrogen OC formulated with triphasic norgestimate represents a sensible choice for women diagnosed with irregular bleeding, including perimenopausal women. In addition to the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding, OCs represent an appropriate first-line therapy for primary dysmenorrhea and heavy flow/menorrhagia (including women with uterine fibroids), although these indications for use are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration.28-30 Rates of hysterectomy for benign menstrual conditions, particularly fibroids and dysfunctional uterine bleeding, peak among women in their 40s.31 Thus OCs can be viewed as a strategy not only to improve perimenopausal symptoms, provide effective contraception, and diminish the risk of fractures and gynecologic cancers, but also as a way to reduce the need for gynecologic surgery for benign menstrual conditions. Lipid profiles in women using oral contraceptives. A randomized study of women between the ages of 18 and 50 showed that the triphasic norgestimate/35-µg ethinyl Volume 185, Number 2 Am J Obstet Gynecol estradiol OC produced considerably more desirable lipoprotein changes than the monophasic norethindrone acetate/20-µg ethinyl estradiol OC (Table II).27 The 35-µg ethinyl estradiol OC had significantly (P ≤ .001) greater beneficial effects on high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein–variant 2, and apoprotein A-1 than the 20-µg ethinyl estradiol OC. Whether these findings are clinically relevant to the average perimenopausal woman is not known; however, for patients with a history of smoking or dyslipidemia and those with a family history of premature coronary artery disease, selection of an OC formulation that provides a more favorable lipoprotein profile would appear prudent. Vasomotor symptoms. Approximately 85% of perimenopausal women experience symptoms of vasomotor instability (ie, hot flashes, night sweats, sleep disturbances).6 The intensity, duration, and frequency of these symptoms are highly variable; some women experience one or two hot flashes daily whereas others may have 40 per day.6 There is evidence showing that OCs relieve vasomotor symptoms in perimenopausal women.19,32 In a 3-year, prospective cohort study comparing 100 perimenopausal women treated with a triphasic OC (ethinyl estradiol 30/40/30 µg/levonorgestrel 0.05/0.075/0.125 mg) with a similar number of age-matched untreated women, 90% of the OC users obtained complete relief of vasomotor symptoms after 2 months’ use, and the remaining 10% responded after 3 months.19 By contrast, 60% of untreated women had no improvement in vasomotor symptoms during these 3-month observations. The failure to use blinding or a placebo group, however, limits the credibility of this study’s findings. A placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized, parallel group study in 132 perimenopausal women showed that a low-dose, monophasic OC (20 µg ethinyl estradiol/norethindrone acetate 1 mg) also decreased hot flashes.32 Among the 65% of subjects who experienced at least one hot flash daily (38 OC, 36 placebo), OC users experienced approximately 50% fewer hot flashes over the 6-month study period than placebo users (Fig 2). Similarly, the mean severity (rank: mild = 1, moderate = 2, severe = 3) of hot flashes among OC users was half that of placebo users; mean severity scores were 66.9 and 131.2, respectively. However, these differences were not statistically significant in this small clinical trial. Evaluation and management of perimenopausal women Prevention of cardiovascular disease. Clinical experience suggests that the perimenopausal woman is much more receptive to recognizing her own mortality than are teenage girls, many of whom consider themselves invulnerable. Older women recognize that cardiovascular risk reduction is important; they will pay closer attention to lifestyle issues such as smoking cessation, diet, exercise, Kaunitz S35 Table III. Benefits of oral contraceptive use in perimenopausal women Effective contraception (if needed) Treatment of irregular menses/dysfunctional uterine bleeding, menorrhagia, and/or dysmenorrhea Reduction in vasomotor symptoms High bone density/fewer fractures Prevention of ovarian and endometrial cancers Treatment of acne and weight control to achieve reductions in cardiovascular risk. The guidelines of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists indicate that regular cholesterol screening every 5 years is appropriate in this age group.33 Prevention of bone loss. As with cardiovascular disease, lifestyle issues are key factors in maintaining good bone mineral density before menopause and preventing postmenopausal fractures. Adequate dietary intake of calcium and vitamin D, avoidance of excess alcohol or caffeine, smoking cessation, and weight-bearing exercise all represent important strategies to prevent bone loss in perimenopausal women.33,34 Selective use of bone density testing, on the basis of the presence of risk factors, is recommended. As indicated earlier, OCs can provide a powerful tool for maintaining or even increasing bone mineral density in women in their 40s and for preventing fractures later in life. Prevention of cancers. Cancer screening and prevention are primary considerations among perimenopausal women. After 3 consecutive annual normal cervical cytology screenings in a patient at low risk, clinicians may use their own discretion to determine when another screening is necessary.33 All dysfunctional or abnormal bleeding should be evaluated in the office by endometrial sampling to rule out the presence of endometrial hyperplasia.2,35 Different professional societies have varying recommendations for mammographic screening in the fifth decade of life. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends mammography every 1 to 2 years until age 50 and yearly thereafter.33 Although women are more focused on prevention of gynecologic cancers, colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women (after lung and breast cancer).36 Clinicians need to increase patient awareness of colon cancer and colon cancer screening, especially because the incidence of this cancer increases with age.36 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends fecal occult blood testing for routine screening, and sigmoidoscopy every 3 to 5 years after the age of 50.33 Alternatively, colonoscopy can be performed at age 50 and, if the result is negative, repeated every 5 years. Over the next decade, colonoscopy, because of its superior sensitivity, may become the screening test of choice for colon cancer.37 The anchorwoman Katie Couric’s historic television broadcast of her March S36 Kaunitz 2000 colonoscopy likely raised consciousness regarding colon cancer screening among many women in the United States. Hormonal management of perimenopausal symptoms. Clinicians are becoming increasingly aware that conventional menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is not first-line therapy for perimenopausal women. Because HRT does not suppress ovulation, it does not provide contraception and will not prevent unpredictable perimenopausal bleeding. In terms of osteoporosis prevention, HRT may have a less favorable impact on femoral neck bone mineral density than OCs.38 Moreover, OCs offer several additional benefits to perimenopausal women (Table III). As discussed earlier, treatment of benign menstrual conditions is very important for perimenopausal patients, as are reduction in vasomotor symptoms, stabilization of bone mineral density with prevention of later fractures, and other noncontraceptive benefits. Women of all ages are concerned about weight gain, and 53% of those aged 35 to 45 believe that OC use causes weight gain.39 However, a pooled analysis of data from two recent double-blind, randomized, placebocontrolled clinical trials found otherwise. A total of 228 women were randomized to a triphasic triphasic norgestimate/35-µg ethinyl estradiol OC, whereas 234 received placebo for up to 6 cycles; weight gain was the same in both groups, reported by only about 2% of subjects in each group.40 Similar data from the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions trial showed that women randomized to oral conjugated equine estrogen therapy (0.625 mg/d) with or without added progestin gained 1.0 kg less on average at the end of 3 years than those assigned to placebo (P = .006).41 Nevertheless, it is a difficult task to inform women that the use of OCs or HRT will not cause excess weight gain. When should a perimenopausal woman receiving OCs be transitioned to HRT? Traditionally, reproductive endocrinologists have advised that levels of follicle-stimulating hormone should be measured during the pill-free interval. However, a single follicle-stimulating hormone assessment to determine menopausal status is unreliable.42-46 Furthermore, when women of this age are using OCs, follicle-stimulating hormone levels remain suppressed, not for just 1 week but for many weeks after discontinuation, making follicle-stimulating hormone testing even less predictive in this setting. A preferable approach is to continue combination OCs in healthy nonsmoking women until age 55 or older, when the probability of permanent cessation of ovulation is high. As menopause is reached, women can be transitioned from OCs to HRT, if they so choose, without any pill-free days or the need for expensive laboratory tests that are not dependable. New HRT formulations allow perimenopausal women receiving OCs transitioning to HRT to continue using the same progestin. August 2001 Am J Obstet Gynecol Conclusions For women and their clinicians, the perimenopausal transition signals a time of changing clinical emphasis and lifestyle. Because benign menstrual disorders are common in this age group, their prevention and treatment is a primary issue. Women in their 40s are more willing than younger women to focus on disease prevention and may likewise be more receptive to making the lifestyle modifications needed to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, as well as to prevent bone loss. They also are more highly motivated to participate in routine cancer screening programs. For many perimenopausal patients, OCs containing 30 to 35 µg ethinyl estradiol represent a sound choice, and studies have shown that one such formulation, triphasic norgestimate/35 µg ethinyl estradiol, regularizes dysfunctional bleeding, provides good cycle control, has a favorable impact on the lipoprotein profile, and does not cause weight gain. By educating perimenopausal patients about the contraceptive and noncontraceptive benefits of OCs, clinicians can help many more women in their 40s to initiate and remain on OCs. Such education also provides an opportunity to help women anticipate menopause and weigh the pros and cons of future HRT. REFERENCES 1. Klein NA, Soules MR. Endocrine changes of the perimenopause. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1998;41:912-20. 2. Speroff L, Glass RH, Kase G. Clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility. 6th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. p. 643-724. 3. Treloar AE, Boynton RE, Behn BG, Brown BW. Variation of the human menstrual cycle through reproductive life. Int J Fertil 1967;12:77-126. 4. Münster K, Schmidt L, Helm P. Length and variation in the menstrual cycle—a cross-sectional study from a Danish county. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1992;99:422-9. 5. Harlap S, Kost K, Forrest JD. Preventing pregnancy, protecting health: a new look at birth control choices in the United States. New York: The Alan Guttmacher Institute; 1991. p. 36-7. 6. Nachtigall LE. The symptoms of perimenopause. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1998;41:921-7. 7. Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical. Ortho 1999 annual birth control study. Raritan, NJ: Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical. 8. Peterson HB, Xia Z, Hughes JM, Wilcox LS, Tylor LR, Trussel J, et al. The risk of pregnancy after tubal sterilization: findings from the U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;174:1161-70. 9. Davis A, Wysocki S. Clinician/patient interaction: communicating the benefits and risks of oral contraceptives. Contraception 1999;59(1 suppl):39S-42S. 10. Sulak PJ. Oral contraceptives: therapeutic uses and quality-of-life benefits(case presentations). Contraception 1999;59(1 suppl):35S-8S. 11. Sulak PJ. The perimenopause: a critical time in a woman’s life. Int J Fertil 1996;41:85-9. 12. Schmidt-Sarosi C. Infertility in the older woman. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1998;41:940-50. 13. Henshaw SK. Unintended pregnancy in the United States. Fam Plann Perspect 1998;30:24-9,46. 14. Consensus Development Conference: diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment of osteoporosis. Am J Med 1993;94:646-50. 15. Melton LJ III. Epidemiology of osteoporosis: predicting who is at risk. Ann NY Acad Sci 1990;592:295-306. Kaunitz S37 Volume 185, Number 2 Am J Obstet Gynecol 16. Arikoski P, Komulainen J, Riikonen P, Parvianen M, Jurvelin JS, Voutilainen R, et al. Impaired development of bone mineral density during chemotherapy: a prospective analysis of 46 children newly diagnosed with cancer. J Bone Miner Res 1999;14:2002-9. 17. Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Brosnan P, Delpassand A, Zietz H, Klein MJ, Jaffe N. Osteopenia in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Med Pediatr Oncol 1999;32:272-8. 18. Rubin K. Turner syndrome and osteoporosis: mechanisms and prognosis. Pediatrics 1998;102:481-5. 19. Shargil AA. Hormone replacement therapy in perimenopausal women with a triphasic contraceptive compound: a three-year prospective study. Int J Fertil 1985;30:15-28. 20. Gambacciani M, Spinetti A, Cappagli B, Taponeco F, Maffei S, Piaggesi L, et al. Hormone replacement therapy in perimenopausal women with a low dose oral contraceptive preparation: effects on bone mineral density and metabolism. Maturitas 1994;19:125-31. 21. Lindsay R, Tohme J, Kanders B. The effect of oral contraceptive use on vertebral bone mass in pre- and post-menopausal women. Contraception 1986;34:333-40. 22. Enzelberger H, Metka M, Heytmanek G, Schurz B, Kurz C, Kusztrich M. Influence of oral contraceptive use on bone density in climacteric women. Maturitas 1988;9:375-8. 23. Kleerekoper M, Brienza RS, Schultz LR, Johnson CC. Oral contraceptive use may protect against low bone mass. Arch Intern Med 1991;151:1971-6. 24. Kritz-Silverstein D, Barrett-Connor E. Bone mineral density in postmenopausal women as determined by prior oral contraceptive use. Am J Public Health 1993;83:100-2. 25. Michäelsson K, Baron JA, Farahmand BY, Persson I, Ljunghall S. Oral-contraceptive use and risk of hip fracture: a case-control study. Lancet 1999;353:1481-4. 26. Davis A, Godwin A, Lippman J, Olson W, Kafrissen M. Triphasic norgestimate-ethinyl estradiol for treating dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96:913-20. 27. Sulak P, Lippman J, Siu C, Massaro J, Godwin A. Clinical comparison of triphasic norgestimate/35 µg ethinyl estradiol and monophasic norethindrone acetate/20 µg ethinyl estradiol: cycle control, lipid effects, and user satisfaction. Contraception 1999;59:161-6. 28. Larsson G, Milsom I, Lindstedt G, Rybo G. The influence of a lowdose combined oral contraceptive on menstrual blood loss and iron status. Contraception 1992;46:327-34. 29. Milsom I, Sundell G, Andersch B. The influence of different combined oral contraceptives on the prevalence and severity of dysmenorrhea. Contraception 1990;42:497-506. 30. Nilsson L, Rybo G. Treatment of menorrhagia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1971;110:713-20. 31. Lepine LA, Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Koonin LM, Morrow B, Kieke BA, et al. Hysterectomy surveillance—United States, 19801993. In: CDC surveillance summaries, August 8, 1997. MMWR 1997;46(No. SS-4):1-15. 32. Casper RF, Dodin S, Reid RL, and Study Investigators. The effect 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. of 20 µg ethinyl estradiol/1 mg norethindrone acetate (Minestrin), a low-dose oral contraceptive, on vaginal bleeding patterns, hot flashes, and quality of life in symptomatic perimenopausal women. Menopause 1997;4:139-47. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Health maintenance for perimenopausal women. ACOG Technical Bulletin no. 210. Washington: ACOG; 1995. National Osteoporosis Foundation. Physician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Washington: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 1998. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of anovulatory bleeding. ACOG Practice Bulletin no. 14, Washington: ACOG; 2000. American Cancer Society Website. Cancer facts and figures 1999. Available at http://www.cancer.org/statistics/cff99/data/data_ leadingnewcancer.html/. Accessed July 10, 2000. Winawer SJ, Stewart ET, Zauber AG, Bond JH, Ansel H, Waye JD, et al. A comparison of colonoscopy and double-contrast barium enema for surveillance after polypectomy. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1766-72. Taechakraichana N, Limpaphayom K, Ninlagarn T, Panyakhamlerd K, Chaikittisilpa S, Dusitsin N. A randomized trial of oral contraceptive and hormone replacement therapy on bone mineral density and coronary heart disease risk factors in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:87-94. The National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health, Washington, DC. National omnibus survey of 704 women. July 1999. Redmond G, Godwin AJ, Olson W, Lippman JS. Use of placebo controls in an oral contraceptive trial: methodological issues and adverse event incidence. Contraception 1999;60:81-5. Espeland MA, Stefanick ML, Kritz-Silverstein D, Fineberg SE, Waclawiw MA, James MK, et al. Effect of postmenopausal hormone therapy on body weight and waist and hip girths. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82:1549-56. Burger HG, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, Shelley JM, Green A, Smith A, et al. The endocrinology of the menopausal transition: a cross-sectional study of a population-based sample. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995;80:3537-45. Burger HG, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, Groome N, Guthrie JR, Green A, et al. Prospectively measured levels of serum folliclestimulating hormone, estradiol, and the dimeric inhibins during the menopausal transition in a population-based cohort of women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:4025-30. Gebbie AE, Glasier A, Sweeting V. Incidence of ovulation in perimenopausal women before and during hormone replacement therapy. Contraception 1995;52:221-2. Creinin MD. Laboratory criteria for menopause in women using oral contraceptives. Fertil Steril 1996;66:101-4. Castracane VD, Gimpel T, Goldzieher JW. When is it safe to switch from oral contraceptives to hormonal replacement therapy? Contraception 1995;52:371-6.