Masks of China: Ritual and Legend - Teacher Notes

Masks of China: Ritual and Legend

Image: Ground Opera Mask, Caocao Buyi Minority, Guizhou

Source: China Museum of the Cultural Palace of Nationalities, Beijing

Developed by the China Museum of the National Palace , t his exhibition has been generously supported by the State Ethnic Affairs Commission of the People's Republic of China, the

Australian Multicultural Foundation and the Scanlon Foundation. museumvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum/education/

Teacher notes

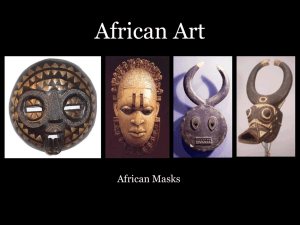

The exhibition Masks of China: Ritual and Legend offers a unique opportunity for students at all levels of schooling to view art works from the ethnic minorities of China. The masks and costumes are part of a rich tradition of mask making. While some of the objects in the exhibition are up to 200 years old, most have been collected in recent times and reflect the continuing significance of a practice which is thousands of years old.

Each mask in the exhibition has been elaborately made by hand using a wide range of materials including paper, metal, wood, cotton, bamboo and felt.

The exhibition is arranged along five key themes reflecting the typical uses of masks:

Ceremonial Dance , Opera , Weddings and Funerals , Protecting the Home and Festival and

Ritual .

Exhibition information is provided for teachers to assist preparation for students’ self guided tour of the exhibition. LOTE worksheets for beginning and advanced students of Chinese language have been prepared by the Multi Cultural Programs Unit, Student Learning Division

(DEECD).

Masks of China: Ritual and Legend is at the Immigration Museum until 24 March 2008, and materials are available online: museumvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum/education/ .

Bookings are essential for all school groups visiting the exhibition: telephone 03 9937 2754 between 8.30am and 5.00pm weekdays.

Learning in museums

Research shows that students will learn more during a visit to a museum and exhibition when they are working purposefully in small groups around the exhibits, interacting frequently with teachers and other supervisors. To make the most of an excursion to Masks of China :

• Prepare your students before the excursion; discuss the purpose and exhibition themes.

• Use the Activities provided or organise other tasks to focus students during their visit.

Please make enough copies of the selected activities for each small group to use.

• Inform all supervisors/accompanying teachers about the excursion plan and educational themes, and provide each with a copy of the Exhibition notes to assist them in guiding the students in their care.

• Follow up the excursion with group reviews and/or student-directed projects based on their experiences and research at the museum.

Curriculum links

The exhibition provides a resource for specific subject areas in primary and secondary curriculum but also offers the opportunity for rich learning tasks.

Victorian Certificate of Education (VCE)

A visit to this exhibition will provide a rich resource for the following VCE studies:

2. Drama

4. Visual Communication and Design

Victorian Essential learning Standards (VELS)

The links to curricula for Levels 1-6 VELS are outlined on the following page. museumvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum/education/ 2

Masks of China: Ritual and Legend

Level

Level 1-3

Level 4-5

Level 6

Strand

Physical , Personal and Social

Learning

Discipline Based learning

Interdisciplinary

Learning

Physical , Personal and Social

Learning

Domains

Interpersonal

Development

Humanities

The Arts

LOTE CHINESE

Intercultural knowledge and language awareness

Communication

Design, creativity and technology

Thinking

Interpersonal

Development

Civics and

Citizenship

Exhibition

Students interact with others in a shared public space viewing traditional community activities using masks and costumes.

100 Handmade masks from ethnic minorities in China.

Traditional cultural activities.

Ancient ritual performances.

Beliefs, myths and symbolism connected to masks.

Living tradition of mask making.

The exhibition provides stimulus material for discussion, writing and visual communication.

Students have the opportunity to view the collection of masks and costumes and respond in a range of forms.

Students interact with others in a shared public space viewing traditional community activities using masks and costumes. They have the opportunity to identify aspects of cultural diversity in an Asian context.

100 Handmade masks from ethnic minorities in China.

Traditional cultural activities.

Ancient ritual performances.

Beliefs, myths and symbolism connected to masks.

Living tradition of mask making. learning History

The Arts

LOTE – Chinese

Intercultural knowledge and language awareness

Learning

Physical , Personal and Social

Learning learning

Learning

Design, creativity and Technology

Thinking

Interpersonal development

Civics and

Citizenship

History

The Arts

LOTE – Chinese

Intercultural knowledge and language awareness

Design, creativity and Technology

Thinking

The exhibition provides stimulus material for discussion, writing and visual communication.

Students have the opportunity to view the collection of masks and costumes and respond in a range of forms.

Students have the opportunity to learn with others by attending an exhibition and develop knowledge and skills to allow them to take action as informed , confident members of a diverse and inclusive Australian society.

100 Handmade masks from ethnic minorities in China.

Traditional cultural activities.

Ancient ritual performances.

Beliefs, myths and symbolism connected to masks.

Living tradition of mask making.

Exploring products and performances in a cultural context.

The exhibition provides stimulus material for discussion, writing and visual communication.

Students have the opportunity to view the collection of masks and costumes and respond in a range of forms museumvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum/education/ 3

Masks of China: Ritual and Legend

Exhibition notes

The history of masks in China stretches back almost 4,000 years to when images of people wearing masks were painted on rocks along the Yangtze River. To the ancient peoples of

China masks were carriers of the soul, and a way for humans to ‘become’ non-human: animal, spirit and god.

Masks have since been developed for religious ceremonial use, protection of the home, festivals, dance and opera.

Masks of China: Ritual and Legend reveals these traditions and artistry as you discover masks from 16 ethnic groups covering five provinces and three autonomous regions.

Although these ethnic groups vary in history, beliefs, culture and geography, the use of masks in expressing ritual and legend is common to all. Through their masks, this exhibition explores the rich diversity of ethnic minorities in China.

Animal skin, fur, felt, cotton, bamboo, metal, wood and paper are transformed into beautiful, magical and dramatic masks; each expressive of the extraordinary richness of aesthetics and beliefs of the culture of China’s ethnic minorities.

China’s ethnic groups

Though ethnic minorities make up only 9% of China’s population, they live in 64% of China’s land space. The homelands of the minority peoples of China exist mostly in border areas.

China became a multiethnic state as early as the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BC). The Han people form the majority of China’s total population of over 1.3 billion, with the 55 ethnic minorities totalling over 106 million people. Across China more than 80 ethnic languages are spoken, along with 30 indigenous scripts.

1. Ceremonial dance masks

Masks are worn in religious ceremonial dances to pray for happiness and well-being. In the north of China the Shamans of Inner Mongolia wear them to communicate with gods and spirits and invoke spiritual power.

Throughout China masks are worn by the Shigongs, who are masters of many and various religious ceremonies. The Shigongs’ masks represent gods from Taoism, Buddhism and indigenous religions.

Nuo began as a religious ceremony that has since evolved into popular dance and drama.

Masks are used in Nuo ceremonial dances in the southern provinces of Guizhou, Hunan,

Sichuan and Yunnan.

Shigong dance masks of the Yao and Maonan

A Shigong is a ceremonial master of religious rituals. The Shigong may wear a mask in a dance ceremony performed to give thanks to the gods or to pray for a good harvest, and safety for people and animals. The mask the Shigong wears differs according to which deity is being prayed to.

While performing a ceremony the Shigong holds a sword or other ritual object. They may also play a musical instrument such as a drum or gong.

Shigong dance masks of the Zhuang

Many dance ceremonies are led by Shigongs, with Shigong masks representing the 36 gods of ancient folklore.

Daqiao, Zuozhai and Anlong dance ceremonies are performed outdoors to ask the gods for a reward or for rain. The indoor performances of the Qiuhua, Huanhua and Qugui dances may beseech for a child or a happy life, or to drive away disaster. museumvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum/education/ 4

Masks of China: Ritual and Legend

Shamanic masks of Inner Mongolia

A shaman has the ability to contact the spirit world through trances, and they interact with the spirit world on behalf of their community. While the shaman is a revered member of society, because of their powers some people feel uncomfortable around them.

Shamans have distinctive clothing and use ritual implements and masks. These are often inherited from a previous shaman, which increases their sanctity and power.

Qiangmu masks of Tibetan Buddhism

Qiangmu masks are hung in Tibetan Buddhist temples and are worn during the Tibetan

Buddhist Qiangmu ceremonial dance to the gods. The dance involves chanting scripture in unison with drums and copper wind instruments.

The masks represent the King, Buddha, demons, ghosts, fairies and animals. They look ferocious and terrifying to deter ghosts, demons and monsters.

Nuo masks of the Tujia and Miao

The history of Nuo drama stretches back over 3,500 years. The name is derived from an ancient ritual to drive away evil spirits where people shouted ‘nuo, nuo’. Nuo grew from this ritual into the dramatic form performed today.

Nuo masks are carved from camphor or willow wood, considered to contain spirits, and which are durable and easy to carve.

Caogai dancing masks of the Baima Tibetan

Baima Tibetan peoples living on the border of Sichuan and Gansu wear Caogai dance masks in a ceremony celebrating the lunar New Year.

They are worn to invoke the power and protection of Danashijie, the Black Bear god.

Nuo masks of the Tujia and Miao

When a performer is wearing a mask in a Nuo performance, it symbolises that the performer is possessed of a spirit. The Nuo performances, therefore, are governed by strict rules; the performers are always male – women do not touch the masks – and a performer will only speak or act in a formalised manner while wearing a mask.

Some beliefs include that after a ceremonial performance a mask becomes a living god.

2. Home protection masks

In an ancient custom a mask is hung or placed at the doorway of a house, the entrance of a temple or the gate of a village. This rich and colourful practice is still prominent in southern

China, in particular Yunnan and Guizhou.

Important masks for this purpose are the guarding gods, animal heads and Tunkou (mythical

‘swallowing animals’) that symbolise the swallowing of disaster. They avert misfortune and protect the home by driving away evil spirits.

Paintings and special utensils are also used to guard homes, villages and temples. Heavenly beasts, such as cats, adorn roofs, with at times up to seven or eight different forms of house protection employed.

Gods’ portraits

Shangyuan, Zhongyuan and Xiayuan are gods from the Taoist pantheon. Originally known as

Tang Daoyang, Ge Dingying and Zhou Huzeng, legend says they were half-brothers, sharing the one mother.

Also called Sanyan Zhanjun, the three half-brothers became great generals of an invincible army of soldiers from Heaven, Earth and Water, which won many spectacular victories.

They are respected by Shigong as the main gods for guarding the gateway to heaven, and for killing evil spirits. museumvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum/education/ 5

Masks of China: Ritual and Legend

Tunkou swallowing animal masks

The Zhuang, Yao and Shui peoples hang Tunkou masks on their doors to protect their homes.The masks represent fierce and powerful mythical animals that symbolise the swallowing of disaster. Their ferocious expressions deter evil spirits to protect the health of the family.

Temple protection masks

Tibetan peoples living on the Tibetan–Qinghai Plateau often hang masks on doors and temple gates, as well as inside the temple.

3. Opera masks

Traditional operas reflect the cultures of China’s ethnic groups, with the masks used in opera reflecting distinct regional characteristics.

The masks depict the opera characters’ gender, age and personality; among these, wise scholars, fearsome fighters, young maidens and spiritual beings. The performers’ headwear, clothing, colours and patterns also indicate the personality of the character.

Opera masks are often passed down from generation to generation, so very old masks may be in continuous use today, in this proud and popular art form.

Cuotaiji masks of the Yi

In the Yi language, Cuotaiji means an ‘era when mankind appeared’. The Cuotaiji opera consists of four sections: sacrifice, cultivation, celebration and good wishes. The sections are performed over the first two weeks of the New Year.

Six characters are acted in Cuotaiji performances, five of which wear masks of an ancient traditional design.

Nuotang opera masks of the Tujia

There are 24 types of Nuo opera. The most characteristic is the Nuotang opera of the Tujia people of Guizhou. It is performed during the Spring Festival in remote mountainous areas and is known as ‘the living fossil of the Chinese opera’.

Performers in the Nuotang opera wear vivid, lifelike wooden masks in the distinctive folk style of the local Yellow River Valley peoples.

Shigong opera masks of the Yao and Zhuang

Shigong performances were first produced as professional opera during the Qing dynasty, in the 1850s. Originally professional Shigong opera performances were known as Changshi and

Tiaoshi, after ceremonies that were part of the sacred Shigong performances.

Shigong opera tells historical folk stories in more than 300 traditional plays. The operas involve 72 different characters including gods, folk characters and historical characters.

Ground opera masks of the Buyi

Ground opera originated during the Ming dynasty, between 1368 and 1398. As the Ming dynasty expanded its territory into the southwest the soldiers brought the performance of

Ground opera with them. The Ground opera could be performed in any open space – hence its name – and was both an entertainment and military exercise.

Ground opera masks depict warriors, officers, gods, monks, clowns and animals. They are carved out of aspen wood, with painted faces. Performances are accompanied by orchestra and percussion and the stories are adapted from historical fiction such as ‘The Tang Dynasty’,

‘The Biography of Yue Fei’, and ‘Warriors of the Yang Family’.

Ground opera is performed in villages in southern China during harvest festivals and Chinese

New Year. The performing groups are made up of farmers from the same village. A Ground opera performance indicates prosperous living.

The actors cover their heads with a piece of black gauze and and wear their masks high on their foreheads. The warrior characters wear chicken feathers on their heads and small flags on their backs. museumvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum/education/ 6

Masks of China: Ritual and Legend

Tibetan opera masks

The opera of the Tibetan people is Ache lhamo , which means ‘celestial sister’, or fairy. The stories are traditionally inspired by Buddhist teachings and Tibetan history. Each performance begins with a purification of the stage and ends with a blessing ritual. Before the performers enter, the narrator sings a summary of the story.

Tibetan opera combines dance, chants, songs, and masked performances. Masks may depict humans, spirits or animals from historical stories and myths. Each mask has its own personality and emotion, which may be good and beautiful, or false, bad and ugly.

4. Wedding and funeral masks

Yi, Zhuang, Hani and Miao people all use masks in the performance of rituals at significant life stages such as birth and naming, coming of age, and weddings and funerals. These rituals facilitate a smooth transition from one stage of life to the next.

For weddings masks are worn to deter evil spirits and pray for good luck and a lasting marriage. At funerals the deceased’s face is often covered by a mask. This use reflects belief in spirits, the worship of ancestors, and cultural and spiritual understandings of life and death.

Sanyuan god

The image of Sanyuan is hung in an important place during ceremonies. Sanyuan is the principal god of the Zhuang and Yao peoples.

A Shigong will host the ceremony, and may even wear a mask depicting Sanyuan while performing a dance to express the arrival of the god.

Wedding mask of the Yi and Hani

The Yi and Hani people of Yunnan traditionally wear a bamboo mask as part of the wedding ceremony. The bamboo mask invokes the gods who will provide blessings and happiness and drive away evil spirits. Over time, the Yi people who lived near the Hani adopted this custom.

Lion dance

The Lion dance (also known as the Lion Tiger dance) is a joyous performance enjoyed across

China during festivals. The lion is considered to be a symbol of good luck, and performers mimic a lion's movements in a lion costume. The tiger represents bravery, and has the power to suppress evil.

In the dance the lion has different moods: the ‘military lion’ is powerful and brave with vigorous movements such as jumping, dropping, attacking and rolling over; the ‘gentle lion’ is docile with relaxed and steady movements such as sleeping and licking its fur.

Two people wear the lion costume, moving the head and tail separately. Sometimes, one person alone will play the part of a small lion. The Lion dance is accompanied by the loud playing of drums, gongs and cymbals.

The Yi and the Miao peoples customarily perform the Lion dance at funerals, when performers are invited by the daughter to attend her father’s burial. This dance is accompanied by gong (percussion) and cha and suona (wind instruments). The dance opens a path for the deceased person’s spirit to reach the tomb safely, and ensures blessings for the younger generation.

Festival suit of the Hani people

Hani women weave and dye their clothes according to their family tradition. Styles are diverse and the clothes show what clan the women belong to.

Clothing may be decorated with lace, pleating, embroidery and silver ornaments. Bracelets, earrings and silver necklaces are popular. The women’s costumes and hairstyles show whether or not they are married.

Anunzuo

In Yi language, Anunzuo means ‘funny face’. It refers to a mask used in the Lion Tiger dance when performed at funerals. During this dance a variety of masks are worn including a lion, a museumvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum/education/ 7

Masks of China: Ritual and Legend tiger, an old man, a monkey and Anunzuo. The masks are made of paper and brightly painted.

The inclusion of such comic figures as Anunzuo demonstrates the Yi’s philosophical attitude to death. The funeral dances have also developed into a folk activity performed purely for entertainment.

Pudan

Miao people wear the wooden Pudan mask, ‘the funny face shell’, as well as the Lion mask, when they perform the Lion dance at funerals. The Pudan mask can represent either a man

(Yepu) or a woman (Bupu).

During the Lion dance the dancers hold a handkerchief and follow the dance movement of the man on the left and the woman on the right. This type of dance is also performed for joyful festivals such as ‘Step on the Coloured Mountain’.

5. Festivals and ritual masks

Masks are worn during festivals such as the New Year, and annual sacrifices. As well as providing entertainment during these seasonal festivals, the performances celebrate the cultures and life patterns of the agricultural societies.

Ritual or sacrificial masks originated from expressions of reverence and prayer to heaven and the gods. Nowadays sacrifices and rituals that include masks are intermingled with special entertainment and acrobatic performances.

Performers wear masks of tigers, lions, farmers, and characters of the Three Kingdoms era

(the period of civil war following the Han dynasty when the leaders of the Wei, Shu and Wu kingdoms tried to unite the empire). These festivals in modern China welcome the gods, fend off disasters and usher in good luck.

Sacrificial masks in the New Year of Yi

The Yi people of Yunnan wear masks in dances celebrating the New Year. Masks of the

Shigong master and Shimu (‘the supernatural tiger and tigress’) are worn in the Tiger and

Leopard dances. Performers wear grass clothing and perform barefoot.

Before the Tiger dance, an ox is sacrificed to the spirits of heaven and earth and the mountain. The dance commemorates villagers’ ancestors and is performed to rid the village of evil and pray for good fortune.

Sacrificial masks in the Autumn Harvest time of the Tibetan and Tu

At the time of Autumn Harvest, masks are used in ceremonies in the agricultural districts of the Tu and Tibetans of east Qinghai. These areas are influenced by Nuo opera, which is incorporated into their own traditional customs.

The Autumn Harvest ceremony is called Nadon by the Tu, and Zhougelerou by Tibetans.

Both words mean ‘to be lucky and drive away evil’. Nadon dances have three parts: the

Huishou dance, mask dance and supernatural dance.

Festival masks of the Korean

The Koreans’ mask dance was once performed to entertain foreign diplomats. Later the dance was banned due to its subversive ironic content. It is now performed as a folk dance in agricultural regions.

Recreational masks in the festivals of the Zhuang, Yao, and Bai

The Spring dance (during the New Year) of the Bai people expresses wishes for a happy life.

Paper masks in the form of the white crane, red deer, monkey and Buddha, are worn. The white crane symbolises long life; the red deer is honest and docile; the monkey is clever and intelligent; and the Buddha a symbol of happiness.

People of the Zhuang and Yao perform the Lion dance, which is recorded in ancient literature and performed throughout China. The lion is a symbol of bravery and strength, which can oust evil and ensure safety and good luck. museumvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum/education/ 8